Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

ETI in our Datasets?

A recent workshop at Ohio State raises a number of interesting questions regarding what is being referred to as ‘high energy SETI.’ The notion is that places where vast energies are concentrated might well attract an advanced civilization to power up projects on a Kardashev Type II or III scale. We wouldn’t necessarily know what kind of projects such a culture would build, but we might find evidence that these beings were at work, perhaps through current observations or, interestingly enough, through scans of existing datasets.

Running June 23-24, the event was titled “Bridging Multi-Messenger Astronomy and SETI: The Deep Ends of the Haystack Workshop.” ‘Multi-messenger astronomy’ refers to observations that take in a wide range of inputs, from electromagnetic wavelengths to gravitational waves, from X-rays through gamma ray emissions. Extend this to SETI and you’re looking in all these areas, the broad message being that a SETI signature might show up in regions we have only recently begun to look at and may have prematurely dismissed.

Notice that such ‘signals’ don’t have to imply intended communication. We might well turn up evidence of advanced engineering through astronomical plates taken a century ago and only now recognized as anomalous. This kind of search is deliberately open-ended, acknowledging as it does that civilizations perhaps millions of years ahead of us in their history might be far more occupied in their own projects than in trying to talk to species in their infancy.

As I mentioned in SETI at the Extremes, Brian Lacki (Oxford University) and Stephen KiKerby (Michigan State) have produced a white paper on the workshop, an overview that puts the major issues in play. The high-energy bands that we have been talking about recently have seldom been explored with SETI in mind, given the natural predisposition to think that life would be something rather like ourselves, and certainly not capable of existing on, say, a neutron star. High-energy SETI pushes the idea of astrobiology into these realms anyway, but equally significant, makes the point that whatever their makeup, advanced aliens might exploit high-energy sources whether or not they had evolved on them. Thus these energy resources become SETI targets, in the hope that activity affecting them will throw a signature.

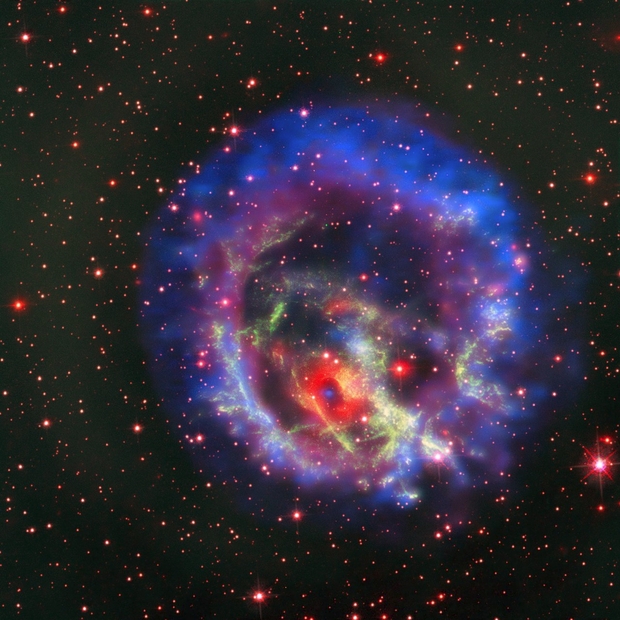

Image: The area around Sgr A* contains several X-ray filaments. Some of these likely represent huge magnetic structures interacting with streams of very energetic electrons produced by rapidly spinning neutron stars or perhaps by a gigantic analog of a solar flare. Scattered throughout the region are thousands of point-like X-ray sources. These are produced by normal stars feeding material onto the compact, dense remains of stars that have reached the end of their evolutionary trail – white dwarfs, neutron stars and black holes. Because X-rays penetrate the gas and dust that blocks optical light coming from the center of the galaxy, Chandra is a powerful tool for studying the Galactic Center. This image combines low energy X-rays (colored red), intermediate energy X-rays (green) and high energy X-rays (blue). Credit: NASA/CXC/UMass/D. Wang et al.

Let’s acknowledge our ignorance by recognizing that the motivations of any off-Earth civilization are unknown to us, and for all our logic, we have no notion of what such a culture wants to do. It’s a helpful fact that technosignature searches don’t require futuristic off-planet observatories. Reams of observations have been recorded that have seldom if ever been actively mined. Thus high-energy SETI, exotic as it is, can proceed with existing materials, even as ongoing astrophysical research continues to produce new data that add to the mix.

As the authors note, high-energy radiation has many sources, from nuclear processes, from gamma ray emissions and neutrinos to relativistic particles, which include not only cosmic rays but particles thrown out by jets and the interaction of electrons and positrons. We can study compact sources like neutron stars and black holes (ideal for energy extraction) and relativistic flows from energetic transients. Gravitational waves might be used to bind together elements of a galactic network. How exactly might ETI modify any of these?

It’s natural to ask whether X-ray astronomy has implications for SETI. Bursts of emission using X-rays for communication, exploiting less diffraction and the ability to produce tighter beams, might be detected if aimed specifically at us, making something like a flash at these frequencies from a nearby star an anomalous event worth studying. Or consider signals more general in nature:

Non-directional X-ray communication can be effected by dropping an asteroid onto a neutron star [4]. When it hits, it releases a burst of energy detectable at interstellar distances. The cosmos also has a number of compact high-energy “signal lamps”. X-ray binaries (XRBs) are systems with a neutron star or black hole accreting from a donor star, having luminosities of up to 105 suns. Even a kilometer-scale object passing in front of the hotspots of an XRB can easily modulate its luminosity, serving as a technosignature [4, 16]. A subplanetary-scale lens is potentially capable of creating a brief flash visible even in nearby galaxies without any power input of its own. Credit: NASA/CXC/UMass/D. Wang et al.

We don’t have a handle on how to use neutrinos for communication, although there have been experiments along these lines given the ability of neutrinos to pass right through obstacles and thus probe, for example, the oceans of icy moons. But perhaps we can home in on industrial activities, which as the authors point out, could involve not just energy collection to power scientific experiments but interstellar propulsion through antimatter rockets. The interactions between a relativistic spacecraft and the interstellar medium could become apparent through gamma rays, while X-ray binaries might show oddities in their proper motion indicative of their use as stellar engines.

This possibility, studied at some length by Clément Vidal under his ‘stellivore’ concept, stands as a particularly detectable phenomenon:

What are the limits of life, broadly defined? At the very least, complex processes require a thermodynamic gradient to feed them. In his reflections on the future of the cosmos, Dyson suggested that this is the only absolute requirement, and that long after the stars have gone out, life could still thrive in the chilly atmospheres of cooled compact objects [7]. A contemporary test of this admittedly extreme idea might be found with today’s compact objects. The accretion hotspots of XRBs have some of the greatest sustained power densities around in the contemporary universe. If thermodynamics really is the only prerequisite factor for complexity and ETIs can withstand the incredibly hostile environments, they may find the energy gradients in XRBs attractive [29].

If we look not at the stellar but the galactic level, the actual lack of X-ray binaries could be a marker, with the deficiency being a sign their energies are being exploited to some purpose. For that matter, high-energy flare activity from an individual star or the source of a gamma ray burst may point us at locations where an advanced civilization can use its technologies to deflect these energies to avoid the threat. If we push speculation to the extreme, we’re talking once again about Robert Forward territory, wondering whether environments like neutron stars can sustain their own kinds of life.

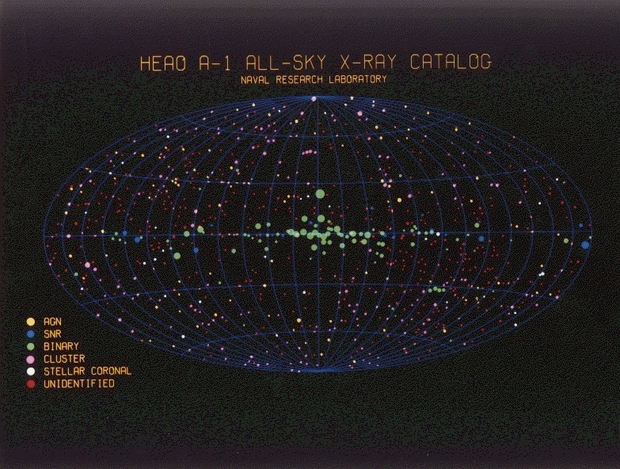

Image: HEAO-1 All-Sky X-ray Catalog: Beginning in 1977, NASA launched a series of very large scientific payloads called High Energy Astronomy Observatories (HEAO). The first of these missions, HEAO-1, carried NRL’s Large Area Sky Survey Experiment (LASS), consisting of 7 detectors. It surveyed the X-ray sky almost three times over the 0.2 keV – 10 MeV energy band and provided nearly constant monitoring of X-ray sources near the ecliptic poles. We’ve been examining high-energy targets for quite a while now and have numerous datasets to consult. Image credit: NASA.

Several things to keep in mind as we consider ideas that are on the face of things fantastic. First, the very practical fact that high-energy SETI need not be expensive, given our growing sophistication at using machine intelligence to analyze existing astronomical data (I’ve always nursed the wonderful idea that some day we’ll make a SETI detection and it will be corroborated by a century-old astronomical plate taken at Mt. Wilson Observatory). Second, existing facilities monitoring things like gamma ray bursts and detecting neutrinos are capable of full-sky monitoring and are doing good science. Our search for high-energy anomalies, then, takes a free ride on existing equipment.

So while it’s completely natural to find this approach well outside our normal ideas of astrobiology, their improbable nature should elicit a willingness to keep our eyes open. It would be absurd to miss something that has been in our data all along. And filtering incoming data as an add-on investigation into astrophysical processes may turn up anomalies that advance high-energy physics even if they never do resolve themselves into a SETI detection.

The paper is Lacki & DiKerby, “Possibilities for SETI at High Energy,” submitted for 2025 NASA DARES [Decadal Astrobiology Research and Exploration Strategy] RFI and available as a preprint.

SETI at the Extremes

Science fiction has always provoked interesting research. After all, many of the scientists I’ve spoken with over the years have been science fiction readers, some of whom trace their career choices to specific novels (Poul Anderson’s Tau Zero is frequently mentioned, but so is Frank Herbert’s Dune, and there are many others). This makes sense because there is a natural tension in exoplanet studies growing out of the fact that in most cases, we can’t even see our targets. Instead, we detect them through non-visual methods. True, we can analyze planetary atmospheres for some gas giant planets, but we’re only beginning to drill down to the kind of biosignature searches that may eventually flag the presence of life.

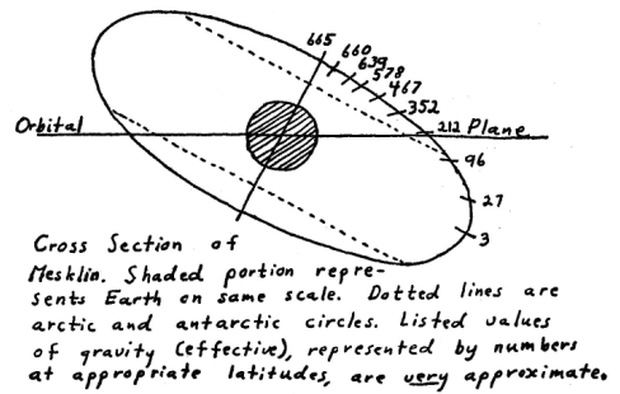

But fiction can paint a planet’s physics and visually explore its surface, modeling worlds in vast variety and sometimes spurring directions of thought that would otherwise remain unexplored. Consider Hal Clement, whose forays into planet-building included the remarkable Mesklin, a fast-rotating oblate world with an 18-minute day and surface gravity varying from 700 g at the poles to an almost bearable 3 g at the equator. Mission of Gravity, published as a serial in Astounding Science Fiction in 1953, involves an indigenous race’s interactions with a human crew at the equator. The encounter dazzled readers and led some into astrophysics.

These are unconventional aliens, and were particularly so in 1953, when communications between humans and tiny, flattened insect-like creatures seemed more at home in works of fantasy than what would become known as ‘hard science fiction’ (i.e., SF with a scrupulous reliance on proven physics). Clement’s novel was well received and spurred correspondence between the author and Robert Forward, who carried on the idea of extreme habitats in his novel Dragon’s Egg (1980). Both continued to ponder life in utterly extreme environments.

Gary Westfahl, the author of numerous titles of science fiction criticism including Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (McFarland, 2007) has dissected the hard science fiction genre in an essay in Science Fiction Studies. Westfahl makes the case that Mission of Gravity was “the first SF novel built on actual observational data involving another possible solar system.”

When I first read that, my thought was that it referred to Peter van de Kamp’s studies of Barnard’s Star at Swarthmore College’s Sproul Observatory in the 1930s and later. The detection of planets there proved erroneous, but so did a ‘detection’ at 61 Cygni. Clement seems to have used that supposed exoplanet as he modeled his world Mesklin. He wrote about his process in Astounding‘s issue of June, 1953 in which Mission of Gravity continued to be serialized.

I checked my collection of old magazines to find that issue, where he describes exactly how he built his planet. The details are fascinating, and available in some editions of Mission of Gravity. He’s not totally convinced that the 61 Cygni find is actually a planet — the object could not be seen, and the ‘detection’ was based on astrometry using photographs of this binary system. The paper, by Kaj Aage Strand, was painstaking, although the supposed planet turned out to be a chimera. Clement is not sure, but he accepts it as a planet for the purposes of the story: He writes:

If we assume the thing to be a planet, we find that a disk of the same reflecting power as Jupiter and three times his diameter would have an apparent magnitude of twenty-five or twenty-six in 61 C’s location; there would be no point looking for it with present equipment. It seems, then that there is no way to be sure whether it is a star or a planet, and I can call it whichever I like without too much fear of losing points in the game.

Image: Reproduction of diagrams by Hal Clement, originally published in his article “Whirligig World”, Astounding Science Fiction, June 1953. Top: Diagram of the cross-sectional shape of Mesklin, with approximate values for the effective surface gravity at various latitudes (in multiples of Earth gravity). The dashed lines are polar circles. The shaded circle in the middle represents the size of Earth on the same scale. Bottom: Diagram of Mesklin’s orbit, with approximate isotherms and times of crossing them. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

These days we have to say that the first novel built on observational data of other stellar systems would have to be limited to a time after 1992, which is when Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail found planets around the neutron star PSR B1257+12. Readers are welcome to name the novel (I don’t know the answer). This was, after all, the first time planets beyond our Sun were detected and confirmed, even if it would be another three years before we found 51 Pegasi b, the first planet around a main sequence star.

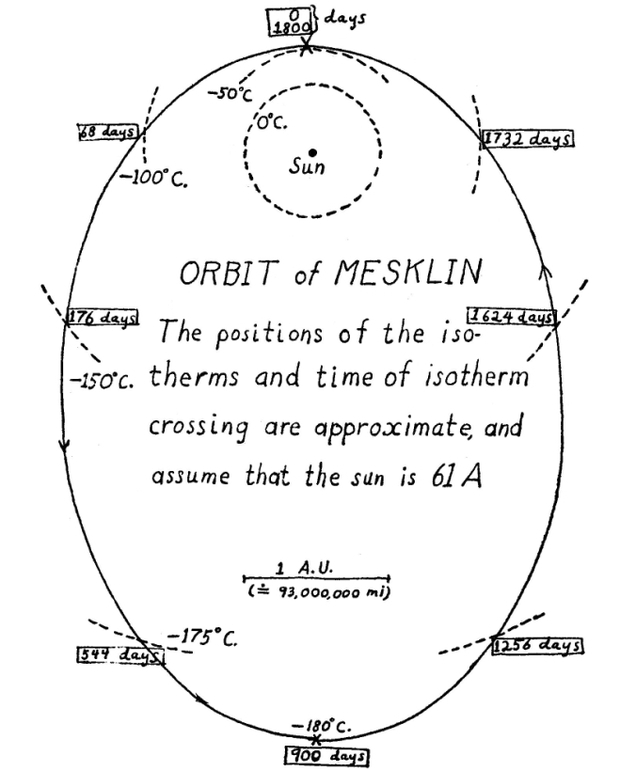

Robert Forward’s Dragon’s Egg takes astrobiology into even more extreme territory. He had been talking to Frank Drake, the first practitioner of SETI, who in 1973 was already thinking about life in highly unusual places, including settings on a neutron star. Let’s pause with Drake for a moment, because this is an interesting period in the history of science fictional ideas. Drake is quoted in Astronomy Magazine for December of 1973 as saying that life might well evolve in such a place.

In the exterior layers of these objects, we don’t have atoms…, but we do have atomic nuclei. And we have more varieties of atomic nuclei in a neutron star than we have varieties of atoms on our Earth. And from what we know of nuclear physics, those nuclei might combine together to form enormous supernuclei, or macronuclei, analogous to the large molecules which make up Earth life. And so as far as we know, it is possibly feasible to reproduce exactly the evolution which occurred on Earth but substituting for atoms and molecules, nuclei and macronuclei. So indeed there could be creatures on neutron stars that are made of nuclei. The temperatures are just right to make the required nuclear reactions go.

The combination of Clement’s planet Mesklin and Drake’s musings on neutron star life propelled Forward to re-examine the whole question and further refine Drake’s ideas. In Dragon’s Egg, the surface gravity on the neutron star is 67 billion times that of Earth. The local species is called the cheela, who are creatures the size of sesame seeds. The novel follows the development of their civilization from its earliest technologies to actual communications with a human-manned spacecraft in orbit around the star. For as the humans come to realize, the cheela experience the life and death of numerous generations in the span of mere hours.

So we see civilizational change in minutes. Forward had help with the structure of the novel from science fiction writer and editor Lester Del Ray, then working at Ballantine. He would eventually refer to the book as something of a textbook on neutron star physics “disguised as a novel.” None of that takes away from the sheer readability of this encounter with a species that within days achieves physics breakthroughs beyond those of the humans that are observing them. As with 1984’s Rocheworld, Forward’s prose is a bit clunky but his science is tight and his plot gripping.

Image: An combined image from multiple instruments showing a neutron star in the Small Magellanic Cloud. The reddish background image comes from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and reveals the wisps of gas forming the supernova remnant 1E 0102.2-7219 in green. The red ring with a dark centre is from the MUSE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope and the blue and purple images are from the NASA Chandra X-Ray Observatory. The blue spot at the centre of the red ring is an isolated neutron star with a weak magnetic field, the first identified outside the Milky Way. Credit: ESO/NASA, ESA and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)/F. Vogt et al. Acknowledgments: Mahdi Zamani.

We could go on with life in extreme environments as envisioned by science fiction (and I might mention Stephen Baxter’s Raft (Gollancz, 2018), where a rip in spacetime takes a human crew into a universe where the force of gravity is one billion times stronger than ours). Other readers will have their own favorites. I notice that some exoplanet and SETI researchers are following the lead of these novelists and taking a hard look at places we would consider hostile to any forms of life. As witness a recent paper from Brian Lacki and Stephen DiKerby on SETI at high energy levels.

And why not? We’re learning to think outside our usual preconceptions when it comes to habitability, and if we take seriously the idea of Kardashev Type II or III civilizations, we might well look for places where vast power resides in small spaces. Clément Vidal continues to make this point. Here the reference is his essential The Beginning and the End: The Meaning of Life in a Cosmological Perspective, Springer 2014. This is a key text for anyone serious about Dysonian SETI.

Can we learn to be as imaginative as some of the great science fiction authors? I think the wild variety of exoplanets thus far discovered demands that response from anyone pondering what might exist on everything from gas giant moons to desert worlds just barely touching the habitable zone. Keith Cooper gets into these questions in his fine Amazing Worlds of Science Fiction and Science Fact (Reaktion Books, 2025), where the link between the literature of the fantastic and cutting edge astrophysics is explicitly studied. I’ll be reviewing this one soon in these pages.

As to Lacki and DiKerby, they’re interested in exploring parts of the SETI landscape that have seen little attention. While our thinking about astrobiology naturally flows out of life as we already know it (and thus on Earth), what about those off-the-wall places where humans would instantly perish if they were so unwise as to get too near? Is a neutron star a SETI target? The accretion disk of a black hole? A binary X-ray pulsar?

We can posit strange lifeforms like those of Clement and Forward, but we can also add that places of high energy could be exploited by advanced civilizations that developed on far different worlds, cultures that are mining these high energy sources to drive civilizational projects whose intent may remain unfathomable. So without any knowledge of whether exotic life can be possible in, say, stellar plasma or on a neutron star’s surface, we might consider just what technosignatures would be possible if we found a culture at work in the places where the most extreme energies are available.

Lacki (University of Oxford) is part of the Breakthrough Listen team, while DiKerby is an astrophysicist at Michigan State University. I want to go through their paper next time as they push SETI concepts to the limit and ask what the result would look like.

The paper on high energy SETI is Lacki & DiKerby, “Possibilities for SETI at High Energy,” a white paper for NASA DARES (NASA Decadal Astrobiology Research and Exploration Strategy). Available here.

A Better Look at 3I/ATLAS

Just a short note, prompted by the release of new imagery of the intersellar object 3I/ATLAS by the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii. It’s startling how quickly we’ve moved from the first pinpoint images of this comet to what we see below, which draws on Gemini North’s Multi-Object Spectrograph to show us the tight (thus far) coma of the object, the gas and dust cloud enshrouding its nucleus. Changes here as the comet nears perihelion will teach us much about the object’s composition and size. Some early estimates have the cometary nucleus as large as 20 kilometers, considerably larger than both ‘Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov, the first two such objects detected. This is a figure that will doubtless be adjusted with continued observation.

Image: Using the Gemini North telescope, astronomers have captured 3I/ATLAS as it makes its temporary passage through our cosmic neighborhood. These observations will help scientists study the characteristics of this rare object’s origin, orbit, and composition. Credit: NSF NOIRLab.

3I/ATLAS also shows a more eccentric orbit than its predecessors. Remember that an eccentricity of 0 means an orbit that is completely circular, while as we move from 0 to 1, the orbit becomes drawn out, to the point where an orbit with eccentricity values of 1 or above doesn’t return to the Sun, but continues into interstellar space. The new comet’s orbital eccentricity is 6.2, considerably higher than ‘Oumuamua (1.2) and Borisov (3.6). Perihelion will come at the end of October at a distance of 210 million kilometers, which will place the object just inside the orbit of Mars. Amateur astronomers with a good telescope may just be able to get a glimpse of it late in 2025.

A New Horizons First for Interstellar Navigation

If you’re headed for another planet, celestial markers can keep your spacecraft properly oriented. Mariner 4 used Canopus, a bright star in the constellation Carina, as an attitude reference, its star tracker camera locking onto the star after its Sun sensor had locked onto the Sun. This was the first time a star had been used to provide second axis stabilization, its brightness (second brightest star in the sky) and its position well off the ecliptic making it an ideal referent.

The stars are, of course, a navigation tool par excellence. Mariners of the sea-faring kind have used celestial navigation for millennia, and I vividly remember a night training flight in upstate New York when my instructor switched off our instrument panel by pulling a fuse and told me to find my way home. I was forcefully reminded how far we’ve come from the days when the night sky truly was a celestial map for travelers. Fortunately, a few bright cities along the way made dead reckoning an easy way to get home that night. But I told myself I would learn to do better at stellar navigation. I can still hear my exasperated instructor as he pointed out one celestial marker: “For God’s sake, see that bright star? Park it over your left wingtip!”

Celestial navigation of various kinds can be done aboard a spacecraft, and the use of pulsars will help future deep space probes navigate autonomously. Until then, our methods rely heavily on ground-based installations. Delta-Differential One-Way Ranging (Delta-DOR or ∆DOR) can measure the angular location of a target spacecraft relative to a reference direction, the latter being determined by radio waves from a source like a quasar, whose angular position is well known. Only the downlink signal from the spacecraft is used in a precision technique that has been employed successfully on such missions as China’s Chang’e, ESA’s Rosetta and NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

The Deep Space Network and Delta-DOR can perform marvels in terms of the directional location of a spacecraft. But we’ve also just had a first in terms of autonomous navigation through the work of the New Horizons team. Without using radio tracking from Earth, the spacecraft has determined its distance and direction by examining images of star fields and the observed parallax effects. Wonderfully, the two stars that the team chose for this calculation were Wolf 359 and Proxima Centauri, two nearby red dwarfs of considerable interest.

The images in question were captured by New Horizons’ Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) and studied in relation to background stars. These twp stars are almost 90 degrees apart in the sky, allowing team scientists to flag New Horizons’ location. The LORRI instrument offers limited angular resolution and is here being used well outside the parameters for which it was designed, but even so, this first demonstration of autonomous navigation didn’t do badly, finding a distance close to the actual distance of the spacecraft when the images were taken, and a direction on the sky accurate to a patch about the size of the full Moon as seen from Earth. This is the largest parallax baseline ever taken, extending for over four billion miles. Higher resolution imagers, as reported in this JHU/APL report, should be able to do much better.

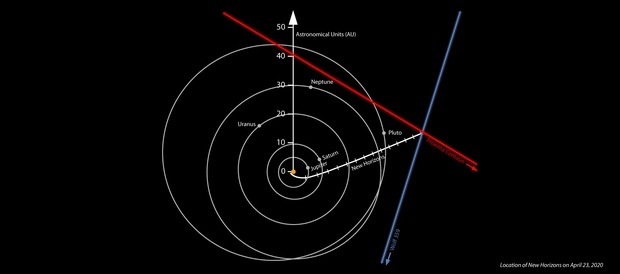

Image: Location of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft on April 23, 2020, derived from the spacecraft’s own images of the Proxima Centauri and Wolf 359 star fields. The positions of Proxima Centauri and Wolf 359 are strongly displaced compared to distant stars from where they are seen on Earth. The position of Proxima Centauri seen from New Horizons means the spacecraft must be somewhere on the red line, while the observed position of Wolf 359 means that the spacecraft must be somewhere on the blue line – putting New Horizons approximately where the two lines appear to “intersect” (in the real three dimensions involved, the lines don’t actually intersect, but do pass close to each other). The white line marks the accurate Deep Space Network-tracked trajectory of New Horizons since its launch in 2006. The lines on the New Horizons trajectory denote years since launch. The orbits of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto are shown. Distances are from the center of the solar system in astronomical units, where 1 AU is the average distance between the Sun and Earth. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/SwRI/Matthew Wallace.

Brian May, known for his guitar skills with the band Queen as well as his knowledge of astrophysics, helped to produce the images below that show the comparison between these stars as seen from Earth and from New Horizons. A co-author of the paper on this work, May adds:

“It could be argued that in astro-stereoscopy — 3D images of astronomical objects – NASA’s New Horizons team already leads the field, having delivered astounding stereoscopic images of both Pluto and the remote Kuiper Belt object Arrokoth. But the latest New Horizons stereoscopic experiment breaks all records. These photographs of Proxima Centauri and Wolf 359 – stars that are well-known to amateur astronomers and science fiction aficionados alike — employ the largest distance between viewpoints ever achieved in 180 years of stereoscopy!”

Here are two animations showing the parallax involving each star, with Proxima Centauri being the first image. Note how the star ‘jumps’ against background stars as the view from Earth is replaced by the view from New Horizons.

Image: In 2020, the New Horizons science team obtained images of the star fields around the nearby stars Proxima Centauri (top) and Wolf 359 (bottom) simultaneously from New Horizons and Earth. More recent and sophisticated analyses of the exact positions of the two stars in these images allowed the team to deduce New Horizons’ three-dimensional position relative to nearby stars – accomplishing the first use of stars imaged directly from a spacecraft to provide its navigational fix, and the first demonstration of interstellar navigation by any spacecraft on an interstellar trajectory. Credit: JHU/APL.

This result from New Horizons marks the first time that optical stellar astrometry has been applied to the navigation of a spacecraft, but it’s clear that our hitherto Earth-based methods of navigation in space will have to give way to on-board methods as we venture still farther out of the Solar System. Thus far the use of X-ray pulsars has been demonstrated only in Earth orbit, but it will surely be among the techniques employed. These rudimentary observations are likewise proof-of-concept whose accuracy will need dramatic improvement.

The paper notes the next steps in using parallactic measurements for autonomous navigation:

Considerably better performance should be possible using the cameras presently deployed on other interplanetary spacecraft, or contemplated for future missions. Telescopes with apertures plausibly larger than LORRI’s, with diffraction-limited optics, delivering images to Nyquist-sampled detectors [a highly accurate digital signal processing method], mounted on platforms with matching finepointing control, should be able to provide astrometry with few milli-arcsecond accuracy. Extrapolating from LORRI, position vectors with accuracy of 0.01 au should be possible in the near future.

The paper on this work is Lauer et al., “A Demonstration of Interstellar Navigation Using New Horizons,” accepted at The Astronomical Journal and available as a preprint.

3I/ATLAS: Observing and Modeling an Interstellar Newcomer

Let’s run through what we know about 3I/ATLAS, now accepted as the third interstellar object to be identified moving through the Solar System. It seems obvious not only that our increasingly powerful telescopes will continue to find these interlopers, but that they are out there in vast numbers. A calculation in 2018 by John Do, Michael Tucker and John Tonry (citation below) offers a number high enough to make these the most common macroscopic objects in the galaxy. But that may well depend on how they originate, a question of lively interest and one that continues to produce papers.

Let me draw on a just released preprint from Matthew Hopkins (University of Oxford) and colleagues that runs through the formation options. Pointing out that interstellar object (ISO) studies represent an entirely new field, they note that theoretical thinking about such things trended toward comets as the main source, an idea immediately confronted by ‘Oumuamua, which appeared inert even as it drew closer to the inner system and even appeared to accelerate as it departed. The controversy over its origin made 2I/Borisov a relatively tame object, it being clearly a comet. 3I/ATLAS looks a lot more like 2I/Borisov than ‘Oumuamua, though it’s larger than either.

Protoplanetary disks are a possible source of interstellar debris, but so for that matter are the Oort-like clouds that likely surround most main sequence stars, and that would largely be released when their hosts complete their evolution. ‘Oumuamua has been analyzed as a fragment of a small, outer-system world around another star, or even as a ‘hydrogen iceberg,’ and I see there is one paper suggesting that ISOs may be a part of galactic renewal, contributing their materials into protoplanetary disks and nascent planets.

The Hopkins paper underlines the ubiquity of such objects:

A standard picture has emerged, in which planetesimals formed within a protoplanetary disk are scattered by interactions with migrating planets or via stellar flybys, early in the history of a system (Fitzsimmons et al. 2023). The number density inferred from observations of the first two ISOs, in addition to studies of scattering in our own Solar System, suggest that such events are common, with ≳ 90% of planetesimals joining the ISO population (Jewitt & Seligman 2023). Such objects spread around the Milky Way’s disk in braided streams (Forbes et al. 2024), a small fraction of which intersect our Solar System. The observed ISO population is thus truly galactic, rather than being associated with local stars and stellar populations.

Image: ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) has obtained new images of 3I/ATLAS, an interstellar object discovered in recent weeks. Identified as a comet, 3I/ATLAS is only the third visitor from outside the Solar System ever found, after 1I/ʻOumuamua and 2I/Borisov. Its highly eccentric hyperbolic orbit, unlike that of objects in the Solar System, gave away its interstellar origin. In this image, several VLT observations have been overlaid, showing the comet as a series of dots that move towards the right of the image over the course of about 13 minutes on the night of 3 July 2025. The data were obtained with the FORS2 instrument, and are available in the ESO archive. Credit: European Southern Observatory.

I’m struck anew by how much our view of our Solar System’s place in the cosmos has changed. The size and density of the Kuiper Belt only swam into focus when the first KBO was discovered in 1992, although the belt had been hypothesized by Kenneth Edgeworth in the 1930s and Gerald Kuiper in 1951. The vast Oort Cloud of comets that envelops our entire system was posited by Jan Hendrik Oort in 1950. Now we’re looking at populations of objects at minute sub-planetary scale existing between the stars in unfathomable numbers.

Hopkins and team point out that the Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) will dramatically increase the number of confirmed ISOs. So then, what do we have on 3I/ATLAS? The early work on the object identifies it as a comet with a compact coma, a cloud of gas and dust surrounding the nucleus. It’s also bigger than its two predecessors, perhaps as large as 10 kilometers, as opposed to ‘Oumuamua and Borisov’s roughly 0.1 kilometers, although a more precise number will emerge as we learn more about its composition and albedo. It enters the Solar System at a higher speed than the latter ISOs, but one well within the distribution model used in this paper.

Interestingly, the object shows high vertical motion out of the plane of the galaxy, ruling out the idea that it comes from the same star as ‘Oumuamua or Borisov. That velocity points to an origin in the Milky Way’s thick disk – stars above and below the disk within which the Solar System resides. It is the first object to be identified as such. Says Hopkins:

“All non-interstellar comets such as Halley’s comet formed with our solar system, so are up to 4.5 billion years old. But interstellar visitors have the potential to be far older, and of those known about so far our statistical method suggests that 3I/ATLAS is very likely to be the oldest comet we have ever seen.”

The team’s model (based on Gaia data, disk chemistry and galactic dynamics) was developed during Hopkins’ doctoral research. It emerges as the first real-time application of predictive modelling to an interstellar comet. It likewise predicts that 3I/ATLAS will have a high water content. We’ll be able to check on that as observations continue. Co-author Michele Bannister, of the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, points out that 3I/ATLAS is already showing activity as it warms during its approach to the Sun. The gases the comet produces as it moves toward perihelion at 1.36 AU in October will tell us more.

The paper is Hopkins et al., “From a Different Star: 3I/ATLAS in the context of the ̄Otautahi–Oxford interstellar object population model,” submitted to Astrophysical Journal Letters and available as a preprint. The paper on the density of the interstellar object population is Do, Tucker & Tonry, “Interstellar Interlopers: Number Density and Origin of ‘Oumuamua-like Objects,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 855 (6 March 2018), L10. Full text. Also be aware of a new paper by Avi Loeb at Harvard that I haven’t yet had time to review. It’s “Comment on “Discovery and Preliminary Characterization of a Third Interstellar Object: 3I/ATLAS” (preprint).

New Model to Prioritize the Search for Exoplanet Life

Our recent focus on habitability addresses a significant problem. In order for astrobiologists to home in on the best targets for current and future telescopes, we need to be able to prioritize them in terms of the likelihood for life. I’ve often commented on how lazily the word ‘habitable’ is used in the popular press, but it’s likewise striking that its usage varies widely in the scientific literature. Alex Tolley today looks at a new paper offering a quantitative way to assess these matters, but the issues are thorny indeed. We lack, for instance, an accepted definition of life itself, and when discussing what can emerge on distant worlds, we sometimes choose different sets of variables. How closely do our assumptions track our own terrestrial model, and when may this not be applicable? Alex goes through the possibilities and offers some of his own as the hunt for an acceptable methodology continues.

by Alex Tolley

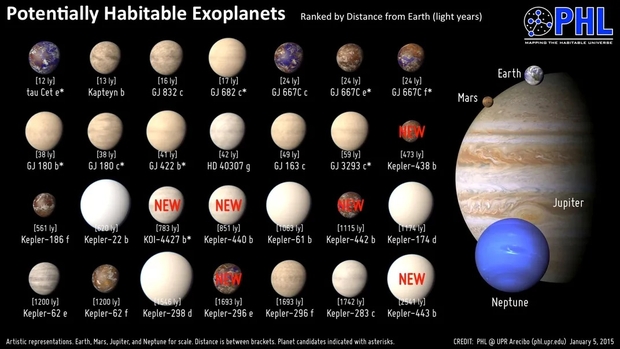

Artist illustrations of explanets in the habitable zone as of 2015. None appear to be illustrated as possible hanbitable worlds. This has changed in the last decade. Credit: PHL @ UPR Arecibo (phl.upr.edu) January 5, 2015 Source [1]

We now know that the galaxy is full of exoplanets, and many systems have rocky planets in their habitable zones (HZ). So how should we prioritize our searches to maximize our resources to confirm extraterrestrial life?

A new paper by Dániel Apai and colleagues of the Quantitative Habitability Science Working Group, a group within the Nexus for Exoplanet System Science (NExSS) initiative, looks at the problems hindering our quest to prioritize searches of the many possible life-bearing worlds discovered to date and continuing to be discovered with new telescope instruments.

The authors state that the problem we face in the search for life is:

“A critical step is the identification and characterization of potential habitats, both to guide the search and to interpret its results. However, a well-accepted, self-consistent, flexible, and quantitative terminology and method of assessment of habitability are lacking.”

The authors expend considerable space and effort itemizing the problems that have accrued: Astrobiologists and institutions have never defined “habitable” and “habitability” rigorously, even confounding “habitable” with “Habitable Zone” (HZ), and using “habitable” and “inhabited” almost interchangeably. They argue that this creates problems for astrobiologists when trying to plan how to develop strategies when determining which exoplanets are worth investigating and how. Therefore, defining terminology is important to avoid confusion. As the authors point out, researchers often assume that planets in the HZ should be habitable and those outside its boundaries uninhabitable, even though both assertions are untrue.

[I am not clear that the first assertion is claimed without caveats, for example, the planet must be rocky and not a gaseous world, such as a mini-Neptune.]

As our knowledge of exoplanets is data poor, it may not be possible to define whether a planet is habitable based on the available information, which leads to the imprecision of the term “habitable”. In addition, not only has “habitable” not been well-defined, but neither have the requirements for life been defined, which is more restrictive than the loose requirement for surface liquid water.

Ultimately, the root of the problem that hampers the community’s efforts to converge on a definition for habitability is that habitability depends on the requirements for life, and we do not have a widely agreed-upon definition for life.

The authors accept that a universal definition of life may not be possible, but that we can, however, determine the habitat requirements of particular forms of life.

The authors’ preferred solution is to model habitability with joint probability assessments of planetary conditions with already acquired data, and extended with new data. This retains some flexibility in the use of the term “habitable” in the light of new data.

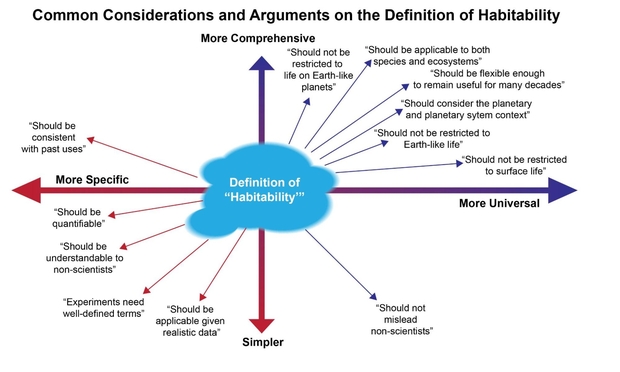

Figure 1 below illustrates the various qualitative approaches to defining habitability. Adhering to any single definition is not possible for a universal definition. The paper suggests that a better approach is to use quantitative methods that are both rigorous, yet flexible in the light of new data and information.

Figure 1. Various approaches to defining “habitable”. Any single definition for “habitability” fails to meet the majority of the requirements.

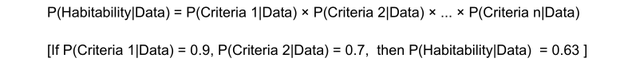

The equation below illustrates the idea of quantifying the probability of a planet’s habitability as a joint probability of the known criteria:

The authors use the joint probability of the planet being habitable. For example, it is in the HZ, is rocky, and has water vapor in the atmosphere. Clearly, under this approach, if water vapour cannot be detected, the probability of habitability declines to zero.

Perhaps of even greater importance, the group also looks at habitability based on whether a planet supports the requirements for known examples of terrestrial life, whose requirements vary considerably. For example, is there sufficient energy to support life? If there is no useful light from the parent star in the habitat, energy must be supplied by geological processes, leading to the likelihood that only anaerobic chemotrophs could live under those conditions, for example, as hypothesized in dark, glacial-covered subsurface oceans..

The authors include more carefully defined terms, including: Earth-like life. Rocky Planet, Earth-Sized Planet, Earth-Like Planet, Habitable Zone, Metabolisms, Viability Model, Suitable Habitat for X, and lastly Habitat Suitability which they defined as:

The measure of the overlap between the necessary environmental conditions for a metabolism and environmental conditions in the habitat.

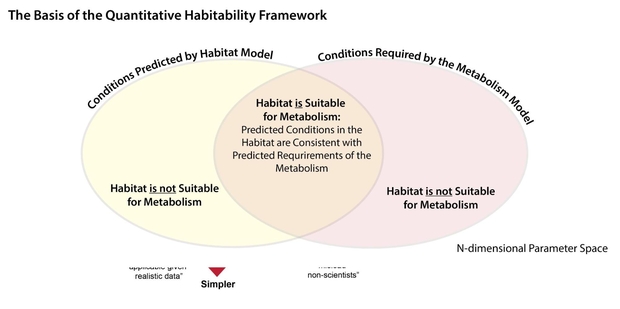

Because of the probability that life (at least some species of terrestrial life) will inhabit a planet, the authors suggest a framework where the Venn diagram of the probability of a planet being habitable intersects with the probability that the requirements are met for specific species of terrestrial life.

The Quantitative Habitability Framework (QHF) is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Illustration of the basis of the Framework for Habitability: The comparison of the environmental conditions predicted by the habitat model and the environmental conditions required by the metabolism model.

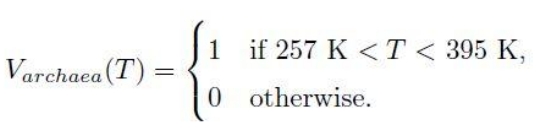

The probability of the viability of an organism for each variable is a binary value of 0 for non-viability and 1 for viability. For archaea and temperature, this is:

The equation means that the probability of viability of the archaea at temperature T in degrees Kelvin is 1 if the temperature is between 257 K ( -16 °C) and 395 K (122 °C). Otherwise 0 if the temperature is outside the viable range. (Ironically, this is imprecise, as it is for a species of archaean methanogen extremophile, not all archaeans.)

This approach is applied to other variables. If any variable probability is zero, the joint probability of viability becomes 0.

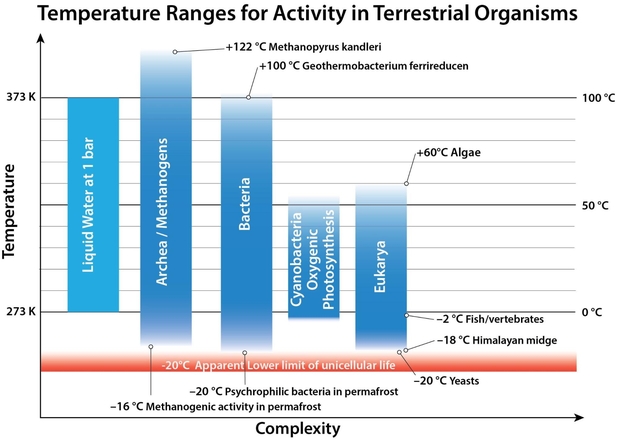

The figure below shows various terrestrial organism types, mostly unicellular, with their known temperature ranges for survival. The model therefore allows for some terrestrial organisms to be extant on an exoplanet, whilst others would not survive.

Figure 3. Examples of temperature ranges for different types of organisms, taken for species at the extreme ranges of survival in the laboratory.

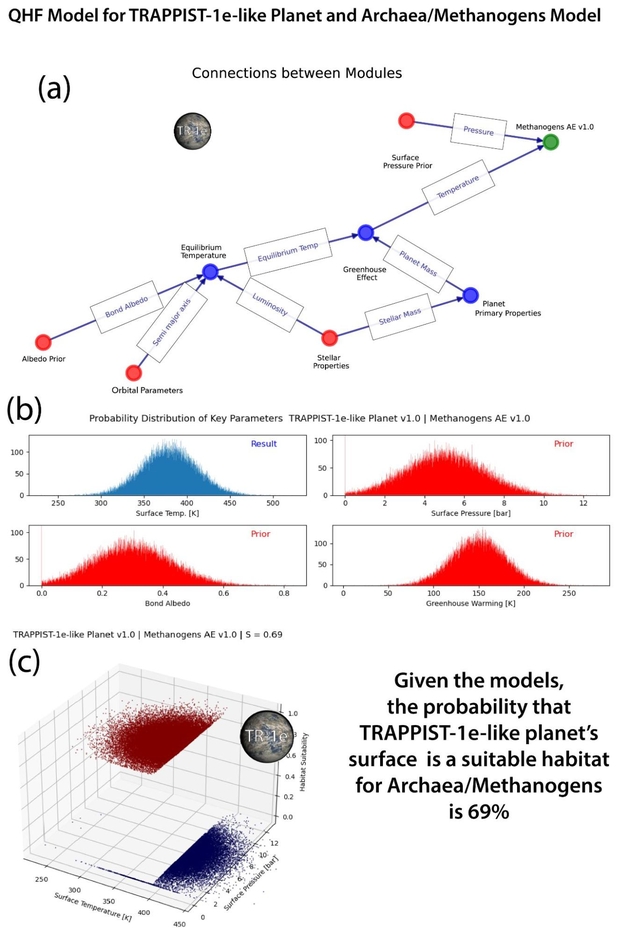

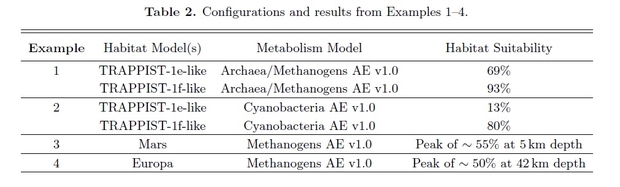

To demonstrate their framework, they work through models for archaean life on Trappist 1e and Trappist 1f, cyanobacteria on the same 2 planets, methanogens (that would include archaea) in the subsurface of Mars, and the subsurface ocean of Enceladus.

Figure 4 below shows the simplified model for archaea on Trappist 1e. The values and standard deviations used for the priors are not all explained in the text. For example, the mean surface pressure is set at 5 Bar for illustrative purposes, as no atmosphere has been detected for Trappist-1e. The network model for the various modules that determine the viability of an archaean is mapped in a). Only 2 variables, surface temperature and pressure, determine viability of the archaean prokaryotes in the modeled surface temperature. In more sophisticated models, this would be a multidimensional plot perhaps using principal component analysis (PCA) to show a 3D plot. The various assumed (prior) and calculated (result) values and their assumed distributions are shown as charts in b). The plot of viability (1) and non-viability (0) for surface temperature and pressure is shown in the 3D plot c. The distributions indicate the probability of suitability of the habitat.

Figure 4. QHF assessment of the viability of archaea/methanogens in a modeled TRAPPIST-1e-like planet’s surface habitat. a: Connections between the model modules. Red are priors, blue are calculated values, green is the viability model. b: Relative probability distributions of key parameters. c: The distribution of calculated viability as a function of surface temperature and pressure. The sharp temperature cutoff at 395K separates the habitat as viable or not.

The examples are then tabulated to show the probabilities of different unicellular life inhabiting the various example worlds.

As you can see, the archaea/methanogens on Trappist 1f have the highest probability of being present inhabiting that world if we assume terrestrial life represents good examples. Therefore, Trappist 1f would be prioritized given the information currently available. If spectral data suggested that there was no water in Trappist 1f’s atmosphere, this would reduce, and possibly eliminate, this world’s habitability probability, and with it the probability of it meeting the requirement of archaean life and hence reducing the overlap in the habitability and life requirement terms to nil.

My Critique of the Methodology

The value of this paper is that it goes beyond the usual “Is the exoplanet habitable?” with the usual caveats about habitability that apply under certain conditions, usually atmospheric pressure and composition. The habitable zone (HZ) around a star is calculated for the range of distances from the star where, with an ideal atmosphere composition and density, on a rocky surface, liquid water could be found. Thus, early Mars, with a denser atmosphere, could be habitable [2], and indeed, the evidence is that water was once present on the surface. Venus might also once have been habitable, positioned at the inner edge of our sun’s HZ, before a runaway greenhouse made the planet uninhabitable.

The concept of NASA’s “Follow the water” mantra is a first step, but this paper then points out this is only part of the equation when deciding the priority of expending resources on observing a prospective exoplanet for life. The Earth once had an anoxic atmosphere, making Lovelock’s early idea that gases in disequilibrium would indicate life, which quickly became interpreted as free oxygen (O2) and methane (CH4), largely irrelevant during this period before oxygenic photosynthesis changed the composition of the atmosphere.

Yet Earth was living within a few hundred million years after its birth, with organisms that predated the archaea and bacteria kingdoms [4]. Archaea are often methanogens, releasing CH4 into the early atmosphere at a rate exceeding that of geological serpentinization. Their habitat in the oceans must have been sufficiently temperate, albeit some are thermophilic, living in water up to 122 centigrade but under pressure to prevent boiling. If the habitability calculations include the important variables, then their methodology offers a rigorous way to determine the probability of particular terrestrial life on a prospective exoplanet.

The problem is whether the important variables are included. As we see with Venus, if the atmosphere was still Earthlike, then it might well be a prospective target. Therefore, an exoplanet on the inner edge of its star’s HZ might need to have its atmosphere modeled for stability, given the age of its star, to determine whether the atmosphere could still be earthlike and therefore support liquid water on the surface.

However, there may be other variables that we have repeatedly discussed on this website. Is the star stable or does it flare frequently? Does the star emit hard UV and X-rays that would destroy life on the surface by destroying organic molecules? Is the star’s spectrum suited for supporting photosynthesis, and if not, does it allow or prevent chemotrophs to survive? For complex life, is a large moon needed to keep the rotational axis relatively stable to prevent climate zones and circulation patterns from changing too drastically? Is the planet tidally locked, and if so, can life exist at the terminator, as we have no terrestrial examples to evaluate? The Ramirez paper [3] includes his modeling of Trappist 1e, using the expected synchronization of its rotation and orbital period, resulting in permanently hot and cold hemispheres.

While the authors suggest that the analysis can extend beyond species to ecosystems, and perhaps a biosphere, we really don’t know what the relevant variables are in most cases. Unicellular organisms are sometimes easily cultured in a laboratory, but most are not. We just don’t know what conditions they need, and whether these conditions exist on the exoplanet. It may be that the equation variables may be quite large, making the analyses too unwieldy to be worth doing to evaluate the probability of some terrestrial life form inhabiting the exoplanet.

A further critique is that organisms rarely can exist as pure cultures except in a laboratory setting with ideal culture media. Organisms in the wild exist in ecosystems, where different organisms contribute to the survival of others. For example, bacterial biofilms often comprise different species in layers allowing for different habitats to be supported, from anaerobes to aerobes.

The analysis gamely looks at life below the surface, such as lithophilic life 5 km below the surface of Mars, or ocean life in the subsurface Enceladan ocean. But even if the probability in either case was 100% that life was present, both environments are inaccessible compared to other determinants of life that we can observe with our telescopes. This would apply to icy moons of giant exoplanets, even if future landers established that life existed in both Europan and Enceladan subsurface oceans.

What about exoplanets that are not in near circular orbits, but more eccentric, like Brian Aldiss’ fictional “Heliconia”? How to evaluate their habitability? Or circumbinary planets where the 2 stars are creating differing instellation patterns as the planet orbits its close binary?. Lastly, can tidally locked exoplanets support life only at the terminator that supports the range of their known requirements, such as Ramirez’ modeling of Trappist 1e?

An average surface temperature does not cover either the extremes, for example the tropics and the poles, nor that water is at its densest at 277K (4 °C), ensuring that there is liquid water even when the surface is fully glaciated above an ocean. Interior heat can also ensure liquid water below an icy surface, and tidal heating can contribute to heating even on moons that have exhausted their radioactive elements. If the Gaia hypothesis is correct, then life can alter a planet to support life even under adverse conditions, stabilizing the biosphere environment. The range of surface temperatures is covered by the Gaussian distribution of temperatures as shown in Figure 4 b.

Lastly, while the joint probability model with Monte Carlo simulation to estimate the probability of an organism or ecosystem inhabiting the exoplanet is a relatively computationally lightweight model, it may not be the right approach with more variables added to the mix. The probabilities may be disjoint with a union of different subsets of variables with joint probabilities. In other words, rather than “and” intersections of planet and organism requirement probabilities, there may be an “or” union of probabilities. The modeled approach may prove brittle and fail, a known problem of such models, which can be alleviated to some extent by using only subsets of the variables. Another problem I foresee is that a planet with richer observational data may score more poorly than a planet with few data-supported variables, simply due to the joint probability model.

All of which makes me wonder if the approach really solves the terminology issue to prioritize exoplanet life searches, especially if a planet is both habitable and potentially inhabited. It is highly terrestrial-centric, as we would expect, as we have no other life to evaluate. If we find another life on Earth, as posited by Paul Davies’ “Shadow Biosphere,” [4] this methodology could be extended. But we cannot even determine the requirements of extinct animals and plants that have no living relatives, but flourished in earlier periods on Earth. Which species survived when Earth was a hothouse in the Carboniferous, or below the ice during the global glaciations? Where were those conditions outside the range of extant species? For example, post-glacial humans could not survive during the Eocene thermal maximum.

For me, this all boils down to whether this method can usefully help determine whether an exoplanet is worth observing for life. If an initial observation ruled out an atmosphere like any of those Earth has experienced in the last 4.5 billion years, should the search for life be immediately redirected to the next best target, or should further data be collected, perhaps to look for gases in disequilibrium? While I wouldn’t bet that Seager’s ‘MorningStar’ mission to look for life on Venus will find anything, if it did turn up microbes in the acidic atmosphere’s temperate zone, that would add a whole new set of possible organism requirements to evaluate, making Venus-like exoplanets viable targets for life searches. If we eventually find life on exoplanets with widely varying conditions, with ranges outside of terrestrial life, would the habitat analyses then have to test all known life from a catalog of planetary conditions?

But suppose this strategy fails, and we cannot detect life, for various reasons, including instrumentation limits? Then we should fall back on the method I last posted on, which reduces the probability of extant life on an exoplanet, but leaves open the possibility that life will eventually be detected.

The paper is Apai et al (2025)., “A Terminology and Quantitative Framework for Assessing the Habitability of Solar System and Extraterrestrial Worlds,” in press at Planetary Science Journal. Abstract.

References

1. Schulze-Makuch, D. (2015) Astronomers Just Doubled the Number of Potentially Habitable Planets. Smithsonian Magazine, 14 January 2015.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/astronomers-just-doubled-number-potentially-habitable-planets-180953898/

2. Seager, S. (2013) “Exoplanet Habitability,” Science 340, 577.

doi: 10.1126/science.1232226

3. Ramirez R., (2024). “A New 2D Energy Balance Model for Simulating the Climates of Rapidly and Slowly Rotating Terrestrial Planets,” The Planetary Science Journal 5:2 (17pp), January 2024

https://doi.org/10.3847/PSJ/ad0729

4. Tolley, A. (2024) “Our Earliest Ancestor Appeared Soon After Earth Formed” https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2024/08/28/our-earliest-ancestor-appeared-soon-after-earth-formed

5. Davies P. C. W. (2011) “Searching for a shadow biosphere on Earth as a test of the ‘cosmic imperative,” Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A.369624–632 http://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0235