As we continue to investigate the parameters of the proposed FOCAL mission to the Sun’s gravitational lens, it’s worth recalling how the idea of lensing has taken hold in recent decades. Einstein noted the possibilities of such lensing as far back as 1936, but it wasn’t until 1964 that Sydney Liebes (Stanford University) worked out the mathematical theory, explaining how a galaxy between the Earth and an extremely distant object like a quasar could focus the latter’s light in ways that should be detectable by astronomers. And it wasn’t until 1979 that Von Eshleman (also at Stanford) applied the notion to using the Sun as a focusing object.

It was Eshleman who suggested sending a spacecraft to the Sun’s gravitational focus at 550 AU for the first time, where magnifications, especially at microwave frequencies like the hydrogen line at 1420 MHz, are potentially enormous. This was a year after the first ‘twin quasar’ image caused by the gravitational field of a galaxy was identified by British astronomer Dennis Walsh. Frank Drake went on to champion the uses of the Sun’s gravitational lens in a paper presented to a 1987 conference, but since then it has been Claudio Maccone who has led work on a FOCAL mission, including a formal proposal to the European Space Agency in 1993.

Lensing and Galactic Surveys

Although ESA did not have funds for FOCAL, Maccone continues to write actively about the mission in papers and books. He’ll also be fascinated to see how the subject is being discussed at the American Astronomical Society’s 217th annual meeting, which concludes today. A team led by Stuart Wyithe (University of Melbourne) has made the case in a presentation and related paper in Nature that as many as 20 percent of the most distant galaxies we can detect appear brighter than they actually are, meaning that lensing has gone from a curious effect to a significant factor in evaluating galaxy surveys to make sure they are accurate.

Rogier Windhorst (Arizona State) is a co-author of the paper that sums up this work. Windhorst uses the analogy of looking through a glass Coke bottle at a distant light and noticing how the image is distorted as it passes through the bottle. The Wyithe team now believes that gravitational lensing distorted the measurements of the flux and number density of the most distant galaxies seen in recent near-infrared surveys with the Hubble Space Telescope.

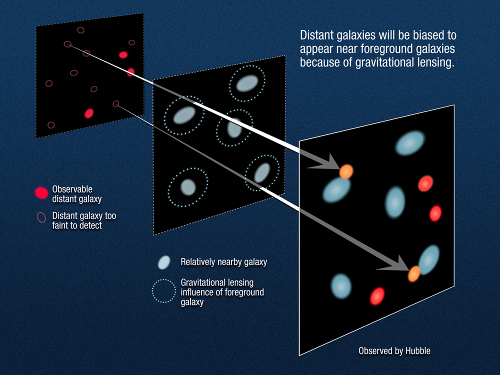

The notion makes sense when you realize that the farther and older the object under study, the more likely there will be something massive in the foreground to distort its image — after all, there is more foreground universe to look through the farther out we look. But this is the first work I know that suggests that gravitational lensing dominates the observed properties of the earliest galaxies. These are objects that, as we observe them, are between 650 million and 480 million years old, seen with Hubble at redshifts of z > 8-10 respectively. Foreground galaxies from a later era, when the universe was 3-6 billion years old, will gravitationally distort these early objects.

Image: This diagram illustrates how gravitational lensing by foreground galaxies will influence the appearance of far more distant background galaxies. This means that as many as 20 percent of the most distant galaxies currently detected will appear brighter because their light is being amplified by the effects of foreground intense gravitational fields. The plane at far left contains background high-redshift galaxies. The middle plane contains foreground galaxies; their gravity amplifies the brightness of the background galaxies. The right plane shows how the field would look from Earth with the effects of gravitational lensing added. Distant galaxies that might otherwise be invisible appear due to lensing effects. Credit: NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI).

Windhorst doesn’t doubt that the distortions play a major role in our observations:

“We show that gravitational lensing by foreground galaxies will lead to a higher number of galaxies to be counted at redshifts z>8-10. This number may be boosted significantly, by as much as an order of magnitude. If there existed only three galaxies above the detection threshold at redshifts z>10 in the Hubble field-of-view without the presence of lensing, the bias from gravitational lensing may make as many as 10-30 of them visible in the Hubble images. In this sense, the very distant universe is like a house of mirrors that you visit at the State Fair — there may be fewer direct lines-of-sight to a very distant object, and their images may reach us more often via a gravitationally-bent path. What you see is not what you’ve got!”

On the other hand, without lensing we would not be able to study many of these objects at all, as Haojing Yan (Ohio State) notes:

“On one hand, lensing is good for us in that it enables us to detect galaxies that would otherwise be invisible; but on the other hand, we will need to correct our surveys to obtain accurate tallies… We predict that many galaxies in the most remote universe will only ever be visible to us because they are magnified in this way.”

Consequences for Future Work

This work began with images from the Hubble Ultra Deep Field survey, as Yan and colleagues sought to understand why so many of the distant galaxies in the survey seemed to be located near the line of sight to galaxies in the foreground. Statistical analysis has determined that strong gravitational lensing is the most likely explanation, and Yan’s current estimate is that as many as 20 percent of the most distant galaxies currently detected appear brighter than they actually are. But he notes that the 20 percent figure is a tentative one, adding:

“We want to make it clear that the size of the effect depends on a number of uncertain factors. If, for example, very distant galaxies are much fainter than their nearby counterparts but much more numerous, the majority of such distant galaxies that we will detect in the foreseeable future could be lensed ones.”

All of this means that future surveys will have to incorporate a gravitational lensing bias in high-redshift galaxy samples. Fortunately, the James Webb Space Telescope is on the way. With its high resolution and sensitivity at longer wavelengths, it should be able to separate out the lensing effect, untangling the images to allow further study, a task that is beyond the Hubble Wide Field Camera 3. And because surveys of the first galaxies are a major part of JWST’s mission, we have a classic case of the right instrument emerging at the right time.

We’re also going to need some interesting software upgrades. Windhorst notes the necessity of developing “…a next generation of object finding algorithms, since the current software is simply not designed to find these rare background objects behind such dense foregrounds. It’s like finding a few ‘nano-needles’ in the mother-of-all-haystacks.” Such work has obvious implications for any future space mission to exploit the Sun’s gravitational lens.

The paper is Wyithe et al., “A distortion of very-high-redshift galaxy number counts by gravitational lensing,” Nature 469 (13 January 2011), pp. 181-184 (abstract).

If our early-universe galaxy counts have been distorted, am I misguided in thinking that this has implications affecting our estimates of matter/mass in our universe as a whole, and thus on our recent conclusions about its flatness?

Could there be doubly or even triply lensed galaxies out there? In other words, galaxies that are so distant that normal lensing by a single foreground galaxy would be insufficient to bring them within view, but two foreground galaxies, say, properly spaced and aligned, would preserve and magnify the image in a chain of lensings? Would there be any way to tell whether such a galaxy was made visible to us by a long chain of lenses and not by a single lens?

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=15876&cpage=1#comment-86550

Any progress on that?

Andrew is talking about my getting a comment from Claudio Maccone on various lensing issues, as discussed in the comments to the article at the link. I’ve sent the materials on but so far haven’t had a response, but Dr. Maccone has been traveling extensively, so this isn’t surprising. As I’ve just written him about this post, maybe I’ll have something to post here soon.

Re the questions of Ron and Istvan, I’m hoping for some thoughts from some of our astronomers. I have ideas on both but some of our contributors are more knowledgeable on the details than I am by a long shot.

I first heard of a probe to the sun’s gravitational focus in a Daedalus column in the late Seventies.

Has anyone calculated the possibility of using the sun’s gravitational lens for directing a tightly focused laser beam over interstellar distances, for sailing? It seems that a laser stationed at 550 AU or beyond with optics to direct most of the power at the Einstein ring should result in a beam that can have arbitrarily small spot sizes, allowing for fairly small sails on interstellar probes and ships.

One thing that needs to be considered is diffraction losses, due to the “sparse array curse” as it pertains to (or not?) a ring-shaped aperture.

Eniac, what a fascinating idea. To my knowledge, this notion has not yet appeared in the literature.

Apparently this paper, which most of us will know of, contains a lot of relevant details on how to (and how not to) beam laser power efficiently, including consideration of the “thinned array curse”. I don’t know if it mentions gravitational lensing, probably not. Unfortunately, the paper seems paywalled, so I have not had a chance to look at it. It would definitely be a good starting point for anyone wishing to follow up on the idea and work out the optics, which could be pretty challenging.

Robert L. Forward, “Roundtrip Interstellar Travel Using Laser Pushed Lightsails,” J. Spacecraft and Rockets, Vol. 21, No. 2, Mar-Apr 1984, pp. 190.

The Forward paper is a classic — I’ve got a copy here but haven’t read it in a few years. However, there’s no discussion of gravitational lensing in it that I recall. But I second your comment re the value of the paper to anyone interested in laser beamed propulsion.

I doubt that using a laser that way can work as intended. For propulsion it’s the total quantity of photons that counts, not the magnification or focusing at the other end; that is, you want every photon from the laser to be received.

The laser emission would therefore have to be directed around the sun, either in a ring or, far more easily, just point off to one side. I don’t see that there will be any improvement in dispersion by doing this.

You could of course use a black hole or neutron star to focus the sun’s radiation toward the star ship….. well, maybe not!

Ron: You are right, we need a substantial fraction of the photons to go into the beam.

The only way you get the desired improvement in dispersion is if you shine the laser in a ring around the sun and allow the beam to be shaped by coherent interference, just as the Fresnel lenses in Forward’s paper are designed to do. One condition for that is the coherence length has to be at least of the order of a solar diameter, which I believe is not a problem, but I am not entirely sure.

There probably are enough disturbances in the form of orbiting planets, coronal mass effects, etc. to introduce phase shifts that destroy coherence around the ring. Those may be addressable by adaptive optics, but I am not sure about that, either.

The most fundamental issue is whether, given perfect phasing and coherence, a ring shaped aperture will in principle permit sending most of the power into a narrow beam. That one would need to be addressed first. It is fundamental enough to be solved on paper, but I don’t think it is trivial.

It may well be that this is a case of “The thinned array curse strikes again”. Forward is said to have coined this term in the cited paper, which is why I think the paper is so relevant.