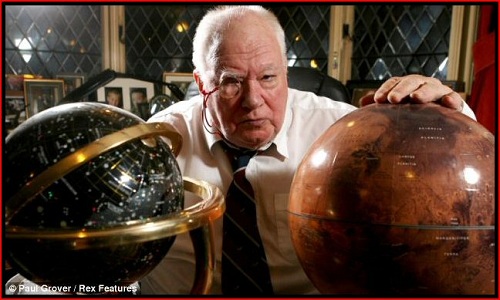

Patrick Moore, the legendary figure of British astronomy who died recently at his home in West Sussex, was deeply familiar with Ptolemy. The latter, a 2nd Century AD mathematician and astronomer, was the author of the Almagest, an astronomical treatise that presented the universe as a set of nested spheres and assumed a geocentric cosmos. Moore’s comprehensive knowledge of astronomy’s history would naturally have included the Almagest and probably Ptolemy’s astrological musings as well, but a different Ptolemy was a figure even more important to him, a cat of that name who was with him when he died. The author of 2012’s Miaow!: Cats Really are Nicer Than People! never hid his love for his feline friends.

I admire a man who, when faced with the reality that further treatments are unproductive, simply announces that he wants to go home. And go home he did, to the town of Selsey and the house called Farthings, where he died among family and friends. Moore was a man of fierce views and simple integrity whose generosity was uncommon. In a career in which he hosted the BBC show ‘The Sky at Night’ for an unprecedented 55 years, he inspired countless young people to explore the heavens. Brian May, the guitarist who published a book on astronomy with Moore, noted the latter’s devotion to his audience in a remembrance published in The Guardian.

In his private life Patrick was astoundingly giving. His dedication to young aspiring astronomers was legendary. He replied to every letter, responded to questions, helped students with gifts of equipment and the most precious gift of all – his time. He personally tutored some he thought particularly promising, and sponsored others through higher education; he gave away any income he made to the point where he had no security himself except that which his friends supplied.

‘The Sky at Night’ first appeared in 1957, and it is a remarkable fact that in the years since, Moore missed only a single episode, felled by a salmonella-laden egg in 2004. He could have gone to Cambridge and pursued an academic career, but when World War II came he lied about his age and joined Bomber Command, where he became a navigator. He called himself a ‘reluctant bachelor,’ and said that he felt the same about his fiancée Lorna in 2012 as he did in 1940, not long before she was killed by a German bomb. Love ran deep. He would never marry but would go on to parlay his extensive learning and air of eccentricity into the work of a lifetime.

The gifted amateur used a 12-inch reflector, specializing in lunar observations of a quality so high that he was chosen to be the first outside the Soviet bloc to see the results of the Luna 3 probe, showing images from the craft on the air. Moore was dealing with live TV in those days, and not all his plans worked out, as when technical problems compromised his coverage of Luna 4 transmissions, and at times his attempts to get a live telescopic view of a celestial object were ruined by cloud cover. None of this mattered and some of the glitches, such as his swallowing a fly that buzzed into his mouth, only added to the eccentric charm and reputation of the presenter. Many will remember Moore’s on-air work during the Apollo missions, which extended to later reporting on both Pioneer and Voyager. His Wikipedia article has more.

Much is being said in remembrance of Moore all over the Internet — see this obituary in The Telegraph, for example, in addition to the BBC article by Brian May that I linked to above. Moore the television presenter is remembered just as fondly as Moore the author. He began his work with Guide to the Moon in 1953 and continued for over 60 titles, much of the time working on the same 1908 Woodstock typewriter.

This morning I’ve been thumbing through the pages of his 1984 book Travellers in Space and Time, an illustrated journey through the cosmos that takes us as far as Andromeda, but I’m also thinking of titles that were older still, like The Picture History of Astronomy (1964) and Watchers of the Stars (1974). Books like these and Moore’s practical tomes on amateur astronomy brought celestial matters down to Earth, igniting enthusiasm and stoking the fires of young careers. This grand, ebullient man with the trademark monocle was indispensable, impossible to replace. “There will never be another Patrick Moore. But we were lucky enough to get one,” wrote May in his tribute. Do note that May has also set up a Patrick Moore website where members of the public he spoke to with such passion can leave their remembrances.

Sad to hear of the death of Sir Patrick Moore. A National Treasure and rewarding acquaintance who provided my reference for election as a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1990. A generous and good natured gesture from a gallant gentleman and astronomer. R.I.P.

I will miss him. 55 years? That is about as long as I have existed (I was born March 5, 1958, so conceived in early June 1957).

Patrick Moore without a doubt was one of the greatest champions of Astromony and the one who had the greatest impact on my fascination with it. When reading The Sky at Night magazine I would read the article aloud in my head to the sound of his voice – If this is a phenomena I would like to name it the Moore phenomena and Brian May said it all,

‘This grand, ebullient man with the trademark monocle was indispensable, impossible to replace. “There will never be another Patrick Moore. But we were lucky enough to get one,”

He may be gone but not his ever lasting effects on the world of Astronomy and the children who grew up with his enthusiam for a scientific field he truely loved. It will be a very long time before there will be another Great man like him.

As I have said elsewhere, I have known Patrick for longer than most, having illustrated my first book for him in 1954, and the most recent was ‘Futures: 50 Years in Space’, 2004, celebrating our 50 years of working together. I have put an obit on SF Crowsnest: http://sfcrowsnest.org.uk/sir-patrick-moore-1923-2012-obit/ and to this I would only add:

Patrick has said that when he dies “my frame can be chopped up and used for research – I shall have no further use for it.” He also said that instead of a funeral he has left ample funds for a party at his home, at which a tape will be played, in which he gives notice that he is about to do his best to blow out a candle; if he manages it, everyone will know that he is still around. Whether this will happen – I can only say, in his own famous words: “We just don’t know!”.

Sir Patrick Moore, BBC astronomy presenter, dies aged 89

by Matthew Cobb

Sir Patrick Moore, the presenter of one of the longest-running British TV shows, The Sky At Night, has died aged 89. As its name indicates, The Sky At Night is a programme about astronomy, and Moore’s indefatigable enthusiasm and knowledge inspired generations of astronomers, both amateur and professional. Amazingly, Moore had been presenting the programme with his astonishing cut-glass accent for over half a century!

The Daily Telegraph says:

“Sir Patrick reckoned that he was the only person to have met the first man to fly, Orville Wright, the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, and the first man on the moon, Neil Armstrong. He outlived them all.”

In a mail to Jerry, reader Pyers rightly summed up Moore’s influence:

To be honest, with the possible exception of David Attenborough, I can think of nobody who was instrumental in getting kids (of all ages) interested in science. Just to demonstrate the esteem he was held him, he was knighted and given one of the rarest of rare accolades: an Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Society.

Full article and videos here:

http://whyevolutionistrue.wordpress.com/2012/12/09/sir-patrick-moore-bbc-astronomy-presenter-dies-aged-89/

An article on Moore written just last January:

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2012/01/crusty-ole-sir-patrick-moore.html

When he told his mother about swallowing the fly her only comment was:

“oh, the poor thing”

Dear all,

I had the honour of meeting Patrick several times. I also visited him at his home last year. He was a generous soul and it was an inspiration to spend time in his company. Not a lot of people know, but he even wrote some science fiction books which were recently rereleased. I have them somewhere. His attendance at astronomy events and the AN February Starfest in London was always electric and people loved to see him.

Patrick also endorsed the bid of Icarus Interstellar to win 100YSS. Something I arranged when I was Vice President. Les Sheperd did the same, a few months before he died.

It’s a big loss for Britain but also for the world. We lose these amazing pioneers, but the work they started does not finish, the baton passes to the rest of us.

Dare we do better?

Kelvin F. Long

May Brian May take over Patrick Moore’s spot?

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2012/12/brian-may-to-host-moores-sky-at-night.html

Patrick became a generous and charming portrait sitter for me; his hospitality in accommodating study sessions at Farthings proved an on-going delight to me and on one memorable occasion my family too where he signed books we brought along, even gifting a Japanese translation of one of his publications to our daughter.

Sadly he never saw two compeleted portraits – oil on canvas and coloured pencil – he asked to see at our next sitting sheduled last year. Fortunately numerous photographic study sessions at Farthings have ‘bequeathed’ so many visual references that I shall work from in further celebration of Patrick’s loveable sparkling presence.

We will for ever treasure Patrick’s humour and supreme knowledge of earth’s ‘dusty widdow’ whose eye will no doubt smile eternally down on him from above as one of our greatest national treasures.

PS, I trust the large easil Patrick allowed me to leave in residence at Farthings for furture study sessions will eventually find its way back to me in Ringmer please?

Don Faulkner

Sir Patrick Moore was a fantastic man, and much loved in Selsey.

As myself a Selsey Resident, what i would like to see is a bust or statue put up in Selsey Town, please please please, we owe it to the man, he was genuis !

P.S. Will his home become a musuem?