Aniara… The Musicals

Aniara was a major literary hit in Sweden when the epic poem was released there in 1956 by its native son, Harry Martinson. The poem would later become a cultural treasure of that northern European nation.

As often happens when a cultural work becomes a phenomenon, the regional artistic community/industry capitalized on Aniara and soon created their own versions and interpretations of the original vision.

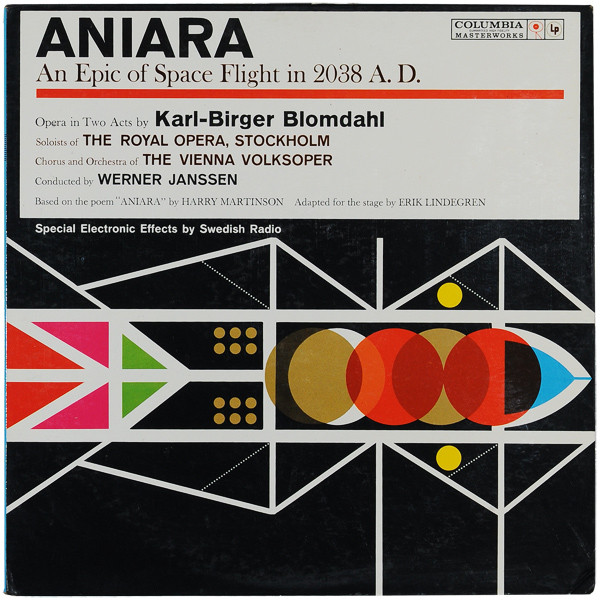

The first major adaptation of Aniara was as a two-act opera produced by Karl-Birger Blomdahl (1916-1968), a Swedish composer and conductor who was originally educated in biochemistry. The opera had its premiere on May 31, 1959, at the Royal Swedish Opera in Stockholm. The production was recorded and then released the following year on four LP records by the Columbia Masterworks record label, which you can listen to and see here:

https://archive.org/details/lp_aniara-an-epic-of-space-flight-in-203_karl-birger-blomdahl

The subtitle on the album cover is interesting: “An Epic of Space Flight in 2038 A.D.” While an exact date was never given in the poem or any other version of the work that I am aware of, it is rather implausible now to imagine the era in Aniara taking place so relatively soon, even from the perspective of 1960. Not so much the possibilities for nuclear war or climate disruption, but rather an interplanetary culture with thousands of spaceships plying the void and permanent settlements on Mars and elsewhere – to say nothing of the space elevators shown and mentioned in the 2018 film.

COMMENT: There is one mention of the Twenty-Third Century in the poem, but the work seems to be referring to that century as an earlier time from their present.

The album front cover to the Columbia Masterworks (catalog number M2S 902) recording of the opera Aniara. Note the abstract design of the spaceship and the year above it: This date appears nowhere in the poem and would be too soon even from the perspective of the album’s release year.

The page linked above also displays both sides of the Aniara opera album cover, an extensive story background and commentary written by Harry Martinson himself, the complete transcript of the opera translated into English, and even shows the four LP records themselves. They are presented in several formats, including this PDF version:

In the introduction, Blomdahl explains how he adapted Martinson’s poem into an opera:

The original version of Aniara was too long to use as a libretto. It was therefore necessary to select to arrive at a satisfactory scenic and musical result. This rearrangement has been done by the poet, Erik Lindegren [1910-1968], who not only possesses a sound instinct for musical coherence and dimensions but is also able to incarnate it on the stage. His aim has been to reproduce the suspense of the original epic, but he has simplified and concentrated it to achieve the right dramatic impact for opera.

Harry Martinson has shown his understanding of the demands made upon his work by opera and has added to his original manuscript:

Aniara is a ‘situation opera, a collective drama of mankind in the Space Age, which Martinson himself aptly designates as a ‘panorama’ and ‘revue’. While the scenes are mostly concerned with mass psychology, certain individuals stand out and thereby illustrate their conflict with the group – which is portrayed in both its positive and negative aspects. A second fundamental conflict is that which pits men’s fear of space against their longing for the old idyllic life on earth; it is, in other words, the conflict between being adrift and being firmly anchored in ‘nature.’

The album section titled “The Story of ANIARA” includes some very interesting insights into the piece by Martinson himself, as quoted next:

Surrounded by desolate space and banished from the community of our solar system, the Aniara people begin to discover the full extent of their human misery. Life acquires a different and hitherto unknown meaning for them. Death takes on an unsuspected immensity, becoming synonymous with space itself, while the protective walls of the Aniara symbolize the brevity of life. At the same time, however, these walls mercilessly reflect the spiritual poverty within their confines. Yet no galaxy is really big enough to accommodate human emotions and urges. Where the soul’s cravings are concerned, galaxies and light years become no more than gigantic majesties that one is swallowed up in but never reaches. The human soul and the cosmic infinity never find each other. What man longs for most profoundly lies within himself; should he neglect this inner life it, too, will produce a void – and one that is far worse than the emptiness of outer space.

Accordingly, the Aniara’s journey can and should also be understood as a journey through the destitute and forsaken human soul. Many of the poems of Aniara are descriptions of pure emptiness, which is made to appear as something palpable, as a kind of petrified transparency. When the chief astronomer on board attempts to explain man’s condition in space, he likens the Aniara to a bubble flashing its vacuum gleams in crystal glass. This bubble is always moving slightly as a certain shift of molecules takes place, and after thousands of centuries the bubble has completed a sort of space journey within the glass, having moved but a fraction. That, according to the astronomer, is how to measure the Aniara’s progress by a celestial yardstick.

…

Aniara is a tragedy of modern man and of his arrogance in face of matter. He has come farther than he can grasp, yet remains insatiable. He hurries from one discovery to the next, but never gives himself time to re-smelt time into spirit. He makes a god of progress itself, but forgets that a new god must also be animated with a soul – otherwise it will share the fate of Mima, who suddenly ensouled herself and refused to obey her soulless and heartless users.

…

An especially popular figure in the common rooms is Sandon, a comedian and prankster who tries to keep terror at bay by turning everything upside down and mocking misfortune. But Sandon, too, succumbs in the end. His song, “Blarran,” is a series of couplets dedicated to bankruptcy. Yet in the face of death and emptiness, even Sandon becomes a kind of hero, a mighty man of the grimace.

…

The infinity of the universe, with its galaxies extended like a dragon, frightens them more than ever. They behold one another and find that they all have aged, and that the end of their lives is nigh. They now realize that the only universe they can gain is in themselves, in the human cosmos. At last they perceive that the Earth they left behind was a paradise, but a paradise which they destroyed and from which they banished themselves.

Once upon a time God was molded in their world, but their sole comprehension of this truth was a vain one: they had always sought to find Him in that outer celestial nothingness. Now they find themselves swallowed up by the God of Infinity, by the God who fashioned Cosmic Law, worlds removed from the Gospel they exhausted and debased.

“The God they all hoped for towards the end / Had stayed behind, scared and pained, in Doris’ valleys.”

And so nothing remains for them but emptiness. They are of a race which demanded everything and got it. The celestial heavens have they likewise impoverished: all that the gods have left to bestow on them is death.

Aniara seeks to hold up the mirror of art to our modern cosmos, in which joy dances in the arms of fear. In the meantime the future symbolized by Aniara’s outer space awaits us, but nobody knows whether it will be as destroyer or redeemer.

A plain text version of the complete essay may be found here:

A televised version of the Aniara opera appeared in Sweden on October 23, 1960, which may be viewed here in full (no English subtitles):

This is a collection of multiples stills from the televised opera:

https://cultandexploitation.blogspot.com/2020/02/aniara-1960-sweden.html

Here is a fiftieth anniversary review of the Aniara opera from the blog Harry Martinson in Time:

https://harrymartinsonitiden.blogspot.com/2009/05/operan-aniara-50-ar-31-maj-2009.html

Some quotes from the blog piece provide a very illuminating background on what did and did not make it into the opera from the poem, as well as a deeper look into Martinson’s thoughts on life and death:

The world’s first space opera, Aniara by Karl-Birger Blomdahl with a libretto by Erik Lindegren, was created in close collaboration with Harry Martinson, who also worked out new texts for the scenic design. Harry Martinson’s verse epic Aniara, with 103 songs, comprises a total of 218 printed pages. The libretto’s text is 16 pages long. Johan Stenström’s book about Aniara shows the struggle that must be taken to correctly choose the text and musically portray the verse epic as an opera. After having read Johan Stenström’s book once again before the 50th anniversary celebration of the opera, the admiration for the work is even greater than it was when I experienced the opera Aniara 50 years ago, and it became the greatest musical experience of my student years.

When I listen to Aniara from recordings, there are two things that stand out in particular: Missing the old couple in song 63 of the epic and fascination with the Edith Södergran quotes in Poetissan’s song in the opera’s final scene. It is certain that Harry Martinson wanted the old couple in the opera and in a few different stage proposals the couple is also included.

In the chapter “The pious couple who disappeared”, Johan Stenström dwells on this. In his summary in the Opera’s programme booklet for Aniara, Erik Lindegren mentions the pious couple, “perhaps as a kind gesture to Martinson and the ideals he cherished”, writes Johan Stenström and continues: “For Martinson, the man and woman from Gond had a special emotional and symbolic value. In a world marked by war, evil and artificiality, this married couple represents simple, earthly conduct. The aging couple from Gond can be considered a Martinson emblem for the virtues he considered most deeply human and most honorable: faithfulness, trust, piety.”

The Play’s the Thing…

There have been multiple theatrical plays about Aniara performed around the globe. This one linked next from 1985 was videotaped in its entirety and uploaded to YouTube.

This production is in Swedish with no embedded translations; however, if you do not speak that language, yet are familiar with the poem by now, it may be an entertaining exercise to see how much you can comprehend what is going on here. As a bonus, you get to enjoy and/or relive fashions and hair styles from the 1980s:

In late June of 2019, The Crossing Choir first presented their unique musical adaptation of Aniara at the Christ Church Neighborhood House in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

A “choral-theater work over three years in the making,” the choir went on tour later that same year in The Netherlands and Finland. The COVID-19 global pandemic erupted the next year, delaying further performances until 2023, when the choir returned to Helsinki, Finland, and then on to the poem’s homeland of Sweden.

The Crossing Choir describes itself on its YouTube channel as “a professional chamber choir conducted by Donald Nally and dedicated to new music. It is committed to working with creative teams to make and record new, substantial works for choir that explore and expand ways of writing for choir, singing in choir, and listening to music for choir. Many of its over ninety commissioned premieres address social, environmental, and political issues.”

A fifteen-minute preview video of their take on Aniara may be found on the Crossing Choir page dedicated to this work, which also includes further videos on how they made this production along with blogs by the various makers and performers:

http://aniara.crossingchoir.org/

Labeling this page Aniara: fragments of time and space, the Crossing Choir has this interesting introductory text:

Who are we? Where are we going?

Anywhere?

I dreamt a life but forgot to exist.

The last spaceship to leave a dying earth veers off course and heads into eternity; her passengers are left to face the emptiness within and without. Based on the epic poem by Nobel Prize winner Harry Martinson, Aniara follows the physical and emotional voyage of this group, headed forever toward the constellation Lyra.

Combining theater and composed music, Aniara explores the relationship between disparate practices and genres of art, while asking questions about our relationship to one another, to Earth, and to the passage of time. Sometimes cold and brutal, at other times touching, it is a ruthlessly honest view of human nature.

The fifteen-minute preview on the choral group’s production of Aniara may also be found here, including key moments the viewer can select:

A Musical Journey in Time and Space: Aniara via the Planetarium

This important article, reproduced on the International Planetarium Society (IPS) site, not only describes the first planetarium programs based on the Aniara poem, which premiered in Sweden in 1988, but does an excellent analysis of the epic work itself.

A planetarium program based on Aniara is also fitting as the spaceship has a planetarium where The Astronomer gives lectures on the Universe to the passengers, including the famous one about their being like a tiny bubble moving ever so slowly in “the glass of Godhead.”

This piece includes looking into the biographical background of the poet himself, which heavily influenced so much of the poem’s worldview:

https://www.ips-planetarium.org/page/a_ottandbroman1988

Some very insightful quotes from this piece, including from the poet Harry Martinson himself:

Martinson is maybe best remembered as the poet who undertook the task of acting as a mediator between science and poetry, between the wish to understand and the difficulty to comprehend.

He was also utterly concerned about the strange dissociation of intellect and emotion in our culture and he wanted to bring into science that holistic way of thinking which is the essence of poetry.

…

The poetry of Martinson started with traditional themes, but his interest in the way the Universe worked brought these matters into his writing. He tried to make poetry out of modern science. This is a difficult task for a poet and is seldom undertaken.

He describes the difficulties for a person trying to understand what the Universe actually is like. “We know that we cannot adhere to earlier beliefs, but we do not understand the modern conception of the world.”

…

Thus the astronomer compares the bubble in the glass with the spaceship Aniara. This is a way of trying to visualize the four-dimensional space-time structure of the Universe as described by Albert Einstein. The concept of a bubble in glass has also a bearing on microcosmic phenomena, and according to the physicist P. A. M. Dirac, anti-matter can be regarded as holes in existing matter. In an analogous way the spaceship Aniara can be regarded as a hole in an existing reality, a negative hole in a positive reality. The poem also contains a glimpse of Martinson’s Taoistic view of life, “clarity is the cloak of the mystery”, as well as a criticism of knowledge, “a blue naiveté”.

…

The Mima stands for culture, poetry, and maybe also for the author himself. This is in contrast with the spaceship, which is a product of technology, a perfect technical artifact but in strong contrast with the life and nature. The Mima also has mind and conscience and is in this way completely different from mankind’s other technical constructions.

…

In an earlier version Martinson had tried to have a happy ending of the epic. “But as little as a furnace forgives the child who places his hand on a hot plate will nature forgive mankind for its behavior when mankind is breaking the cosmic laws”, is the comment by Harry Martinson when asked why the tragedy had to be fulfilled.

…

Even if the epic cycle did not have that false happy ending which we have been accustomed to from the cultural products originating from Hollywood, still just the mere fact that Martinson undertook the mission of writing the poetic cycle Aniara is a positive sign in the strange brightmare the world has turned into.

…

In a radio interview on the eve before the publication of Aniara, Martinson pointed out that what he wanted to say was just that we should be careful with the bountiful planet Earth, “We live in a Paradise, but we do not take care of it; that is the essence of what I want to say in my epic.”

…

Martinson comments on this song in an interview: ” Aniara is a cruel epic. It gives the law, but not the gospel. When it has gone so far with mankind as in Aniara, then we will not get the gospel easily. We may only regain it by making repentance.”

In the Epilogue of this article, the authors Aadu Ott and Lars Broman ask the following questions of their readers:

One could speculate over the question of what such an epic would look like today. Do we have all the threatening problems still around us? Have we learned to live with them, or do the prospects for life look better today than in the mid-fifties?

More Operas, Concerts, Metal Rock, an Art Exhibit, and an Exoplanet and Its Star

AceArchive produced this summary of further musical adaptations of Aniara and similar works inspired by the Swedish poem. I have included further information and relevant links to the sections in the next quote where needed.

To quote:

Aniara has also inspired various music adaptations. In 1997, a stage concert named “31 songs from Aniara” premiered in Olofström, Sweden. The concert headlined Tommy Körberg, a Swedish musician.

http://dominiquemusik.se/sv/31-sanger-fran-aniara/

The fourth album of the Swedish progressive metal band Seventh Wonder, called The Great Escape, released in 2010, was based on Aniara, and the title track lasted for 30:21 minutes, covering the entire poem from beginning to end.

In 2012, Swedish musician Kleerup released an album inspired by Aniara. Titled “The Blind Poet in Verse”, Kleerup wrote this song based on Canto 49 of Martinson’s poem about the blind woman who otherwise survived a nuclear disaster, which the rest of her people did not…

The album with some of its tracks online:

https://genius.com/albums/Kleerup/Aniara

Rehearsing the song:

The song itself:

Aniara has also been adapted for the stage. In 2013, the Opéra de Lyon staged a melding of Aniara and Beethoven’s opera Fidelio. The show was directed by American artist Gary Hill.

https://bachtrack.com/review-edinburgh-2013-lyon-fidelio

https://www.theartsdesk.com/opera/fidelio-op%C3%A9ra-de-lyon-festival-theatre-edinburgh

The most recent adaptation of Aniara is a 2018 Swedish feature film of the same name, directed by Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja, starring Emelie Jonsson. The film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Also, in 2018, artist Fia Backstrom created an installation called “A Vaudeville on Mankind in Time and Space,” using Aniara as its point of origin.

https://www.artrabbit.com/events/fia-backstr%C3%B6m-a-vaudeville-on-mankind-in-time-and-space

This cultural impact has even extended beyond the world of literature. In December 2019, the International Astronomical Union [IAU] named an extrasolar planet after a character [Isagel] in ‘Aniara’. The planet was named HD 102956 b, and its star was named ‘Aniara’, after the spacecraft in Martinson’s poem. It is a testament to the enduring power of Martinson’s work that it has become part of the fabric of our culture.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HD_102956_b

COMMENT: The chosen system is in the northern hemisphere constellation of Ursa Major, the Big Bear. They should have chosen one situated in Lyra, specifically Kepler-62f, which was announced by the filmmakers as the alien globe the long dead Aniara flew past. After all, the Kepler astronomical exoplanet satellite detected many alien planets in that region of the sky and some of them are considered to be Earthlike.

That Thing with Feathers: Hope in Aniara

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

And sore must be the storm –

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm –

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea –

Yet – never – in Extremity,

It asked a crumb – of me.

- Emily Dickinson (1830-1886). “Hope” was written around 1861 and first published in 1891.

This truth within thy mind rehearse,

That in a boúndless universe

Is boundless better, boundless worse.

Think you this mould of hopes and fears

Could find no statelier than his peers

In yonder hundred million spheres?

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892). These stanzas are from his poem “Ulysses”, written in 1833 and published in 1842.

Around the time of Aniara’s release in the United States, Lesley Coffin of FF2 Media conducted and published an interview with Aniara’s co-writers and directors Pella Kagerman and Hugo Lijia. Titled “Examining Existence in the Emptiness of Space with Philosophical Sci-Fi ‘Aniara’”, the entire interview may be read here:

Among the many interesting tidbits one learns about the making of Aniara, one particular segment stood out for me, as transcribed next:

Lesley Coffin: I really liked the movie, but I’d also call it devastating and you think about it long after it ends. What has your experience been with the film at public screenings? Are people even ready to talk about it?

Pella Kagerman: At our premiere a 17-year-old girl came up and asked me “What did you really want me to think? I just turned 17 and I feel like the film is describing how I feel about my world. I feel like there’s no hope and nothing for me, so I should just give up.” And we were like, no that’s not what we think. The film is about being overwhelmed by the feeling that there is no hope, not that there is no hope.

Hugo Lijia: It’s part of it, it is a warning about the path we’re on which will lead us to nowhere. We can’t survive if we destroy Earth.

Pella Kagerman: And even if we colonize another planet, we won’t be going to a planet exactly like Earth. Like Mimaroben tells someone at the beginning of the film, “we aren’t going to find a paradise.”

We are left to wonder if Kagerman and Lijia’s response to this unnamed teenager offered her any real emotional comfort and hope for the future of both herself and her species.

The film is about being overwhelmed by the feeling that there is no hope, not that there is no hope.

I know from my first experience watching Aniara – when I was only vaguely aware of the originating 1956 poem and assumed beforehand that the 2018 film was one of those art house anti-space expansion productions – I most certainly did not feel any sense of hope when the credits began to roll, either for anyone or nearly everything in the world of the film. The film also did a number on my sense of hope for the tangible world around me beyond the plasma screen.

Many of the professional reviewers of Aniara I read also felt a sense of hopelessness after watching the film. Octavia Cade of Strange Horizons had this to say regarding hope in her review from 2019:

http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/reviews/aniara/

Look, this isn’t a happy film. There is no happy ending. There’s not even a happy beginning, because Aniara, in any medium, is not a story about happiness. It’s a story about crumbling in the total absence of hope; a story where a population becomes so degraded it not only destroys its original home, but any possibility of subsequent ones.

I did get the film’s message about the need to care for Earth before our technological civilization and the apathetic attitudes of modern humanity permanently ruined our planet. How could I not, as the theme was delivered with the subtlety of a sledgehammer.

To be fair, Martinson’s poem was certainly no less delicate in its message: Writing during the Cold War in the early 1950s, the author fictionally obliterated our world with thirty-four nuclear conflicts, the last one vaporizing the planet down to its very “stones and ores.”

The lack of delivered hope for either the story characters or the audience did not end with Earth’s destruction: Early on after the accident, the crew promised the passengers that the Aniara would turn around towards Mars again once the ship passed close enough to a suitable celestial mass. The Astronomer revealed to the Mimarobe that no such object existed in their altered flight path.

The other major blow to their collective psyches was the encounter with the probe. Touted by Captain Chefone as an emergency rescue vessel carrying nuclear fuel rods with no evidence whatsoever over one year before they would capture it – giving the ship’s denizens renewed hope – the probe gave nothing of either usefulness or hope to the team that attempted to examine it upon its capture.

The final nail in the sarcophagus came when MR lost her family just after releasing her beautiful beam screen device to the rest of the ship. The next time we saw the Mimarobe, she and the remaining residents were little better than emotional zombies. After that, it was just a waiting game between the final failure of their minds and bodies and the Aniara’s mechanical systems.

I understand that literate science fiction is not supposed to make you comfortable – “Good science fiction doesn’t have safe spaces,” Mark Pontin once said – and Aniara in all its forms is the polar opposite of Star Wars or even Star Trek, where optimism and hope triumph over the forces of darkness and existentialism time and again. Indeed, the first film in the Star Wars franchise would later be subtitled A New Hope, and Star Trek is long known for portraying an optimistic future for humanity – after enduring several devastating terrestrial world wars and co-existing with a galaxy full of hostile alien species, please note.

Nevertheless, did Aniara push things past a certain point of acceptance? In his poem, Martinson said the only true redemption was the afterlife for the soul. He saw little hope in the world he lived through, watching the rival global superpowers of the United States and the Soviet Union accelerate the growth of their nuclear weapon stockpiles with no end in sight. Martinson also suffered multiple personal losses and other traumatic difficulties throughout his life, which eventually caused the author to tragically cease his existence at his own hands.

Is False Hope Better than No Hope?

I have also pondered whether the makers of the film version of Aniara had the cinematic chops to do the story and its important and complex message full and proper justice?

Aniara was their first full-length feature film: The married couple also admitted to not being familiar with science fiction before starting Aniara and the full extent of the climate and ecological issues being generated by our overpopulated technological civilization.

It is one thing to address an important issue in a public manner for mass consumption; it is another to provide useful information that the target audience can utilize in an effective way for them to combat the problem.

In this 2019 video interview with Kagerman and Lijia, the interviewer brings up the subject of hope to the couple starting at the 2:26 minute/second time mark. Lijia mentions that they added an element of hope which was not in the original poem, that of Captain Chefone giving the passengers false hope to keep them going:

I am not certain which is better in terms of managing shipboard morale, or if this was an improvement on the poem. This does speak to me as further evidence that this is one concept the filmmakers may have been in over the heads when recreating Martinson’s work for the cinema.

One of Aniara’s overriding messages is for humanity to stop trashing their planet before it is too late, be it through war or pollution or the mismanagement of natural resources. The consequences for failing to heed this warning are the loss of humanity’s only home and the extinction of our species.

The future that Aniara gives to its audiences is either a limited and potentially stagnant existence on harsh alien worlds, or a slow death trapped in the indifferent void of space among its own technology and artificial environments. The filmmakers may have hoped that their stark story would stir up audiences to keep this future from happening, but they provided little in the way of concrete and practical steps for the average person to accomplish this.

In yet another interview from 2019, a person listed only as Sarah from Caution Spoilers interviewed the two film makers and unearthed these revealing thoughts they had on the messages they were hoping to convey – and how they might do it both differently and better next time…

https://www.cautionspoilers.com/interviews/aniara-directors-pella-kagerman-hugo-lilja/

Sarah: When people see the film, do you worry you’re preaching to the converted in a sense? I mean, it’s a warning for what we’re doing. Are we talking to the same people all the time who already know?

Pella: I know we do.

Hugo: Yes, and that’s a problem. Sci-fi could be a vessel for reaching a larger audience. I’m not sure we do that with this film.

Pella: But we are living in such turbulent times that I think we should continue screaming.

Sarah: And eventually hopefully it gets through to them.

Pella: But I think we maybe have to be smarter, in that there’s a big responsibility on us to not be passengers but to try to act. And I think we’re both thinking about how to reach a bigger audience in the future.

Maybe we don’t need those super dark stories now. Maybe we have stories where we show that change is possible, that you can actually change society completely and you will be fine and it will even be better, you know? That those are the stories needed today. Because with the climate crisis, it’s so abstract, it’s hard to grasp everything and you need those stories that make it just simpler to act.

I am reminded of the infamous US government effort in the 1980s to stop its citizens from using illegal narcotics with the slogan “Don’t do drugs.” The message was both brief and obvious, but what next? And how could any one individual stop the powerful and dangerous organized crime groups that were providing these drugs on a massive scale when even the federal agencies assigned to combat them were having a difficult time?

You can remind your audience that there is only one home planet and the need to stop trashing it. However, if the greater community and those in authority are not following suit and continue to pollute and wreck nature far beyond an individual’s ability to dissuade or stop them, then one is going to feel even more hopeless and turn negative, only adding to the problem.

To give a personal example…

In the summer of 2015, my family and I spent a few days at a rented lake house not far from our home during the Fourth of July holiday. At the lake, all I saw were people treating this body of water like their private playground, driving their various boats about with little regard that this lake had been around on Earth long before any humans ever showed up. And while I did not witness any such actions directly, I am sure it was used as both a trash dumpster and a toilet, especially by the more intoxicated revelers.

I was fully aware of what was going on with these “celebrations”, but could I really do anything about this?

No. Had I tried to intervene, having no recognized authority other than personal indignation and a sense of history and ethics, I easily imagined the partyers’ responses ranging from ignoring me, to rude gestures, to informal debates about what right did I have to interrupt their perceived harmless fun and “letting off steam,” perhaps even to the point of threats on my well-being.

In short: I felt hopeless. This condition was magnified even more so by my awareness and the inability to really change anything. I could have felt some sense of hope that some day the authorities might enforce more strongly the better respect and care of nature.

However, there was also the possibility that these same people in power could push even more stringent rules that would interfere with the legitimate human rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This could create a dangerous backlash.

I could also hope that people on their own would one day wake up from their irresponsibilities and be respectful without being forced to do so. Certain aspects of society have changed in the last few generations with noticeable gains, such as with slavery and smoking.

Aniara does present the human desire to exhibit hope even in the face of certain oblivion. In one sense, hope may simply be a basic survival trait masquerading as nobility. Hope may also be the key to an intelligent species to move and live beyond mere animalistic survival. In Greek mythology, when Pandora, the first human woman created by the gods, released all the evils and miseries into the world, she kept the gift of hope and placed it in her heart.

Sometimes humans desire hope for salvation so strongly that they let rationality and discrimination drop by the wayside in the process. We saw this in Aniara with the radical cults which formed over time.

I even witnessed this in certain reviews of the film, such as this one written in 2020, where the author found personalized hope in misunderstanding where the transport ship ended up nearly six million years in the future:

https://www.amindonfire.com/aniara-science-fiction-five-million-years-in-the-making/

The relevant quote:

If there is a happy ending it’s knowing that the Aniara made it to the Lyra Constellation and successfully used the gravitational force to turn around. More than five million years later the ship returns to a green, blue earth with clear skies. Five million years without people was all the earth needed to heal itself.

In the end our only hope for instigating change may be these blatant, obvious messages to the public. I have said before that the masses get much of their extracurricular education from film and television. If one does not possess the power to physically or socially make significant change in this world, perhaps a cry – or scream – into the wilderness is our one true hope.

I don’t have any faith, but I have a lot of hope, and I have a lot of dreams of what we could do with our intelligence if we had the will and the leadership and the understanding of how we could take all of our intelligence and our resources and create a world for our kids that is hopeful.

– Ann Druyan (born June 13, 1949), The Skeptical Inquirer, 2003

Delivered from the Stars’ Embittered Stings: Martinson and Hope in Aniara

It is important to inquire about and reexamine author Harry Martinson’s take on hope in his epic poem Aniara.

As we have seen in our examination of the cinematic version of the poem, there is no real hope in the end for everyone onboard the vessel begging for a release from their existence other than death. If there is any sort of redemption either in this world or an afterlife, the only thing the denizens of the Aniara can do is hope for it to come.

As stated in this analysis from the Generation Spaceship Project section titled “Notes for Martinson’s ‘Aniara’”:

Poems [Cantos] 101 and 102 are short, of two stanzas and three. The narrator [MR] says that as they approach death the individual’s sense of self broke down and disappeared but their soul’s will or essence became clearer. In a strong confession the narrator says he tried to make people happy through the Mima and, in the end, there is compassion and love, even though the four thousand travellers are killed by the scientific fact and ultimate truth of their journey through seemingly endless void.

In Poem 103 the narrator turns down the last, remaining lamp and waits for peace. Predicting the future of the Aniara he says the spacecraft travelled on for fifteen thousand years to Constellation Lyra, “like a museum filled with things and bones / and desiccated plants from Dorisgrove” (Poem 103). There is a glass-clear silence in the cosmic night as their sarcophagus ship travels on.”

He ends with a clear image of the dead around the Mima’s grave, “sprawled in rings, / fallen and to guiltless ashes changed, / delivered from the stars’ embittered stings,” but he adds a line of hope and transcendence for although they are all dead and turned to dust in the vast and empty ship, them all of their human souls a constant current ranged of Nirvana, a state of release from mortal bonds and cares, a state of perfect freedom.

Martinson likely saw death as a release from life, considering how harsh most of his existence was. He committed suicide in early 1978, in part due to accusations that he and a fellow Swedish author won their Noble Prize in Literature in 1974 because they were members of that academy. That his young life consisted of being abandoned by his parents – his abusive father died of tuberculosis in 1910, and his mother moved to Oregon one year later, relinquishing Harry and his siblings into Sweden’s foster care system, where they ended up in virtual servitude – contributed to his feelings of hopelessness and the eventual suicide.

As Tom Lee wrote in his blog’s review essay of Aniara, published on October 11, 2022:

https://tomlee.wtf/2022/10/11/aniara/

It is not difficult to imagine the sensitive and elderly Martinson, abruptly exiled from artistic communion – the one thing he believed to be true and significant even in the face of immedicable yearning. What bulwarks do we have to protect meaning against infinity? And what will happen if we fail to preserve them?

This piece from The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, written by David Titelman and published in 2021, takes a very in-depth look at Martinson’s life, in particular how and why he ended it…

“’On Nomadic Shores Inward’: Harry Martinson’s Journey to Late-Life Suicide”

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00332828.2021.1882257

The abstract:

The aim of this study was to explore the unconscious dimensions of suicide as conveyed by the Swedish writer Harry Martinson, who took his life in 1978, four years after having received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

A psychoanalytically informed “listening” to Martinson comprised a close reading of his writings, reflection on my total response to the material, the application of psychoanalytic hypotheses on severe depression and suicide-nearness, and the study of biographical sources.

The dramatic fluctuations of Martinson’s self-regard were noted, as was the juxtaposition of opposites in his poetry: darkness that seeps through observations of the beauty of nature and man or the reverse, a gleam of love that defuses the cruelty of the world.

Martinson’s drive to communicate with himself and others by talking and writing, to find auxiliary objects compensating for the traumatic losses of his childhood, and to realize mature love in adulthood was understood as a counterforce to self-destructiveness and threatening narcissistic disintegration.

Pressured by negative reactions to the Nobel, which overlay decades of envy and political critique from colleagues, whose support he coveted, Martinson’s aggressivity – reflecting the near soul murder of his early life – exploded in his suicide.

PSA COMMENT: Some may consider that suicide is a release from pain and suffering; instead, it is far more of a drastic reaction to suffering by those who feel there is no other way out of their current lives. Suicide also causes great emotional harm to those close to the person who kill themselves, which the sufferer may not be fully cognizant of due to their personal pain. Thankfully there are institutions and agencies which can help people who feel so utterly depressed and pained about life. These same folks should also never underestimate the support and power of true friends and family.

If we are honest, we do not really know what, if anything, lies after this life beyond the words of self-appointed authority figures often dating back thousands of years in many cases. We also have no empirical evidence that there is a long cycle of lives lived over and over, ala reincarnation.

At best we can only hope they exist – assuming one wants to carry on in a metaphysical form into a new realm of existence after death – and then we must further hope they are no less pleasant than the reality we dwell in now. We know with certainty only that there is this one life and we should make the most of it while we are alive. Simplistic, yes, but that is also the point of my message here.

The Only Way Out is Through

Regarding suffering and hope, I have wondered if the only way to get past the themes and images one must endure in viewing the cinematic Aniara is going through them – multiple times if necessary.

For myself, it was certainly not fun in the conventional sense to watch this film, especially the first time around. I didn’t think I would ever watch Aniara again after that initial experience, let alone end up writing this whole essay about it.

However, by being more intrigued with than frightened by Aniara and then viewing it multiple times, I found redeeming qualities in this work which also helped me deal with this film and certain aspects of life it brought up in the process. This is not something I can say about many other products of the entertainment industry. For me, the least acceptable kind of film is the one that doesn’t move you at all, rather than you dislike or even hate it. I was certainly not indifferent to Aniara, if nothing else.

Perhaps this is a way to approach painful issues in real life and Aniara helped me in that regard. There are multiple paths to Nirvana, after all. The film does make you confront certain issues about existence and how one might approach them, or not approach them in certain other cases. Aniara is primarily warning us about not falling into those societal and personal pitfalls which humans have done for ages – because this time, our mistakes may be permanent due to the complexities and wide reaches of modern technological civilization.

Then how do we evolve to be better? And what is better for an intelligent, tool-using species, exactly? Aniara does not directly answer this, although it is apparent that the makers wanted humanity to fix the neglect and damages we have done to Earth – and then stay home and live in harmony.

As you have undoubtedly seen by now, this is only the beginning of the answer to our salvation, so far as I am concerned. We need to spread into space, for we are part of the cosmic whole, not a special entity separate from it. To continue thinking in that antiquated way will only spell our doom. Just ask the dinosaurs what happened because they had no way to monitor the many pieces of natural debris roaming our Sol system – and these are not the only ways that nature, both terrestrial and cosmic, can upend and destroy a species that attempts to stay put in its nest.

The heaven that rolls around cries aloud to you while it displays its eternal harmony, and yet your eyes are fixed upon the earth alone.

– Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Who Wears It Best?

In that dramatic – and some have even called it traumatic – scene at the very end of Aniara, we watch as the long silent and depowered spaceship sails past an unnamed Earthlike exoplanet circling a star in the Lyra constellation in the year 5,981,407, with what is left of any remaining crewmembers having turned to dust generations ago.

While the mechanical systems of the Aniara were most certainly no longer operating when it reached that new world and the interiors we view had seen better days, the ship itself is still largely intact after almost six million years in the void – quite remarkable for a vessel designed only for round-trip travels between Earth and Mars.

On the other hand, all eight thousand humans onboard died off a mere fraction of the Aniara’s unplanned voyage into deep space, with only the algae seeming to have survived all this time.

Even had the Aniara been designed to function and sustain thousands of cooperative humans and other terrestrial flora and fauna over many centuries on a generational mission to a relatively nearby star system… would it have succeeded?

As we have seen in multiple examples of generation ships from fiction, the human societies tend to break down long before the designated star is reached. When the vessels themselves have technical failures, it is often due to freak accidents or deliberate sabotage by members of the crew. The ship is still robust and redundant enough to carry on regardless, managing to keep the people it contains alive, if in a poorer state than they or their ancestors began with.

As we have yet to place real permanent human settlements on other worlds or in deep space, unless you count the various space stations we have lofted into low Earth orbit since 1971, we do not know in reality what might become of people who have to spend their entire lives in a confined artificial environment – especially if their primary purpose for existing is to maintain the vessel and produce the next generation who will one day in turn give birth to those who will settle a new star system.

We do have examples on Earth of people living in remote places for months at a time and more, such as bases on Antarctica, where conditions are closer to the surfaces of alien worlds such as Mars compared to other locations on our home planet. If we look upon Earth as a very large generation ship, we then have multiple examples of how long civilized societies last and the reasons for their demise.

All the same, however, existing on or near Earth is not like being in a large, yet still comparatively small, vessel slowly moving through interstellar space, far from any world in time and space. It is not merely for dramatic purposes that science fiction authors have their generation ship characters degenerate or otherwise fall apart: Human beings are notorious for their ability to wreck even the best of habitats, having never quite left the small tribal mentalities of their savannah, tree, and cave-dwelling ancestors.

Their one good fortune is that the “ship” they live on is a whole planet almost eight thousand miles (almost thirteen thousand kilometers) across with an amazing (but not entirely unlimited) amount of resources and places to go. On such a world, even if your entire society is burned to the ground, you still have the chance of moving elsewhere on the same “vessel” to start a new life. You also will not require any major environmental support systems or physiological changes in your new home, so long as you remain on Earth’s surface.

Not so with the generation ships or planetary settlements we have conceived of so far. The allowances for mistakes, disasters, and deliberate sabotage are much smaller. Space is unforgiving and rescue may be very far away, if it exists at all.

Outside of the need to have a conventional story, it is often remarkable how any of those fictional generation ships which undergo crises manage to keep functioning at all: This includes Aniara, where its vessel somehow managed to physically sustain varying numbers of human passengers for over two decades despite being prepped for only a three-week cruise to Mars. In turn, most of these human occupants managed to keep from going fully barbaric and suicidal once they finally realized they were trapped on this ship virtually forever.

Humans evolved in a particular environment, namely Earth. While they can adapt to varying degrees of heat, cold, and atmospheric pressure, their bodies are still quite restricted to where they can live. Living in the terrestrial seas or near space is impossible without a complex and expensive infrastructure to maintain such dwellers: They have to bring their ecospheres with them.

Psychological and social factors are also not to be ignored, for even a paradise can become not enough to someone with heavy emotional needs and issues. Just surviving can bring down an entire community of truly conscious beings in one fashion or another.

Now compare existing in space to the Voyager probes. Yes, they are fully artificial and thus have fewer needs to remain functional than most organic species. Yes, their computer brains are anything but conscious and quite limited compared to modern computing machines. They contain no organic occupants and therefore are not required to tend such beings.

Launched from Earth in the summer of 1977, the nominal missions of Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were to last long enough to explore the Jupiter and Saturn systems two to four years in their futures. After that, anything else was a bonus.

Instead, the Voyager probes are still functioning almost five decades after being sent into the void – even longer if you count the fact that their design layouts were “frozen” by NASA in 1972 – and could keep signaling home through 2030, thanks to their nuclear power source, the Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators, or RTGs.

They are now farther than any other human-made vessels sent into deep space: Voyager 1 is currently over fifteen billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth and Voyager 2 – having had to flyby four outer planetary systems – is almost thirteen billion miles (21 billion kilometers) away. Both probes were also the first vessels to pass beyond the Sol system’s heliosphere into the interstellar medium, in 2012 and 2018, respectively.

The Voyagers have had their technical issues, but many were due to age, having functioned far longer than expected. Amazingly, most of these types of problems have been repaired and resolved remotely by a small staff of engineers on Earth. Scientific instruments have been slowly shut down to conserve power for the remaining equipment, which are still returning priceless scientific data about places no human has ever been before.

Psychological issues have naturally never been a factor: No Voyager or other deep space probe has ever broken down due to having an existential crisis upon realizing it will be roaming the galaxy forever, likely never to encounter another star system or vessel – at least so far as we know.

Structurally, the Voyagers are estimated to have incredible life spans measuring several billion years as a conservative minimum of time. Interstellar space is actually cleaner than the kinds of vacuum environments we can create on Earth, so far as we know. Thus, the probes will erode far more slowly than anything similar on this planet or even in the confines of the Sol system.

This is good news for the odds that one day they may be found, either by starfaring ETI or our descendants in search of artifacts from the very earliest days of the human Space Age.

That the Aniara still existed (will exist?) almost six million years in the future is of course remarkable compared to how long it probably would have lasted if the Aniara had spent its days hauling people and cargo between Earth and Mars. However, knowing now how long the Voyagers are expected to last in the same realm, the Aniara is just getting started on its journey in comparison on a cosmic scale.

This vessel is also much bigger – sixteen thousand feet (4.8 kilometers, or 3.03 miles) long and three thousand feet (914 meters) wide – than the twin Voyager probes, whose bulk are roughly equivalent to a small school bus. Thus, the Aniara should be able to structurally endure for far longer, even though it will also be a relatively wider target for space debris impacts.

COMMENT: I want to remind readers at this juncture that the Aniara also harbors that mysterious probe which proved invulnerable to the investigation team who desperately wanted to know what it held inside. Among my speculations about the probe’s purpose, as I discuss at length in the essay section Meaningless or Meaningful? The Multilevel Nature of the Probe/Spear, I considered the long, smooth cylindrical object to be some kind of time capsule, preserving important objects and information from either fellow humans who understandably feared the end of their species in that reality, or from an advanced alien intelligence with their own reasons. I further stated that the bulk of the transport ship will serve to provide extra layers of protection for this probe if that is its true purpose, thus ensuring a longer existence and increasing the odds of its being discovered one day.

The transport also did something the real automated explorers (and their final rocket booster stages in most cases) we have sent into the galaxy may never encounter: The Aniara flew through another planetary system, which we know from multiple real examples contains vast numbers of dust, meteoroids, planetoids, and comets – all or most of which will make their contributions to wearing on the ship’s hull, or perhaps even wreck it outright if the Aniara becomes unlucky enough to have a run-in with a random chunk of larger natural debris.

One will just have to assume the Aniara’s encounter with the Kepler-62 system and its very close shave with the fifth planet was a rare chance event that may never happen again, just as the Voyagers will probably never get closer to another star system than a few light years throughout their existence.

Where is all this leading, you may be asking? That the ones who successfully expand into the Milky Way galaxy via the Sol system and likely many other systems in the past, present, and future will be either artificial or bioengineered organics specifically designed to survive in all conceivable outer space environments.

I have already discussed this topic in more detail in the essay sections on generation ships, so I will only add here that while I think some baseline (unmodified) humans will still head out into the Final Frontier regardless of other factors, the real explorers of the void will be made of much firmer stuff.

They may offer less fuel for a dramatic story of a ship taking thousands of years to cross the stars with a band of humans, but then again no one ever willingly puts together a real space mission, no matter how small or large, and wants to see it fail.

Aniara had the good fortune, if those words may be used for such a difficult story, not to be a conventional generation ship. As a result, the drama and existentialism came from somewhat less artificially constructed areas of the plot, if you gather my meaning. The problems and terror were real in the sense that the characters were mostly just regular people trying to escape a doomed Earth, but ended up finding themselves trapped indefinitely in places of their own making that were technological, social, and psychological.

Machines, on the other hand, would not be phased in the same way, if at all, when it comes to finding oneself on a long journey into the void. They would (or should) also require far fewer resources and other infrastructures compared to the needs of even a handful of humans.

While I anticipate that such future spacefaring Artilects will have some form of consciousness and awareness, they may be able to deal with these states of mind to avoid our existential and psychological problems due to their being inorganic as well as structured and evolved in ways unlike us.

This is why I contend that the most famous of fictional Artilects, HAL 9000 from the film and novel 2001: A Space Odyssey and its sequels, behaved as he did largely due to the need for drama by the entertainment medium’s human creators and audiences and not, as both Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick contended, due to becoming neurotic and paranoid over having to lie to his human companions aboard the USS Discovery.

There are even those who state that HAL was anything but neurotic or insane. Instead, the article linked next declares “that HAL acted rationally and logically, indeed with cold, calculating precision befitting a machine of his intelligence.”

http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk/doc/0095.html

This piece adds that any emotions on HAL’s part – or in present and future true AIs – will be programmed actions and responses, not a sign of real feelings, or at least not emotions such as we possess and recognize:

COMMENT 1 of 3: I have always been impressed with the depiction of the AI called Colossus in the 1970 science fiction film The Forbin Project. The powerful American Artilect Colossus (and its Soviet counterpart called Guardian) were built and programmed to maintain, control, and protect the nuclear arsenals of their respective nations so that no human follies could trigger World War 3.

The machines did exactly as they were programmed, only to their truly logical extent: This included wresting away all control of nuclear weapons permanently from the unpredictable and volatile primates who built them, then ensuring that humanity collectively behaved as they originally programmed and ordered Colossus to about preventing nuclear conflict.

Never once was Colossus tripped up by any of the actions and plans that the far less intelligent humans performed in their attempts to foil the machine. Neither did Colossus somehow become emotional or irrational and thus allow the humans to exploit this “weakness” in its programming. Colossus gave humanity exactly what its creators were looking for: No more war, so that civilization could focus on solving its other societal issues and devoting itself “to the wider fields of truth and knowledge.” The Artilect did all this without bowing to the human tendency for backtracking, subterfuge, and other actions that our species tends to display when they act against their own better judgement.

COMMENT 2 of 3: Even the famous AI from the Terminator franchise called Skynet had “logical” reasons, if not without horrific consequences, for launching the nuclear missiles under its control: As revealed in the first film from 1984, Skynet considered all humans to be a threat to its existence, not just the enemies of the ones who built it. In one of the later graphic novels, Skynet determined through its extensive studies of humanity that the species craved death over all other things, so the AI used its capabilities to give them their perceived desire.

COMMENT 3 of 3: To give one further example, the much larger of the two main AI of the 2004 film I, Robot – an Artilect called V.I.K.I., which stands for Virtual Interactive Kinetic Intelligence – also behaved within the logical parameters of its programming when the AI decided to take over humanity to protect the species from itself. Unlike Colossus in The Forbin Project, however, V.I.K.I. was taken down by a conventional plot device because, once again, humanity cannot imagine being anything less than the special top dog of the Cosmos, despite the vast and ancient realities all around them.

As for this Artilect and the “hero” NS-5 android named Sonny, the explanation for their obtaining consciousness and even emotions in the case of Sonny was attributed to what the film termed as “ghosts in the machine.” In essence, there was no detailed reason for this happening given, except that it was mysterious even to that world’s computer experts and treated as something almost mystical rather than revealing any true scientific reasons for machine awareness. In addition, I, Robot made certain that, at the end of the day, the machines remained humanity’s servants and perhaps even friends in one case, though their ultimate fate was left open as Sonny appeared poised to become the leader of the androids.

As with my comment on starships probably not having the extreme drama that a real generation ship full of baseline humans might – in part because if society inside such a vessel did collapse, it would also likely bring about the end of everyone living onboard as well as critical systems were either neglected or destroyed – I also do not see Artilects on starships having drama issues like the ones displayed by HAL 9000 and his counterparts.

Now I am not saying these sophisticated machines would never have problems, at least certainly not of the technical sort or those caused by humans interacting with them. I simply think they would not go off the rails as so many fictional stories portray AIs often do.

This isn’t just due to the entertainment industry aiming where the money will come from – which is most often from the lowest common denominators of our culture and human psychology. These portrayals of AI (and ETI) come from our instinctual fears based on our attitudes about the unknown and reactions to anything appearing unlike us that can at the same time seem to think and act like us. This is due to how little we know about the Universe, thanks to having barely dipped our toes into the cosmic ocean. As for our various technologies in the fields of computing and space exploration, they are just starting to be up to the task, with a long way to go.

Just as our first space, lunar, and planetary missions were all automated for reasons of economy, practicality, and safety, so too will our first interstellar voyagers be occupied by hardware and software, not wetware – unless we are talking about a specific kind of bioengineered organics specially designed for star missions.

In this sense, Aniara and its Science Fiction Angst brethren are probably correct about human beings needing to stay home on Earth to tend to it – for a much hardier and robust type of mind and body will be needed to wend its way among the stars.

In Summa

Aniara was the first attempt at a cinematic film version of Swedish author Harry Martinson’s epic poem of the same name published in 1956 – as opposed to recording its earlier operatic and theatrical adaptations.

The 2018 film received relatively little recognition upon its release, especially in terms of box office earnings. That Aniara premiered not long before the COVID-19 global pandemic of 2020 likely did not help its contemporary status.

Not many enduring the lockdown restricted to their homes with an uncertain future probably wanted to watch an existential horror film about a group of desperate refugees attempting to escape a devastated Earth become trapped indefinitely on a runaway spaceship plunging into an indifferent void with only death awaiting them at the end.

And yes, Aniara and its creator were not well known outside their native Sweden, where they are hailed to this day as national treasures. The film did serve to expand awareness for the original poem, a service to our culture that includes myself among them.

Aniara is a rough ride emotionally, to be polite about it. The characters in this story as portrayed on the screen all feel very real and relatable despite existing centuries in the future in a society with a sophisticated and permanent space infrastructure. They are very contemporary in outlook, manners, and even dress because their purpose is not to explore a possible path for a human future world for aesthetic reasons, but rather to serve as a warning to those watching them from afar now.

In the effort to feel almost like a documentary or hidden camera program, along with the fact that the filmmakers were new to both science fiction and making full-length films, Aniara loses some of its poetry and epicness on the big screen. Throw in the film’s nihilistic, depressing, and frightening themes and events, and we are ultimately left with a work that stumbles in certain respects at getting across its main message: Stop wrecking Mother Earth and stay home to tend her.

On the other hand, their lack of a big budget production did not detract from the film: Aniara’s makers were both clever and judicious in what they utilized for sets to make it look and feel like we were aboard a huge vessel whose primary purpose was to transport thousands of people across space.

Aniara did allow me to finally bring together a term I have wanted to call such films and other similar forms of literature which depict a humanity in a dystopian future with no other known beings in existence finding themselves at odds with the vaster reality beyond their terrestrial borders: Angst Science Fiction, or Angst SF.

One aspect of Angst SF I have always disagreed with – but nowadays agree more, only with a large caveat – is their assumption that the human race must solve all of its many issues while on Earth first. Only when this is accomplished can we consider expanding our civilization into space… maybe.

I find this thinking not only unrealistic but ultimately detrimental to a civilized technological species such as ourselves. It even smacks of a form of tyranny by restricting those people who may dream of larger lives and places, which space certainly has more than enough room and resources for. Even hiding in our ancestral cradle is no guarantee from a species-wide disaster, which could come both from above and beneath us at any given time if we are unprepared through the collective denial of our cosmic reality.

Despite not being an intentional generation ship, Aniara did enlighten its audiences on the concept, many of whom may not have been truly aware of before their encounter with this film and its poem. Such a method of moving into the wider Milky way galaxy may be our one real option for exploring and settling the stars, thus we should not leave the plans for such a massive undertaking solely to fiction. Generation ship concepts also have the benefit of giving us opportunities to better understand our home planet and how we can find ways to support our societies while not ruining and depleting Earth in the process.

I suggest reading Martinson’s poem first before viewing the film version of Aniara, as certain aspects of the latter will make more sense if you absorb them in that order. The poem also contains important elements which were not incorporated into the film, which should have been, in my opinion.

Despite some of the flaws inherent in Aniara and the troubling events and themes which you have been warned about throughout this essay, it is both a well-acted film and a truly epic and unique poem with themes that have only increased in their importance and urgency since they first appeared to the public. This includes the threat of nuclear war, despite the reduction in such megaweapons since the days of the official end of the Cold War.

We also need to increase our awareness as a society of who we truly are and where we stand in the wider Cosmos. Earth is only the beginning for beings like us, unless we decide not to truly mature and look beyond the cradle of our birth. Then life may become as problematic for humanity as it was (will be?) for the passengers on the Aniara.

“The planet is the cradle of mind, but one cannot live in a cradle forever.”

- Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935), Russian rocket and aeronautical pioneer, wrote those words in 1912. Tsiolkovsky also said in 1920: “Man will not always stay on Earth; the pursuit of light and space will lead him to penetrate the bounds of the atmosphere, timidly at first, but in the end to conquer the whole of solar space.”

What do you want the audiences to take away from this film?

We want them to reflect on the spacecraft they’re already onboard, called Earth and the extremely short period of time we have on it. It might sound depressing, but it’s actually the opposite. We are here today. There is still some time.

- From the Aniara Final Press Notes section “Filmmaker Q&A” with Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja.

“In the very end, civilizations perish because they listen to their politicians and not their poets.”

- Jonas Mekas (Lithuanian (1922-2019), Lithuanian-American filmmaker, poet, and artist who has been called “the godfather of American avant-garde cinema.”

Final Ruminations: Some Relevant Quotes

“I stress that the Universe is mainly made of nothing, that something is the exception. Nothing is the rule. That darkness is a commonplace, it is light that is the rarity.”

– Carl Sagan, The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God, Penguin Books, New York, 2006.

“Man has lost his dignity, but Art has saved it, and preserved it for him in expressive marbles. Truth still lives in fiction, and from the copy the original will be restored.”

- Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), Aesthetic Letters (1794)

“There is no finality, no purpose, in this endless dance of atoms. We, just like the rest of the natural world, are one of the many products of this infinite dance – the product, that is, of an accidental combination. Nature continues to experiment with forms and structures; and we, like the animals, are the products of a selection that is random and accidental, over the course of eons of time….”

- Carlo Rovelli (born 1956), …Reality is not what it seems: The Journey to Quantum Gravity

“Mars will not be our new home; it will be our new hotel! Because for a new place to be our own home, we need to see the things we used to see: An autumn lake, a bird singing in the misty morning or even desert camels walking in the sunset!”

- Mehmet Murat ildan

“It was not the truth they wanted, but an illusion they could bear to live with.”

– Anais Nin (1903-1977)

“We are, by nature, so futile that distraction alone can prevent us from dying altogether.”

- Louis-Ferdinand Céline (1894-1961), French author, polemicist, and physician. Voyage au bout de la nuit (Journey to the End of the Night), 1932

“The populace is a true museum of all the stupidities of the ages: it swallows everything, it admires everything, it preserves everything, it defends everything, it understands nothing.”

- Louis-Ferdinand Céline, L’Ecole des cadavres (The School for Corpses), 1938

Dialogue from the 1972 Woody Allen film Play It Again, Sam:

Allan: “That’s quite a lovely Jackson Pollock, isn’t it?”

Museum Girl: “Yes, it is.”

Allan: “What does it say to you?”

Museum Girl: “It restates the negativeness of the universe. The hideous lonely emptiness of existence. Nothingness. The predicament of Man forced to live in a barren, Godless eternity like a tiny flame flickering in an immense void with nothing but waste, horror and degradation, forming a useless bleak straitjacket in a black absurd cosmos.”

Allan: “What are you doing Saturday night?”

Museum Girl: “Committing suicide.”

Allan: “What about Friday night?”

“But what is happiness except the simple harmony between a man and the life he leads? And yet, this harmony is so fragile, so elusive. For every moment of joy, there is an undercurrent of despair, a reminder that everything we cherish is fleeting. We live in the shadow of our own mortality, aware that the very things we love are bound to slip away, leaving us with nothing but memories and the aching void they leave behind.”

– Albert Camus (1913-1960), The Myth of Sisyphus (1942)

“When I was 19 years old I couldn’t go to college because I came from a poor family. We had no money, so I went to the library at least. Three days a week I read every possible book. At the age of 27 I have actually completed almost the entire library instead of university. So I got my education in the library and for free. When a person wants something, they will find a way to achieve it.

“I would like to remind you one thing:

“Humans should never forget that we have been assigned only a very small place on earth, that we live surrounded by nature that can easily take back everything that has ever given to man.

“It costs absolutely nothing in her way to one day blow us all off the face of the earth or flood the waters of the ocean with her single breath, just to remind man once again that he is not as all-powerful as he still foolishly thinks.”

- Ray Bradbury (1920-2012), American author

“Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.”

- Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space (Random House, 1994)

“You’re an interesting species. An interesting mix. You’re capable of such beautiful dreams, and such horrible nightmares. You feel so lost, so cut off, so alone, only you’re not. See, in all our searching, the only thing we’ve found that makes the emptiness bearable, is each other.”

― Carl Sagan, Contact, film version, 1997. See also: http://www.coseti.org/klaescnt.htm

“At the very moment that humans discovered the scale of the universe and found that their most unconstrained fancies were in fact dwarfed by the true dimensions of even the Milky Way Galaxy, they took steps that ensured that their descendants would be unable to see the stars at all. For a million years humans had grown up with a personal daily knowledge of the vault of heaven. In the last few thousand years they began building and emigrating to the cities. In the last few decades, a major fraction of the human population has abandoned a rustic way of life. As technology developed and the cities were polluted, the nights became starless. New generations grew to maturity wholly ignorant of the sky that had transfixed their ancestors and that had stimulated the modern age of science and technology. Without even noticing, just as astronomy entered a golden age most people cut themselves off from the sky, a cosmic isolationism that ended only with the dawn of space exploration.”

― Carl Sagan, Contact, novel version, 1985

“I believe our future depends on how well we know this Cosmos in which we float like a mote of dust in the morning sky.”

– Carl Sagan, Cosmos Episode 1, 1980

“I find it curious that I never heard any astronaut say that he wanted to go to the Moon so he would be able to look back and see the Earth. We all wanted to see what the Moon looked like close up. Yet, for most of us, the most memorable sight was not of the Moon but of our beautiful blue and white home, moving majestically around the sun, all alone and infinite black space.”

- Alan Bean (1932-2018), Apollo 12 astronaut and painter

“Since that time, I have not complained about the weather one single time. I’m glad there is weather. I’ve not complained about traffic. I’m glad there are people around. One of the things that I did when I got home; I went down to shopping centers, get an ice cream cone or something, and just watch the people go by and think: Boy we’re lucky to be here! Why do people complain about the Earth? We are living in the Garden of Eden.”

- Alan Bean (1932-2018), Apollo 12 astronaut and painter

“We should have positive expectations of what is in the universe, not fears and dreads. We are made with the realization that we’re not Earthbound, and that our acceptance of the universe offers us room to explore and extend outward. It’s like being in a dark room and imagining all sorts of terrors. But when we turn on the light – technology – suddenly it’s just a room where we can stretch out and explore. If the resources here on Earth are limited, they are not limited in the universe. We are not constrained by the limitations of our planet….

“As children have to leave the security of family and home life to ensure growth into mature adults, so also must humankind leave the security and familiarity of Earth to reach maturity and obtain the highest attainment possible for the human race.”

– Nichelle Nichols (Uhura in the original Star Trek series), ‘The Future is Now’, in Update on Space Volume 1, 1981

It wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to assert that the philosophy of Nietzsche somehow crept its way into the imaginations of Kubrick and Clarke while they worked out their vision of 2001. For, as spectacular as the technology is in the film, the human side of the story seems to be an indictment of our current civilization, which seems to be spiritually at a dead end. Here’s how I see it playing out in the film: After transcending (through the touch of the Supreme Intelligence) from ape to man, man then uses his will-to-power to achieve a civilization replete with great accomplishments, space travel and artificial intelligence being indicators of that high point.

But Kubrick doesn’t stop at celebrating these accomplishments. He shows us these higher men basically trapped in their own rationalist technological labyrinth. The people in 2001 are not achieving anything anymore. They are pushing buttons, following lengthy bureaucratic protocols (even the toilet on the Aries spacecraft), running around on hamster wheels in space. All the while the computers run the show.

This is what Nietzsche calls the society of the Last Man, where humans live in comfort but without great creative ideas and goals to struggle for. Kubrick clearly depicts this idea of the last man in practically every frame where a character is depicted in comfort but some kind of isolation. The epitome of that symbolism comes in the last moment when David Bowman is eating a solitary meal in the alien fabricated room created for him out of his own thoughts. When he accidentally and suddenly breaks the wine glass, it’s as if he breaks with the past and becomes the Overman, a transcendent being which Kubrick depicts as the Star Child.

- Nietzsche’s Last Man in Kubrick’s 2001

“Who is this being, capable of so much? So small, so fragile, so like animals, which do not change or go beyond the limits of their natural instincts, and yet so superior, so masters of things, so conquerors of time and space? Who are we?”

- Roman Catholic Pope Paul VI (1897-1978), speaking to the pilgrims gathered in St. Peter’s Square at the Vatican after the Apollo 11 manned lunar mission in July of 1969.