by Paul Gilster | Oct 24, 2017 | Deep Sky Astronomy & Telescopes |

We seem to be entering ‘new eras’ faster than I can track. Certainly the gravitational wave event GW170817 demonstrates how exciting the prospects for this new kind of astronomy are, with its discovery of a neutron star merger producing a heavy-metal seeding ‘kilonova.’ But remember, too, how early we are in the exoplanet hunt. The first exoplanets ever detected were found as recently as 1992 around the pulsar PSR B1257+12. Discoveries mushroom. We’ve gone from a few odd planets around a single pulsar to thousands of exoplanets in a mere 25 years.

We’re seeing changes that propel discovery at an extraordinarily fast pace. Look throughout the spectrum of ideas and you can also see that we’re applying artificial intelligence to huge datasets, mining not only recent but decades-old information for new insights. Today’s problem isn’t so much data acquisition as it is data storage, retrieval and analysis. For the data are there in vast numbers, soon to be augmented by huge new telescopes and space missions that will take our analysis of planetary atmospheres down from gas giants to Earth-size worlds.

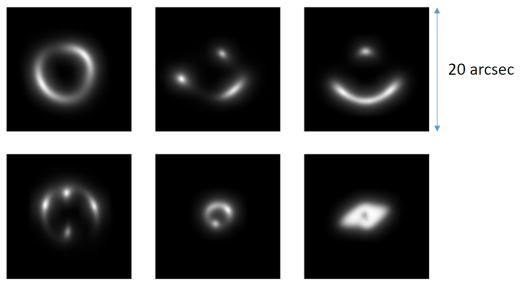

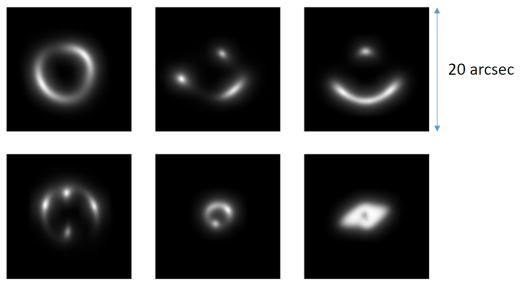

Consider what a team of European astronomers has come up with by way of gravitational lensing. Working at universities in Groningen, Naples and Bonn, the scientists have deployed artificial intelligence algorithms similar to those that have been used in the marketplace by the likes of Google, Facebook and Tesla. Feeding a neural network with astronomical data, the team was able to spot 56 new gravitational lens candidates. All of this in a field of study that normally demands sorting thousands of images and putting human volunteers to work.

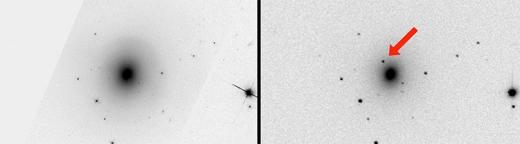

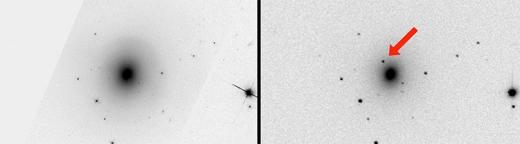

Image: With the help of artificial intelligence, astronomers discovered 56 new gravity lens candidates. This picture shows a sample of the handmade photos of gravitational lenses that the astronomers used to train their neural network. Credit and copyright: Enrico Petrillo (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen).

The team’s astronomical data were drawn from the optical Kilo Degree Survey (KiDS). Working the data is a ‘convolutional neural network’ of the kind Google’s AlphaGo used to beat Lee Sedol, the world’s best Go player. Carlo Enrico Petrillo (University of Groningen, The Netherlands) and team first fed the network millions of training images of gravitational lenses, a project that displayed the lensing properties the researchers wanted to identify.

The images from the Kilo Degree Survey cover about half of one percent of the sky. Matching the new imagery with its training images, the neural network found 761 lens candidates, which subsequent analysis by the astronomers whittled down to 56. These are all considered lensing candidates in need of confirmation by telescopes. The network rediscovered two known lenses but missed a third known lens considered too small for its training sample.

For Carlo Enrico Petrillo, the implications are clear:

“This is the first time a convolutional neural network has been used to find peculiar objects in an astronomical survey. I think it will become the norm since future astronomical surveys will produce an enormous quantity of data which will be necessary to inspect. We don’t have enough astronomers to cope with this.”

Exactly so. We’re accumulating data faster than we can analyze our material, which is why artificial intelligence advances are so telling. Training the network to recognize smaller lenses and to reject false ones is next on the team’s agenda. In the context of improving AI, bear in mind the recent major upgrade of Google’s AlphaGo to AlphaGo Zero, which defeated regular AlphaGo 100 games to 0. The new version trained itself from scratch in three days.

Image: With the help of artificial intelligence, astronomers discovered 56 new gravity lens candidates. In this picture are three of those candidates. Credit and Copyright: Carlo Enrico Petrillo (University of Groningen).

The paper is Petrillo et al., “Finding strong gravitational lenses in the Kilo Degree Survey with Convolutional Neural Networks,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Vol. 472, Issue 1 (21 November 2017), pp. 1129-1150 (abstract). On AlphaGo Zero, see Silver et al., “Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge,” Nature 550 (19 October 2017), pp. 354-359 (abstract).

by Paul Gilster | Oct 23, 2017 | Deep Sky Astronomy & Telescopes |

I had thought to go straight back into current news after Centauri Dreams‘ recent hiatus, but that’s never a fully satisfactory solution, especially when major events happen while I’m away. I don’t want to simply repeat what everyone has already read about the gravitational wave event GW170817, but there are a few things that caught my eye that we can discuss this morning. After all, we’re dealing with a new phenomenon — kilonovae — that has been predicted but never observed. Nor have we ever before tied gravitational wave events to visible light.

Image: Artist’s impression of merging neutron stars. Credit: ESO.

Now we’re seeing the combination of gravitational wave and electromagnetic astronomy in what promises to be a fertile new ground of study. The fifth GW event ever observed, GW170817 was detected on August 17 of this year by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the US, working with the Virgo Interferometer in Italy. In less than two seconds, the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and ESA’s INTErnational Gamma Ray Astrophysics Laboratory (INTEGRAL) detected a gamma ray burst from the same area of sky.

The collaborative nature of the observations that ensued is quite an achievement. What our gravitational wave detectors can give us is a broad window on the sky within which the event can be confined, one that contains millions of stars and is localized to an area of about 35 square degrees. Telescopes searching for the source included ESO’s Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA) and VLT Survey Telescope (VST) at the Paranal Observatory, the Italian Rapid Eye Mount (REM) telescope at ESO’s La Silla Observatory, the LCO 0.4-meter telescope at Las Cumbres Observatory, and the American DECam at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory. Pan-STARRS and Subaru in Hawaii quickly joined in.

I won’t keep listing them here, but about 70 observatories around the world went to work on GW170817, with the Swope 1-meter instrument in Chile announcing a new point of light close to the lenticular galaxy NGC 4993 in Hydra, quickly verified by VISTA observations in the infrared. Distance estimates agreed with the 130 million light year distance of NGC 4993, so what we have is the closest gravitational wave event yet detected and a relatively close gamma-ray burst.

Image: A map of the approximately 70 light-based observatories that detected the gravitational-wave event called GW170817. On August 17, the LIGO and Virgo detectors spotted gravitational waves from two colliding neutron stars. Light-based telescopes around the globe observed the aftermath of the collision in the hours, days, and weeks following. They helped pinpoint the location of the neutron stars and identified signs of heavy elements, such as gold, in the collision’s ejected material. Credit: LIGO-Virgo.

This is the first time I have encountered the term ‘kilonova,’ though the idea behind it is decades old. The properties of this event track theoretical predictions that have been used to explain short gamma-ray bursts, events a thousand times brighter than a typical nova. The simultaneous detection of gravitational waves and gamma rays from this source provides powerful evidence. The merger of two neutron stars, thought to be the cause of the event, has produced a burst of heavy elements moving outbound as fast as .20 c.

Each neutron star in the binary that merged weighed between 1 and 2 solar masses, making the detection of their merger tricky because they are so much smaller than the black holes events we have previously observed. Thus Eliot Quataert (UC-Berkeley):

“We were anticipating LIGO finding a neutron star merger in the coming years but to see it so nearby – for astronomers – and so bright in normal light has exceeded all of our wildest expectations. And, even more amazingly, it turns out that most of our predictions of what neutron star mergers would look like as seen by normal telescopes were right!”

Thus we expand our understanding of how heavy elements are created, a process that can happen in stellar cores through fusion up to iron. Just how elements beyond iron are produced has always been a major issue in astrophysics, but neutron star mergers offer a solution. It was evidently Quataert, working with Brian Metzger (Columbia University) and Daniel Kasen (UC-Berkeley) who applied the term ‘kilonova’ to such events in a 2010 paper (see this UC-Berkeley news release). Kasen refers to neutron star merger debris as ‘weird stuff — a mixture of precious metals and radioactive waste.’

And Columbia postdoc Jennifer Barnes, who had worked with Kasen at Berkeley, helped nail down what a kilonova should look like:

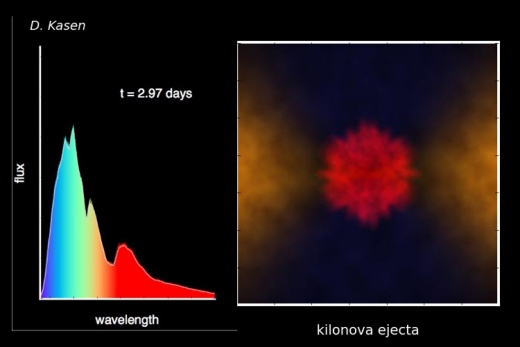

“When we calculated the opacities of the elements formed in a neutron star merger, we found a lot of variation. The lighter elements were optically similar to elements found in supernovae, but the heavier atoms were more than a hundred times more opaque than what we’re used to seeing in astrophysical explosions,” said Barnes. “If heavy elements are present in the debris from the merger, their high opacity should give kilonovae a reddish hue.”

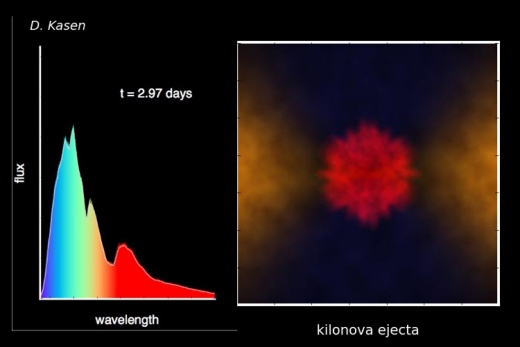

Image: A team of UC Santa Cruz astronomers led by former UC Berkeley graduate student Ryan Foley was the first to detect the light from the neutron star merger 11 hours after the gravitational waves from the collision reached Earth. The left image shows that the glow (red arrow) was not there four months earlier. Credit: UC-SC, Swopes Telescope and Hubble.

The observations fit the calculations, with the color of the merger event shading from an earlier blue to the reddish signature showing the heavier elements of the inner debris cloud.

Image: Three days after the merger and explosion, the bright blue glow from lighter elements in the outer polar regions is beginning to fade, giving way to the red glow from the heavier elements in the surrounding doughnut and spherical core. The red glow persisted for more than two weeks. Credit: Dan Kasen.

About 6 percent of a solar mass of heavy elements came out of all this, a yield of gold alone that was more than 200 Earth masses, and a platinum yield of nearly 500 Earth masses. Neutron star mergers, it appears, can account for all the gold in the visible universe. So much for the idea that what we can now call ‘ordinary’ supernovae can account for the heavy elements beyond iron. Clearly, neutron star mergers are a key player. Gravitational wave astronomy is already paying off.

Those wanting to dig into the papers on GW170817 can start with Kasen et al., “Origin of the heavy elements in binary neutron-star mergers from a gravitational-wave event,” Nature 16 October 2017 (abstract), as well as Arcavi et al., “Optical emission from a kilonova following a gravitational-wave-detected neutron-star merger,” Nature 16 October 2017 (abstract) and work from there. The UC-Berkeley news release cited above contains links to a variety of key sources.

by Paul Gilster | Oct 20, 2017 | Outer Solar System |

Centauri Dreams returns with an essay by long-time contributor Alex Tolley. If we need to grow a much bigger economy to make starships possible one day, the best way to proceed should be through building an infrastructure starting in the inner Solar System and working outward. Alex digs into the issues here, starting with earlier conceptions of how it might be done, and the present understanding that artificial intelligence is moving at such a clip that it will affect all of our ventures as we transform into a truly space-faring species. Under the microscope here is a company called SpaceFab, as Alex explains below, and the potential of ISRU — in situ resource utilization. Emerging out of all this is a new model for expansion.

by Alex Tolley

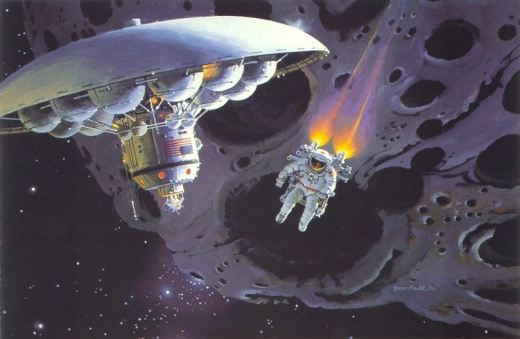

“Asteroid Facility” – Syd Mead

To sail the heavens and reach the stars is extremely expensive. With the technologies we can currently envisage, Earth’s GDP will need to be orders of magnitude larger to support a starship program. Unfortunately, the Earth is likely to hit environmental and economic limits well before we reach the necessary size of a starship building GDP. One solution is for humanity to expand into the solar system to grow the economy with the vast resources available out there [5]. Science fiction novels are replete with tales about self-reliant belters extracting wealth from the asteroids, while followed by adventurers, gold-diggers and chancers, that recapitulate the myths of the “Old West” and the US’ manifest destiny [1].

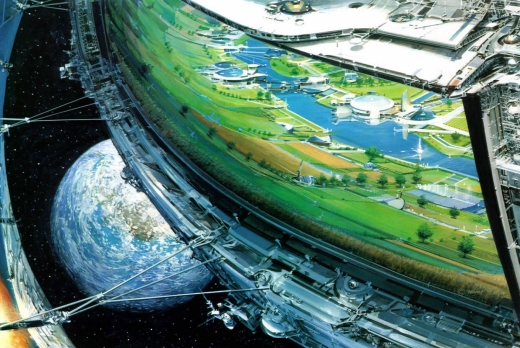

Space Habitat – John Berkey

By the late 1970s, establishing space colonies and selling solar power to Earth [2] was the idée du jour. Allen Steele popularized that vision, regaling us with stories of men and women living and working on the high frontier [3]. In reality, the cost of transporting and housing space workers is astronomical compared to those of ocean rig workers whose jobs those high-frontiersmen emulated. An economy supporting a wealthy, post-scarcity civilization living throughout the solar system and able to support starship exploration became more fanciful, and we focussed on scaling back our starship ambitions with 1-gram, laser-propelled, sail ships that might launch half a century hence.

Exploring the Asteroids – Robert McCall

Exploring the Asteroids – Robert McCall

While the prospects for humans in space dimmed somewhat, a renewed flowering of developments in AI and robotics burst onto the scene with capabilities that astonished us each year. On the endlessly orbiting ISS, while astronauts entertained us with tricks that we have seen since the dawn of spaceflight, autonomous robots improved by leaps and bounds. Within a decade of a DARPA road challenge, driverless cars that could best most human drivers for safety appeared on the roads. Dextrous robots replaced humans in factories in a wide variety of industries and threaten to dramatically displace human workers. DeepMind’s AlphaGo AI beat the world’s champion GO player with moves described as “beautiful” and well within the predicted time frames. In space, robotic craft have visited every planet in the solar system and smart rovers are crawling over the face of Mars. A private robot may soon be on the Moon. In orbit, swarms of small satellites, packing more compute power than a 1990 vintage Cray supercomputer, are monitoring the Earth with imaging technologies that equal those of some large government satellites. On Earth we have seen the birth of additive manufacturing, AKA 3D printing, promising to put individual crafting of objects in the hands of everyone.

What this portends is an intelligent, machine-based economy in space. Machines able to operate where humans cannot easily go, are ideally suited to operating there. Increasingly lightweight and capable, and heedless of life support systems, robotic missions are much cheaper.. How long before the balance tips overwhelmingly in the machines’ favor? Operating autonomously, advanced machines might rapidly transform the solar system.

In a previous post, “A Vision to Bootstrap the Solar System Economy” [4], I looked at an academic paper that laid out an idea of self replicating robots that would start harvesting lunar resources and eventually expand operations out to the asteroid belt. The power of exponential growth to bootstrap such a system was clearly evident, allowing a relatively tiny investment to create a huge manufacturing capability of staggering size within a short time with growth rates far exceeding our current human-based economies. An interesting idea and vision, but was anyone going to consider developing a business using that approach? A new company, SpaceFab, shares a similar vision. The founders want to create a fleet of mining and fabrication robots that will extract raw materials from the asteroids to create refined commodities and products in space, including building more robot miners and fabricators. A grand vision, but how do they envisage it being done?

While the original idea of asteroid mining was to extract the non-volatile resources, especially the high value platinum group metals [5], more recently the focus has shifted to volatiles, primarily water, for life support and chemical rocket fuels. SpaceFab however, prefers the extraction of the more abundant iron and nickel, whose current value in space is principally their launch cost. Their argument for this focus is twofold. Firstly, water is relatively rare in most near Earth asteroids (NEA) and therefore likely to be more difficult to extract from those bodies. While common in asteroids beyond the frost-line or in dead comets [10], the delta v cost is high and journey times much longer. Conversely, metals are far more accessible inside the frost-line with NEAs, reducing both the cost to acquire these metals and the mission cycle time. Secondly, SpaceFab is looking to extract iron and nickel using simple, lightweight and low-cost processes like magnetic collection of material, and induction heating to melt and refine the metals. Their view is that the path to profitability is faster with this approach than prospecting and extracting volatiles.

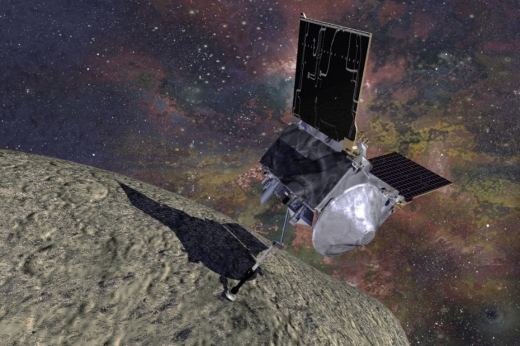

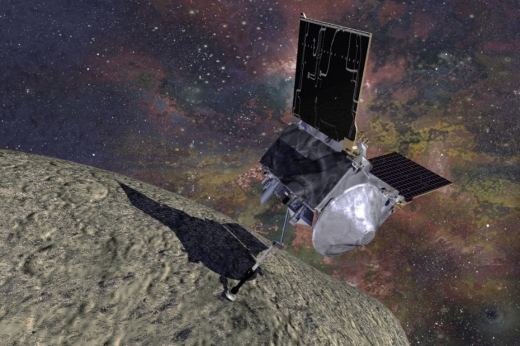

The OSIRIS-REx mission is NASA New Frontiers mission to return a sample of an asteroid (101955 Bennu) to the Earth. Mission cost is approximately $800 million (excluding the launch vehicle.). – Lockheed Martin

SpaceFab believes that they might get a sample return mission to an M-type asteroid within 10 years and a mining craft 5 years later. Their design target is for a craft just 1 MT in mass (about the same size as OSIRIS-REx), and consists of an ion engine, rock scraping tools for extracting material, and some form of electrical induction heating to produce refined ingots. When sufficient extraction is achieved those refined ingots could then be used as feedstock for space manufacturing. While apparently ambitious, the concept of small craft to mine asteroids has been developed by Calla, Fries and Welch and was presented in two papers at the IAC in 2017. Their craft were designed to be less than 500Kg. Water in close by NEAs was their objective based on their analysis of extraction methods which indicated using microwave thermal heating. Teleoperation from Earth was assumed and therefore an NEA within 0.03 AU was preferred. The small size combined with a swarm model for redundancy was the most economically modeled approach to provide a large and early return on investment [15,16].For robotic craft on deep space missions, high Isp electric engines reduce costs, as the lower propellant mass means lower launch costs. To keep costs low, SpaceFab intends to use off-the-shelf ion engines that may be augmented by their ion accelerator technology (patent pending) that they claim boosts Isp several fold. With the Dawn mission spacecraft’s NSTAR ion engine having an Isp of 3100s, Spacefab might hope for an augmented Isp of up to 10,000s. The addition of this accelerator unit and the solar panels to power it should increase the mass ratio performance of the craft.

So far SpaceFab’s approach seems similar to other schemes to mine asteroids. Where SpaceFab’s vision really differs is the use of ISRU (in situ resource utilization) for construction of onsite mining and fabrication tools. Rather than hauling out machine tools to an asteroid to extract and fabricate components, SpaceFab plans to reduce the mining craft’s mass, and therefore cost, by building many of the machine tools for mining and fabrication using local resources. It is just one step further to replicate the whole craft. This model of self replication of much of the mass of the machines is similar in concept to the robot bootstrapping paper and promises to open up exponential mining and fabrication possibilities, while making the owners quite wealthy.

Most asteroids are too far away to allow teleoperation of the sort that would work on the Moon or with close NEAs. This rules out complex manufacturing guided by human controllers. The intelligence needed to prospect, mine and process ores must be local. Beyond some human oversight, these robot mining craft and fabricators will need to be highly autonomous. This requires advanced AIs. While we are not close to that goal today, the rapid pace of development of AI software and specialized chip hardware promises to make this a reality sometime in the projected time frame. Such craft will be able to navigate to a selected asteroid, prospect it, extract and refine metals, and then fabricate machine tools and manufacture components. SpaceFab believes that such craft could even provide a “manufacturing on demand” service in space. On Earth we have seen the birth of additive manufacturing, AKA 3D printing, promising to put individual crafting of objects in the hands of everyone. The technology is already being tested on the ISS to reduce the number of spare parts that must be shipped.

Fabrication, even self-replication, is no longer a science fiction concept. Nasa has a “FabLab” program to investigate the best ways of using that technology to facilitate spaceflight as a result of its success with 3D printing experiments on the ISS. Neil Gershenfeld’s lab at MIT has designed a method of robotic self-replication suitable for use in space. The current proposed system can fit inside a CubeSat [14]. The basic technologies needed for SpaceFab’s vision are already in place, just requiring further development.

The eventual goal of robot miners and fabricators producing commodities and goods at a fraction of today’s prices, via massive supply expansion, may face some short term obstacles. Low launch costs spearheaded by NewSpace companies like SpaceX could make placing raw materials in space cheaper than space mining, for cis-Lunar infrastructure. However, space fabrication of components in situ is a useful goal, regardless of the raw material source. In the 1980s, K. Eric Drexler intended to manufacture ultra-light, aluminum solar sails in space. T. A. Heppenheimer described manufacturing trusses for solar powersat arrays using relatively dumb, machines bending and welding rolled sheets of aluminum. Grumman Aerospace had a working prototype “Composite Beam Builder” by the time Heppenheimer’s book [5] was published. More recently, NIAC has funded space fabrication projects using more sophisticated robotic builders.

At some point, regardless of cost, the sheer volume of resources for expanding the economy will require sourcing from space to overcome the Earth’s limitations. Robotic mining and fabrication will then become the norm. As with newly industrializing Earth-based economies, initial fabrication may be for simple, low value added, bulk commodity products, but eventually as capabilities increase, higher value added manufactures will be possible.

Although initially limited by key components like advanced computer chips, over the long term, self-replicating craft would evolve into Von Neumann replicators. Philip Dick invented the term autofac for factories that could construct themselves from seeds and self replicate [6]. While Von Neumann machines are just self replicators, autofacs also generate outputs, much as honeybee colonies also produce excess honey. Such self-replication and fabrication infrastructure could produce a vast range of products for the solar system economy.

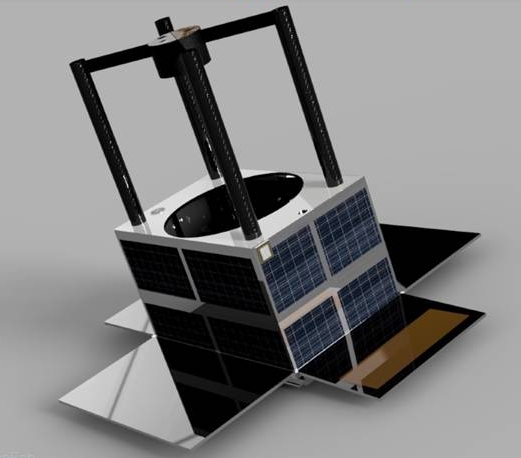

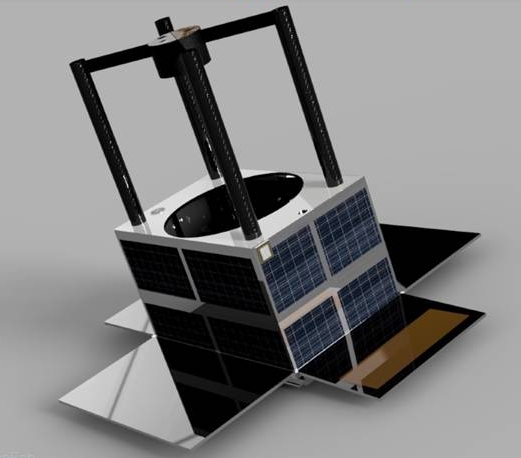

SpaceFab’s Waypoint Telescope – engineering mockup.

To reach the goal of space mining and manufacturing without the deep pockets of a Deep Space Industries or Planetary Resources, SpaceFab intends to enter the orbital satellite observation market. They have designed a low cost, high resolution (1 meter ground resolution) telescope that can be used both for astronomical and Earth observation purposes, using a variety of imaging sensors and filters that offer the range of imaging outputs suitable for both markets. Currently they are crowd-funding their initial prototype telescope which will be followed by a flight ready telescope for a 2019 launch. By launching a fleet of such telescopes, they expect to penetrate this market by offering the lowest price imaging and analysis services.

This observation service would then produce the profits needed to develop the asteroid mining craft and bootstrap the space fabrication business. Interestingly, SpaceFab currently has no intention of using these observation satellites to prospect for suitable asteroids as DSI intends, but rather to use existing information to enable a mission to an M-type NEA. As this information will not be detailed enough for detecting higher quality ores, the spacecraft will need to be smart enough to do their own prospecting on arrival at an asteroid. SpaceFab speculates that in the near term, the value of fairly pristine asteroidal material may be higher for research than its commodity price and may offer a faster path to early profitability.

Once mature, self-replicating fabs promise a future that has vastly expanded horizons and implies a post-scarcity economy. Once such seed factories become ubiquitous, there is no reason why they could not venture to other solar systems and replicate there. Even if slow, perhaps travelling at 1/100th c, they would reach the nearer stars in half a millennium, creating all the materials and habitats for humans to occupy. This is the model that Asimov’s “spacers” envisaged for themselves [7], their robots preparing the way for them to follow. The colonization process would be with a wave of machines preparing star systems for the following human starships.

It is a dazzling future to contemplate if it unfolds this way.

References

- Anderson, Poul. Tales of the Flying Mountains. Tom Doherty Associates, 1970.

- O’Neill, Gerard K. The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space. Morrow, 1977.

- Steele, Allen M. Sex and Violence in Zero-G: the Complete Near-Space Stories. Meisha Merlin Pub., 1998.

- Tolley, Alex “A Vision to Bootstrap the Solar System Economy” https://www.centauri-dreams.org/?p=36963

- Lewis, John S. Mining the Sky: Untold Riches from the Asteroids, Comets, and Planets. Addison-Wesley, 1998.

- Heppenheimer, T. A. Toward Distant Suns. Stackpole, 1979.

- Dick, Philip K. “Autofac.” The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick, Subterranean Press, 2010.

- Asimov, Isaac. The Robots of Dawn. Bantam Books, 1994.

- SpaceFab http://www.SpaceFab.us/

- Graps, A et al. “In-Space Utilization of Asteroids – Answers to Questions from the Asteroid Miners”, ASIME 2016: Asteroid Intersections with Mine Engineering, Luxembourg. September 21-22, 2016. arxiv.org/abs/1612.00709

- Brophy, J., et al. “Asteroid Retrieval Feasibility Study” (2012). Keck Institute for Space Studies, Caltech, JPL. kiss.caltech.edu/final_reports/Asteroid_final_report.pdf

- Welch, C., et al. Asteroid Mining Technologies Roadmap and Applications (ASTRA)” (2010) , International Space University isulibrary.isunet.edu/opac/doc_num.php?explnum_id=73

- Mazanek, D. “Asteroid Redirect Mission Concept: A Bold Approach for Utilizing Space Resources.” Acta Astronautica, Pergamon, 23 July 2015, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0094576515002635.

- Langford, Will, et al. “Hierarchical Assembly of a Self-Replicating Spacecraft.” 2017 IEEE Aerospace Conference, 2017, doi:10.1109/aero.2017.7943956.

- Calla, P., Fries, D., Welch, C. “Analysis of an Asteroid Mining Architecture utilizing Small Spacecraft”, IAC 2017

- Calla, P., Fries, D., Welch, C. “Low-Cost Asteroid Mining Using Small Spacecraft”, IAC 2017

by Paul Gilster | Oct 6, 2017 | Culture and Society |

I know I said I wouldn’t post for a bit, but because I’ve just given my closing remarks at the Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop, they are ready to go for publication, and I thought I would go ahead and publish them here. I did much of the actual writing for this at the conference (where I still am), so there may be a few typos. I haven’t inserted the affiliations of the speakers, either, but I’d like to go ahead and get this up. My plan, once I’ve taken care of other obligations in the next ten days or so, is then to return to TVIW with greater focus and look at specific papers that caught my eye and the ways they fit in with the larger interstellar picture. For more background on the speakers here until then, check the TVIW 2017 Symposium page. I also didn’t mention the excellent workshop sessions in this talk because they had just been summarized immediately before my own talk. But more on them as well as other TVIW observations when I return to regular Centauri Dreams posts. This should be around mid-October.

I want to thank Les Johnson and the conference organizers at TVIW, Tau Zero and Starship Century for the opportunity to make this presentation, and for the huge outlay in time and energy they devoted to the event. That includes our workshop leaders and participants who carried the original workshop notion forward. What I now hope to do is give an overview of what we have done here and what it signifies.

Somewhere around the 6th Century BCE, a man named Lao Tzu, an almost legendary philosopher and writer, purportedly produced the book known as the Tao Te Ching, a fundamental text of Taoism and Chinese Buddhism. This year’s Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop arrived made to order for Taoist thought, with its theme “Step by Step: Building a Ladder to the Stars.” Because for years I’ve used as the line on my digital signature the Tao Te Ching’s aphorism: “You accomplish the great task by a series of small acts.” Confucius, who may have known Lao Tzu, would echo the same philosophy.

As anyone paying attention to this year’s sessions learned at the beginning, many of the acts we are trying to accomplish are anything but small. A 100 GW laser array is not small either in concept or in physical dimension. A sail five meters to the side is small by many earlier standards, but what we discuss doing with it, a mission to the nearest star, is not small, nor is the exploration of the outer Solar System — with precursors fueled by fusion or driven by plasma sail — a small accomplishment. But conceptualizing each of these things, one at a time, that is a series of small steps, and we need many such steps.

The emergence of Breakthrough Starshot clearly changes the game for everyone in the interstellar community. We have a congressional subcommittee report that ‘encourages NASA to study the feasibility and develop propulsion concepts that could enable an interstellar scientific probe with the capability of achieving a cruise velocity of 10 percent of the speed of light.” I doubt seriously that that phrasing would have emerged without the powerful incentive of the funding provided by Breakthrough, nor would the Tau Zero Foundation’s recent grant.

We’re on new terrain that is a long way from where we once were, in the days when there were few interstellar meetings as such and most discussions among those of an interstellar bent happened at occasional get-togethers in meetings on largely different subjects. Today we have a community and, if it is one with a pointing problem in terms of how often it meets and how well it stays focused, it is at least one with high energy levels and a steep drive to succeed.

TVIW 2017 gave us a range of focused sessions which I have chosen to group, trying to avoid being too arbitrary, into loose themes. Pete Klupar gave us the Breakthrough overview, which includes the welcome and related work of both Breakthrough Watch and Listen, a reminder that we must gain more information about the target of our mission, and indeed decide whether there may not be an even more attractive target near Centauri A or B. The welcome news that the RFP process has begun with work on the project’s laser array shows us a community with an actual interstellar project seriously defining the parameters of a mission.

Here we are in the larger realm of vision, as Andrew Siemion reminds us when he tells us that we search for ourselves as we venture to the stars. We also, whether or not we send Starshot sails on their journeys in 40 or 50 years, define the limits of our present technology and infuse the entire enterprise with an unprecedented prospect of well funded trade studies. The interstellar enterprise advances whether or not Starshot’s sails launch to Centauri, and who can say what spinoffs we won’t gain from the effort in the interplanetary arena with its tools.

On the matter of overview, let me mention Marc Millis’ discussion of the Tau Zero grant from NASA, which as I mentioned derived from the impetus of the Starshot initiative. Comparing propulsion approaches to take us through what Millis calls the era of precursors, the era of infrastructure and the non-extrapolatable future helps us identify the critical issues that need study, just as Starshot itself helps us locate, one by one, the major problems we need to solve for a specific mission concept. What we do need to be wary of is premature lock-in when competing methods for doing interstellar missions remain very much on the table.

In the realm of hard decisions and trade studies that illuminate them, Kevin Parkin showed us a system model that allows Starshot to study not only a Centauri mission at 20 percent of c, but also a precursor mission to a closer objective and a 70 km/sec ground vacuum tunnel test facility. It is heartening to realize that Parkin’s system has been used to conduct trade studies since March of 2016.

Meanwhile, the inputs from the broader community continue. Al Jackson showed us an analysis of trajectories for a Starshot probe, and we’re reminded by Benjamin Diedrich, who has been working with the NEA Scout mission, that we can learn much from a mission with a much different objective, and one with the ability to apply guidance and control forces that our Centauri-bound sail will be unable to muster. Congratulations to Diedrich and particularly Les Johnson for the recent successful deployment tests of the NEA Scout sail.

I want to also mention in the realm of trade studies and laboratory work the importance of the kind of measurements George Hathaway discussed for any work of this kind. Looking at problems in testing high voltages in high vacuum at cryogenic temperatures, Hathaway showed the measurement pitfalls that can ensnare experimenters, hard lessons to be kept in mind at all times by those who are evaluating propulsion technologies both understood and exotic.

Starshot’s mission components were a major factor in our deliberations. That 100 gigawatt laser array that Robert Fugate described can put something on the order of 30,000 g’s on the sail if we can get it to operate, despite the major issues of laser phase noise, optical path length differences, atmospheric fluctuation and pointing accuracy. We are considering a sail that goes from Earth orbit to 10 times the distance of the Moon in a matter of hundreds of seconds.

Can we make this happen? Starshot fails if it does not, and it fails if Jim Benford and those working with him cannot come up with a sail that can withstand the huge forces to be slammed into it. Here I want to pause to mention the rich sail background on display at the conference. The Benford brothers did the first work on sails in the laboratory — and as far as I know — the first actual tests of beamed sails, some 16 years ago. In the audience, we had Gregory Matloff, a distinguished figure in sail history who has been examining their prospects for decades.

Geoffrey Landis has published key papers on sail materials, and although his role in this TVIW was to discuss the Solar Gravity Lens, his contributions help us as we look toward possible sail materials and shapes within the Starshot envelope. The welcome presence of Giancarlo Genta reminds us of the tremendous contribution of the Italian sail effort through Project Aurora and other work in the 1990s. The need for the kind of sail test facility Jim Benford so carefully described is obvious and one hopes it will be the target of quick action, especially with the new wave of RFPs starting to translate the concept into reality.

Phil Lubin’s analysis of directed energy as the enabler for interstellar missions, beginning with a NIAC Phase 1 study under the name Starlight, led to Pete Worden’s making the connection with sails as a possible driver for a Centauri mission with a wafer scale payload. I was sorry that Mason Peck wasn’t here to participate in the discussion given his role in ‘spacecraft on a chip’ through his work at Cornell, but Lubin reminded us that an infrastructure like this can do much more than drive chip spacecraft. It can become a huge factor in planetary defense, in power beaming to Earth, in space debris removal and beamed transport within the Solar System.

Giancarlo Genta presented a preliminary analysis of inflated spherical sails of the kind recently proposed by Avi Loeb and Zac Manchester for Breakthrough Starshot. Working at far lower power levels for beam intensity, Genta found that an inflated sail essentially holds its shape under beam power, using a one meter diameter sail at 30 g’s acceleration. Further testing at increased power levels approximating Starshot are ahead. Key questions include whether hitting a sail with 30,000 g’s will not both deform and spin the sail, although as Genta pointed out, the sail can be abandoned for the duration of cruise if it can be brought safely up to speed.

I heard several people in the audience calling communications back to Earth the biggest challenge for Starshot, and although Dr. Fugate might disagree, I have to say that David Messerschmidt’s talk on data return was sobering. We have to make up 7 orders of magnitude of signal power when compared to our outer Solar System missions, perhaps a doable proposition if we allow decades for data return. We also deal with formidable issues of background radiation, pointing accuracy, atmospheric turbulence and scattering, and optical losses. All these factors push an increase in aperture area to 565 meters.

Our communications and imaging discussion, though, also takes in Slava Turyshev’s work on imaging an exo-Earth with the Solar Gravitational Lens. Clearly, getting a good idea of our target from a technology that could allow images of 1000 x 1000 pixels would be an outstanding precursor in its own right, and one that could be used at distances up to 30 parsecs if we can make it work. Geoff Landis’ reservations about the Gravity Lens don’t question its potential but do make us ask how likely we are to make it work and deliver genuinely useful information.

We got into these matters at the Sagan session on the 550 AU mission that Claudio Maccone has called FOCAL, where Landis, Turyshev, Greg Matloff and Pontus Brandt debated the issue. It should be kept in mind that some of Maccone’s recent work on the lens has shown the potential for communication, a feature that, if it could be realized, would suddenly turn many of the issues David Messerschmidt examined on their head. Thus, if it could be determined a lensing option is workable, an early Starshot mission to explore this region is a possibility.

Let me also mention the Sagan session on detecting life through biosignatures in planetary atmospheres in which I spoke along with Greg Benford and Angelle Tanner. This is by way of looking at what we can learn about nearby stars, the fact being that nearby red dwarfs are going to be under intense scrutiny by the James Webb Space Telescope, and we have the possibility of detecting gases like oxygen and methane which, if found together, offer us a strong indicator of some kind of metabolism. Tanner’s analysis of planet finding techniques in a later session took us through the range of methods available, ranging from radial velocity to direct imaging and transits, particularly in terms of distinguishing stellar noise from terrestrial mass planets.

We moved into the realm of other interstellar precursor missions with Pontus Brandt’s discussion of probe missions to 200 AU up to 1000 AU. This gets us into virgin territory, for going to this distance puts us into the relatively pristine interstellar medium. Quaoar lines up as an interesting target along the way because of what it may tell us about the KBO population, but we also would learn a great deal about dust distribution within the system, seeing the heliosphere from outside as we see similar astrospheres around other stars. Brandt’s comments on how we manage long-term missions ring true in the era of decadal data return from a Starshot mission and destinations that may require more than a single lifetime.

Gary Pajer’s take on precursors would use the Princeton Field Reversed Configuration machine to reach out to that magical 550 AU target, where the lens effects begin, with a mission time of 13 years, or 18 if we choose to stop. Using this technology, an Alpha Centauri flyby becomes feasible within 550 years, with both power and propulsion generated by a single engine.

Could we do this with a solar sail mission? Olga Starinova asked that question, noting a close solar flyby based on recent studies by Greg Matloff, Les Johnson, Claudio Maccone and Roman Kezerashvili to reach the inner Oort Cloud within 30 years. And Stacy Weinstein-Weiss discussed a key interstellar question: Why is science return from an interstellar mission better than local studies from Earth? Here, we learned about the unique science measurements that would be performed en route to the exoplanet, including the outer regions of our solar system, the Oort Cloud, the local interstellar medium, and the astrospheric environment around the host star. Perhaps trumping all of these is the search for life with in situ measurements.

Richard London and James Early helped us understand the dust impact hazard, which they believe will not threaten a sail, but of course our concern is likewise with the payload, which must be protected at all costs. London and Early used the HYDRA code for inertial confinement fusion in this work to study how we might reduce risks using optimal materials on a fast-moving craft’s leading side, with leading thin foil to atomize dust grains. Robert Freeland pointed out to me that one of Jeff Greason’s plasma magnet sails, discussed in a moment, could also serve as a useful shield.

On useful precursor technologies, Sandy Montgomery provided a way to avoid growth in the boom diameter and mass of sails as we move toward larger-scale missions by using what he calls a ‘space tow architecture,’ a train of gossamer sails integrated with a tension truss column. The advantages: We get much larger sails without growth in boom diameter and mass, using lightweight longeron filaments to connect a stack of smaller sails, much like a tandem kite.

I had mentioned to Pete Worden in a recent online exchange that I had seen several small sail analyses springing up and asked if they had any connection with Starshot. His answer was that they didn’t, but as he put it, the more the merrier given the magnitude of the problem. Thus it’s tremendously heartening to see the outgrowth of sail ideas that may eventually influence Starshot or, more likely, feed into designs outside of immediate interstellar goals that could play into our move toward the space-based infrastructure we need here in our system.

Thus Grover Swartzlander’s analysis of diffractive meta-sailcraft, which proposes that we look more carefully at diffractive sails, which absorb little light — a key issue for beamed sails — and have none of the re-radiation problems of reflective materials. Moreover, we might recycle photons to multiple sail layers if we can develop the right broadband space-qualified diffractive films.

TVIW 2017 was marked by its focus on sail technologies, due to all the factors I’ve already mentioned, but of course we have other options to consider. Jason Cassibry talked about the problems of solid state nozzles when dealing with pulsed fusion and fission/fusion hybrids for rapid precursor missions, the primary issues being erosion and wall heating. He showed us a 3D plasma simulation of a pulsed magnetic nozzle crafted for z-pinch propulsion.

Pauli Laine examined fission fragment possibilities, given the fact that uranium fission releases 81 percent of its energy in the form of kinetic energy. The escape of fission fragments rises when particle size decreases, so low density fissile material like americium or curium comes into play, with the escaping fission fragments being used as rocket propulsion. As Laine noted, fission fragment advocates also have to contend with fuel production — how to produce enough of the needed materials — as well as daunting issues of using such rockets safely.

Antimatter appeared in two sessions this year, with Gerald Jackson describing crowdfunded ongoing experimentation into antimatter production. Jackson would like to see antimatter emerge at a rate of at least 1 gram per year, a startling figure given that I can remember when NASA gave a figure of $62.5 trillion per gram of antihydrogen. Measure this against a Fermilab production rate of 2 nanograms per year. If we can do this in a way that is economically feasible we have the option of missions like the antimatter sail that Jackson and Steve Howe, also at Hbar, has developed through NIAC work. Jackson also examined antimatter storage possibilities through diamagnetic levitation.

Antimatter storage was the key of Marc Weber’s talk, which looks at the problem of controlling space charge, the repulsive force of all those stored charges in the fuel we would like to use. Weber is experimenting with storing electrons in a massively parallel micro-array of tubes in a 7-tesla magnetic field, seeking to discover the possible configurations in trap arrays. Everyone in the interstellar community from Les Shepherd and Robert Forward on has pondered the energetics of antimatter rockets, which still face the daunting storage and production issues Weber and Jackson have explored.

A bit less exotic but with exciting potential of its own is the plasma magnet sail described by Jeff Greason. Here we can imagine deploying magsails for braking against the interstellar medium as an interstellar probe enters a destination system, achieving orbit around the target star using the stellar wind. But Greason pointed out that such technologies are likewise ideal for precursor missions to 1000 AU, for example, and conceivably, using local beamers, within braking systems for a fast mission infrastructure inside the Solar System including cycling systems to Mars. Greason considered using particle beams and even fusion pellet delivery to the sail.

I should mention that a Sagan session also explored flyby vs. deceleration with the help of Jackson, Stacy Weinstein-Weiss and Gerald Jackson, along with David Messerschmidt. The deceleration problem looms large. If we do get Starshot probes to Proxima Centauri, the imagery we receive may well make clear the need for a sustained presence in that interesting system. The payoff, as Weinstein-Weiss made clear, would be in the search for extraterrestrial life, where we may need all the resources we can muster to verify a detection.

Talking about interstellar mission concepts reminds me inescapably of a loss we suffered this year in science fiction writer Jerry Pournelle. Familiar, I think, to most of us here, Jerry explored numerous interstellar schemes including beamed sails (early on), and in Footfall used Orion technology to save the species.

Because Larry Niven wrote Footfall with Pournelle, I want to mention how pleased I was to be able to shake his hand at long last. Larry brought a whole new dimension to my science fiction reading back in the early 1970s with short stories and the novel Ringworld. What a compliment to TVIW to have Larry along with writers Geoff Landis, James Cambias, Greg Benford and Alan Steele here for tonight’s writers’ panel, not to mention our host Les Johnson himself. About Steele, I want to say that I’ve read Arkwright twice, and if you don’t know the novel, you need to acquire a copy immediately, as it addresses the issues a small community of devoted advocates face when trying to do something as outlandish as build vehicles that can move between stars.

The valedictory theme continues: Let me also mention that this year we lost Jordin Kare, an innovative physicist who came up with ideas like SailBeam, a stream of micro-sails delivered to a receding starship as a form of propulsion, and the Bussard Buzz Bomb, as he called it, a starship that came up to speed through collision fusion with a string of pellets that had been laid out along a predetermined track. I never met Jordin, but he spent a lot of time on the phone with me when I wrote my Centauri Dreams book, and I think the field is diminished by his passing.

The infrastructure theme emerged several times at this year’s sessions, with Tracie Prater looking at NASA’s In-Space Manufacturing Project, under the theme Make It, Don’t Take it. And it only makes sense as we contemplate long-term manned missions that we look at manufacturing and recycling parts on demand, using the ISS while we can, before its 2024 deorbit, as a testbed. We learned about NASA’s plans for a multi-process fabrication laboratory called FabLab, with current experiments on the ISS pointing to a robust future for assembly of materials in space with 3-D printing technology.

Jon Barr told us about the United Launch Alliance’s robust work with ACES (Advanced Cryogenic Evolved Stage) and XEUS, a vertical-landing, vertical-takeoff lunar lander demonstrator. Can we use these refuelable, reusable technologies in company with the Vulcan booster to establish what will become trade routes to Cislunar space? The idea here is connecting Low Earth and Geostationary Orbits with Earth Moon L1 and the lunar surface. The goal: A robust Solar System economy, which will eventually translate our early interstellar precursors like Starshot into a longer-term framework of exploration and perhaps colonization.

Our leadership panel included Rep. John Culberson, whose language we’ve already discussed regarding a NASA inquiry into interstellar prospects to coincide with the anniversary of the Moon landing in 2069. Also Congressman Brooks of Alabama, Lt. General Kwast and Paul McConnaughey, who directs Marshall Space Flight Center. It was rousing to hear the energy in Rep. Culberson’s voice as he described missions like Europa Clipper and the possibilities of the Space Launch System. A takeaway was his belief that the discovery of life, either in our system at Europa or Enceladus, or in biosignatures in an exoplanet atmosphere, will be a civilization-changing discovery that ignites public support for future exploration.

But it was also sobering to consider the budgetary dilemmas of ever-rising deficits and accumulating national debt. Lt. Gen. Kwast emphasized that expansion into space demands we take our values with us even as we plan missions to ever more distant targets. The panelists’ responses to Pete Klupar’s concerns over installations like the Starshot 100 GW laser show that we still have many policy questions to answer as private initiatives like these go forward.

Can we get beyond bureaucracy and current cultural fatigue to expand the realm of values responsibly? Brent Ziarnick reminded us that interstellar technology presents us with the most daunting energies human beings have ever thought to develop. The analogy with nuclear energy is clear, and fortunately supported by deep scholarship. Our preoccupation with nuclear gloom, part of Sheldon Ungar’s ‘dynamic oscillation’, as Ziarnick described, ended Project Orion and threatens our development of nuclear power options as a positive tool for exploration.

Is METI likewise an ethical issue? Kelly Smith asks whether scientists are up to the challenge of dealing with broadcasting to the stars, given that this is a matter that potentially involves the entire species. METI may be low risk, but the risk is not zero, and that risk involves the survival of the entire species. Or what about the ethics of sending humans to the stars?

For we may discover that exoplanets are not empty, but filled with life. And given the fact that we use but 21 specific amino acids to build our proteins — and that there are some 300 naturally occurring amino acids — we cannot know what life may choose to use. Perhaps, as Ken Roy reminds us, we might look for lifeless worlds on purpose, seeking places we can terraform.

We’re now looking at issues of humans among the stars, a future that could involve vast worldships taking human populations to distant systems. Ore Koren discussed the vital question of how we reduce conflict in a closed environment in which causes of violence are numerous. Koren used large datasets to look at historical examples of violence, along with strategies by which we might reduce problems like lack of external ideas and migration. The result: Our worldship emerges as multicultural and semi-centralized, a hybrid of Sweden and Singapore.

James Schwartz worked similar turf but examined the ethics of worldship travel itself. Are colonists on dubious ground imposing a worldship future on their children? Perhaps not, but the real question becomes, should we put parents on worldships in the first place? Schwartz reminded us of the need for sufficiently large crews, and the fact that we will use extraterrestrial settlements much closer to home to learn valuable lessons before embarking starward.

And there we are, TVIW 2017. Thank you all for the opportunity to listen to and learn from your deliberations. If there is one thing that the interstellar community has taught me, it is that scientists working at the top of their form are willing to listen to questions and explain their work to writers like me, and to put breathtaking concepts out to a receptive and growing audience like those who gathered here. This is a mission that all of you make possible, and while it may seem less dazzling than a Starshot, it is vital in making our interstellar effort a planet-wide affair.

I close by returning to Lao Tzu: “To avoid disappointment,” says the Tao Te Ching, “know what is sufficient. To avoid trouble, know when to stop.”

I’m done.

Exploring the Asteroids – Robert McCall

Exploring the Asteroids – Robert McCall