Space writer Keith Cooper, the editor of the UK’s Astronomy Now, is currently attending the Royal Astronomical Society’s meeting in Llandudno, Wales — in fact, the photo of him just below was taken the other day in Llandudno. But the frantic round of presentations hasn’t slowed Keith down. When last spotted in these pages, he was engaged in a dialogue with me about SETI issues. That exchange got me thinking about having Keith talk to Michael Michaud, considering their common interests and realizing that they had already met at last year’s Royal Society meeting where so many of these issues were discussed. Michael was kind enough to agree, and what follows is an exchange of views that enriches the SETI debate.

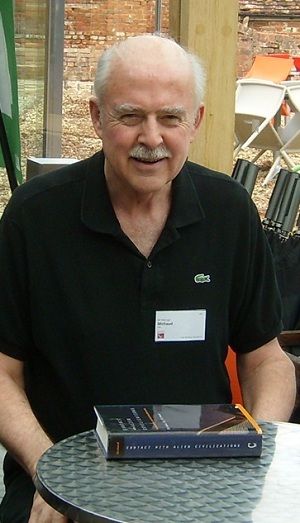

Centauri Dreams readers know Michael Michaud to be the author of the essential Contact with Alien Civilizations: Our Hopes and Fears about Encountering Extraterrestrials (Springer, 2006), but he’s also the author of over one hundred published works, many of them on space exploration and SETI. Michaud was a U.S. Foreign Service Officer for 32 years before turning full-time to research and writing. He had a wide variety of assignments during his diplomatic career, including Counselor for Science, Technology and Environment at the U.S. embassies in Paris and Tokyo, and Director of the State Department’s Office of Advanced Technology.

Michael was directly involved in the negotiation of international science and technology cooperation agreements, represented the Department of State in interagency space policy discussions, and testified before Congressional committees on space-related issues. It’s particularly germane to mention that he was actively involved in international discussions on contact issues within the International Academy of Astronautics for more than twenty years, and was the principal author of the so-called First SETI Protocol (actually entitled ‘Declaration of Principles Concerning Activities Following the Detection of Extraterrestrial Intelligence’). His recent work has focused on the importance of bringing more historians and other social scientists into debates about the possible consequences of contact.

- Keith Cooper

A few years ago I interviewed Andy Sawyer, the chief librarian and administrator of the Science Fiction Foundation at the University of Liverpool, and asked him about our predilection for alien invasion stories. “Because alien invasion stories are cool, and there are all sorts of anxieties that can be set in an invasion story,” he said. And I agree – I enjoy watching the latest alien invasion movie as much as the next person. But for many people their only exposure to ‘aliens’ is through the lazy stereotypes of Hollywood flicks, or perhaps the mono-cultural depictions in Star Trek, and this is driving how they envision real alien civilisations to be. Michael, in your work raising awareness of the consequences of METI you’ve helped bring home the fact that our ideas about aliens are just too simplistic, and consequently our visions of contact are equally superficial.

At the Royal Society last October you spoke of binary stereotypes – the wise old aliens happy to pass on their knowledge to us and teach us to become better beings, and the nasty, snarling conquerors hell-bent on wiping us off the face of the planet and stealing all our women and water (as the B-movie SF tropes usually go). What seems a shame is that some scientists in the SETI community have slipped into taking the first of these stereotypes for granted; the notion of an Encyclopedia Galactica is wholly expected by many, but this requires an enormous act of altruism on behalf of the sender.

I’ve seen lots of arguments suggesting that advanced extraterrestrials will inevitably be altruistic, yet it seems to me to be mainly the astronomers, speaking outside of their field of expertise, who are advocating such optimistic assumptions (without even defining what they mean by altruism – kin, or nepotistic altruism, is very different from reciprocal altruism, which is probably what they are referring to). Whenever I speak to evolutionary biologists, anthropologists, philosophers and other social scientists – people whose job it is to study social behaviour – they are much more cautious. For instance Professor Jerome Barkow, a sociocultural anthropologist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, described to me one possible example of “a fear-filled species, hypersensitive to danger, who have evolved intelligence selected for fear because it was the only way they could manage to win in competition against related species.”

Such a fearful species may constantly be on the lookout for danger, and in the worst case scenario may even be xenophobic. Simon Conway Morris, a paleontologist at the University of Cambridge who champions the idea of convergent evolution, is even more blunt: “If intelligent aliens call, don’t pick up the phone!” Meanwhile, Professor Nick Bostrom, Director of the Future of Humanity Institute at the University of Oxford, told me that “even if we could detect a pattern of increasing moral enlightenment in human history, it would be hazardous to extrapolate from that into our future, but I imagine that is what would underpin some people’s optimism about technologically advanced civilisations. As for altruism, we just have no idea about that.”

There are so many questions I would like to ask. My main question to you Michael is why are we not listening to those with the knowledge base of human behaviour who are best-placed to make judgments about the possible actions of extraterrestrials? Does SETI run the risk of becoming too exclusive? How can we expand the discussion to include people from all disciplines all around the globe? Furthermore, at the Royal Society, you said that it was time to make the most objective analysis that we can of the benefits and risks of METI. How do we escape the cliche of invasion to investigate the subtler pros and cons of contact?

- Michael Michaud

Keith, I agree with much of what you say. Escaping the stereotypes that bedevil discussions about contact with ETI will not be easy. Because we have no confirmed information about the nature or behavior of extraterrestrial intelligence, our speculations about contact rest on belief, preference, or analogies with ourselves. Many people are impatient with the resulting ambiguity and want binary, either-or answers.

Early SETI advocates promoted the image of aliens as altruistic philosopher-kings not only because of personal preference, but also because they were trying to gain public support for a highly speculative endeavor. An idealistic and hopeful vision was a better sales pitch. For SETI advocates, that became the default position in discussions about the consequences of contact. Media treatments of contact issues, including documentaries, also are driven by what producers think will sell. Alien invasions — or wise, harmless extraterrestrials — overpower sober analyses based on what we know of human behavior. My responses to questions from three companies producing TV shows on the alien invasion theme were politely rejected not because they were wrong, but because they were less exciting than a war game.

Historians and other social scientists could offer more grounded visions of contact based on their studies of the only technological intelligent species we know – ourselves. For example, the human experience suggests that civilizations are not by nature either hostile or peaceful; their actions depend on the circumstances of the moment. Unfortunately, there is very little research funding or career reward for doing such work.

Many physical and biological scientists are not listening because they are skeptical of social science findings. Papers on social science issues such as the consequences of contact were pushed into the last hour of the last day of the June 2010 Astrobiology Conference. Yet some physical and biological scientists make sweeping statements about the behavior of intelligent beings that are not empirically grounded in the human experience. Imagine the reaction if a group of social scientists published conclusions about physical or biological processes without confirmed evidence.

How can we expand the dialogue about the consequences of contact? One starting point might be for a worthy organization interested in policy or social science issues to invite physical, biological, and social scientists to a themed conference on the benefits and risks of contact, including examples from human history. The Royal Society has set a useful precedent. I have some additional thoughts on this issue, but will hold them until I have your response.

- Keith Cooper

Michael, I’m intrigued by your comment that a hopeful and optimistic vision of contact has been adopted because it makes a better sales pitch. It strongly echoes something that James Benford commented on following my previous SETI dialogue with Paul, namely the claim that Arecibo could detect a signal from another Arecibo 500 light years away is a myth perpetuated as part of SETI’s sales pitch.

[PG comment: Excuse me for interjecting, but I want to add that Benford has added material on the Arecibo signal in a revised edition of his paper “Costs and Difficulties of Large-Scale ‘Messaging’, and the Need for International Debate on Potential Risks,” written with John Billingham. This latest version is not the one currently up on the arXiv server, so let me quote from what Benford says:

A similar argument quantifies the ‘Arecibo Myth’, i.e., that that Arecibo (Earth’s largest radio telescope) would be able to detect its hypothetical twin across the Galaxy (Shuch, 1996). Arecibo can’t realistically communicate with another Arecibo over such distances. Those who so claim do not state their assumption that the bandwidth will be extremely narrow (0.01 Hz), that both the receiver and the transmitter will stare exactly at the right very small part of the sky, tracking each other and that the receiver will track for hours in order to integrate a very weak signal and that no information will be sent. This last point is that, because the bandwidth is so small, the bit rate is glacial, far less than the slowest modem, maybe a bit per hour in the best case.

Sorry for the interruption, and now back to Keith].

Of course we want the public, and those who would finance SETI, to feel hopeful about the possibility of contact. The detection of a message from another intelligent civilisation would be profound in ways that we are only beginning to perceive, both scientifically and culturally, and we can only explore those consequences with the aid of social science. Despite having an astronomical background, I do find the social science aspects of contact equally as fascinating as the physical science of the search itself. I’ve learnt so much more about the human experience through my reading as I try to understand the nature of contact than I otherwise would have. SETI is a rare merging of the physical and social sciences and is all the richer for it – those that push cultural and sociological debates on contact to the end of conferences, to footnotes in papers and wave them away in vague, sweeping gestures on alien altruism do SETI a great disservice.

The social sciences do not necessarily come down against METI and the hope for peaceful and rewarding contact – there are compelling arguments both for and against (as an example of the former, I’d cite Professor Steven Pinker of Harvard University championing the ‘myth of violence’ and the notion that we are becoming more peaceful as we become culturally and technologically more advanced – see his TED talk on the subject – the idea is that we could use this as a template for alien civilisations). What the social sciences do show is that the consequences of contact are more complex than the threat of invasion or dreams of uplift by wise philosopher kings.

This dialogue is about alien motivations; fear seems to be a standout candidate, as Jerome Barkow alluded to. Adrian Kent at the Perimeter Institute has taken this to extremes to explain the Fermi Paradox in his recent paper ‘Too Damned Quiet.’ Here he argues the Galaxy is quiet because natural selection chooses civilisations that remain inconspicuous in the face of galactic predators. He writes:

“Advertising our existence in such an environment would be risky: a predator species might decide it could afford to predate on us, and even a reticent neighbour species might decide it could not afford to leave us attracting the attention of predators to the neighbourhood.”

While Kent’s fear-filled, predator-dominated Galaxy is at the extreme end of possible contact scenarios, it is something to be aware of. So too are the more subtle aspects that are often dismissed in the face of sensational stories of alien invasion. But we have to be able to discuss all the possibilities without fear of prejudice. No one can say what alien motivations will be, and I’m not trying to argue for any particular viewpoint other than all possibilities are currently fair game.

SETI’s current sales pitch seems to be holding back the wider debate. We have both commented on the often abysmal reporting of the consequences of contact in the media. I’d like to begin to change this, here and now. We need a new sales pitch. Through SETI we’re trying to find our place in a Universe that could be equally full of exquisite wonders and terrifying dangers, and everything in between. If we cannot guarantee a vision of contact that is as idealistic as the one that went before, then Michael what should our new message be?

- Michael Michaud

So, where do we go from here? First, it is time to free ourselves of the binary stereotypes that Hollywood, the Cold War, and the political reaction to it have imposed on us. We should be wary of both utopian and apocalyptic predictions of what contact might bring. We have no basis for assuming that other technological civilizations would welcome contact with us, nor do we have any basis for assuming that they would be hostile.

Second, it is time to fill in the middle ground between the extremes of a helpful altruistic message and an alien invasion. There are lots of other potential scenarios of contact, many of which have appeared in science fiction. For example, what if we detect a one-time alien signal not meant for us and are unable to find it again? What if that signal is nothing more than a dial tone? That would be contact without either communication or danger.

What if we find evidence of astroengineering on a scale far beyond our own abilities? That would imply a civilization so technologically powerful that it might consider us irrelevant, if it even noticed our existence. (In Arthur Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama, a giant alien space craft using our sun for a gravitational assist passes through our solar system without stopping, or communicating.) What if we find an alien probe in our solar system that is doing nothing we can detect – no messages, no firing of weapons, not even a friendly glow? Such a probe might have been another civilization’s response to detecting signs of biochemistry in earth’s spectrum a billion years ago. (Would they be looking for the same kinds of evidence we seek? If not, they might miss Earth life.)

There are hopeful signs. Recent frictions among those interested in this issue may reflect a broadening and maturing of the debate. While some astronomers still dismiss the possibility of interstellar flight even by uninhabited machines, Seth Shostak of the SETI Institute has recognized in print that we humans could launch robotic interstellar probes by the end of this century. That puts the possibility of direct contact back on the agenda. No Star Trek aliens would walk down the ramp; we would be dealing with smart machines.

Third, those of us active in this field should evaluate the implications of alternate scenarios of contact as best we can. One starting point might be the Rio Scale proposed eleven years ago by Ivan Almar and Jill Tarter.

Fourth, we need to get more high-profile figures from the social sciences to speak or publish on this question. To me, the most relevant discipline is the history of contacts between human civilizations. I would love to hear what iconoclastic historians like Niall Ferguson and Felipe Fernandez-Armesto would say about the consequences of contact with extraterrestrials in a diverse set of scenarios. Prominent historian William McNeill warned many years ago that the human precedent is not encouraging.

Fifth, we need to bring into this debate younger people who are free of the ideological blinders of both the Cold War and the political and ideological reactions to it. That may mean people less than forty years of age. There are signs of hope. Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David Hackett Fischer put it this way: “After the delusions of political correctness, ideological rage, multiculturalism, postmodernism, historical relativism, and the more extreme forms of academic cynicism, historians today are returning to the foundations of their discipline with a new faith in the possibilities of historical knowledge.”

You ask what our message should be. That has to evolve from discussions among many thoughtful people. I can only offer a suggested formulation: Open eyes, patience and prudence. Accept what our searches tell us about the universe and about the behavior of intelligent beings, whether we like those findings or not. Recognize how new we are on the interstellar scene, and how much we have to learn. In trying to foresee the consequences of contact, keep in mind the only data base we have: our own history. I hope that you will use your journalistic skills to keep this discussion lively, and tolerant.

Rob Henry said on April 26, 2011 at 16:42:

“I find that the second half of that sentence starts “if they were going to [destroy humanity] it would be done powerfully and quickly”. Surely this would only indicated from our own historic evidence, if they saw us as near equals. In any other circumstances it would be leisurely and slow, such as the mysterious and well documented worldwide drop in sperm counts that is actually occurring right now.”

My response:

Unless the galaxy is like the one depicted in Star Trek and/or some ETI really do want our physical selves for some reason, I do not assume that other beings in the Milky Way would be at our current level, let alone look or act like us in most respects. The odds seem against it when you take all the factors into account, especially if you assume they all evolved on their own worlds naturally without any deliberate intervention from others.

Therefore, such ETI should either ignore us due to our major differences (if they are even conducting any kind of SETI program at all) plus the incredible distances involved, or if they want our Sol system including Earth should get right down to business and remove any obstacles with speed and efficiency. Subtle manipulations or a drawn-out military style invasion would be a high expenditure of time and resources. Even the recent SF film Battle: Los Angeles, for all its many flaws, at least had the aliens, who were invading Earth for its natural resources, waste no time in trying to remove humanity on their way to their real goal.

For more of my thoughts on how and why an ETI might attack us, you can read my two-part article on this subject starting here:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=14703

Regarding your comments about the recent demise of The SETI Institute’s program with the ATA, I agree with you that the search needs to expand beyond just the radio realm of distant solar systems. The problem is that the ATA project was finally going to be the big, dedicated SETI I and others have been hoping would happen for decades, rather than taking scraps from the table of the other astronomy facilities. We have been pushed back to Square One.

In addition, the public still tends to perceive SETI as this big, monolith entity that has groups of dedicated radio astronomers listening to the stars 24/7 with headphones, all funded by The Government. The SETI Institute is often perceived as that entity, due to no small part by them.

Hopefully this event will stir certain groups to save the effort as happened when politicians cut down NASA’s SETI program in 1993. Maybe this time SETI can be expanded among more diverse groups to seriously look for astroengineering projects and probes in our Sol system as well as radio and optical signals and others.

What I disagree with is that the knowledge that we wish to communicate with them could have no conceivable effect on them. Also, I feel that the more powerful and deeper reaching METI that we would be capable of sending a few decades hence, might reach much further than Earth’s biological signs.

It’s the transmitting blindly and in complete ignorance I have a problem with. Even if someone is on the receiving end of one our signals, we have no idea how to make it the least bit meaningful. In a few decades we’ll be able to directly search for signs of life on other worlds; if nothing else, wouldn’t it be far more effective and efficient to wait until then?

Would we not want our first official attempt at contact to be as effective as possible?

Zaitsev – Your letter does not address beam propagation at all. Radar for NEOs is strong precisely because their signal strength drops rapidly over distance!

I presume METI transmissions are extremely narrowband.

It is very important to understand: both NEO Radar Research and Messaging to ETI are using the same powerful instruments: Arecibo Radar Telescope (ART), Goldstone Solar System Radar (GSSR), and Evpatoria Planetary Radar (EPR).

Also, it is very important to understand: “addressless” RADAR transmissions and targeted METI are absolutely equivalent, because monster super-aggressive and super-powerful ETIs may live anywhere. And detection range depends on the radiated energy, and is independent of signal bandwidth.

“…detection range depends on the radiated energy, and is independent of signal bandwidth.”

What??? This is simply wrong.

SETI: The transmission rate of radio communication and the signal’s detection

Authors: P. A. Fridman

(Submitted on 15 Feb 2011)

Abstract: The transmission rate of communication between radio telescopes on Earth and extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI) has been calculated up to the distances 1000 light years. Phase-shift-keying (PSK) and frequency-shift keying (FSK) modulation schemes are both considered here.

It has been demonstrated that M-ary FSK is advantageous in terms of energy. Narrow-band pulses scattered over the spectrum can be the probable signals of ETI and modern SETI spectrum analyzers are well suited to searching for these types of signals.

Such signals can be detected using the Hough transform which is a dedicated tool for detecting patterns on an image.

The time-frequency plane representing the power output of the spectrum analyzer during the search for ETI gives an image from which the Hough transform (HT) can detect signal patterns with frequency drift.

Comments: 20 pages, 8 figures, submitted to Acta Astronautica

Subjects: Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics (astro-ph.IM)

Cite as: arXiv:1102.3332v1 [astro-ph.IM]

Submission history

From: Peter Fridman [view email]

[v1] Tue, 15 Feb 2011 16:36:51 GMT (861kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/1102.3332