Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Finding Life Signs around Icy Moons

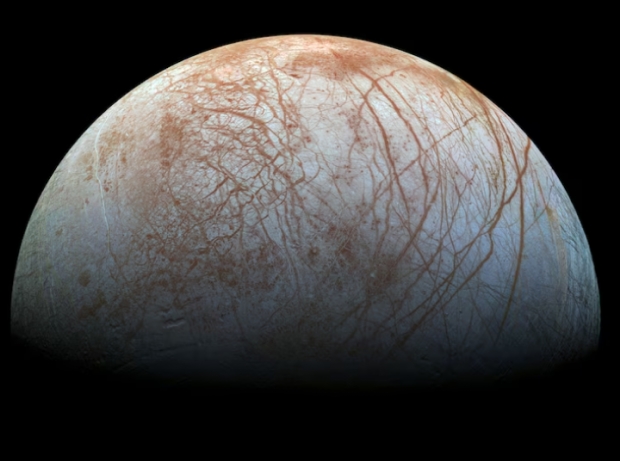

Europa Clipper is scheduled to launch on October 10, with arrival at Jupiter in 2030. That will keep subsurface oceans on our minds as we tangle with the problems of analyzing water locked under kilometers of ice. Some moons, of course, help us out. Enceladus spews watery materials into space through cracks in its crust, making flybys through its geysers a possibility for snagging samples. Europa Clipper may find further evidence of the much less dramatic plume activity that has been spotted on Europa. Clipper’s SUrface Dust Analyzer (SUDA) would prove vital in such analysis.

If cellular material is found in an ice grain snared from an orbital pass, would we be able to detect it? The answer may be found in laboratory work with a common bacteria that thrives in the waters off Alaska. As explained in new work out of the University of Washington and the Freie Universität Berlin, the bacterium Sphingopyxis alaskensis is made to order for such studies. It is smaller than Escherichia coli (frequently used in experimental work), thrives in cold conditions and needs little by way of nutrients to stay alive. If you want to approximate an icy moon’s ocean environment and experiment here with how life might operate there, Sphingopyxis alaskensis is just the ticket.

Under the direction of lead author Fabian Klenner (University of Washington), a research team has been pondering how material ejected from a moon like Enceladus might be detected by a spacecraft passing through a plume. The benefits of analyzing materials from subsurface oceans without landing are obvious, although Enceladus presents a much more benign environment for surface investigation than Europa, given the vents in its south polar crust and its much lower radiation exposure. And even if you find a way to shield a Europa lander, how to drill through all that ice?

The challenge the team has overcome is how to simulate ice grains impacting a scientific instrument at between four and six kilometers per second. The proposed solution: Fire a beam of liquid water into a vacuum. As it transforms into droplets, deploy a laser beam to excite the droplets and subject the result to mass spectral analysis, which identifies chemical and isotopic compositions. Europa Clipper’s SUrface Dust Analyzer will be able to detect ions with negative charges, even fatty acids and lipids. Thus the prospect of flying through a Europan plume looms as an exciting astrobiological possibility.

The genesis of this work comes from the authors’ analysis of Enceladus, in which they examined the evidence for phosphates in its ocean. The moon appears to contain the organic materials and the energy resources needed to support some form of life. Indeed, that work, developed in a 2023 paper, found that phosphate is present in the Enceladus ocean at levels at least 100 times higher, and perhaps much higher still, than in Earth’s oceans. Phosphates are vital to life on Earth, and this work was the first report of direct evidence of phosphorus on an icy moon. As Klenner noted then:

“By determining such high phosphate concentrations readily available in Enceladus’ ocean, we have now satisfied what is generally considered one of the strictest requirements in establishing whether celestial bodies are habitable.”

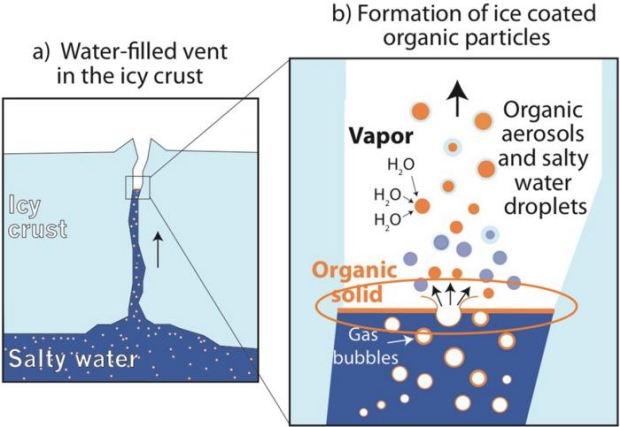

So we have an ocean laden with recently discovered dissolved phosphates, one with previously known dissolved carbonates and a variety of other carbon-containing compounds and salts. Bacterial cells found here, if encased in a liquid membrane, might well rise through cracks in the ice shell even as exposure to the vacuum would cause the waters directly below to boil. Gas bubbles bursting at the surface would allow cellular material to become incorporated into ice grains being blown outward by the plume. That’s a scenario that makes for possible life discovery.

As the paper notes:

Although an extraterrestrial biosphere might use different biochemistry, it is logical to assume an aqueous-based ecosystem with access to molecular building blocks common in our Solar System [e.g., amino acids, aliphatic hydrocarbons, sugars, nitrogen heterocycles, and others commonly found in meteorites (69)] would likely use and modify the concentrations of those molecules in ways that would deviate from an abiotic system (57, 70).

Image: The left panel shows the kilometers-thick icy crust believed to encapsulate Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Filling the crack is salty water with a proposed thin layer (shown orange) at its surface. The right panel shows that as gas bubbles rise and pop, they combine with organic material and get lofted into the spray. Credit: Postberg et al. (2018)/Nature.

The experimental results in the recent lab work on Sphingopyxis alaskensis are encouraging. The above mechanism would produce enough material in individual ice grains for cellular matter to be detected by instruments like those aboard Europa Clipper and future missions to icy moons. Indeed, a single ice grain would do the trick. Says Klenner:

“For the first time we have shown that even a tiny fraction of cellular material could be identified by a mass spectrometer onboard a spacecraft. Our results give us more confidence that using upcoming instruments, we will be able to detect lifeforms similar to those on Earth, which we increasingly believe could be present on ocean-bearing moons.”

Image: Won’t it be great when we can move past the old Galileo imagery of Europa for fresh images taken by Europa Clipper? This Galileo image shows red streaks across the surface of this smallest of Jupiter’s four large moons. New research shows that one of the instruments destined for the Clipper mission could find traces of a single cell in a single ice grain ejected from the moon’s interior. Credit: NASA/JPL/Galileo.

The paper is Klenner et al., “How to identify cell material in a single ice grain emitted from Enceladus or Europa,” Science Advances, Vol 10, Issue 12 (22 March 2024). Abstract. The paper on phosphates on Enceladus is Postberg et al., “Detection of phosphates originating from Enceladus’s ocean,” Nature 618 (14 June 2023) 489-493 (abstract).

Another Conundrum: How Long Do White Dwarfs Live?

Don’t you love the way the cosmos keeps us from getting too comfortable with our ideas? The Hubble Constant (H0), which tells us about the rate of expansion of the universe, is still a hot issue because observations from both the Hubble Space Telescope and JWST don’t tally with what the European Space Agency’s Planck mission concluded from its data on the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB).

How exactly do we fine tune the standard model of cosmology to make sense of this? The so-called Hubble Tension is hardly the only issue raised by the acquisition of new and better data, although it may be the biggest. All kinds of questions linger about what dark energy is, not to mention dark matter. Of course, challenging observations are hardly limited to cosmology. Dialing down to the stellar level, new work has emerged challenging the way white dwarf stars evolve. Contrary to all expectation, some white dwarfs seem to stop cooling, and can indeed live to a satisfying old age.

A white dwarf is what is left after a star goes through its red giant phase and sheds its outer layers. After all, most stars (over 95 percent) don’t have the mass to become a neutron star or black hole. A star like the Sun will one day enlarge, then contract, casting off its outer layers to form a planetary nebula and leaving a white dwarf behind. Planets in our inner system would likely be engulfed in the red giant phase, but get out around the asteroid belt and the chances of survival are high, with subsequent outward migration in the white dwarf period because of the star losing mass.

Sirius B is a white dwarf 8.6 light years away, and there are eight of the objects among the 100 nearest star systems. They should be cooling down because fusion no longer occurs, with the dense plasma in the star’s interior freezing so that the star solidifies from the center out. The cooling process itself can take billions of years, which is why I find these objects so appealing. They’re another example of an exotic place where planets can orbit and conceivably produce some kind of life, and recent studies have uncovered that many of them show signs of atmospheric ‘pollution,’ meaning they’ve ingested materials near them. As many as 50 percent show metals in their spectra.

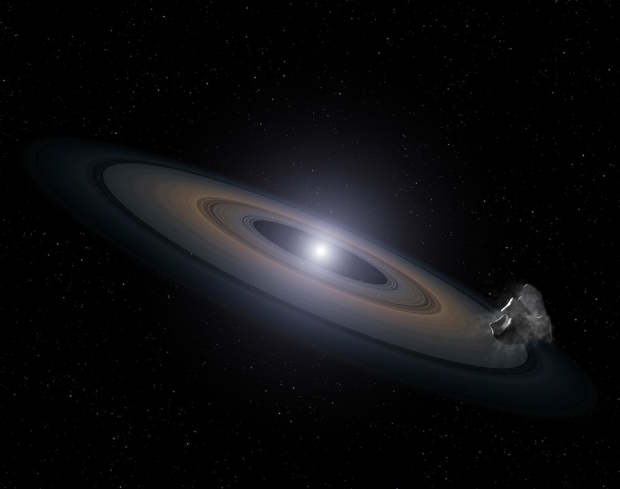

Image: This is an artist’s impression of a white dwarf (burned-out) star accreting rocky debris left behind by the star’s surviving planetary system. It was observed by Hubble in the Hyades star cluster. At lower right, an asteroid can be seen falling toward a Saturn-like disk of dust that is encircling the dead star. Infalling asteroids pollute the white dwarf’s atmosphere with silicon. These dead stars are located 150 light-years from Earth in a relatively young star cluster, Hyades, in the constellation Taurus. The star cluster is only 625 million years old. The white dwarfs are being polluted by asteroid-like debris falling onto them. Credit: NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STScI).

Finding a debris disk around a white dwarf is one thing, but planets are another matter. Only a few have so far been identified. There have been white dwarf surveys to look for surviving gas giants in such systems but their numbers are low. What we have found, though, is intriguing. WD 1856+534 b, for instance, orbits in a remarkably tight orbit and raises further questions about orbital evolution. A planetesimal designated SDSS J1228+1040 b likewise appears in a tight orbit within a white dwarf debris disk.

Because the contrast between star and planet in a white dwarf system could be as low as 1:200, according to a new paper, JWST gives us significant capabilities for imaging planets around white dwarfs. Susan Mullally (Space Telescope Science Institute) is lead author of the paper, which appears in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The researchers describe two giant planet candidates orbiting the white dwarfs WD 1202−232 and WD 2105−82. The projected separations are 11.47 and 34.6 AU respectively, and the best take on mass for each is in the range of 1 to 7 Jupiter masses. “If confirmed,” note the authors, “using common proper motion, these giant planets will represent the first directly imaged planets that are similar in age, mass, and orbital separation as the giant planets in our own solar system.”

So we’re getting there as we slowly build our exoplanet catalog around such stars. Even so, the questions seem to be multiplying because of the fact mentioned above: There is a population of white dwarfs along the so-called Q Branch of the Hertzsprung–Russell (H–R) diagram that is maintaining a constant luminosity over billions of years. This would mean there must be a source of energy inhibiting the cooling process.

Here we’re dealing with data from the Gaia satellite, cited in 2019 to announce the discovery of this population of white dwarfs. White dwarf cooling is thought to involve crystallization of core materials into a solid phase. Sihao Cheng (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton) and colleagues point to this transition in the 2019 paper:

As a liquid-to-solid phase transition in the white dwarf core, crystallization releases energy through latent heat (e.g., van Horn 1968) and phase separation (e.g., Garcia-Berro et al. 1988; Segretain et al. 1994; Isern et al. 1997), which can indeed create a cooling delay. However, the observed pile-up on the Q branch is higher and narrower than expected from the standard crystallization model (Tremblay et al. 2019, Figure 4), suggesting that there exists a cooling anomaly, i.e., an extra cooling delay in addition to crystallization.

Explaining this phenomenon is the task of a just published paper in Nature from Antoine Bédard (University of Warwick), with Cheng as a co-author. Its hypothesis is that freezing of the interior into a solid state does not produce the expected result, the solidification of the star from the inside out. Instead, crystals formed upon freezing displace heavier liquids downward, a mechanism that releases gravitational energy. This, then, would be the source of the persistent star’s energy, and would constitute, according to Bédard, “a whole new astrophysical phenomenon.” This delay in cooling could mean that we are underestimating the age of some dwarfs by billions of years.

Cheng sees the question of stellar age as central, even if we’re not sure why some white dwarfs take this path and others do not:

“One fascinating aspect of this discovery is that the physics involved is similar to something we observe in daily life: the frozen crystals within the white dwarf star float instead of sink. We might compare their behavior to ice cubes floating in water. Our work will necessitate updates to astronomy textbooks. We hope that it will also prompt astronomers to reassess the methods employed to calculate the age of stellar populations.”

It’s always satisfying to think that our textbooks will need to be updated on a regular basis, for the pace of discovery is accelerating. In this case, something as fundamental as stellar age is up for grabs. Indeed, as the Bédard and Cheng paper notes, this “population of freezing white dwarfs maintains a constant luminosity for a duration comparable with the age of the universe.” These white dwarfs, at least, fall entirely out of the category of ‘dead stars’ and force a healthy re-thinking of our assumptions.

The Mullally paper is “JWST Directly Images Giant Planet Candidates Around Two Metal-polluted White Dwarf Stars,” Astrophysical Journal Letters 962 (15 February 2020), L32 (full text). The 2019 paper discussing the cooling issues in white dwarfs is Cheng et al., “A Cooling Anomaly of High-mass White Dwarfs,” The Astrophysical Journal Vol. 886, No. 2 (25 November 2019), 100 (full text). The new paper on white dwarf cooling is Bédard et al., “Buoyant crystals halt the cooling of white dwarf stars,” Nature 627 (06 March 2024), pp. 286-288 (abstract).

Free-Floating Planets as Interstellar Targets

Just a few weeks ago I wrote about stellar interactions, taking note of a concept advanced by scientists including Ben Zuckerman and Greg Matloff that such stars would make for easier interstellar travel. After all, if a star in its rotation around the Milky Way closes to within half a light year of the Sun, it’s a more feasible destination than Alpha Centauri. Of course, you have to wait for the star to come around, and that takes time. Zuckerman (UCLA), working with Bradley Hansen, has written about the possibility that close encounters are when a civilization will attempt such voyages.

I have a further idea along the lines of motion through the galaxy and its advantages to explorers, and it’s one that may not require tens of thousands of years of waiting. We’d like to get to another star system because we’re interested in the planets there, so what if an interstellar planet nudges into nearby space? I’ll ignore Oort Cloud perturbations and the rest to focus on a ‘rogue’ or ‘free-floating’ planet as the target of a probe, and ask whether we may not already have some of these in nearby space.

After all, finding free-floating planets – and I’m now going to start calling them FFPs, because that’s what appears in scientific papers on the matter – are hard to find. There being no reflected starlight to look for, the most productive way is to pick them out by their infrared signature, which means finding them when they’re relatively young. This is what Núria Miret Roig (University of Vienna) and team did a couple of years ago, working with data from the Very Large Telescope and other sources. Lo and behold, over one hundred FFPs turned up, all of them infants and still warm.

Image: The locations of 115 potential FFPs [free-floating planets] in the direction of the Upper Scorpius and Ophiuchus constellations, highlighted with red circles. The exact number of rogue planets found by the team is between 70 and 170, depending on the age assumed for the study region. This image was created assuming an intermediate age, resulting in a number of planet candidates in between the two extremes of the study. Credit: ESO/N. Risinger (skysurvey.org).

But young FFPs are most likely to be found in star-forming regions, two of which (in Scorpius and Ophiuchus) were subjected to Miret Roig and team’s searches. What’s likely to amble along in our rather more sedate region is an FFP with enough years on it to have cooled down. The WISE survey (Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer) showed how difficult it is to pin down red dwarfs in the neighborhood, although it can be done. But even there, when you get down to L- and T-class brown dwarfs, uncertainty persists about whether you can find them. With planets the challenge is even greater.

Sometimes FFPs are found through microlensing toward the galactic core, but I don’t think we can rely on that method for finding a population of such worlds within, say, half a light year. Nonetheless, Miret Roig is not alone in pointing out that “there could be several billions of these free-floating planets roaming freely in the Milky Way without a host star.” Indeed, that number could be on the low side given what we’re learning about how these objects form. Given the excitement over ‘Oumuamua and other interstellar interlopers that may appear, I’m surprised that there hasn’t been more attention paid to how we might detect planet-sized objects near our system.

The ongoing search for Planet 9 demonstrates how difficult finding a planet outside the ecliptic can be right here at home. While pondering the best way to proceed, I’ll divert the discussion to rogue planet formation, which has always been central to the debate. Are the processes rare or common, and if the latter, do most stellar systems including our own, have the potential for ejecting planets? The last two decades of study have been productive, as we have refined our methods for modeling this process.

Recent work on the Trapezium Cluster in the Orion Nebula shows us how the catalog of FFPs is growing. The Trapezium Cluster is helpfully located out of the galactic plane, and there is a molecular cloud behind it that reduces the problems posed by field stars. I was startled to learn about this study (conducted at the European Space Agency’s ESTEC facility in the Netherlands by Samuel Pearson and Mark J McCaughrean) because of the sheer number of FFPs it turned up. Some 540 FFP candidates are identified here, ranging in mass from 0.6 to 13 Jupiter masses, although the range is an estimate based on the age of the cluster and our current models of gas giant evolution.

Image: A total of 712 individual images from the Near Infrared Camera on the James Webb Space Telescope were combined to make this composite view of the Orion Nebula and the Trapezium Cluster. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA/Science leads and image processing: M. McCaughrean, S. Pearson, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO.

What stopped me cold about this work is that among the 540 candidate FFPs, 40 are binaries. Two free-floating planets moving together without a star, and enough of them that we have to learn a new term: JuMBOs, for Jupiter-mass binary objects. How does that happen? There are even two triple systems in the data. Digging into the paper:

…we can compare their statistical properties…with higher-mass systems. The JuMBOs span the full mass range of our PMO [planetary-mass object] candidates, from 13 MJup down to 0.7 MJup. They have evenly distributed separations between ∼25–390 au, which is significantly wider than the average separation of brown dwarf-brown dwarf binaries which peaks at ∼ 4 au [42, 43]. However, as our imaging survey is only sensitive to visual binaries with separations > 25 au, we can not rule out an additional population of JuMBOs with closer orbits. For this reason we take 9% as a lower bound for the PMO multiplicity fraction. The average mass ratio of the JuMBOs is q = 0.66. While there are a significant number of roughly equal-mass JuMBOs, only 40% of them have q ≥ 0.8. This is much lower than the typical mass ratios for brown dwarfs, which very strongly favour equal masses.

That last line is interesting. Our FFP binary systems tend to have planets of distinctly different masses, which implies, according to the authors, that if the JuMBOs formed through core collapse and fragmentation – like a star – “then there must be some fundamental extra ingredient involved at these very low masses.” But the binary systems here go well below the mass where this formation method was thought to work. That opens up the ‘ejection’ hypothesis, with the planets forming in a circumstellar disk only to be ejected by gravitational interactions. So note this:

In either case, however, how pairs of young planets can be ejected simultaneously and remain bound, albeit weakly at relatively wide separations, remains quite unclear. The ensemble of PMOs and JuMBOs that we see in the Trapezium Cluster might arise from a mix of both of these “classical” scenarios, even if both have significant caveats, or perhaps a new, quite separate formation mechanism, such as a fragmentation of a star-less disk is required.

Ejection is a rational thing to look at considering that gravitational scattering is a well-studied process and may well have occurred in the early days of our own system. On the other hand, in star-forming regions like Trapezium the nascent systems are so young that this scenario may be less likely than the core-collapse model, in which the process is similar to star formation as a molecular cloud collapses and fragments. The open question is whether a scenario like this, which seems to work for brown dwarfs, is also applicable to considerably smaller FFPs in the Jupiter-mass range.

In any case, it seems unlikely that binary planets could survive ejection from a host system. As co-author Pearson puts it, “Nine percent is massively more than what you’d expect for the planetary-mass regime. You’d really struggle to explain that from a star formation perspective…. That’s really quite puzzling.”

All of which triggered a new paper from Fangyuan Yu (Shanghai Jiao Tong University) and Dong Lai (Cornell University), which takes an entirely different tack when it comes to formation of binary FFPs:

The claimed detection of a large fraction (9 percent) of JuMBOs among FFPs (Pearson & McCaughrean 2023) seems to suggest that core collapse and fragmentation (i.e. scaled-down star formation) channel plays an important role in producing FFPs down to Jupiter masses, since we do not expect the ejection channel to produce binary planets. On the other hand, (Miret-Roig et al. 2022) suggested that the observed abundance of FFPs in young star clusters significantly exceeds the core collapse model predictions, indicating that ejections of giant planets must be frequent within the first 10 Myr of a planetary system’s life.

Yu and Lai look at close stellar flybys as a contributing factor to FFP binary formation. If we’re talking about dense young star clusters, encounters between stars should be frequent, and there has been at least one study advancing the idea that bound binary planets could be the result of such flybys. Yu and Lai model two-planet systems to study the effects of a flyby on single and double-planet systems. Will an FFP result from a close flyby? A binary FFP? Or will the flyby star contribute a planet to the system it encounters?

These numerical experiments yield interesting results: The production rate of binary pairs of FFPs caused by stellar flybys is always less than 1 percent in their modeling, even when parameters are adjusted to make for tightly packed stellar systems. Directly addressing the JWST work in Trapezium and the large number of JuMBOs found there, Yu and Lai deduce that they cannot be caused by flybys, and because ejection scenarios are so unlikely, they see “a scaled-down version of star formation” at work “via fragmentation of molecular cloud cores or weakly-bound disks or pseudo-disks in the early stages of star formation.”

The matter remains unresolved, producing much fodder for future observations and debate. And while we figure out how to detect free-floating planets that may already be far closer than Proxima Centauri, we can create science fictional scenarios of journeys not just to a single rogue planet, but to a binary or even a triple system cohering despite the absence of a central star. I can only imagine how much Robert Forward, the man who gave us Rocheworld, would have enjoyed working with that.

The paper is Pearson & McCaughrean, “Jupiter Mass Binary Objects in the Trapezium Cluster” (preprint). The Miret-Roig paper is “A rich population of free-floating planets in the Upper Scorpius young stellar association,” published online at Nature Astronomy 22 December 2021 (abstract). The Fangyuan Yu & Dong Lai paper is, “Free-Floating Planets, Survivor Planets, Captured Planets and Binary Planets from Stellar Flybys,” submitted to The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

Inscribing Our Journey to Europa

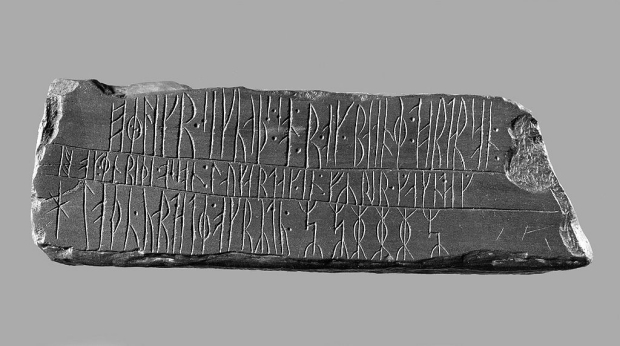

We’re a species that likes to leave evidence of itself in new places. In Greenland, for example, the Kingittorsuaq runestone, dating from the 14th Century, offers inscriptions that help chart Norse exploration of the region. The oldest inscription at New Mexico’s El Morro dates from 1605, though many explorers left their names and stories on the cliffs there. Apollo 11’s plaque, with its “We came in peace for all mankind” is justly famous, as are the Golden Records of the two Voyagers and the Pioneer plaques, even if the latter were dogged with controversy at the time of their unveiling.

Image: The Kingittorsuaq runestone. Credit: Ukendt /Nationalmuseet, Danmark, CC BY-SA 2.5 DK

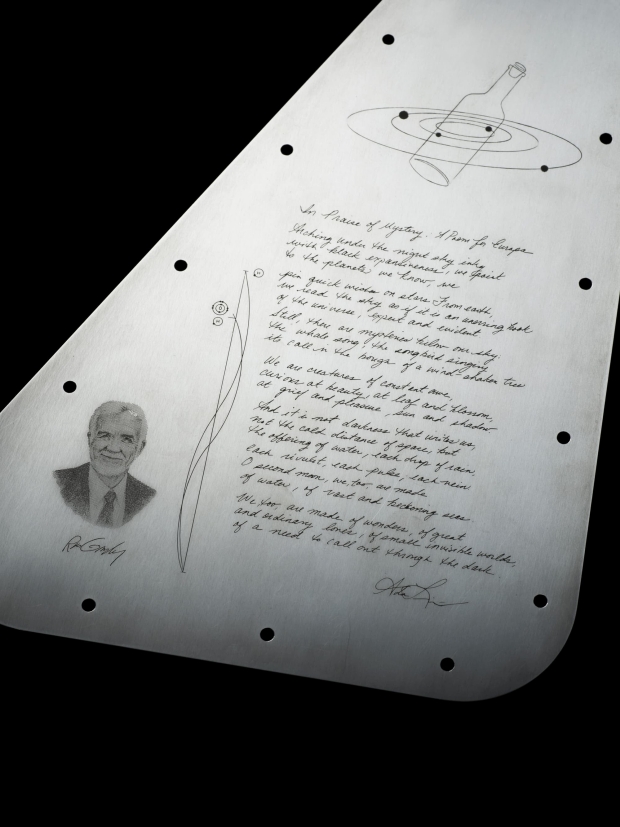

Clearly the Solar System is wide open for future plaques and markers, so that NASA’s inclusion of a plaque aboard Europa Clipper comes as no surprise. The poem it carries focuses, of course, on that intriguing moon, and I rather like poet Ada Limón’s “In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa” except for its first stanza. I snag on the word ‘expansiveness,’ and the notion of a sky inky with it. The word ‘expanse’ is itself so liminal, especially as applied to an inky night sky, that it carries its own freight of awe.

To this jaded ear, ‘expansiveness’ is bloated. I can’t imagine saying ‘the sky is certainly inky with expansiveness tonight.’ So I’ll pass on stanza 1, but go for the rest of the poem, which is a deft evocation of water’s place in our evolution and our explorations:

Arching under the night sky inky

with black expansiveness, we point

to the planets we know, we

pin quick wishes on stars. From earth,

we read the sky as if it is an unerring book

of the universe, expert and evident.

Still, there are mysteries below our sky:

the whale song, the songbird singing

its call in the bough of a wind-shaken tree.

We are creatures of constant awe,

curious at beauty, at leaf and blossom,

at grief and pleasure, sun and shadow.

And it is not darkness that unites us,

not the cold distance of space, but

the offering of water, each drop of rain,

each rivulet, each pulse, each vein.

O second moon, we, too, are made

of water, of vast and beckoning seas.

We, too, are made of wonders, of great

and ordinary loves, of small invisible worlds,

of a need to call out through the dark.

Those last three stanzas form a fine conclusion; the poem ends with a satisfying click describing its mission, which is to fly aboard Europa Clipper and wind up hurtling past the target world again and again, battered by radiation as it hunts for information about an alien sea. What a good thing it is to put human artifacts on spacecraft. There is scant likelihood, of course, that the Europa poem, flying along with a microchip containing 2.6 million names submitted by the public, will one day be read by anyone, but the impulse is to commemorate and inspire ourselves. It’s something we humans do.

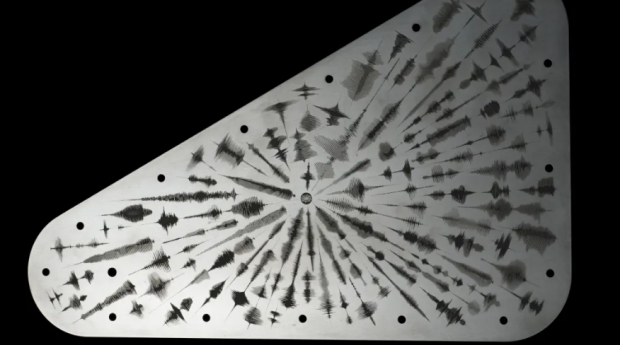

Image: The lower half of Europa Clipper’s vault plate, showing the poem by U.S. poet laureate Ada Limón (lower right), a drawing representing the Jovian system that will host the names of 2.6 million people flying with the mission on a microchip (top right), a tribute to planetary scientist Ron Greely (bottom left), and the radio emission lines known as the ‘Water Hole’ (center). Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

As a collector and user of vintage fountain pens, I am particularly pleased to see that the poem is inscribed in the author’s handwriting, a nice touch in an era increasingly learning that writing by hand, though rarely taught these days, is actually a powerful way to explore and retain ideas. The vault plate, which you can explore here, likewise contains Frank Drake’s handwriting. Drake (1930-2022), among much else in a magnificent career, contributed the first SETI search, at Green Bank in West Virginia, and the seminal Drake Equation, which estimates the probability of finding life elsewhere in the cosmos and describes the factors critical to the discussion.

Image: The upper half of Europa Clipper’s vault plate, showing the Drake Equation in Frank Drake’s own handwriting. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

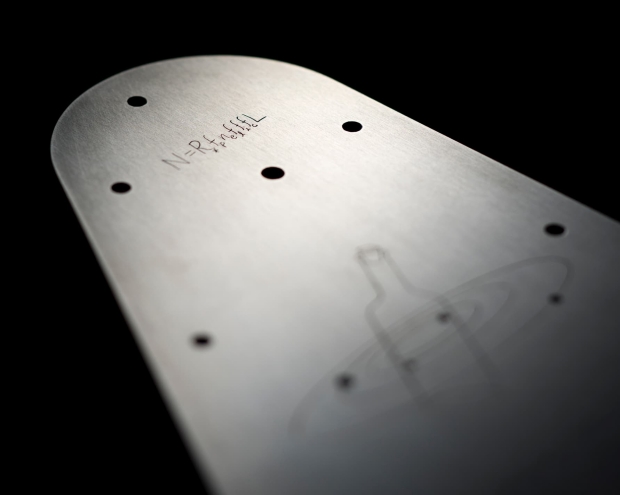

The Europa Clipper vault plate is small, measuring 1 millimeter in thickness and 18 X 28 centimeters. What I’ve described so far is the inner-facing plate. The outer side contains a visual representation of the word for ‘water’ spoken in 103 languages, with the central symbol the sign for water in American Sign Language. Water, after all, is why we are probing Europa. Audio renditions of these words are contained as visual waveforms representing each sound. They look a bit runic to me.

Image: The art on this side of the plate, which will seal an opening of the vault on NASA’s Europa Clipper, features waveforms that are visual representations of the sound waves formed by the word “water” in 103 languages. At center is a symbol representing the American Sign Language sign for “water.” Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

We’re going to get 49 close passes of Europa if all goes well when the spacecraft arrives in 2030. The commemorative plate seals an opening in the metal vault which will protect the craft’s sensitive electronics from the sleet of particles produced by interactions between the planet and its magnetic fields. We can hope to learn a good deal more about the thickness of the moon’s icy crust, its interactions with the ocean below, the composition of that ocean, and the geology of the surface. We’re getting close to Europa Clipper’s launch, slated for October at Kennedy Space Center.

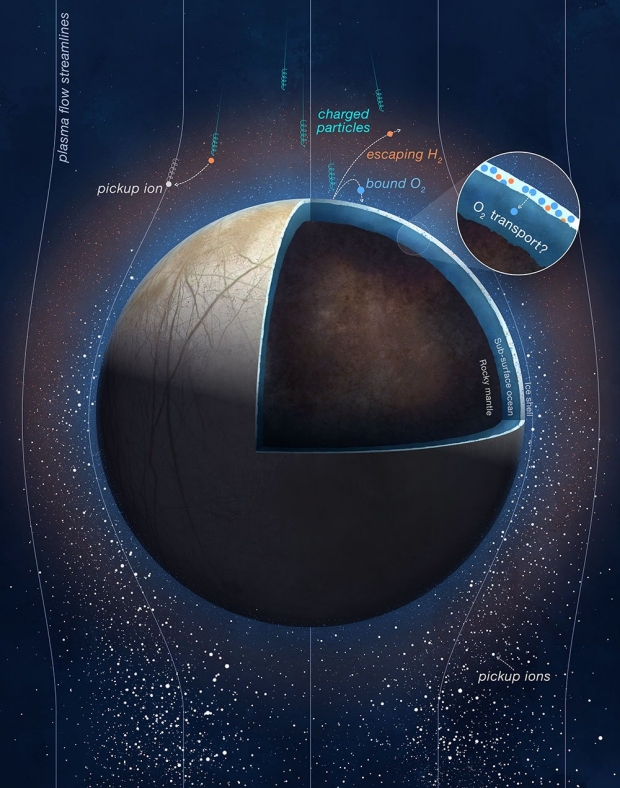

Jupiter’s radiation belts, we’ve recently learned, may play a role in what goes on in the ocean below. As a paper in Nature Astronomy explains, the bombardment of ionized particles can split any water molecules encountered on the surface, producing oxygen that could find its way into the ocean. Thus lead author Jamey Szalay (Princeton University):

“Europa is like an ice ball slowly losing its water in a flowing stream. Except, in this case, the stream is a fluid of ionized particles swept around Jupiter by its extraordinary magnetic field. When these ionized particles impact Europa, they break up the water-ice molecule by molecule on the surface to produce hydrogen and oxygen. In a way, the entire ice shell is being continuously eroded by waves of charged particles washing up upon it.”

The Juno spacecraft’s Jovian Auroral Distributions Experiment (JADE) instrument flew within 354 kilometers of the surface in September of 2022, measuring the hydrogen and oxygen ions created by the particle bombardment. The work allowed a calculation of the rate of oxygen being produced at Europa, which turns out to be about 12 kilograms per second (previous estimates have reached as high as 1000 kilograms per second). “[W]hat we didn’t realize,” adds Szalay, “is that Juno’s observations would give us such a tight constraint on the amount of oxygen produced in Europa’s icy surface.” How much of this oxygen, if any, works its way into the ocean to provide potential metabolic energy is something Europa Clipper should help us understand.

Image: This illustration shows charged particles from Jupiter impacting Europa’s surface, splitting frozen water molecules into oxygen and hydrogen molecules. Scientists believe some of these newly created oxygen gases could migrate toward the moon’s subsurface ocean, as depicted in the inset image. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SWRI/PU.

The paper is Szalay et al., “Oxygen production from dissociation of Europa’s water-ice surface,” Nature Astronomy 04 March 2024 (full text).

An Ancient ‘Quenched’ Galaxy

If individual star systems show us a wide variety of formation scenarios – and we just examined recent ESO work on circumstellar disks in different star-forming regions – the variety in galaxy evolution is even more spectacular. I’m reminded here of an unusual find when my uncle Roland died unexpectedly and I became his executor. Clearing out his house preparatory to sale, I discovered a series of astronomy photographs that he had blown up to huge scale. An image of M31, the great spiral of Andromeda, was fully six feet long and gorgeously mounted. I remembered nights as a child when he would visit from Florida and point out celestial objects for me to observe with my 3-inch reflector. M31, he told me then, was considerably wider than the Moon in the sky.

When I checked, I found that Andromeda had an angular size of 3 degrees, as opposed to about half a degree for the Moon. Even so, our spectacular sister galaxy is actually a difficult catch, with only its brighter central region visible to the naked eye, and even there tricky to find depending on local conditions of light pollution. Here I chuckle, remembering that I inherited from my uncle his eight-inch Celestron. The bane of his life was his backyard neighbor, who would power up huge outdoor security lights at the most inappropriate times. No luck seeing M31 under those conditions!

Image: M31 through a small telescope, with the Moon’s size shown for reference. Credit: Caradon Observatory.

Timothy Ferris produced a spectacular book called, simply, Galaxies, published by Random House in 1988. If you’re a deep sky devotee, it’s worth seeking out in a used book store, as it’s a coffee-table volume with spectacular photography. The following passage captures some of the grandeur verbally, though it’s from Ferris’ equally valuable Seeing in the Dark (Simon & Schuster, 2002):

The very concept of space is inadequate for dealing with galaxies; one must invoke time as well. The Andromeda galaxy is steeply inclined to our line of sight, only fifteen degrees from edge-on. Since the visible part of its disk is roughly one hundred thousand light years in diameter, the starlight reaching our eyes from its more distant side is about one hundred thousand years older than the light we simultaneously see coming from the near side. When the starlight from the far side of Andromeda started its journey, Homo habilis, the first true humans, did not yet exist. By the time the near-side light started out, they did. So within that single field of view lies a swath of time that brackets our ancestors’ origins – and that, like the incomplete dates in a biographical sketch of a living person (1944-?), inevitably raises the question of our destiny as a species. When the light leaving Andromeda tonight reaches Earth, 2.25 million years from now, who will be here to observe it? We think of Einstein’s spacetime as an abstraction, but to observe a galaxy is to sense its physical reality.

Image: An ultraviolet look at Andromeda, from NASA’s Galaxy Evolution Explorer. Credit: NASA. I owe the reminder for the Ferris quote to the blog Ten Minute Astronomy.

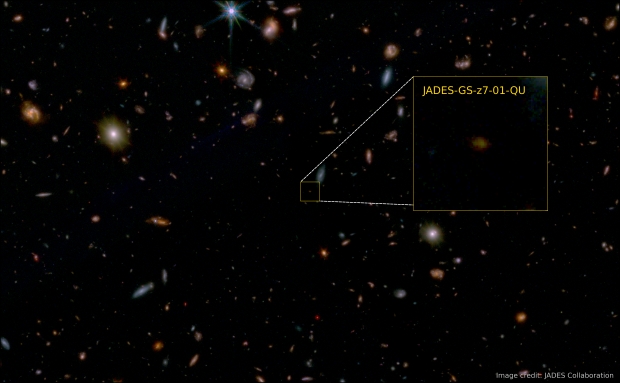

How much more stunning, then, to think about the galaxy recently observed by the team doing the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES). I will mercifully shorten its designation to JADES-GS-z7-01-QU, as the authors of the paper in Nature do. This is a so-called ‘quiescent’ galaxy, meaning that for a variety of possible reasons, star formation within it has all but ceased. The authors describe it as “a compact, discy galaxy.” And as the work of the large team led by Tobias Looser (University of Cambridge) now shows, it is also the first galaxy beyond redshift z=5 to be confirmed and characterized. Indeed, the redshift calculated for this object is z=7.3. The light from this particular galaxy would have been emitted some 13 billion years ago, a ‘mere’ 700 million years after the Big Bang.

We could also look at this galaxy in terms of its ‘comoving distance.’ The latter term is used to accommodate the fact that the universe is expanding, necessary to consider here because if an object is so far away that the light from it has traveled for most of the age of the visible universe, then during that time cosmic expansion has continued. Doing the math on this is beyond my skill set, but my research indicates that at z=7.3, the comoving distance of JADES-GS-z7-01-QU should be in the range of 30 billion light years. Mathematically inclined readers might want to fine-tune that figure.

That ‘chill up the spine’ feeling of encountering deep time/distance never quite goes away. In terms of its significance, though, we can focus in on quiescence, which is a measure of how star formation ceases in a galaxy. The galaxy in question, as observed now, has stopped forming new stars (which means it did that over 13 billion years ago). The paper indicates that the quenching period occurred 10 to 20 million years ago. Star formation seems to have been fast, ending abruptly, but what we don’t know is whether this condition is permanent. Indeed, as the paper on this work points out, how star formation is regulated in galaxies is one of the key open problems in astrophysics.

The authors run through the possibilities for slowing or stopping star formation, which include gas being expelled from galaxies by supermassive black holes or rapid star formation heating the ‘circumgalactic medium,’ thereby preventing the accretion of fresh gases. Low-mass galaxies (this is one) can be affected by feedback mechanisms that deplete the medium within galactic clusters. These differing processes operate over varying timescales, making the significance of JADES-GS-z7-01-QU clear, as noted by Roberto Maiolino (University of Cambridge), a co-author on the paper:

“We’re not sure if any of those scenarios can explain what we’ve now seen with Webb. Until now, to understand the early universe, we’ve used models based on the modern universe. But now that we can see so much further back in time, and observe that the star formation was quenched so rapidly in this galaxy, models based on the modern universe may need to be revisited.”

Image: False-colour JWST image of a small fraction of the GOODS South field, with JADES-GS-z7-01-QU highlighted. Credit: JADES Collaboration.

Thus we have the first of what should become many opportunities to learn about galaxy growth and transformation in the early universe. About the mass of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which continues to form new stars, this galaxy is dead as of the time of observation, but we can’t know what occurred in the 13 billion years before JWST was turned on it. Is quenching a widespread phenomena in the early universe, but a temporary one, so that later epochs see galactic rejuvenation? The scope of future work with JWST is beginning to take shape as we examine finds like these.

The paper is Looser et al. “A recently quenched galaxy 700 million years after the Big Bang,” Nature (06 March 2024). Abstract.

New Angles on Planet Formation

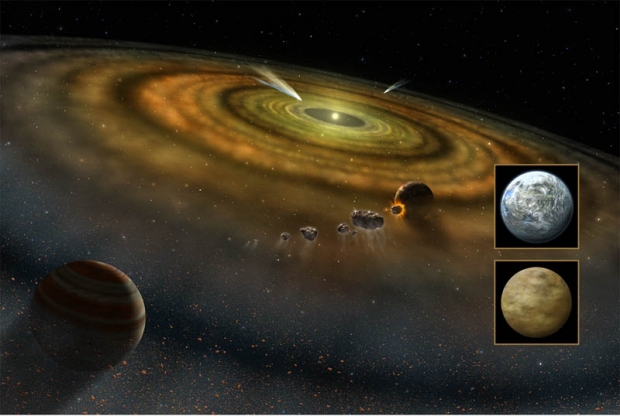

Planet formation is a fascinating subtopic of the exoplanet hunt, and it may just have produced the first exoplanet detection in data that go back as far back as 1981, though the event in question has never been confirmed as being caused by a planet. I learned this through a paper sent me recently by Jean Schneider (Observatoire de Paris), who along with colleague Danielle Briot wrote about the early days of transit searches in a chapter for the Handbook of Exoplanets (Springer, 2018).

I want to dig deeper into that chapter in a later post, but for now, I note that the planet Beta Pictoris b, discovered in 2008 and orbiting an infant star 63 light years from Earth, may have transited in 1981, according to subsequent papers on the matter. The debris disk around the primary has long fascinated astronomers and it has been investigated for the possible presence of comet-like bodies and subjected to direct imaging searches, which revealed Beta Pictoris b and confirmed it in 2009. But the 1981 data show light variations that could be interpreted as a transit.

Image: Various planet formation processes, including exocomets and other planetesimals, around Beta Pictoris, a very young type A V star. Credit: NASA/FUSE/Lynette Cook.

Testing the matter involved a nano-satellite called PicSat designed by astronomers at the Paris-Meudon observatory to look for a possible 2018 transit. Unfortunately, the mission failed when communications were lost. As Schneider and Briot write:

If the transit is confirmed in the near future, we could obtain better observations of the following transit in 2053, when the period will be known more accurately and when we could use very large and extraordinary outstanding future instruments. So, will Beta Pictoris b win the title of the first detected exoplanet?

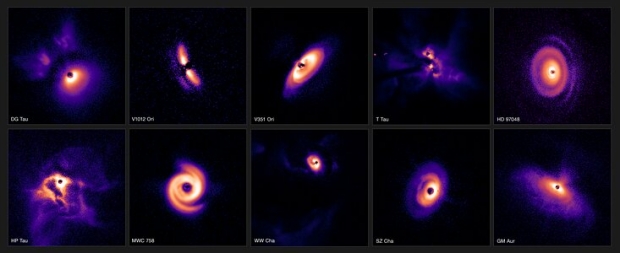

The massive debris disk at Beta Pictoris is asymmetric (likely the result of perturbations by another star), and seen edge-on from Earth. But the beauty of the circumstellar disks out of which planets form is that if we peer into planet-forming regions, we can find them oriented in all kinds of ways, as we learn in a new series of images from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope. They’re part of a survey of how planetary systems form, and they mark a transition between the intense study of individual star systems to a broad swath of planets and stars. As Christian Ginski (University of Galway, Ireland) puts it, “We’ve gone from the intense study of individual star systems to this huge overview of entire star-forming regions.”

Let’s home in on a single system to begin with to ponder how much we can learn from these disks.

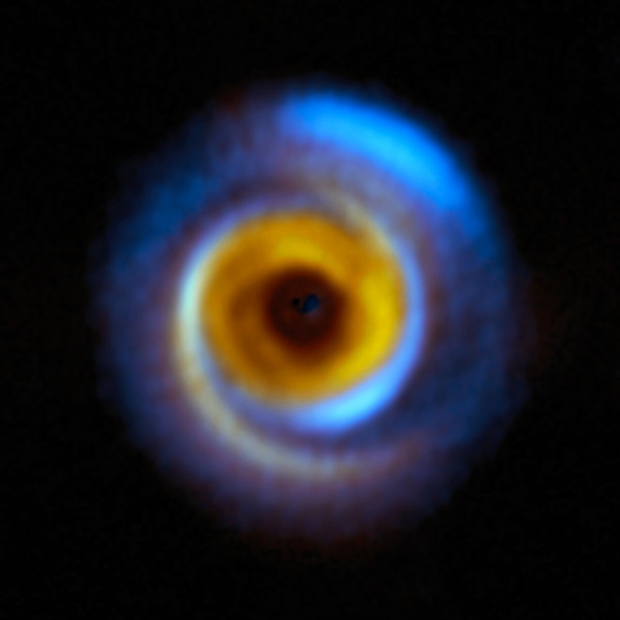

Image: This composite image shows the MWC 758 planet-forming disc, located about 500 light-years away in the Taurus region, as seen with two different facilities. The yellow colour represents infrared observations obtained with the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch (SPHERE) instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT). The blue regions on the other hand correspond to observations performed with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), in which ESO is a partner. These facilities allow astronomers to map how dust is distributed around this and other stars in different but complementary ways. SPHERE captures light from the host star that has been scattered by the dust around it, whereas ALMA registers radiation directly emitted by the dust itself. These observations combined help astronomers understand how planets may form in the dusty discs surrounding young stars. Credit: ESO/A. Garufi et al.; R. Dong et al.; ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO).

The new ESO imagery takes in numerous young stars like this one. What leaps out here is the wide range of formation scenarios. Working with the star-forming regions at Orion, Taurus and Chamaeleon I, an international team of astronomers investigated 86 stars using SPHERE, the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch instrument mounted on the VLT. The quality of the imagery is attributable to SPHERE’s adaptive optics, which allows disks to be imaged around stars down to about half the Sun’s mass while correcting for the distortions produced by looking through the Earth’s atmosphere. The use of ALMA, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, helped quantify the amount of dust in these systems.

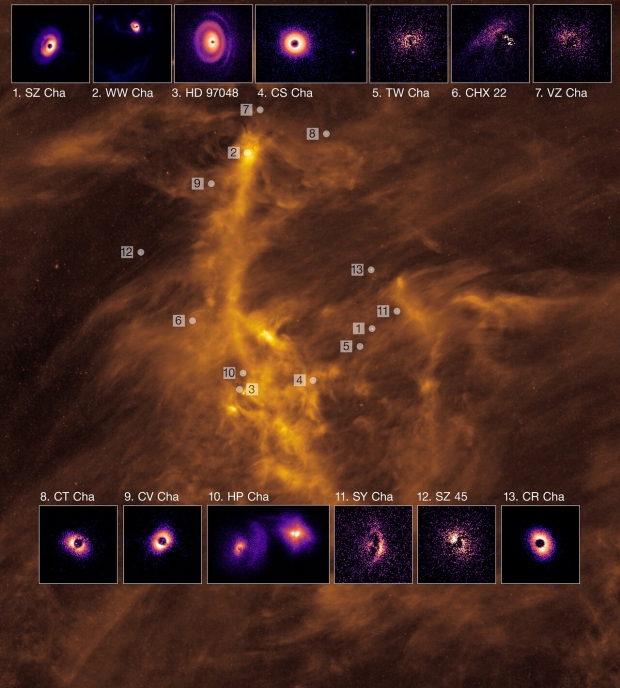

Image: This research brings together observations of more than 80 young stars that might have planets forming around them in spectacular discs. This small selection from the survey shows 10 discs from the three regions of our galaxy observed in the papers. V351 Ori and V1012 Ori are located in the most distant of the three regions, the gas-rich cloud of Orion, some 1600 light-years from Earth. DG Tau, T Tau, HP Tau, MWC758 and GM Aur are located in the Taurus region, while HD 97048, WW Cha and SZ Cha can be found in Chamaeleon I, all of which are about 600 light-years from Earth. The discs have been scaled to appear roughly the same size in this composition. Credit: ESO/C. Ginski, A. Garufi, P.-G. Valegård et al.

The imagery is stunning. Per-Gunnar Valegård (University of Amsterdam), who led the work on Orion, noted “It is almost poetic that the processes that mark the start of the journey towards forming planets and ultimately life in our own Solar System should be so beautiful.” I think we can drop that word ‘almost’ as we are reminded that the sheer wonder of celestial vistas at ever increasing scales is what drew many of us into astronomy at an early age. We’re a long way from those grainy Palomar images of Jupiter and Saturn that I acquired decades ago at Adler Planetarium in Chicago.

Image: Planet-forming discs around young stars and their location within the gas-rich cloud of Chamaeleon I, roughly 600 light-years from Earth. The team observed 20 stars in the Chamaeleon I region, detecting discs around 13. The background image shows an infrared view of Chamaeleon I captured by the Herschel Space Observatory. Credit: ESO/C. Ginski et al.; ESA/Herschel.

Meanwhile, in a separate investigation of the young star T Chamaeleontis, we gain insights into planet formation in its latter stages. Here we have the James Webb Space Telescope to thank. Naman Bajaj (University of Arizona) and Uma Gorti (SETI Institute) have been able to extract data on the four lines of the noble gases neon (Ne) and argon (Ar), with the neon detection showing processes that are occurring over an extended area. The observations show dispersing gasses from a planet-forming disk that is in its latter stages, completing the formation process. These ‘winds’ seem to be driven by stellar photons or, according to Bajaj, by the magnetic field within the disk itself.

The find is significant, says Richard Alexander (University of Leicester):

“We first used neon to study planet-forming discs more than a decade ago, testing our computational simulations against data from Spitzer, and new observations we obtained with the ESO VLT. We learned a lot, but those observations didn’t allow us to measure how much mass the discs were losing. The new JWST data are spectacular, and being able to resolve disc winds in images is something I never thought would be possible. With more observations like this still to come, JWST will enable us to understand young planetary systems as never before.”

The paper on the history of transit studies is Briot & Schneider, “Prehistory of Transit Searches,” in Handbook of Exoplanets, 2nd edition.

The papers on the SPHERE work are Ginski et al., “The SPHERE view of the Chamaeleon I star-forming region: The full census of planet-forming disks with GTO and DESTINYS programs”, Astronomy & Astrophysics (abstract).

And two other papers in the same issue: Garufi et al., “The SPHERE view of the Taurus star-forming region: The full census of planet-forming disks with GTO and DESTINYS programs,” (abstract) and Valegard et al., “Disk Evolution Study Through Imaging of Nearby Young Stars (DESTINYS): The SPHERE view of the Orion star-forming region” (abstract).

The paper on T Chamaeleontis is Bajaj et al., “JWST MIRI MRS Observations of T Cha: Discovery of a Spatially Resolved Disk Wind,” The Astronomical Journal Vol. 167, No. 3 (4 March 2024), 127 (abstract).