When I was first getting into the literature aspect of science fiction – after being inspired very early on in my life by the genre television programs and films of the day, among other sources such as comic books and toys – I came across an intriguing novel first printed in 1963 titled Orphans of the Sky by author Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988).

A reproduction of the cover for Heinlein’s SF novel Orphans of the Sky that I purchased in the distant mists of time – circa 1975. Here is where I first truly grasped the concept of a generation starship. Note how the vessel on this cover bears a strong resemblance to the classic Zeiss model of planetarium projectors.

A merger of a two-part story Heinlein had published in the magazine Astounding Science Fiction in 1941, Orphans of the Sky explored a concept then new to me: A huge vessel christened the Vanguard, five miles (8.04 kilometers) long and two thousand feet (609.6 meters) across, is designed, built, and launched to carry multiple generations of humans through interstellar space to the Proxima Centauri system, for there is no available means of propelling it at velocities near, at, or faster than the speed of light.

Decades after leaving the Sol system, the Vanguard generation ship and its original mission are disrupted during its long journey when a mutiny breaks out among the crew.

Most of the officers are killed in the effort to suppress the rebellion and the ship becomes divided into two main factions bordered off in different parts of the vessel. When there is no one left to control the Vanguard any longer, the ship drifts further into the galaxy away from its intended destination.

Over time, the descendants forget that they are on a deep space vessel and think their world is the entire universe. They have no real concept of their origins on Earth or what stars and planets are. What they do know about operating the various functions of the ship have become religious-style rituals overseen by chosen members who are still called by their original titles, but only as formalities.

You may read the entire novel here at a mere 79 pages (PDF format):

https://avalonlibrary.net/ebooks/Robert%20A.%20Heinlein%20-%20Orphans%20of%20the%20Sky.pdf

And also here:

https://metallicman.com/laoban4site/orphans-of-the-sky-full-text-by-robert-a-heinlein/

COMMENT: Since I first read Heinlein’s novel, I always wondered why there were neither windows nor electronic viewscreens for the occupants to look out from their ship at space: This might have kept them and future generations aware that their universe is much vaster than they ended up believing and retain the memories of their original mission plans.

Then again, the Aniara had lots of big windows and yet seeing the stars often brought about existential terror and bizarre cult reactions from many of the passengers. Of course, these people were only expecting a three-week luxury cruise from Earth to Mars, not an endless venture into the void.

In Orphans, there was at least one viewport available on the ship’s main bridge, but that area of the vessel was in dangerous territory occupied by the Mutie (Mutineers/Mutants) faction, off limits to the passengers, or Crew, living in the lower decks. Even the existence of the control bridge was considered only a legendry place by them.

Should humanity ever decide to venture into the Milky Way galaxy via generation ships, one hopes they will remember to install lots of exterior view windows on the vessels and keep better and more secure records of human knowledge and history available for all.

FUN FACT: Vanguard would become the name of the second American satellite to attain Earth orbit in March of 1958. The first of ultimately just three successful members of this satellite family, Vanguard 1 was also the first such vehicle to be powered by solar cells: This attribute kept the small satellite transmitting data until 1964. Vanguard 1 and its final booster stage are still circling our planet as the oldest verified human-made objects in space. They are not expected to fall out of their orbits until the late Twenty-Second Century.

For more information on Vanguard 1, which contains links to articles on other members of the Vanguard family, check out this detailed article here:

https://www.drewexmachina.com/2018/03/17/vanguard-1-the-little-satellite-that-could/

The idea of a group of people trapped in an artificial world which they have no idea is not the whole of existence has fascinated me for a long time. The concept also made me wonder if having to travel from one star system to another in this slow fashion would create the kind of social and educational problems that occurred in Orphans and the many similar stories that followed it.

The excellent Generation Spaceship (GS) Project, an in-depth study of interstellar crewed generation vessels as conceived in science fiction – which includes a detailed analysis of the poem version of Aniara – displays from this linked conference paper a quoted list of standard tropes on the subject that Orphans of the Sky helped to pioneer:

- The starship is huge and the passengers do not realise they are on a starship (Booker & Thomas, 2009, p. 42).

- The travellers have forgotten their original mission and lost their technological prowess.

- Strange ship-borne cults arise that threaten the mission.

- The flight crew become a distant technocratic elite while the rest degenerate.

- Powerful leaders arise from the passengers and overthrow or subvert the mission.

- Passengers escape into virtual worlds of cyberspace.

- The ship itself as an Artificial Intelligence (AI) turns against its passengers.

- The enormity of the distance and the isolation bring madness.

The passengers and crew of the Aniara never forgot that they were on a big ship traveling through space, nor why they were there – though many of them certainly wished they could have and tried to be elsewhere in every way available to them.

One of the “highlights” of Aniara were the numerous cults that cropped up once the denizens of the spaceship realized they were likely never going to see Mars or any other world in their lifetimes.

In the film these “space-borne cults” ranged from a fairly mild group that wanted back the slowly dimming light of Sol, to a cult begging Mother Earth, God, or the Universe (or perhaps all three or more) to forgive them for unmentioned sins (which perhaps included their species wrecking the home planet), to a society that said they worshipped the Mima upon its untimely passing. However, the Mima cult quickly devolved into an excuse for hedonism and yet another way for some of the ship’s passengers to temporarily forget their issues: A band-aid as opposed to a viable solution.

The poem possessed an additional cult that demanded (and received) human sacrifice. The closest the film version came to this extreme was the Mimarobe being made into a scapegoat for the loss of the Mima. Of course, none of these so-called religions were able to change their ultimate fate, except perhaps on individual levels within the ship.

I am curious as to why we didn’t see more adherents to mainstream religions, especially Christianity since most of the passengers came from Sweden. We do see the Chief Engineer wearing a silver crucifix during the probe examination scenes and making the Sign of the Cross at one point. In addition, during the early story scenes of the space lift transporting passengers to the Aniara stationed in Earth orbit, we witness the character we come to know as Chebeba holding an object tied to a dark string around her neck, appearing to be deep in prayer. However, her clenched hands conceal the actual identity of that object.

If there are any chapels, temples, or other sections on the Aniara dedicated to worship or even meditation and reflection, they are neither shown nor even mentioned.

If this imagined future era has relatively few adherents to traditional religions, that multiple radical cults would spring up so soon after the Aniara’s accident among a society of people who are otherwise considered educated and civilized says something powerful about the needs of human nature.

Included in this message is that society must feed the human soul, whatever you may wish to define it as, along with the body. It is deliberate that we saw the Aniara’s many material offerings to the passengers but nothing for their spiritual or psychological needs, perhaps except for the Mima – and that Artilect was quickly overwhelmed to self-destruction by so many suffocatingly desperate and pained minds.

Regarding the role of religion in stabilizing a generation starship community, refer to the upcoming essay section Religion as the Societal Glue? and its following subsections.

The officers of the Aniara did indeed become the overriding authority on the ship, with Captain Chefone as the self-chosen autocrat (he was an even more oppressive dictator in the poem).

At first, the ship’s officers tried to keep order for fear of how the eight thousand passengers might react once they realize their destination was to become endless space. Later on, it would become almost habit: Without a real plan to sustain the passengers and potentially improve their situation (recall how Chefone rejected MR’s initial offering to build the beam screen after the demise of Mima – whose overtaxed system he also previously ignored), merely keeping them alive and distracted was bound to eventually fail.

As for individual leaders rising up among the Aniara passengers during their journey, there were several folks who had their select influences such as Libidel, a rather intense and self-centered woman who created her own cult and named it after herself. The Astronomer brought her own influence on the passengers when she shared her knowledge about the true nature of the Cosmos, although revealing just how small and transient humanity is in the scheme of things often brought terror along with the enlightenment to her audiences. Even MR had a series of positive programs and effects throughout the ship. However, it cannot be said that any one individual was able to overthrow the ship’s crew, or if there were any serious intentions of mutiny or revolution among the passengers.

In contrast, the generation ship Vanguard in Orphans of the Sky experienced a violent mutiny led by an officer named Huff. His actions cost the lives of most of the experienced crew who knew how to operate the ship, sending the vessel off course. Subsequent generations considered the ship to be everything that existed and what little knowledge they retained of the past and the surrounding technology was treated religiously and performed through rituals without truly understanding what they were doing or why.

In regard to the Aniara passengers using virtual reality or similar technological methods to escape their dilemma, the closest they came to this was the Mima, which the MR described as “transport[ing] us back to Earth as it once was.” The second closest is the Aniara’s designated entertainment center, which includes various non-VR video games that look very much like relics from our time rather than centuries in the future, as might be expected.

There were no indications of personal VR headsets or their equivalent that passengers could use in the privacy of their staterooms. Printed books still exist; at least The Astronomer had some in her personal collection.

Even for their original three-week space journey, it would be expected on such a large vessel of the future with so many passengers that a wide variety of entertainment would be made available and not just a discotheque or bar.

As for “the ship itself as an Artificial Intelligence (AI)” turning against its passengers: There was no sign that any AI was integrated into the bridge or other key systems of the Aniara, at least nothing conscious. The only AI we encountered was the Mima, who was confined to one hall and originally designed to bring comfort and emotional escape to the traumatized refugees escaping a doomed Earth.

Although there was no form of attack or taking over ala HAL 9000, the Mima did turn on the passengers in the sense that she committed suicide from all their negative pressures rather than continue to be exposed to and tortured by their fears and nightmares as they sought relief from their emotional distress.

The Mima abandoned them when they needed her the most: Yet it is also understandable as the humans increasingly took from the Mima while offering her nothing in return but relentless grief. The majority of the crew and passengers saw the AI as little more than a tool for their use, rather than as a sentient and independent being. They let their ignorance and selfishness override MR’s continual warnings about the Mima needing time to recuperate. The result was the Mima seeing only one way out of her dilemma.

Even that drastic act only caused the passengers to focus on what they lost rather than who they lost and why. As a final insult to this injury, some members did attempt to honor the Mima for all she had given them – only for their memorial service to degrade into a self-serving orgy in the very place of her existence and eventual demise. They could not even maintain the integrity to pay a decent tribute to the Mima, let alone support her properly.

The parallels with humanity’s treatment of their home world, Earth, show that they had learned essentially nothing from what they had done to their native ecosystem. These people could not look outside themselves or accept existence as it truly is rather than how they wanted it to be, leading to their ultimate downfall.

The final bullet point from the GS Project cited paper, that “the enormity of the distance and the isolation bring madness,” can be considered the overriding theme of Aniara in all its iterations. Earth and Mars may be seen as spaceships in a sense, but they are too large as worlds for the human mind to think of as anything other than the whole of reality, except in the intellectual sense – and for most of humanity in both this fiction and our existence, they often remain willfully ignorant of the concept.

The Testing Grounds of Science Fiction

To compliment the resources of the Generation Spaceship Project, John I. Davies has an in-depth review of an important and relevant 2011 study titled The Generation Starship in Science Fiction: A Critical History, 1934-2001, written by Dr. Simone Caroti. The review may be read here:

Along with hyperlinks to further papers and information on the topic and its relevant fields, reviewer Davies notes the following major themes in this work:

- The conflict between the two conceptions of a WorldShip. Is it a world which happens have an artificial “substrate” or is it a ship with a mission which happens to require a multi-generation crew?

- How can the vision of dreamers like Tsiolkovsky, J. D. Bernal, and Robert Goddard be made to inspire the source civilization, for whom this is a massive enterprise, the initial travelers, their intermediate descendants, and those who must make a new world at journeys end?

- And, more practically, how can culture, science, and technology be sufficiently preserved over many generations?

Complete chapters of Dr. Caroti’s book may be read here:

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Generation_Starship_in_Science_Ficti.html?id=agkoCAAAQBAJ

Caroti also released an earlier paper that serves as a summarization of their later book. Titled “Theater of Memory against a Background of Stars: A Generation Starship Concept between Fiction and Reality” (CP1103, Space, Propulsion & Energy Sciences International Forum, SPESIF-2009, edited by G. A. Robertson):

https://www.astrosociology.org/Library/PDF/Caroti_SPESIF2009.pdf

The following text from the paper discusses an important aspect of a generation ship society that was also present in Aniara: The social hierarchy governing the residents of such vessels…

For this section of the paper is limited to an analysis of the governing body that should operate onboard the generation ship: would a democracy work best, or would it be more expedient to put the entire mission under the command of a “beneficent dictatorship” designed along the lines of, say, the government of the Greek city-states during the age of Pericles? Would a theocracy provide the necessary cultural cohesiveness, or would it degenerate into dogma and social sclerosis? Could different governments within the same vessel function as a generator of political and cultural energy?

An interesting feature of the “barbarism” approach is the deft sleight-of-hand with which most of the stories tend to dodge the issue of government. At the beginning of the voyage, the command structure of the generation ship is based on a hierarchy identical in every aspect to the power structures operating aboard any conventional vessel; there is a captain, a series of senior officers, specialists in various crucial disciplines, the crew – and their families, who often play the role of x-factor in the ship’s social mix.

Then order breaks down, usually through a freak accident [overpopulation in Wilcox (1940), a mutiny in Heinlein (1963), an epidemic in Aldiss (2000)], and the collective degrades into various kinds (and degrees) of pre-industrial societies, ruled by the kind of governing body that their Earth counterparts are known to have employed in ancient times: tribal and family-based collectives in Aldiss and Wilcox, an Aztec-type theocracy in Harrison, a quasi-feudal system in Heinlein, an oligarchy in Tubb (1976), and so on.

The whole point of these power structures is that they work (or do not) precisely because something went wrong; they make sense to the reader because he/she knows that the striking similarities with ancient Earth societies are the product of a reversal, of a turning away from the future and into the past.

By the time order and knowledge are restored the ship has reached its destination, so that the colonists can finally land and the issue of shipboard power structures is bypassed entirely – scant pickings for researchers seeking plausible answers to conceivable scenarios, and answering that there actually is a command structure operating onboard the ship before things go badly only dodges the issue. It is not beyond the realm of the possible to imagine that the kind of power structure that applies to Earth-based ships (an oil tanker, a cruise ship, a carrier battle group) would not work in the case of a multi-generational space voyage, essentially because such a structure is precisely designed not to be permanent – otherwise, the crew of a ship might end up thinking of their vessel as their country, and that could prompt them to set their own goals, in all likelihood at variance with the interests of the society that trained, paid, and equipped them. Earth-bound vessels are created to not be home.

However, such a choice would be impractical in the case of a generation ship, possibly to the point of being destructive, and one could argue that, instead of dodging the problem of shipboard governments, the collective of the reversal-to-barbarism stories provide a repeated commentary on the dangers of setting out on a generational trip without the proper social arrangement. Some tales in the group, however, do grapple with the issue directly.

One conclusion Caroti comes to regarding the success of a generation ship mission is the need for a new social arrangement such as a “shipboard ecological movement” rather than “exclusively placing our faith in self-denial and dedication to the cause to successfully see the mission through.”

Today, at the birth of the twenty-first century and possibly at the threshold of what Kurzweil (2000 and 2006) in his books The Age of Spiritual Machines and The Singularity Is Near calls the “post-human singularity,” humans face the prospect of a radical change not only in our infrastructure, but in our bodies as well.

Nanotechnology, stem cell research, genetic engineering, cloning, cybernetic interfaces – all these advances seem to be lying in wait immediately outside of our present reach, not yet obtained but very close to becoming real. In the meantime, however, we do what we can with what we have: ourselves, slightly improved and longer-lived than we were millennia ago, but basically still the same system, and it is here that the speculations of golden-age SF might yet become, fifty years after the fact, actual.

When taken together as an interconnected, thirty-year-long dialogue on the subject, the group of stories featured in this paper essentially represent the attempt to find out what happens when whole generations of un-augmented, standard-lived human beings are asked to spend their entire lives in the service of a goal they will never reach. From the evidence gathered, we should probably conclude that exclusively placing our faith in self-denial and dedication to the cause to successfully see the mission through would be a mistake.

Sociologically as well as psychologically, we will need a radically new social arrangement to make the prospect of a generation-ship voyage bearable for the people onboard, and in this respect the development of a shipboard ecological movement may well prove to be the most important legacy of the stories under examination.

The author also addresses another issue prominent with the characters in Aniara: Their response to the darkness and space-time depth of the seemingly infinite Universe:

…let us not forget that human beings are still wired to respond to darkness with fear, and that the color black carries a set of associations which, in the long run, could easily have an adverse effect on the crew’s morale, even on their sanity. There would be plenty of time for that in a generational flight. The obvious solution to the dangers inherent in contemplating the void would be to close all the viewing ports, but that would generate another problem, something with which the crews of today’s submarines are fairly familiar: claustrophobia.

COMMENT: Having no viewports with which to see the stars through is a large part of what brought about the situation aboard the Vanguard generation ship in Heinlein’s Orphans of the Sky. Unable to observe outside their vessel, the future members of the Crew end up thinking that the Ship was the whole of reality. The Stars became mysterious objects lost to legend and mythology. Their original celestial destination, the Proxima Centauri system, was warped into the phrase “taking the Trip to Far Centaurus”, which meant passing into an ambiguous afterlife after one’s physical death aboard the Ship.

Having extensively studied the many scenarios of fictional generation ship stories and the cases of real isolation by various groups of people throughout history into modern times, Caroti strongly suggests that mission designers focus on the happiness of all those who will be taking the journey to another star system. Otherwise, all the technological advancements and distractions will ultimately fail in the face of whether the crew feels fulfilled in their life purposes or not – just like what happens with people far too often on Earth.

However, it could be argued that, since one of the key variables in a generation ship voyage will be the crew’s happiness with their situation, the future organizers of such a mission will find themselves in the position of having to literally plan for happiness.

This cannot be the happiness of, say, an aircraft carrier’s crew, who knows they will be back home soon enough and can therefore bear the discomfort of their relative isolation for the time being. There is no “back home” for a generation starship.

The awareness of the fact that they are, for all intents and purposes, a world of their own, humanity’s first extraterrestrial planetary colony, must be met with curiosity, eagerness, even enthusiasm. The people onboard must necessarily embrace the idea that, far from venturing out into space to perpetuate Earth-bound realities on other planets, they are in fact letting the realities of deep space change them.

Any other attitude will probably engender feelings of isolation in a hostile universe, feelings which will accumulate inside every individual on the ship over the years, and eventually find collective expression in the form of some kind of social collapse – possibly similar, or even identical, to the barbarism approach.

If radical change is the way to successfully plan and execute a generational mission, then knowledge in all its aspects must be fostered, practiced, and constantly updated. The price of doing otherwise would be uncontrolled, undirected change that would rob the ship’s population of choice and purpose, and would probably result in irreparable damage to the mission itself.

Knowledge would give the shipboard society the ability to assess, extrapolate, and normalize change, to adapt to altered circumstances without losing too much of its constituent characteristics in a single stroke.

The next section delves further into how a generation ship mission might be a success and offers another solution to the Caroti happiness factor.

Coping with the Infinite

How does one go about designing a successful generation starship mission that could last centuries or more? By successful, I am not just referring to all the technical issues involved in keeping hundreds to perhaps thousands or more humans alive and safe for multiple lifetimes through an environment quite hostile to Earth life.

The psychological and social needs of these pioneering folks will play a huge role in whether such a voyage attains its goal with a healthy crew, or if we end up with the dystopian mess that such science fiction loves to play with for its obvious dramatic richness.

First let us assume the following scenarios:

- Humanity has not found a way to move through space at high relativistic speeds or break the light barrier.

- It is not technically feasible (or desirable) to put the passengers in suspended animation such as cryogenic freezing.

- Humanity needs to escape the Sol system for any variety of threats to our species and our civilization. As a result, and assuming this happens relatively soon, we need to leave “as we are” physiologically, rather than wait for any bioengineered improvements to better adapt us to a long interstellar journey, or even download our minds into some advanced technological infrastructure.

- Perhaps rather than a huge crisis as motivation, an organization wants to travel to another star system leaving in the state they are currently dwelling in and do the same for their future generations. Reasons for this could include religious and cultural freedoms, a huge motivator in human history for a group of like-minded people wanting to migrate elsewhere.

As has been noted numerous times in this essay, many if not most of the people inhabiting the Aniara had a certain amount of material wealth both in terms of monetary value and the quantity of their possessions. However, they seemed to lack a strong sense of spirituality or even religion.

When confronted with the ancient vastness of the Universe beyond their small portions of humanity’s home world once their lives were permanently relegated to deep space, their civilized coverings soon fell apart. One very obvious sign of this change was witnessing those passengers who may have never been religious or spiritual before in their lives suddenly become fervent devotees of what would been called nothing less than a cult back on Earth in less drastic times.

Their naked fears led the Aniara denizens to behave in ways they might never have considered otherwise, once they no longer had the warm, comforting embrace of Mother Earth and the perceived protective trappings of their own civilization.

These cults gave the passengers the emotional and psychological fulfillments they were craving after the loss of their planet (or planets, if you count Mars along with Earth) and the veneer of security from a technological society, although they were temporary fixes at best.

Even The Astronomer, who eschewed religion and supernatural causes in any form (recall her discussion about the terms “miracle” and “chance” meaning the same thing), excessively turned to the bottle (alcohol) for solace. Her intelligence and scientific knowledge were not enough: Indeed, her educated perspective on the real makeup of the Cosmos paradoxically contributed to her baser fears at the emptiness and indifference of existence so far as she knew it.

As we know all too well by now, the crew and passengers of the Aniara were not prepared for their altered journey through space, either psychologically or materially. Thus, they grasped at whatever looked like a solution, whether it truly was one or not. If nothing else, their actions and reactions showed what humans require the most when life has been reduced to its essences: Food and water are but part of the full equation for long-term sustainability.

Religion as the Societal Glue?

Working on the possibility that our first crewed starships will be generation vessels comprised of humans who are not radically modified for long deep space endurance – and with the option of having either a target star system in mind for settlement or utilizing multiple planetary systems for resupply and such, making all of interstellar space their permanent home – what will keep these brave people together and civilized so they can achieve their predetermined destinations?

In 1999, astronomer Steve Kilston (born 1944) first presented his plan for a generation ship called The Ultimate Project to the Stars as well as the “Plausible Path to the Stars”. The latter name was described in a paper co-authored with Ed Friedman titled “Space – How Far We Have Come, How Far There Is to Go”, published in the Proceedings of the IEEE, Volume 88, Number 3, March 2000. I also wrote about this project for Centauri Dreams in 2008.

Kilston and cohorts Sven U. and Nancy J. Grenander imagined a very long-term program: A “cylindrical starship over one mile long and one-mile-wide weighing 100 million tons that would carry one million people across interstellar space for 10,000 years or more.” Shielded from cosmic rays by a surrounding layer of water in its hull, the primary mission goal of The Ultimate Project vessel is to find and settle an Earthlike exoplanet.

This Ultimate Project would also take a long time to come together (Kilston estimates half a millennium), move at the relatively safe speed of 373 miles per second (0.2 percent of light speed), and cost an absurd amount of money (fifty trillion US dollars). The plan also contains a one-hundred-year shakedown cruise through the Sol system before departing for a suitable nearby star system.

What would keep these one million passengers and their descendants together and on course in multiple senses of the word over the next one hundred centuries of their space voyage? According to Sven U. Grenander, the manager of the formation and start-up of The Ultimate Project, sees a written constitution as the key to avoiding the “factionalism and barbarism” that he sees as a certainty aboard the generation ship otherwise.

“The constitution has to serve as a fractal seed that can grow in a predictably orderly fashion and not be overtaken by chaos or lawlessness,” says Grenander. “The constitution is the most important element of the project as it is the only thing that will keep the human crew from spiraling off into any number of project-defeating directions.”

Is a written set of laws enough to keep a society of people isolated from their home world and the rest of the galaxy for ten thousand years both civilized and focused on the original mission goals?

As I write this, we are watching the Constitution of the United States, a body of laws ratified a mere 236 years ago, being questioned and tested in ways unlike anything since the days of its being formed. Combine this with the average lifespan of most civilizations on Earth since the first ones formed roughly six thousand years ago, and it is only wise to ponder the strength and longevity of a set of rules laid down in what will one day become the distant past for a select group of people. With all due respect to the U.S. Constitution and Sven U. Grenander, please note.

To read the full IEEE paper authored by Kilston and Friedman, see here:

https://www.academia.edu/92984029/Space_how_far_we_have_come_how_far_there_is_to_go

To read my Centauri Dreams essay on The Ultimate Project, go to this link here:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2008/06/18/the-ultimate-project-to-the-stars/

While The Ultimate Project is likely to be ultimately just an exercise in planning such journeys into the Milky Way galaxy, it does make some very good analogies to other long-term efforts by humanity that ultimately bore fruit. Specifically, the building of cathedrals during the European Middle Ages by the Roman Catholic Church.

These massive churches took centuries to complete. That these cathedrals happened at all was due to the fact that they were supported and funded by a powerful religious institution, which was often as much political as it was about spirituality.

This fascinating article from Centauri Dreams by Andreas M. Hein (born 1981) delves into what it took to produce cathedrals across Europe throughout the centuries as parallels to having other long-term projects such as generation starships:

The key here is that these cathedrals became reality due to their spawning and support from a religion and its own long-lasting infrastructure. The tenants of religion can inspire people in ways that other institutions often fall short on. While this is certainly not the only answer, human history has shown it is among the more enduring aspects of our society, however modern cultures may hold their views on God, the supernatural realm, and spirituality compared to how our ancestors once did.

Communities of the devout such as Roman Catholic monks spent centuries preserving ancient texts by copying and recopying them by hand in the era before the printing press that otherwise might have been lost to history. Their focus on a common cause and purpose they saw as essential beyond their own needs played no small role in the success of their work and society.

The Atomic Priesthood

In the masterpiece 1959 science fiction novel A Canticle for Leibowitz by author Walter M. Miller, Jr. (1923-1996), an order of Cistercian monks keeps the surviving remnants of human knowledge preserved for several thousand years after a global nuclear war in the late Twentieth Century and a following purge by the survivors destroys most of civilization. This is a parallel to what their medieval brethren did throughout the Middle Ages after the fall of the western Roman Empire in the late Fifth Century CE.

As I was researching certain details about Canticle, I came across this paper from 2016: “The Atomic Priesthood and Nuclear Waste Management: Religion, Sci-fi Literature and the End of Our Civilization” by Sebastian Much.

Originally published in Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, Volume 51, Issue 3 (2016), on pages 626-639, the following abstract describes a plan for a nominal religious order that would maintain knowledge about the inherent dangers from nuclear waste storage facilities for adaptation to future generations over the next ten thousand years:

This article discusses the idea of an “Atomic Priesthood,” a religious caste that would preserve and transmit the knowledge of nuclear waste management for future generations. In 1981, the US Department of Energy commissioned a “Human Interference Task Force” (HITF) that would examine the possibilities of how to maintain the security of nuclear waste storage sites for 10,000 years, a period during which our civilization would likely perish, but the dangerous nature of nuclear waste would persist. One option that was discussed was the establishment of an “atomic priesthood,” an idea that science fiction writers like Isaac Asimov and Arsen Darney had already toyed with. Reading the HITF report alongside sci-fi novels, my article will shed light on the question of how the sheer force of nuclear power (and the longevity of nuclear waste) lends itself to religious interpretations and how the idea of the atomic priesthood is connected with the utopian/dystopian aspects of nuclear power.

You may read the full article here:

Free to Be Me: The LDSS Nauvoo

In the past, I have stated on various media platforms that the first humans to actively depart the Sol system for the wider galaxy will be members of a religious order or cult, including a personality cult following a charismatic leader or group of leaders.

There is some precedence for this:

- The Biosphere II facility in Arizona was originally designed by a wealthy individual to facilitate he and his followers eventually living permanently on the planet Mars.

- Drug “guru” Dr. Timothy Leary (1920-1996) met with Cornell astronomers Carl Sagan (1934-1996) and Frank Drake (1930-2022) in 1974 while the former Harvard professor was in prison on drug possession charges to ask how he and a select group of three hundred devout followers might be able to settle in another star system to live their lives in freedom from terrestrial restrictions.

- The two scientists had to explain to Leary how crewed interstellar travel just was not possible for their foreseeable future. Leary later rejected their rejection, yet he and his sycophants never left Earth just the same.

The excellent hard science fiction television series The Expanse, which aired for six seasons from 2015 to 2022 and takes place in the middle of the Twenty-Fourth Century with human civilization having spread through most of the Sol system, introduced viewers to the LDSS Nauvoo: A generation ship being built for thousands of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, also known as the Mormons.

The Mormons want to settle in the Tau Ceti system, located twelve light years from Sol. Their desire to move is based on the fact that this future society has serious restrictions on birth control (Earth alone harbors over thirty billion humans, many of whom appear to live in poverty) and this conflicts with their doctrine.

Societal prejudices of the Church being an organized religion in itself is another potential factor for these Mormons to want to live beyond the reach of most of humanity – a bias their founding ancestors encountered in Nineteenth Century United States, forcing them to move further westward to escape persecution.

ASTRONOMY LESSON TIME 1 of 2: Although Tau Ceti is a real star similar to Sol (spectral type G8V) and appears to have at least four exoplanets, all Super Earth types, with at least two of them orbiting this smaller singular yellow dwarf sun in its habitable zone, our interstellar neighbor is a problematic star system in terms of habitability: Astronomers have determined that Tau Ceti is surrounded by ten times the amount of cometary and planetoid debris that the Sol system possesses. This means that the exoplanets of this system have much higher chances of being bombarded by these abundant system formation leftovers.

On the other hand, if the residents of the Nauvoo want to remain aboard their ship and simply utilize the plentiful natural resources around Tau Ceti, this would certainly improve their chances for an extended survival. They would even have the option of moving on to other stars and their accompanying worlds.

This article by Neil Levyis, “a senior research fellow of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and professor of philosophy at Macquarie University in Sydney”, looks at the pros and cons of such a plan:

https://aeon.co/ideas/would-it-be-immoral-to-send-out-a-generation-starship

This quote from the piece sums things up rather well, pointing out the parallels to living on the spaceship we call Earth:

Whether generation ships would be ethically permissible, despite locking children into a project and way of life that they didn’t choose, seems to depend on whether the goal – say, the survival of the species – is itself sufficiently valuable to justify it. That’s not a question I will attempt to answer. Given that generation ships remain a long way off, it’s not a pressing concern. But at different scales and in different forms, most children on Earth today were born into constrained futures, whether through poverty, religious beliefs or impending environmental degradation. Asking about the permissibility of generation ships might give us a fresh perspective on the permissibility of the constraints we impose now on human lives, here on the biggest generation ship of them all – our planet.

This second piece quote hits home even more succinctly:

The differences between Earth and generation ships are differences in scale, not in kind.

Looking further at Earth as a spaceship, this essay shows how the label is more than just a clever comment:

https://www.space.com/earth-iss-sustainable-living-world-space-week

To quote:

Imagine living in a place where your survival depends upon living within your limits, not consuming more food and energy than you produce, creating enough fresh water and air to live on, reducing waste to a bare minimum, recycling everything that you can, and avoiding contaminating the environment around you. This is what astronauts must face, to an extent, on board the International Space Station, and what they would have to face to a greater extent in future settlements on the moon or Mars.

But it’s also how we have to live on Earth if we are to protect our environment, which is one of the themes of this year’s World Space Week, running between Oct. 4 to Oct. 10. [2024].

A space station, or a lunar base, is largely a closed-loop system. What we mean by this is that it must produce its own resources and then recycle them, feeding them back into the system because they are limited. Consume too much, and astronauts might run out of air, food, water or energy, which could be fatal. Sure, there are occasional resupplies from Earth, however, so they are not 100% closed loop systems. What is a completely closed loop, however, is Earth itself.

This paper asks how large a generation ship would have to be to accommodate a mere five hundred human beings on an interstellar voyage:

ASTRONOMY LESSON TIME 2 of 2: Tau Ceti was the first of two stars examined by the first modern era Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) effort called Project Ozma. Using a radio telescope at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Green Bank, West Virginia, astronomer Frank Drake spent roughly two hundred hours in 1960 listening for any signals of an artificial and alien nature emanating from Tau Ceti and Epsilon Eridani, without success.

This news item from 2017 on the Nauvoo further highlights the arguments in favor of a religious group making a very long space journey a success. The relevant quoted items which follow come from this link:

Authors Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck – who are writing “The Expanse” books under the pseudonym James S. A. Corey and are also writers/producers on the TV series – created a tomorrow in which humans have colonized the solar system, but have no faster-than-light ships. For the purpose of their narrative, they needed a huge ship that would carry a large number of people to a distant solar system – a journey that will take more than a century.

“We wanted to have a generation ship,” Abraham said. “We wanted to have this huge, ambitious, expensive, difficult, dangerous project. We looked around and talked about who would be most likely to get behind something like that.”

They discarded the idea that a government would build such a ship, “because it doesn’t get you any votes,” Franck said. “And I can’t picture a corporation doing it, because there’s no money in it.”

So they kicked around the notion of a religious group undertaking such a project because of “that sort of unity of purpose that’s necessary to invest so much time and energy and treasure into a single project with an uncertain outcome,” Franck said.

The more they thought about it, the more the idea of involving Mormons made sense. Abraham pointed to the Mormons’ trek west to settle the inhospitable Utah desert.

“Neither of us is Mormon,” he said. “But we’ve had enough experience with that faith to see that, yeah, the idea of a journey being baked into the religion, and the kind of underlying sense of radical optimism you’d have to have to undertake something like that seemed like a good fit.”

And Franck came upon news about the construction of City Creek – including that the complex in the heart of Salt Lake City had a $2 billion price tag.

“I was, like, ‘Here’s a group that will drop a couple billion dollars to just have more shopping for people who come to visit the temple,’” Franck said. “And I thought, ‘Well, if you’re building a trillion-dollar spaceship 300 years in the future, who’s going to have the money and the institutional will to do that? It’s the Mormons.’”

For more technical information on the Nauvoo – the series excels at sticking to realistic physics and technology more often than many other science fiction entertainments – see this following article:

The makers of The Expanse even delved into the physics of rotating a giant vessel with a “radius of 0.25 kilometers [0.155 mile] and a length of 2 km [1.24 miles]” here:

https://www.wired.com/story/the-physics-of-a-spinning-spacecraft-in-the-expanse/

Here is a video overview of the Nauvoo:

Here is a fandom background and history of the Nauvoo, where we learn that “the vessel measures 2,460 meters long, with a width of 960 meters,” possesses roughly “a hundred million tons of steel,” and can carry at least seven thousand people onboard, though this number applies to the Nauvoo’s post-generation ship refitting.

https://expanse.fandom.com/wiki/Nauvoo_(TV)

Getting into the Details: Technical Issues with the Aniara

The Aniara became an inadvertent generation ship after an errant collision with some space junk forced her crew to eject the vessel’s radioactive nuclear fuel rods, leaving the Aniara without a means to either propel or maneuver itself. Thankfully, if that is the word which can be used here, the Aniara has an alternate power source to keep the rest of the ship systems operating: This includes the processing of algae into both food and oxygen.

The Aniara continues to function for years after missing its three-week rendezvous with Mars and sails off into deep space. Despite many of the eight thousand passengers meeting their demise through accidents, incidents, and suicides, there are still enough people left who are able to survive – if not actually live – on the ship into the second decade of its journey.

By now it should be apparent to you, dear readers, that the Aniara is really an analogy for early Twenty-First Century climate change Earth in the 2018 film and the Cold War era Earth in the 1956 poem. The vessel’s numerous passengers are of course contemporary versions of the same hominin species that has abused and otherwise failed to truly appreciate and respect the spaceship they are all riding and living upon.

As for the original author of this work, Harry Martinson was inspired to write and publish the first twenty-nine cantos of his epic poem after viewing a particularly sharp and shining visage of the Andromeda galaxy (also known as Messier 31 and NGC 224), our nearest fellow spiral galaxy to the Milky Way at 2.5 million light years, with his personal telescope one night in 1953.

AN OBSERVATION: Martinson must have encountered what astronomers would call a very favorable evening of “seeing”, with clear skies and little atmospheric turbulence. This celestial event which inspired Martinson to write such a great piece of literature is also why we cannot let our growing civilization take away the stars through the artificial problem of light pollution. If we cannot see the stars from Earth, eventually we will not bother to reach for them.

Despite the epiphany and motivation from witnessing a real cosmic island of suns with his own eyes, plus his later excursions into other areas of astronomy and science, Martinson became fearful and despondent as he mentally explored further into space. Taking a tack different from the growing enthusiasm of the 1950s for space science, technology, and exploration as humanity’s Manifest Destiny and salvation, Martinson used space and contemporary events such as the Soviet Union detonating their first hydrogen bomb as an allegory for our lives being doomed by our own actions.

It is apparent that Martinson was being quite poetic in multiple senses of the word when it came to his depiction of life aboard a doomed spaceship plunging indefinitely into the void. The author’s focus, mirrored by the various adaptations which followed, was on chastising humanity for its treatment of Mother Earth and each other through symbolism, rather than creating a realistic depiction of the technical and sociological parameters of designing, operating, and living aboard a real generation ship on a mission to another star system. This is Angst Science Fiction at its best, after all.

As I have stated in my other essays involving science fiction, many people at all levels of education get their “knowledge” about many subjects from our entertainment media, especially if the topic is not of their specialty. Even when they know that the fiction they are watching is not a documentary, the public can be and often is left with an impression that what they have witnessed is fundamentally true: Unless they bother themselves to delve further into the matter to learn the real story and facts, this type of introduction remains in their minds and colors their perceptions.

Thus, I have created this section to focus on the technical aspects of Aniara despite its clear Angst SF pedigree. A critique of this film may also serve as a guide for the development of real generation ships, even when aspects might only show a potential designer what not to do in the process.

“All communication systems will be down until we’ve reached our destination.”

For reasons that apparently have to do with the advanced and rather mysterious (read technobabble) methods of space travel in this future realm that involve tensor fields and gravity, the Aniara and all other vessels like it are unable to either transmit or receive messages during its three-week voyage from Earth to Mars.

COMMENT: In the poem, the Aniara was able to send out a “hailing signal” as a distress call after the accident, but their cry for help “just echoed and re-echoed” the name of their vessel through “crystal clear infinity.”

Even if this nearly magical form of space travel cannot be circumvented when it comes to the ship’s communications, it only makes sense from a safety standpoint that the Aniara and all her sister transportation vessels should contain some form of emergency beacon that would automatically transmit a rescue signal in the event of an urgent problem – like plunging off course uncontrolled out of the Sol system, for example.

A THOUGHT: If the Aniara could not broadcast any electromagnetic messages, what about launching a physical one into the void? Might these goldonders carry distress beacons that could be ejected into space during an emergency, alerting all other vessels that something went wrong and how/where to find them.

If there is no technical way to send out even a simple distress signal, then what about the fact that the Aniara was scheduled to arrive at the space lift Valles Marineris over Mars in just three weeks’ time? I think it would be hard to miss an object that is sixteen thousand feet (4.8 kilometers or 3.03 miles) long and three thousand feet (914 meters) wide carrying eight thousand people, even in interplanetary space.

Nevertheless, we see no evidence that anyone came looking for the Aniara once it was determined that the vessel was missing. Perhaps they did, but the transport ship somehow eluded them. The probe that the crew detected in the fifth year of their journey might have been an attempt to rescue them (they speculated that it was large enough to carry nuclear fuel rods), but the fact that no one on the Aniara could figure out how to open it or learn what it carried tends to speak against that possibility.

YET ANOTHER THOUGHT: Emergency situations aside, would it not be dangerous for a busy interplanetary society with constant spaceship traffic to have certain, if not all, such vessels be lacking in the ability to communicate with anyone? Yes, space is both vast and multi-dimensional, but when you are confining spacecraft to certain routes, as would be the case in transporting refugees from Earth to Mars, then the narrowed flight paths might prove dangerous if not disastrous for those ships plying them while having no means to alert and warn off other ships, or be warned and alerted by others in turn?

“The power station caught fire and we had no choice but to eject all our fuel.”

In the film version of Aniara, the ship’s problems began when a random screw left in space penetrated its hull and hit the nuclear reactor. To avoid a deadly radioactive explosion, the crew ejected all the Aniara’s nuclear fuel rods into space. This left the vessel with no way to power its propulsion system or control their direction.

Looking into this situation, I found one commentor on this issue asking why the Aniara wasn’t designed to perform an emergency release of their nuclear fuel on very long cables far away from the spaceship? In this way, if the rods did not explode as the crew feared, they could easily retrieve them and return the power plant to working order.

I wondered why the Aniara’s nuclear fuel system setup was not located at a distance from the main ship to begin with? Plans for nuclear-powered space vessels going back to the pre-Space Age era had their nuclear engines placed at the far end of long boom systems to prevent any emitted radiation from contaminating the crew. The nuclear-powered Pioneer and Voyager deep space probes had their cylindrical RTGs, or Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators, attached on long metal booms to keep them as far as possible from the probes’ sensitive scientific instruments.

The Aniara seems to have had no contingency plans for such an emergency with its propulsion system, except to eject the nuclear fuel rods away from the ship and then have no means to recover them, assuming they did not explode in the process. Was there no backup engine for the vessel, even a non-nuclear one? Chemical rockets may have made their course back to Mars a slower one, but at least they would have arrived – and we know the Aniara had enough resources to last in space for years, if necessary. Certainly, such a large ship would have the room for a spare engine – either that or how about removing a few spas or restaurants to make space for the backup propulsion system?

What about escape pods or some kind of lifeboats? Nothing was said about such safety systems in the film, which are standard on modern day nautical cruise ships – and thanks to the tragic lesson from the sinking of the HMS Titanic in 1912, there are now enough emergency rescue vessels for every passenger to safely escape a ship in serious distress.

In Canto 78 of the Aniara poem, we are told how the Chief Engineer requested, upon his passing, to be buried in space aimed at the star Rigel inside a “rescue-module” – also referred to a “rescue-capsule” and “death-capsule” in the same canto as its purpose changed from a lifesaving device to a coffin.

Apparently, no one aboard the Aniara considered using one of these rescue-modules when their ship first went off course. Were there enough of them for eight thousand people? Would the onboard power-supplies and provisions last long enough for those using this escape pod to be recovered safely?

Of course, in the literary sense, none of this really matters because none of the Aniara’s passengers and crew are meant to escape the runaway vessel and thus their fate, which is death and only death.

By modern standards, a large passenger ship – be it on terrestrial waters or in the ocean of space – would have a means for travelers to get off their vessel in the event of a serious issue, such as its sinking or careening out of control into the blackness of the void. Even if there were not enough “rescue-modules” to accommodate every person, it is a certain bet that at least some of the passengers would attempt to use them to save themselves at the expense of others. That such a response never took place, or at least was never revealed to us, demonstrates both a serious lack of emergency planning on someone’s part and a level of restraint by otherwise desperate human beings that defies expectations.

COMMENT: I do get that having escape pods for a generation ship might be rather pointless and even cruel for such an expedition, except at its beginning and when the vessel reaches its presumably planetary destination. I might have added that perhaps these pods could be equipped with suspended animation systems, but that would go against the rule imposed here of needing a generation ship in the first place because the technology to successfully preserve a human body indefinitely has not manifested itself.

“Please note that checked containers will not be available during the voyage.”

What were these containers containing? Were passengers only allowed carry-on luggage holding just their clothes and immediate essentials such as medicines to store in their cabins? One possible exception was The Astronomer, who filled most of her shelves with astronomical texts. Why weren’t these containers available during the initial three-week voyage? Was it due to where and the way they were stored?

It is a more than a good bet that once it became clear the Aniara was never going to reach Mars, the passengers and crew alike would seek out every single container stored on the ship. As they were essentially on a refugee ship heading to drop off everyone but the crew at the Red Planet permanently, it is easy to assume that many of the items in the ship’s cargo hold were carrying vital supplies for the settlements there. These supplies would include food, plant seeds, and possibly various useful animals.

So why didn’t we see anyone attempting to grow gardens? There was a garden in the poem, even though it was both owned and controlled by Captain Chefone. If such edibles existed among the passengers’ belongings as well as official deliveries being sent to Mars, they should have had extra food beyond the initial two-month supply before having to rely on algae.

Were the filmmakers implying that this post-apocalypse humanity no longer knew how to grow vegetables and other flora for sustenance as a parallel to their neglect of Earth’s global ecosystem while embracing technology? That only the most artificial methods of processing life forms such as algae for food were the closest that humanity could come to farming in that future era.

The other frightening possibility is that there was a very limited supply of agricultural products left on Earth to bring along. The remaining plants and animals would be needed by those who could not afford to leave the home world for Mars or elsewhere in space.

These scenarios feel like a stretch in one sense due to the desire to survive that would be prevalent among the denizens of the Aniara. However, we must always keep in mind that symbolism takes precedence in this story. In the latter case, the passengers would not be allowed to set up farms and thus keep many of their fellow humans alive through a combination of emotional uplift and better sustenance.

With eight thousand people aboard the Aniara, there must have been at least some professionals and experts in a rather wide variety of fields who could have helped fix the ship in the early days of the crisis.

One logical assumption is that those who were allowed to move from Earth to Mars would possess certain skills and knowledge critical to the Martian settlements that would also translate to supporting the ship in its crisis. A space vessel as big and complex as the Aniara should already have had in place a good number of crew who were engineers, technicians, and mechanics.

Despite this logic, it is also possible that most of the people who made it onto the Aniara did so more through social connections and the ability to pay their way into space. After all, Earth’s climate was in a state of destructive change: The film opened with a montage displaying one natural disaster after another wrecking human habitats and infrastructure. We also witnessed early on from space the presence of a huge hurricane menacing the United Kingdom.

Perhaps all the above reasons are also why there seemed to be a lack of religious clergy and therapists among all the passengers despite the definite need for them with so many emotionally and physically scarred refugees. The Mima and her “handler” the Mimarobe were essentially pushed into these roles by the pressures of the anxious people around them until their respective breaking points.

Where were the AIs and the service robots on the Aniara, besides the Mima? There was some advanced technology on the ship, and of course the Aniara itself is an example of a sophisticated technological spacefaring culture. Nevertheless, many of the roles which could have been performed in this future humanity by machines were still being done by humans.

Once again, I must wonder if such artificial entities were in fact luxuries in a society that was attempting to escape their destroyed home world. I can see such machines with their complex and therefore expensive parts and materials being in short supply for a refugee ship. Humans, on the other hand, are probably still plentiful and willing to perform certain services in exchange for a way to escape their doomed planet.

As for a generation ship, one anticipates and hopes that AI and mobile service machines would be integral parts of the mission. That they could maintain and supervise generations of humans on the long journey would be critical for reaching their intended new home.

The famous nuclear fusion-powered Daedalus star probe, conceived by the British Interplanetary Society (BIS) in the 1970s, envisioned both a semi-intelligent (which I interpret as conscious and mentally aware) AI brain and multi-armed robots called Wardens that would maintain and repair the vessel during its fifty-year journey to Barnard’s Star (or a 36-year journey to the Alpha Centauri system had they decided to go there instead).

Perhaps a mix of humans and machines working together during the mission would be the best scenario for success. This way the humans would remain in the loop regarding key ship systems and operations and at the same time not become too dependent on AI and robots for their needs ala WALL-E.

Does Size Matter?

Perhaps the most prominent issue about the idea of sending humans on very long missions through deep space – such as a one-way journey to another star system involving the need for multiple generations of humans in order to survive the trip – is the ethical and moral concerns of having groups of people spend their entire lives in one place and exist ultimately to produce new people to ensure that there are enough humans when their vessel finally arrives at their new home.

This article by Neil Levyis, “a senior research fellow of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics and professor of philosophy at Macquarie University in Sydney”, looks at the pros and cons of such a plan:

https://aeon.co/ideas/would-it-be-immoral-to-send-out-a-generation-starship

This quote from the piece sums things up rather well, pointing out the parallels to living on the spaceship we call Earth:

Whether generation ships would be ethically permissible, despite locking children into a project and way of life that they didn’t choose, seems to depend on whether the goal – say, the survival of the species – is itself sufficiently valuable to justify it. That’s not a question I will attempt to answer. Given that generation ships remain a long way off, it’s not a pressing concern. But at different scales and in different forms, most children on Earth today were born into constrained futures, whether through poverty, religious beliefs or impending environmental degradation. Asking about the permissibility of generation ships might give us a fresh perspective on the permissibility of the constraints we impose now on human lives, here on the biggest generation ship of them all – our planet.

This second piece quote hits home even more succinctly:

The differences between Earth and generation ships are differences in scale, not in kind.

Looking further at Earth as a spaceship, this essay shows how the label is more than just a clever comment:

https://www.space.com/earth-iss-sustainable-living-world-space-week

To quote:

Imagine living in a place where your survival depends upon living within your limits, not consuming more food and energy than you produce, creating enough fresh water and air to live on, reducing waste to a bare minimum, recycling everything that you can, and avoiding contaminating the environment around you. This is what astronauts must face, to an extent, on board the International Space Station, and what they would have to face to a greater extent in future settlements on the moon or Mars.

But it’s also how we have to live on Earth if we are to protect our environment, which is one of the themes of this year’s World Space Week, running between Oct. 4 to Oct. 10. [2024].

A space station, or a lunar base, is largely a closed-loop system. What we mean by this is that it must produce its own resources and then recycle them, feeding them back into the system because they are limited. Consume too much, and astronauts might run out of air, food, water or energy, which could be fatal. Sure, there are occasional resupplies from Earth, however, so they are not 100% closed loop systems. What is a completely closed loop, however, is Earth itself.

This paper asks how large a generation ship would have to be to accommodate a mere five hundred human beings on an interstellar voyage:

In contrast, this article estimates around forty thousand humans would be required to properly settle an alien Earthlike planet:

http://www.space.com/26603-interstellar-starship-colony-population-size.html

“Do you want to just squeak by, with barely what you can get? Or do you want to go in good health?” Smith said on July 16 [2014] during a presentation with NASA’s Future In-Space Operations (FISO) working group. “I would suggest, go with something that gives you a good margin for the case of disaster.”

Revisiting the numbers

In the past, researchers have proposed that a few hundred people would be sufficient to establish a settlement on or near an alien planet. But Smith thought it was time to take another look.

“I wanted to revisit the issue,” he said. “It had been quite a long time, and of course we now know more about population genetics from genomics.”

For his study, which was published in April in the journal Acta Astronautica, Smith assumed an interstellar voyage lasting roughly 150 years. This time frame is consistent with that envisioned by researchers at Icarus Interstellar, a nonprofit organization dedicated to pursuing travel to another star.

Smith’s calculations, which combine information from population genetics theory and computer modeling, point toward a founding population of 14,000 to 44,000 people. A “safe and well-considered figure” is 40,000, about 23,000 of whom would be men and women of reproductive age, Smith writes in the study.

This figure may seem “astoundingly large,” Smith acknowledged, but he stressed that it makes sense.

“This number would maintain good health over five generations despite (a) increased inbreeding resulting from a relatively small human population, (b) depressed genetic diversity due to the founder effect, (c) demographic change through time and (d) expectation of at least one severe population catastrophe over the five-generation voyage,” Smith writes in the Acta Astronautica paper.

Data from the real world support the overall thrust of his findings, Smith added.

“Almost no natural populations of vertebrates dip below around five to 7,000 individuals,” he said during the FISO talk.” There are genetic reasons for this. And when they do go below this, sometimes they survive, but many times they go into what’s called a demographic or extinction vortex.”

Sending frozen sperm and eggs on the voyage with a limited number of human “tenders” is also an option, Smith said, though he didn’t consider it seriously in the new paper.

“It can be done, but it’s so different from the human experience of living in communities and so forth that I’ve kind of avoided that,” he said. “I’m kind of assuming, or sticking with, ‘What is the experience of humanity so far, and what can we learn from it?”

The Ship is the World

Another term for generation ship is World Ship, a logical term since these space vessels would be entire worlds in themselves. In 2019, Andreas M. Hein – who also authored that Centauri Dreams piece on comparing generation ships to cathedral building projects – and cohorts discussed the feasibility and rationale of World Ships at the ESA Advanced Concepts Team Interstellar Workshop. You can review their slide presentation for all the key technical details here:

https://indico.esa.int/event/309/attachments/3517/4683/World_Ships_-_Andreas_Hein.pdf

A detailed paper by the authors accompanies this presentation here:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.04100

Practical Politics and Real Economics

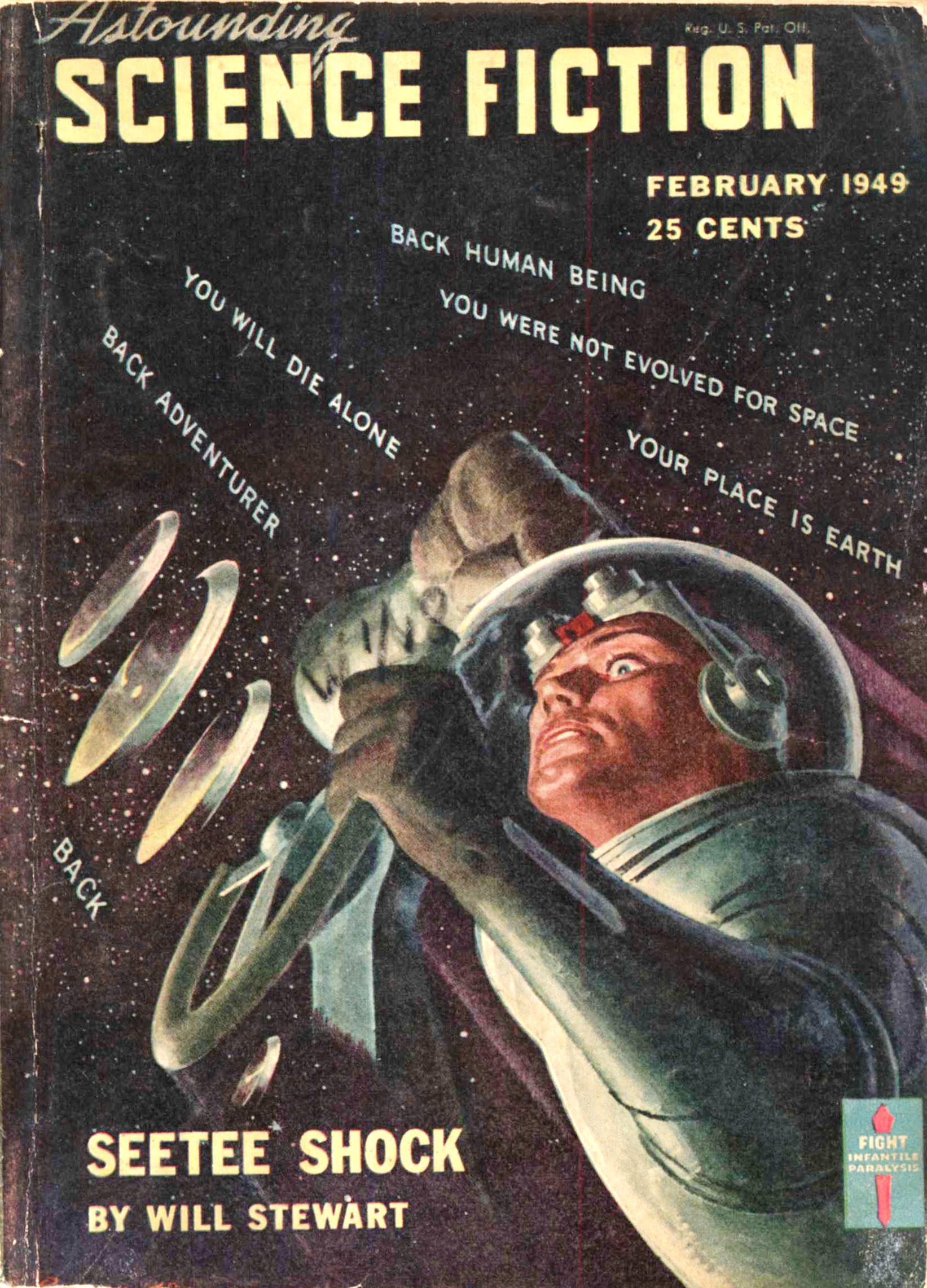

The February 1949 issue of Astounding Science Fiction magazine introduced a story by Will Stewart, one of the pen names for author Jack Williamson (1908-2006), titled “Seetee Shock” which may be read in full here:

https://s3.us-west-1.wasabisys.com/luminist/SF/AST/AST_1949_02.pdf

While the plot does not focus on either interstellar travel or generation ships, “Seetee Shock” does delve into the more practical aspects and obstacles of exploring and settling space – almost one decade before the official start of the Space Age. The story contains some very interesting and relevant commentary to supplement the themes of this essay. For example, read this quote, which literally speaks for itself:

“The trouble is what they teach you at school. They make everything seem too easy. They teach you astrogation and nucleonics and paragravitics and everything else in spatial engineering. You think you can make all the planets into scientific wonderlands. But you’re wrong, Nicky.”

Brand’s red, rawboned face, for an instant, seemed sadly wistful.

“Because they don’t teach you practical politics or real economics. The technical problems are easy, but they don’t teach you human nature. And that’s the real barrier to the sort of wonderland that young engineers dream about, Nicky. The blind ignorance and crushing stupidity and clutching greed and sheer cowardice of human beings!”

What initially brought my attention to this story was the cover of this Astounding issue: A suited astronaut piloting an unseen ship with a look of terror as he is surrounded by phrases exposing his fears of being immersed in the Final Frontier.

The publication cover mirrors the scenes in “Seetee Shock” where the character Jenkins has an inner monologue showing his fear of space and why. Certainly, these are thoughts that many if not most of the passengers and crew of the Aniara would readily empathize with.

The cover art for “Seetee Shock” from the February 1949 issue of Astounding Science Fiction magazine. Note the various universal expressions of fear humanity has about expanding into space.

Contemporary human minds can conceive of so many things that our current physical bodies cannot handle – nor our emotional states, or education levels for that matter. Nevertheless, our minds can also think of ways to help us expand into space – if not us in person, then perhaps our avatars or other representatives. Even relatively primitive deep space probes have handled functioning in space and on alien worlds for decades, better than any human could do without a lot of support.

So perhaps two of those phrases on the February 1949 Astounding cover illustration, “You were not evolved for space” and “Your place is Earth”, are more than just expressions of fear. If this is the case, and humanity cannot ply the galaxy with FTL craft, yet some will still want to move beyond our home planet, then what are the alternatives?

A Ten-Phase, 500-Year Program

Should it be determined that humanity cannot successfully complete a journey to another star system with representatives of our species at our current stage of evolution, Christopher E. Mason, a geneticist and computational biologist at Cornell University in New York, has offered a plan for modifying brave hominin adventurers in his 2022 book by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Press, The Next 500 Years: Engineering Life to Reach New Worlds.

On the publisher’s information page for this book, the introduction to the Description section gives a warning that shares more than a little with the main message in Aniara, as linked to from here:

An argument that we have a moral duty to explore other planets and solar systems—because human life on Earth has an expiration date.

Inevitably, life on Earth will come to an end, whether by climate disaster, cataclysmic war, or the death of the sun in a few billion years. To avoid extinction, we will have to find a new home planet, perhaps even a new solar system, to inhabit. In this provocative and fascinating book, Christopher Mason argues that we have a moral duty to do just that. As the only species aware that life on Earth has an expiration date, we have a responsibility to act as the shepherd of life-forms—not only for our species but for all species on which we depend and for those still to come (by accidental or designed evolution). Mason argues that the same capacity for ingenuity that has enabled us to build rockets and land on other planets can be applied to redesigning biology so that we can sustainably inhabit those planets. And he lays out a 500-year plan for undertaking the massively ambitious project of reengineering human genetics for life on other worlds.

As they are today, our frail human bodies could never survive travel to another habitable planet. Mason describes the toll that long-term space travel took on astronaut Scott Kelly, who returned from a year on the International Space Station with changes to his blood, bones, and genes. Mason proposes a ten-phase, 500-year program that would engineer the genome so that humans can tolerate the extreme environments of outer space—with the ultimate goal of achieving human settlement of new solar systems. He lays out a roadmap of which solar systems to visit first, and merges biotechnology, philosophy, and genetics to offer an unparalleled vision of the universe to come.

Mason also wrote an article adapted from his book examining the idea of a generation starship and how it may only work best with a genetically modified crew:

Quoting from the end of this piece:

But even with advanced entertainment and potential hope of a new, enhanced ship appearing any moment, would the crew still stare out the windows into constant star-filled skies thinking of blue oceans? Or would they perhaps be elated about being the “chosen ones” with an extraordinary opportunity to explore and, quite literally, build a new world? The reality is this ship would be their world, and, for most, it would be the only world they would get to experience.

Yet this limitation of experience is actually not that different from the lives of all humans in history. All humans have been stuck on just one world, looking to the stars and thinking, “What if?” This vessel, the Earth, while large and diverse, is still just a single ship with a limited landscape, environment, and resources, wherein everyone up to the 21st century lived and died without the choice to leave. A few hundred astronauts have left Earth, temporarily, but they all had to return. The generation ship is just a smaller version of the one on which we grew up, and, if done properly, it may even be able to lead to a planet that is better than what we inherited. The new planet could be fertile ground for expanding life in the universe, while also offering lessons on how to preserve life on Earth.

I also like this quote from rocket pioneer Robert H. Goddard (1882-1945) that introduces the article:

“The only barrier to human development is ignorance, and this is not insurmountable.”

Incidentally, this quote comes from a paper Goddard wrote on interstellar generation ships in 1918 titled “The Last Migration” where he then sealed it away in an envelope in a friend’s safe. Goddard’s manuscript was not published until 1972.

Goddard had dealt with public ridicule from the media for betting on rockets as a means of space travel and for reaching the Moon utilizing such a device. Undoubtedly Goddard assumed that suggesting a mission to the stars would be met with even more incredulity.

The father of American rocketry did provide a condensed version of his concept titled “The Ultimate Migration” which may be read here:

The ideas Goddard conceived for his generation vessels are ones familiar to us now, but the remarkable part is that he had thought of them at a time when few even considered the possibility, let alone go into any detail on the matter.

It is easy to see why The Next 500 Years author Mason would quote him and from where: Goddard mentioned how a crew might change physiologically as the generations passed aboard their atomic-powered starship. Should such a propulsion method be unavailable, Goddard suggested placing the emigrants into suspended animation.