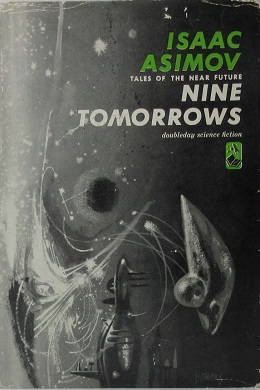

Science fiction collectors may well look a the two images below and think they’re both Richard Powers’ artwork, so prominent on the covers of science fiction titles in the mid-20th Century. Powers worked often for Ballantine in the 1950s and later, always refining the style he first exhibited when doing covers for Doubleday in the 1940s. The top image here is from one of the Doubleday titles, but I think of Powers most for his Ballantine work. His paintings could make a paperback rack into a moody, mysterious experience, a display of artistry that moved from the surreal to the purely abstract. At his best, Powers’ renderings seemed to draw out the wonder of the mind-bending fiction they encased.

What we have in the second image, though, is not abstract art but the manifestation of what is being described as “the world’s largest turbulence simulation.” The work comes from a project described in a new paper in Nature Astronomy, where lead author James Beattie describes his investigations at the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics, where he is probing magnetism and turbulence as they occur in the interstellar medium. In this image, Beattie’s caption describes “…the fractal structure of the density, shown in yellow, black and red, and magnetic field, shown in white.”

And while Beattie may or may not be familiar with Richard Powers, he does have an eye for the art that this kind of turbulence can produce, saying:

“I love doing turbulence research because of its universality. It looks the same whether you’re looking at the plasma between galaxies, within galaxies, within the solar system, in a cup of coffee or in Van Gogh’s The Starry Night. There’s something very romantic about how it appears at all these different levels…”

And honestly, doesn’t this remind you of Powers?

What Beattie and team have produced, using the computing muscle of the SuperMUC-NG supercomputer at the Leibniz Supercomputing Centre in Germany, is helping us better understand the nature of the interstellar medium. In particular, it is a computer simulation that explores the interactions of magnetism and turbulence in the ISM, which addresses magnetism at the galactic level as well as individual astrophysical phenomena such as star formation. Beattie’s team is international in scope, with co-authors at Princeton University, Australian National University, Universität Heidelberg; the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian; Harvard University; and the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

So what is the turbulence Beattie is describing? The phenomenon is ubiquitous, showing up in everything from cream swirling in a black cup of coffee to ocean currents to particles moving in chaotic flows in the solar wind. We can produce ultra-high vacuums on Earth, but even in these there are far more particles than are found in the average sample of the ISM. Despite the fact that so few particles exist in the ISM, though, their motions do generate a magnetic field, one that the researchers liken to the motion of our Earth’s molten core which generates the magnetic field that protects us.

The galactic magnetic field is weak indeed, but it can be modeled for the first time at a level of accuracy that is both scalable and high in resolution. At its highest setting, Beattie’s simulation can depict a volume of space 30 light years to a side, but can be scaled down by a factor of 5000 to explore smaller spaces. The latter has implications for how we study the solar wind, which not only produces ‘space weather’ but is also a factor in certain space sail concepts that use superconducting rings to produce a strong magnetic field that can harness the solar wind as thrust.

Always keep in mind that we have anything but a uniform interstellar medium. Some of the early writing about Robert Bussard’s ramjet concepts noted that a design that harnessed interstellar hydrogen would thrive best in dense star-forming regions, where hydrogen would be plentiful. The Bussard concept has fallen on hard times given issues with drag that seem to knock it out of contention, but magsail work remains interesting both as a way of harnessing solar wind particles or braking against the same upon entering a destination stellar system. So the more we can learn about the extreme density variations in the ISM, the better we can envision future interstellar flight.

Moreover, star formation is implicated in the same model. The better our simulations of interstellar turbulence, the more we can learn about the magnetic forces that push outward against the collapse of a nebula that will eventually produce one or more stars. And the model the team has developed stacks up well when run against actual data from the solar wind, which points to short term gains in the forecasting of space weather, the ‘rain’ of charged particles that affects both Earth and spacecraft.

The ubiquity of chaotic turbulence and its coupling with the galaxy’s ambient magnetic fields makes its study all the more provocative. Both generating and scattering off the plasma phenomena known as Alfvén waves, cosmic rays are strongly affected. From the paper:

In the cold (T ≈ 10 K) molecular phase of the ISM, [turbulence] changes the ionization state of the plasma by controlling the diffusion of cosmic rays [1–5], gives rise to the filamentary structures that shape and structure the initial conditions for star formation [6, 7], and through turbulent and magnetic support, changes the rate at which the cold plasma converts mass density into stars [8–13].

So there is plenty to work with here. And a brief return to van Gogh’s ‘The Starry Night,’ which Beattie mentioned in the quote above. Come to find that the author and co-author Neco Kriel (Queensland University of Technology) have produced a paper on the subject called “Is The Starry Night Turbulent?” The goal was to learn whether the night sky in this famous painting “has a power spectrum that resembles a supersonic turbulent flow.” And indeed, “‘The Starry Night’ does exhibit some similarities to turbulence, which happens to be responsible for the real, observable, starry night sky.”

Which I think only means that van Gogh was turning what he saw into art, recognizable to us precisely because it did reflect the night sky he was observing. Still, it’s fun to see these methods, which draw on deep research into turbulent interactions, applied to a cultural icon. I wonder what Beattie’s team would dig out of a deep dive into Powers’ work in the century after van Gogh?

Image: van Gogh’s ‘The Starry Night’ is Figure 1 in Beattie’s paper with Kriel. Caption: Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night, accessed from WallpapersWide.com (2018). We see eddies painted through the starry night sky that resemble the structures comparable to what we see in turbulent flows.”

The paper is Beattie et al., “The spectrum of magnetized turbulence in the interstellar medium,” Nature Astronomy 13 May 2025 (abstract / preprint). The paper on van Gogh is Beattie & Kriel, “Is The Starry Night Turbulent?” available as a preprint.

Turbulence is so apparent everywhere. I recall watching the smoke from my father’s cigarettes rising in a smooth, laminar flow, and then breaking up into turbulent coils.

A relatively recent image of Jupiter’s pole showing cloud turbulence and cyclonic vortices:

cyclones swirling above Jupiter’s poles

Turbulence in Jupiter’s clouds: Turbulent clouds in Jupiter

But just what are those turbulent objects in Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”? Something he imagined between the stars? Clouds? Imagined winds? His emotional turmoil at the asylum at the Saint Paul de Mausole asylum, where he painted?

Starry Night

I have that same copy of Asimov’s “Nine Tomorrows”. I cannot help thinking that the cover design deliberately reduced the Powers’ artwork to monochrome to save printing costs. It is a very drab cover. Several of Asimov’s novels and story collections had already been published with the vibrant colors typical of Powers’ palette, especially reds. Powers was a very prolific cover artist as this list of his sci-fi illustrations proves: Richard Powers art at isfdb.org

I agree with you about the lack of color. But I wanted to use that particular image because of the fit it made with the later simulation image. Powers’ colors were always brilliant, as you say.

>what are those turbulent objects in Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”?

Van Gogh painted the starry night in Arles in the south of France. In this region, there is a very specific wind called the ‘Mistral’ * a dry wind that blows strongly. If I remember my art history lessons correctly, this is what he wanted to reproduce on his canvas. Don’t forget that he was hypersensitive. He painted what he saw, especially the light. (Note the way he painted the crescent moon and its halo). In his letters to Theo or his biographies, it is never mentioned that he had an interest in astronomy.

*https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mistral_(wind)

@Fred

The Wikipedia article states that there is are different interpretations about the sky as Van Gogh never explained this. Even a website for MoMA is coy about the interpretation. While it could be a wind, one cannot paint a wind beyond a limited perception. If there are leaves blowing around you might see a portion of the wind turbulence. Unless there are other objects in the sky, e.g. clouds, any perception of a wind is only the point sensor of your body. This cannot provide any larger observation of the wind. IOW, if he was painting the Mistral wind, then it is his imagination, not objective reality.

All of this is simply to say that a simulation of turbulence, or an image of turbulence, are representations of the spatial features of the phenomenon, unless one can create some sort of spatial sensor (e.g. smoke, dyes, etc.) to create an image, then an invisible turbulence cannot be visualized, and reproduced even impressionistically, on a surface. Unless one can realistically reproduce the nature of turbulence, it should not match analytic methods to describe turbulence. [The nature of Jackson Pollock’s art approach of throwing paint did somewhat reproduce fractals that could be determined by analysis.]

another good explanation about “the starry night” :

https://www.arsmundi.de/en/service/our-art-report/famous-works-analysis-of-starry-night-by-van-gogh/

I agree with that. Jung would interpret that painting as an over active imagination which is a doorway or window into the collective unconscious with it’s archetypes and universal symbols like the Sun or Hero, and night, the shadow and darkness, the four elements which each have a different color, so outer space can be a carrier of those projections. Pablo Picasso was even more surreal and abstract with bright colors which get the attention of the conscious. Jung 1934/1950, 1953

Richard Powers (1921-1996) is one of my favorite SF cover artists. Some of his work:

https://www.richardmpowers.com/

Beattie’s work would not be out of place in a collection of Power’s artwork!

Hi Paul

> doesn’t this remind you of Powers?

no…. J. Pollock :)

Not far off the gallatic magnetic field image.

https://cdn.sci.esa.int/documents/34222/35279/1567215602042-Planck_The_magnetic_field_along_the_Galactic_plane_625.jpg

Emergence of order in turbulent and chaotic systems

Hi Paul…and thank you for this surprising and delightful edition!

I suppose that ‘surprising’ is far from the best word; you’ve posted cover images and discussed the artists many times, bringing light on a quite unappreciated genre.

Thanks.

Always a pleasure, as it always is to see you in the comments section. Many thanks for your contributions over these many years.

these turbulences seem typical of plasmas, and the matter that makes up ours is one of them. We now know how to build vehicles that can travel in these plasmas at very high speeds, but which require a lot of energy. The question is: will we be able to build spaceships – and thus harness enough energy – to travel between worlds, carried by these plasmas ?

I tried posting this a few days back, but apparently the site is blacklisted and the post disappeared without trace, so I’ve taken out the link html and the https: below:

I felt curious whether the turbulence itself contains enough energy to hypothetically extract energy from for some clever spaceyacht-tacking scheme. So, I asked the AI in https://www.perplexity.ai/search/based-on-https-arxiv-org-pdf-2-gfomKEcoR32wZ0iggJqKRQ (this answer thread). It came up with a convincing calculation for an underwhelming 80, nay *3.3* microjoules per cubic kilometer, as opposed to 1 kJ for fusing the hydrogen, or 110 kJ for total conversion. It also answered that a galactic bone might have medium ten thousand times more concentrated, but the extractable energy from turbulence probably would increase by a much lower proportion.

Answer threads of the type I cited can be added to by anyone with the URL (any reader here) – alas only for a fortnight. Now mind, in this case the AI did something wrong at first, but it was a common human mistake, made in a human way. There is no way on Earth I believe it averaged up sentences to find the next probable word to generate this result! I think it would be interesting if people here made a practice of using these for ongoing discussions – it should be an entirely new type of conversation, and I think it has great potential for as long as it is permitted to go on. Bring your critical thinking. :)

Very interesting that Perplexity allows this almost email-like thread to be shared so that a conversation including Perplexity’s LLM to supply answers (and calculations) can be managed. This is the first time I have seen this. It could be very useful to open up interactions with AIs to larger groups rather than individuals, potentially improving the conversation, or at least increasing its speed of coming to a conclusion.

Do you know if this is a unique feature or whether other LLM platforms allow the same approach?

Well, apparently the https: was NOT the cause, so it’s not much of a blacklist. If you see this post I was wrong about the link code also. (this is just the same link as a test) Sorry for making blind statements about computer mishaps; I ought to know better!