Les Shepherd’s 1952 paper “Interstellar Flight” appears in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society,” a fitting place given Shepherd’s active involvement in the organization. He would, in fact, serve the BIS as its chairman, first succeeding Arthur C. Clarke in that role in 1954, and returning in 1957 and again in 1965 for later terms of office. “Interstellar Flight” is one of those papers that turns people in new directions after they have read it, and we can see the gradual acceptance of travel between the stars as a possibility that does not violate the laws of physics beginning in its pages.

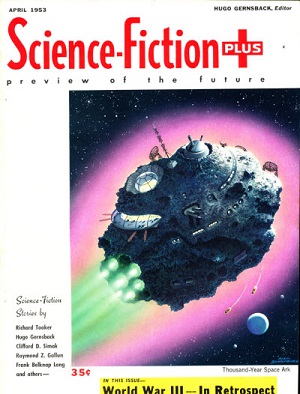

Much less heralded but more widely seen was an adapted version of “Interstellar Flight” that appeared in Science Fiction Plus in April of 1953. The magazine was a revival of Hugo Gernsback’s career as a science fiction publisher that ran for seven issues before its demise in December of the same year. Gernsback’s name was revered in science fiction circles as the founder of Amazing Stories in 1926, and for his later career with Science Wonder Stories and Air Wonder Stories, magazines he would eventually merge before selling his interest entirely in 1936. In contrast to these earlier titles, Science Fiction Plus was printed on slick paper and featured glossy covers, though many of the writers Gernsback used had worked with him in the Amazing Stories days.

Science Fiction Plus was an interesting venue for Shepherd because it exposed his work to an audience that had already encountered science fiction treatments of interstellar concepts like the generation ships he wrote about in the following paragraph:

At first sight the idea of advancing mankind’s frontiers to points requiring hundreds or even thousands of years to reach, might seem hopeless. It cannot indeed be regarded as a particularly satisfactory picture of interstellar exploration. However, regarded in terms of geological eras, centuries or millennia are small intervals, and provided that human life can be sustained in exploring vehicles for long periods, there is no reason why interstellar expansion should not proceed on this basis.

I can envision the Gernsback audience soaking this up, familiar as many of these readers would have been with stories like Robert Heinlein’s “Universe” and Don Wilcox’s “The Voyage that Lasted 600 Years.” The latter, which appeared in Amazing Stories in October of 1940, tells the tale of one Gregory Grimstone, who spends an interstellar voyage in a state of hibernation, but is wakened once every hundred years as the ‘Keeper of Traditions,’ the one contact the crew still has with the Earth left behind many generations before. Here we have the same theme of lost knowledge and a crew gradually losing the meaning of their journey that we find in Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky and a variety of later tales.

Image: Pioneering physicist Les Shepherd, whose work on interstellar flight has influenced generations of subsequent researchers.

The magnitude of the journey in terms of space and particularly time is well captured in Shepherd’s essay:

The author is not competent to deal with the biological problems of life on an interstellar vehicle undertaking a voyage lasting for a millennium. Obviously they would assume a magnitude quite as great as the engineering problems involved. In the normal way, some thirty generations would be born and would die upon the ship. It would be as though the vessel had set out for its destination under the command of King Canute and arrived with President Truman in control. The original crew would be legendary figures in the minds of those who finally came to the new world. Between them would lie the drama of perhaps ten thousand souls who had been born and had lived and died in an alien world without knowing a natural home.

Now, as to those italics. They’re clearly Gernsback’s, a suspicion natural to anyone familiar with his editorial style. The JBIS paper containing the identical passage has no italics at this point, and it’s clear that Gernsback wanted to drive home the science fictional ‘sense of wonder’ of Shepherd’s remarks with his typesetting. I’m not sure the audience needed the hint. I still find the idea of multiple generations living and dying aboard an interstellar craft to be mind-boggling even when presented in the lean text of the average scientific paper.

Shepherd would go on to discuss worldship issues ranging from population control — for humans and journeying animals — as well as the huge problem of life-support systems in a self-contained world. He saw the only feasible way to make a journey like this would be in a ship of gigantic proportions, and for him, that meant hollowing out ‘a small planetoid,’ one of perhaps a million tons (excluding the weight of propellants and fuel). He believed artificial gravity should be induced by rotating the ship, and he pondered the question of maintaining an atmosphere over the course of ten centuries. On matters of sociology, he said this:

The passage of perhaps thirty generations would pose major problems of a sociological nature. The control of population would be only one of many. Children could only be born according to some prearranged plan, since overpopulation or underpopulation would be disastrous. The community would be subjected to a degree of discipline not maintained in any existing community. This isolated group would need to preserve its civilization, and hand on precious knowledge and culture from generation to generation and even add to the store of science and art, since stagnation would probably be the first step to degradation.

I don’t want to give the impression that Shepherd’s “Interstellar Flight” is solely about worldships, because the original JBIS paper was wide in its scope, examining nuclear fission, fusion and ion propulsion and going into depth on the possibilities of antimatter. Giovanni Vulpetti has pointed out that antimatter had been little studied in terms of propulsion at the time Shepherd wrote, and it was Shepherd who brought the concept out of the realm of science fiction and into the realm of serious physics with this single paper. We owe much to “Interstellar Flight,” published a year before Eugen Sänger’s famous paper on photon rockets, and I think Shepherd was wise to let Gernsback publish a version of it that could reach a broad popular audience.

As for Gernsback, he was canny to bring a serious study of interstellar travel into the pages of his young magazine, although not as successful when it came to story selection. Science fiction historian Mike Ashley has noted a certain archaism in the fiction here because of Gernsback’s reliance on writers from the previous generation. Even so, one Science Fiction Plus story still stands out. It’s Clifford D. Simak’s “Spacebred Generations,” from the August, 1953 issue. As the title implies, this is a worldship story that flows naturally out of Shepherd’s own speculations. We’ll take a closer look at what Simak has to say in an upcoming post.

Les Shepherd’s original paper on interstellar propulsion is “Interstellar Flight,” JBIS, Vol. 11, 149-167, July 1952, from which the article in Science Fiction Plus was adapted.

We should bear in mind that population control of humans was possible even when Shepherd’s JBIS paper was written, but the advent of the contraceptive pill (late 1950’s/early 1960’s) would make birth control much more reliable. If Europe or Japan was a starship, the problem would be too few births today, not too many.

An excellent and concise article on a very important subject for manned interstellar travel, Paul. Shepherd was a far-thinking man and I am happy to report that the drop probes for the Icarus Interstellar starship plan are to be named after him! See here:

http://www.icarusinterstellar.org/tribute-interstellar-pioneer-shepherd-probes/

Don Wilcox’s story is online in its entirety here:

http://amazingstoriesmag.com/articles/voyage-lasted-600-years/

“Voyage” is certainly dated in many ways, but it is also an enjoyable story, makes some very prescient points about Worldships, and you can see where many of the future SF stories on this aspect of the genre got their start from.

An excellent discussion on Simak’s story “Spacebred Generations” along with pieces on other multigenerational starship stories mentioned above may be found here:

http://silk4calde.blogspot.com/2010/07/generation-starship-stories-clifford-d.html

A very useful list of novels and short stories on generation ships is here:

http://sciencefictionruminations.wordpress.com/science-fiction-book-reviews-by-author/list-of-generation-ship-novels-and-short-stories/

And an online paper in PDF format on the subject here:

“Theater of Memory against a Background of Stars: A Generation Starship Concept between Fiction and Reality”

by Simone Caroti

http://www.astrosociology.org/Library/PDF/Caroti_SPESIF2009.pdf

Appropriately, Russian rocket pioneer Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was one of the first to come up with the idea of the Worldship as how humans might spread across the Milky Way galaxy back in 1928.

That list of multigenerational starship stories came from a book by Simone Caroti which is discussed here:

Book Review: The Generation Starship in Science Fiction, A Critical History, 1934-2001

http://bibliorex.wordpress.com/2011/09/09/book-review-the-generation-starship-in-science-fiction-a-critical-history-1934-2001-by-simone-caroti/

Caroti also wrote a paper comparing the 1956 science fiction film classic Forbidden Planet with the William Shakespeare play it is based on, The Tempest. The paper is online here:

http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1214&context=clcweb

This is a remarkable work I wasn’t aware of. It has so many concepts that have been iterated upon in later studies, papers and books (both scientifically oriented or sci/fi).

What I find the most remarkable, is the participation of Hugo Gernsback on its publication, which is usually associated with the most starry eyed type of science fiction from the Pulps generation, which usually assume wild breakthroughs have happened, making interstellar travel almost trivial and allowing the stories to happen and bring that ‘sense of wonder’ to the reader.

I just can imagine the reaction of Gernsback and his previous Magazine’s readers to this atypical article: interstellar travel, based only on known physics and science, won’t be an easy enterprise as depicted in the stories.

Maybe the potential human drama of an actual mission like that would fit the mood of some of Gernsback’s magazine’s stories. But the cognitive dissonance between the regular Pulps Space Opera, where space travel seems easy, and this realistic description of actual interstellar travel would be stark, maybe strongly disappointing.

All Aboard the 100-Year Starship

By Mae Jemison | June 11, 2014 |

In 2012, I asked LeVar Burton (who comandeered the Scientific American website as guest editor on Wednesday) if he would join me on a trip across time and space, to another star. Then I explained, yes, really. I had a team with a modest seed-funded grant from DARPA to build an organization to ensure the radical leaps in knowledge, technology and human systems needed for people to travel beyond our solar system within the next 100 years.

Knowing that I would totally get it (being the first person to appear on Star Trek that had actually traveled in space) LeVar commented, “Mae, you all are building the Federation!” and graciously said yes. We were honored when he agreed to be on the 100 Year Starship (100YSS) Advisory Board. Yet that “Federation” comment, while a bit daunting, was extremely insightful and to the point. Here’s why.

Full article here:

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/2014/06/11/all-aboard-the-100-year-starship/

To quote:

“In fact, it might be argued that the reason there is no human presence on the moon today is because there has, in a very essential way, been a lack of broad-based public support, understanding, willingness and, perhaps most importantly of all, inclusion. And this also extends to Mars, as we know its address as well.

“Competing economic interests may play a role, but given the amount of money necessary to achieve such an undertaking, the cost-factor is actually nominal, even incidental*. Rather, the perceived “exclusivity of space” made much of the public feel space exploration would not benefit them or their children, and in fact, would leave them at a disadvantage. So instead, the public settled for movies that included them in the form of characters, adrenalin, adventure and do-gooding quests. People never lost their fascination; they were just left out.”

Gernsback’s influence is seen in the cutaway view of the asteroid starship which features “gravity generators” – Gernsback’s Big Idea from his early SF days was gravity-control via some kind of electromagnetic effect. He kept promoting the concept long after its pseudo-physics justification went away.

I feel that a worldship is at once a very romantic and a very impractical idea. Far better would be to send DNA and use the resources at the destination to reinstate humanity and culture and the mission goals.

On a practical level, Biospheres 1 and 2 have not been resounding successes (to put it gently). If we are serious about sending a living, breathing community of humans to a distant star system, the least we can do is get the concept working here on Earth under appropriate test conditions for meaningful durations.

In the Joachim Boaz list is there a definition of just what a ‘Generation Ship’ is?

Because in Tau Zero the Leonora Christine is not that, tho as someone pointed out a baby is born. Still that story was based on the old Big Crunch and the oscillatory Universe, which was only one variant on the Big Crunch.

Also it should be pointed in Blish’s Cities in Flight there was no need for generation to generation since nobody died due to the Anti-agathic drugs. Even tho planets do get colonized , the Okie cities are really nomads with no real destinations, but plenty of adventures!

So does one need a destination for a generation ship? I don’t know … in Alexei Panshin ‘s Rite of Passage the Generation Ships visit colony worlds , but seem also nomads, never intent on doing anything but plying interstellar space.

Since I have not read most of the novels on the list I don’t how many other stories there are about ‘nomad’ generational ships.

Off the top of my head, there was an episode of Star Trek Voyager where the Federation starship crew encountered the Varro, who were 400 years into living on their multigenerational vessel.

Their species is very xenophobic and avoid other beings. It also turns out there is an underground movement among the Varro to stop endlessly journeying through the galaxy and settle on a world.

The episode details here:

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/The_Disease_(episode)

A list of multigenerational ships from the Star Trek series:

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/Generational_ship

They forgot to mention Yonada, the hollowed-out planetoid made by the Fabrini to escape their exploding sun:

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/Yonada

The residents of Yonada are unaware they are on a ship and the main computer system, the Oracle, is treated like a god.

Another generation ship in Star Trek TOS:

“For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky” – hollowed out asteroid generation ship.

That is what I said, Alex, Yonada. :^)

Hi All

And the “Science Fiction +” issue is available at Archive.Org:

Science Fiction Plus, Vol. 1, No. 2

…so there you go.

Adam

Paul, according to his son Hartmut E. Sänger, Eugen Sänger’s article “Über die Grenzen der Weltraumfahrt” (Concerning the Boundaries of Spaceflight), dealing with relativistic flight mechanics and the photon rocket, was published in a journal l’Astronef no.1, 29 July 1950. I’ve been trying to obtain a copy of this article, but no luck so far.

Stephen A.

Thanks, Stephen. I had a later date on that paper, but I can’t put my hands on the reference. I suspect it’s my faulty memory at play. If I can turn up a copy of the paper at some point, I’ll forward it to you.

The Painful Truth About NASA’s Warp Drive Spaceship From A Physicist

Jason Torchinsky

Today 12:00 pm

I’ll be honest — this is not the post I wanted to write. When NASA released their new renders of a hypothetical future faster-than-light spaceship, I wanted to believe that such a craft was mere decades away from reality. Then I made the mistake of asking someone much smarter than me about it.

That much smarter someone is noted physicist Sean Carroll, a theoretical cosmologist specializing in dark energy and general relativity. He’s the sort of guy who knows about this kind of faster-than-light travel and warp bubbles and all this sort of exciting stuff. He’s a scientist immersed in this world, and as such he’s not going to sugarcoat the reality of the universe as it’s currently understood just because I want to join Starfleet.

So, when I asked him for his take on just how feasible this warp-drive ship is, here’s how he responded:

http://jalopnik.com/the-painful-truth-about-nasas-warp-drive-spaceship-from-1590330763

Paul, they link to a Centauri Dreams article from 2012 on antimatter in the post above.

By the way, right now to fuel an antimatter starship – excusing whether we could get it to work or not – is estimated currently at $3.5 quadrillion dollars (USA). NASA currently gets less than $18 billion annually. Sigh.

I guess we better start building that Worldship and making sure the crew thinks it is the entire universe and turns medieval….

”Here we have the same theme of lost knowledge and a crew gradually losing the meaning of their journey that we find in Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky and a variety of later tales.”

This is just one of several non-rational rules of thought that seems to dominate the thinking about interstellar generationships .

These can only be voluntary limitations of a moral and ideologic nature , because already today it is perfectly clear that no more knowledge or meaning will be ”lost” …not when you have everything riding seven independent servers .

Even more clearly voluntary is the bias against certain areas of human genetic engineering , because already today it is perfectly clear that human cloning and several other forms of genetic engineering could have been done years ago . A starship-creew composed of ” X-men” would make it possible to build an AFORDABLE , much cheaper kind of a generationship .

How can this be outside the scope of our thoughts ?

In other areas of tecnology it is perfectly allright to base our thoughts on tecnology which is probably 50 0r 100 years into the future , like the nuclear fusion-based propulsion system in almost every generationsship .

So , why is it that we are ”tying our hands behind our back ” , much like the typical anti-hero of many Hollywood moovies ?

Free thought is still our most powerfull tool ….and cheap if you dont count the social cost .

@ljk – the link to responses by Sean Carroll to warp drive seems to invoke Clarke’s 1st law: When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

Not that Sean is elderly, and he was careful not to say it was impossible. ;D

If warp drive were possible, with suitable telescopes we could look back in time.

That blogger jumped on the fact that Carroll said warp drive was not impossible the same way a reporter once jumped on a comment by a scientist at CERN regarding quantum physics: While it is not impossible that a chair might turn into a zebra, the odds are incredibly small. The scientist was just being a good scientist but the reporter heard “there was a chance!” The same goes for the blogger, clinging to any scrap that bolsters his vaporous belief system.

No, warp drive may not be impossible, but it requires a fuel source we do not even know if it exists and technologies way past any current capabilities. No, not impossible, but not anytime soon, either.

The usual response I see to those who aren’t gushing over warp drive and actually know a thing or two about real physics by those who are not so knowledgeable is to “be more positive”. I have also seen the usual tropes about how humans once thought heavier-than-air manned flight was impossible until the Wright Brothers came along.

The difference between flying in Earth’s atmosphere with a manned machine and trying to go FTL to Alpha Centauri is that the Wright Brothers knew the physics to fly were possible and they had access to technology to make it happen.

We have no such readily available methods for interstellar warp drive and the key ingredient fuel to make it happen MAY NOT EXIST. Either that or it is very hard to get and no one really knows how to make it work in a starship. And oh yeah, antimatter may be involved, that just slightly dangerous and extremely expensive stuff.

I want to see warp drive or some kind of FTL become reality. I also want us to find alien life. But we have to obey the rules of science and one of those rules is having solid evidence. This applies both to having real physics and solid evidence for ETI, not a bunch of stories and wishful thinking.

I also do not like how warp drive distracts from more feasible interstellar propulsion methods such as Orion or Icarus or beamed sails. They may not get us to Alpha Centauri in two weeks but they can be built either now or relatively soon. Wait around for warp drive and we could probably get to the next star system by the time such a contraption is ready, if ever. Warp drive also makes the fledgling interstellar groups look like a branch of a Star Trek fan club and not serious science.

Again, I will be the first in line to say I was wrong and offer my hearty congratulations if someone figures out how to make a real, working warp drive (though I don’t think NASA is going to cut it paying one guy $50K a year to conduct the research). Then we have to ask ourselves the next important question: Are we really ready to handle humanity zipping through nearer sections of the galaxy in a matter of weeks or months?

Many people seem to want the galaxy and our methods for getting around in it to be like the one in Star Trek, but did you notice how many hostile aliens and dangerous anomalies exist in that universe? Suppose ETI are a lot like us: What if some of them do covet Earth, or belong to a religion with the One True God and send missionary expeditions to convert the primitive heathen humans? Or suppose we encounter an Avatar type situation with worlds containing many mineral riches and a native population that is less advanced and in the way?

Worst of all, what if all these scenarios I just listed show how parochial and clueless we are about how things really operate in the Cosmos and we encounter things we have no idea what they are or how to deal with them and where missteps could be disastrous for both parties? Maybe that is the chance we have to take, but maybe we need to learn a bit more too. Maybe the galaxy can handle or could not care less what one collection of microscopic creatures (on a galactic scale) from one world do to the microscopic creatures on another world. Or maybe if we stopped trying to put the cart before the horse and became more cosmically aware, we will achieve true maturity and come across the real means to FTL in the process.

Here are some more realistic starship propulsion methods, including the one seen in the 2009 film Avatar:

http://www.projectrho.com/public_html/rocket/realdesigns.php

More pages on the Avatar starship here:

http://nextbigfuture.com/2010/01/spaceship-technology-in-avatar-is.html

http://www.enjoyspace.com/en/editorial-cases/avatar-s-venture-star

http://james-camerons-avatar.wikia.com/wiki/Interstellar_Vehicle_Venture_Star

Sean Carroll does not look very old to me:

http://preposterousuniverse.com/

Got his Ph.D from Harvard, works at the California Institute of Technology as a theoretical physicist and cosmologist.

Check out Laurence Krauss’ book The Physics of Star Trek for a discussion of the various futuristic technologies portrayed in the series and how realistic they are.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technology_in_Star_Trek

Living In Space 5: The Structures Amidst the Stars

By Liam Ginty on June 18, 2014 in Space Settlements

Throughout this series we have explored the risks that come with living in space, the psychological challenges that our future colonists will be forced to face, and the physical threats that bar our passage to the stars. But we have not discussed arguably one of the most important aspects of orbital life: our future homes. What will these massive constructions look like? How will they function?

This week in Living In Space, we take a look at a variety of proposed Space Colonies and answer the question “How do we get to there from here?”

Full article here:

http://www.spacesafetymagazine.com/living-space-5-structures-amidst-stars/

Here’s a few facts about genetic engineering and other aspects of our own biology relevant to interstellar spaceflight . If these had been known to the 1950’s founders of generationship-mythology , I believe they would have USED them with no fears of scratching infected cultural wounds .

1. There are no known reason to belive it impossible to create a radiation-resistant variant of the human species , by adding to our existing natural DNA an INDEPENDENT better DNA-maintenance module , more-or-less borrowed from an existing radiation resistant species . Some algae with modules of this kind are actualy growing inside nuclear reactors , in conditions where a human would be toasted in 30 seconds . A human with such an addition to his DNA , would in any other way be identical to a natural human , except perhaps needing a few percent more proteins in his diet . It would not be necesarry for the added DNA maintenance module to reach the extreme capability of such algae ( 10.ooo times more than us) , improoving ourselves with a moderate factor of 100 or so would be more than enough to live in an almost unshielded generationship.

With such a creew , our generationship gains many strategic advantages . One of the less obvious are the ability to rebuild the ship completely in space into something completely different from the former configuration .

A Ship accelerated by magnetic sail could have the creew living in improvised conditions for a few months , until the materials used in the sail were rebuild into the permanent 300-year habitat , thereby making it possible to reduce weight to a fraction of any other design. The same princible could be used in deceleration : Not all the habitat would need to be decelerated , only the temporary habitat plus the equipment necesary to build a new one from local materials .

2. There are no reason to believe humans could become resistant to the lack of gravity . No existing species on earth has this abilty , and creating it from scratch is far beyond our abilities . Therefore already the ISS should have been designed as rotating double-modules .

Why is it that Pulp-Fiction in this area relates better to reality than academia?

@Ole Burde June 21, 2014 at 3:29

‘Here’s a few facts about genetic engineering and other aspects of our own biology relevant to interstellar spaceflight .

1. There are no known reason to belive it impossible to create a radiation-resistant variant of the human species , by adding to our existing natural DNA an INDEPENDENT better DNA-maintenance module , more-or-less borrowed from an existing radiation resistant species .’

Would you take the chance of alteration of your DNA or would you be ok changing someone else’s? There is a risk here that we don’t know all the potential results, I for one would not be happy with imposing it on some else.

With particle beams material can still be sent to the craft all the time, hydrogen right up to the heaviest elements. We often portray these astro-settlers as cut off, they would be anything but!

‘ 2. There are no reason to believe humans could become resistant to the lack of gravity . No existing species on earth has this abilty , and creating it from scratch is far beyond our abilities.’

There is every reason to believe that humans would adapt to weightlessness over time but what are the consequences, we develop no bones, instead we develop cartilage and are they now humans or humanoids? Once we alter ourselves we are not humans anymore but merely have become a branch in the tree of life.

”Would you take the chance of alteration of your DNA or would you be ok changing someone else’s? There is a risk here that we don’t know all the potential results, I for one would not be happy with imposing it on some else.”

Genetic engineering as we know it happens at the fertilized egg stage , and sadly my own days as a ferilized egg is long past !

In order to create radiation resistant humans , it would (like most medical advances ) be necesary to gradually climp up the evolutionary ladder . Radiation resistant snails , frogs and rats would be designed and only after many generations of these would the time come for rhesus monkeys and humans .

The real problem might be just the opposite : An efficient DNA fixing mecanism would probably prevent most kinds of cancer …our future astronaut- parents might have to wait for years in line together with million of other parents wanting only the best for their as yet unborn children !

Interesting Ole Burde, but you must consider the following.

1 Our DNA repair and maintenance mechanisms are very good and could only be improved on a little, the DOUBLE stranded DNA breaks being the real killers. The elaborate mechanisms that exist in the few bacteria that can that rely on a polyploid condition, and THAT changes how the whole cell works. True, some humans cope with two or three copies of the X chromosome, but only because we have special apparatus to condense that extra one out (making it useless for dsDNA repair). Of trisomic conditions, that for chromosome 21 is the most mild, but all tetrasomic and other trisomic autosomal ones are usually lethal. Thus adding the module you speak of requires a reworking of how our whole genome works.

2. I think you are right, and that our bodies might be easily adapted to work at zero g. Unfortunately, we have good reason to believe that it might be a much harder and deeper a problem for embryo development. One even worse than for 1. above.

Rob Henry : All good and true . Of course you are right that we couldn’t just copy-paste a very specific bacterial DNA repair mecanism into our own genome giving us thousands of times better resistance . On the other hand , some insects have about 200 times better resistance than us , and nobody seems to agree about WHY . So , at the very least , this is an important direction of research . We should remeber that evolution has not had any major direct reason to select for radiatiion resistance for a very long time , so there might exist an unexploited potential which could be achieved by simple classic selective breeding ….the first experiment I would like to see is a population of varous rodents being GRADUALY exposed to growing radiation pressure during many generations .. The results might surprise us. My general idea is , that n order to reach the stars we will have to temporarily give up some of our normal ways of thinking …Columbus would not have gotten very far without breaking every 2014-style ”human right” of his creew .

The creew of a starhip does not have to be the direct ancestor of a future population . It does not have to be human at all , it could be made of humanoid robots , but this could create many kinds of unpredictable problems . Better have a creew who is ALMOST human , modified just enough to survive , and not necesarily capable of normal reproduction . It would be somewhat sad for the creew never to have its own biological children , but millions of normal parents have prooved that adoption ( or in this case giving a normal birth to a frozen embrio brought from earth) can create happy families in most cases . The crew would also know that a non-modified version of their own children would be among the thousands of frozen embryoes in the cargo.

Michael said on June 21, 2014 at 13:25:

“Would you take the chance of alteration of your DNA or would you be ok changing someone else’s? There is a risk here that we don’t know all the potential results, I for one would not be happy with imposing it on some else.”

Considering the fortunes people already spend on plastic surgery, weight loss, muscle building, gender reassignment surgery, and so forth, I am sure if there were a real opportunity to extend life spans and allow humans to survive in all sorts of conditions, many people would jump at that opportunity.

If we do physically encounter the organic crew of an alien ship some day, the chances are they will also be modified versions of their original species designed to live in space and colonize almost any kind of world.

@ Ole Burde – Chernobyl might be the natural experiment that could test the idea of rodents adapting to radiation. There has been some work looking at rodents there.

The bank voles apparently have lived through 50 generations in the hot zone without deleterious effects. There is probably some biological insights to be learned from this.

On the other hand, the forests around Chernobyl are “not decaying properly”…

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/ist/?next=/science-nature/forests-around-chernobyl-arent-decaying-properly-180950075/

@ljk June 23, 2014 at 9:53

‘..I am sure if there were a real opportunity to extend life spans and allow humans to survive in all sorts of conditions, many people would jump at that opportunity.’

I am not saying that others would not impose it on themselves but do we have the right to impose it on others.

Would it not just be better and far easier to build radiation protection than alter the human genome, I mean it is not rocket science. Water which we need anyway is a fantastic radiation absorber, electrostatics and there is magnetic fields and my favourite particle beams etc. I am not a big fan of testing on animals if there is no requirement. And as for low gravity a burst of high G forces may be that is all that is needed, power lifters bone densities are quite higher than normal and they don’t work under that continuous loading.

@ljk – which might imply that food waste won’t decay properly in a closed ecosystem? Not good. We’d need to do that by machines which costs energy.

”Would it not just be better and far easier to build radiation protection than alter the human genome”

It might be relatively easy to build , but what about the WEIGHT of it ?

A mass-eficient starship would have to carry its radiation-protection as mostly additional weight . If you try to incorporate the protection into the general design , this wil restrain the design from using the optimal weight reduction : It would be nice to have 1 meter of wet soil under your feet and live in a spaceous garden-environment , but actually most food can be grown in lightweigt low pressure hydroponics modules with a fraction of the weight of the added soil .

Also the modified crew makes it possible rebuild the ship into a different ”mode” of operation , while the crew survives forn a longish period in a temporary habitat even more leightweight than the permanent one .

”Plan A” is , ofcourse to set out with a 3mile long starship wth a population of thousands of natural humans…that is AFTER we we finsh eradicating powerty , war , corruption and general irrational behavour patterns..

A somewhat less optimistic ”Plan B” might be a good idea …

It could make starflight possibel for a small fraction of the cost of Plan A.

Want to Colonize an Alien Planet? Send 40,000 People

By Mike Wall, Senior Writer | July 28, 2014 07:01 am ET

This story was updated at 1:00 p.m. EDT on July 28.

If humanity ever wants to colonize a planet beyond the solar system, it’s going to need a really big spaceship.

The founding population of an interstellar colony should consist of 20,000 to 40,000 people, said Cameron Smith, an anthropologist at Portland State University in Oregon. Such a large group would possess a great deal of genetic and demographic diversity, giving the settlement the best chance of survival during the long space voyage and beyond, he explained.

Full article here:

http://www.space.com/26603-interstellar-starship-colony-population-size.html

To quote:

“Do you want to just squeak by, with barely what you can get? Or do you want to go in good health?” Smith said on July 16 during a presentation with NASA’s Future In-Space Operations (FISO) working group. “I would suggest, go with something that gives you a good margin for the case of disaster.”

Revisiting the numbers

In the past, researchers have proposed that a few hundred people would be sufficient to establish a settlement on or near an alien planet. But Smith thought it was time to take another look.

“I wanted to revisit the issue,” he said. “It had been quite a long time, and of course we now know more about population genetics from genomics.”

For his study, which was published in April in the journal Acta Astronautica, Smith assumed an interstellar voyage lasting roughly 150 years. This time frame is consistent with that envisioned by researchers at Icarus Instellar, a nonprofit organization dedicated to pursuing travel to another star.

Smith’s calculations, which combine information from population genetics theory and computer modeling, point toward a founding population of 14,000 to 44,000 people. A “safe and well-considered figure” is 40,000, about 23,000 of whom would be men and women of reproductive age, Smith writes in the study.

This figure may seem “astoundingly large,” Smith acknowledged, but he stressed that it makes sense.

“This number would maintain good health over five generations despite (a) increased inbreeding resulting from a relatively small human population, (b) depressed genetic diversity due to the founder effect, (c) demographic change through time and (d) expectation of at least one severe population catastrophe over the five-generation voyage,” Smith writes in the Acta Astronautica paper.

Data from the real world support the overall thrust of his findings, Smith added.

“Almost no natural populations of vertebrates dip below around five to 7,000 individuals,” he said during the FISO talk. ” There are genetic reasons for this. And when they do go below this, sometimes they survive, but many times they go into what’s called a demographic or extinction vortex.”

Sending frozen sperm and eggs on the voyage with a limited number of human “tenders” is also an option, Smith said, though he didn’t consider it seriously in the new paper.

“It can be done, but it’s so different from the human experience of living in communities and so forth that I’ve kind of avoided that,” he said. “I’m kind of assuming, or sticking with, ‘What is the experience of humanity so far, and what can we learn from it?”

Project Persphone: British Scientists Building ‘Living Space Ark’ To Save Humanity

Huffington Post UK

Posted: 28/04/2014 09:32 BST

Updated: 28/04/2014 09:59 BST

British scientists are working on a space ark capable of sustaining humanity in the event of a global catastrophe.

Even though none of them will ever live to see it launched.

The Times reports that researchers from the universities of Greenwich, Warwick and Surrey are helping to lead the project, which is known as Project Persephone.

In all 13 scientists are involved, six British but also including team members from the USA, Italy and the Netherlands.

Full article here:

http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2014/04/28/project-persephone-space-ark_n_5224741.html

To quote:

The stated aim is to investigate “living technologies” that might help in the “context of habitable starship architecture that can respond and evolve according to the needs of its inhabitants”. The vision is for a craft capable of sustaining a few thousand individuals for multiple generations, while the ship travels to a planet able to sustain life.

The idea is for the craft to be self-sustaining, forming an ecosystem which incorporates some of the same processes seen on Earth for generating light, air, water, food and gravity, but using the best elements of modern tech too.

Key to the effort will be the development of biofuels and artificial soil.

Rachel Armstrong, a senior architecture and design lecturer at the University of Greenwich, told the Times: “it’s about challenging our notion of sustainability and looking at what the conditions are for survival and how we would take those with us.”