Students now getting their degrees in astronomy and even postdocs working in the field have come along at a time when datasets are widely shared. It was not always so, as Alexander Szalay can attest. A professor of physics and astronomy at Johns Hopkins, Szalay was an early player in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, leading the design of the archive and becoming involved with the statistical tools needed to analyze its holdings.

Back in the 1990s, Szalay recalls in the Chronicle of Higher Education (thanks to Regina Oliver for the tip), the astronomy community had no tradition of making data from projects like the SDSS public. In fact, astronomy at the time was a more tightly controlled enterprise. Telescope time, as always, was difficult to get, and no scientist wants critical findings to be claimed by someone else. Szalay remembers that era and the changes that quickly followed:

One incident demonstrates the mood at the time. A young astronomer saw a dataset in a published journal and wanted to reanalyze it, so he asked his colleague for the numbers. The scholar who published the paper refused, so the junior scholar took the published scatterplot, guessed the numbers, and published his own analysis. The original scholar was so upset that he called for the second journal to retract the young scholar’s paper.

Mr. Szalay said that astronomers changed their minds once the first big datasets hit the Web, starting with some images from NASA, followed by the official release of the first Sloan survey results in 2000.

“Once they saw the first data release, and they also saw that it was easy to use, I think they started turning around,” he said.

The Science of Shared Datasets

Quick as it was, that change looks to be lasting, and the astronomy community was in the forefront of it. We are in the era of large, shared datasets, a fundamental change in the way science is done that maximizes computer resources on desktops around the world. We’ve all become familiar with projects like SETI@Home, but the Galaxy Zoo is broadening the notion of ‘crowd science,’ categorizing images from the same Sloan Digital Sky Survey that Szalay helped structure. The Galaxy Zoo is about active participation, asking volunteers to examine and categorize images. And now there’s a Moon Zoo that lets them devote computer time to the tiniest lunar features.

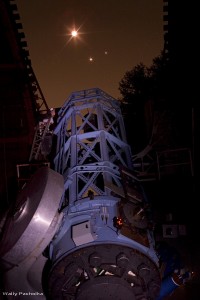

Image: The 60-inch reflector at Mount Wilson, built in an era when astronomy was a solitary profession. Credit and Copyright: Wally Pacholka (TWAN), courtesy Mike Simmons (AWB).

The word ‘crowdsourcing’ is one of those ungainly coinages so common in the computer era that come into existence because we have no other good way to describe a phenomenon. It’s spreading into biology (the Gene Map Annotator and Pathway Profiler) and, excitingly, into oceanography. There are interesting parallels between space exploration, biology and what goes on under the oceans, especially in the fact that huge amounts of data are becoming available for widespread use. From the article:

Another gush of data is happening deep in the Pacific Ocean, as a series of thousands of sensors strung along an underwater fiber-optic cable, along with new self-guided mobile sensors that can beam back data, promises to make oceanography the next field to embrace the data revolution and a crowd approach.

Mr. Lazowska, the computer scientist at the University of Washington who focuses on data-driven science, says that at the moment oceanography is “expeditional,” meaning that data are hard to come by because only a few organizations can afford the equipment to probe the depths. But new technologies, like those mobile sensors, promise to pipe in more data than scientists can manage without a shared database, like what the Sloan project did for astronomy.

Spreading Space Mission Science

We’ve seen these issues play out in the space community. Even when a mission is compromised, as Galileo was enroute to Jupiter when it was discovered that its high gain antenna could not be deployed, the data returned from its instruments take years to sort through, and will increasingly be handled by computers or armies of human volunteers. As for Szalay, he’s involved with an attempt to link large telescope datasets called the National Virtual Observatory. The emerging paradigm is all about putting eyes on data that used to be read by a single researcher. Papers emerge with more authors than ever listed and careers are shaped around building the tools to mine these data in powerful new ways.

Science archive centers for NASA mission datasets created the need for these developments and the digital sky surveys like Sloan and 2MASS demonstrated how online datasets could be tapped. The National Virtual Observatory concept emerged as early as 1999 and was fleshed out at a series of workshops and conferences leading to a 17-member organization that is building the needed infrastructure, along with a similar effort in Europe called the European Virtual Observatory. Here’s a description from the NVO materials available online:

The VO will enable a new way of doing astronomy, moving from an era of observations of small, carefully selected samples of objects in one or a few wavelength bands, to the use of multi-wavelength data for millions, if not billions of objects. Such datasets will allow researchers to discover subtle but significant patterns in statistically rich and unbiased databases, and to understand complex astrophysical systems through the comparison of data to numerical simulations. The VO will provide simultaneous access to multi-wavelength archives and advanced visualization and statistical analysis tools.

When the Galaxy Zoo came online in July of 2007, its server was swamped, and within 24 hours of launch, the site was receiving 70,000 galaxy classifications per hour, with more than 50 million received during the first year. Numerous projects are now in motion using these data (see the Zooniverse site for more). What’s exciting about the newly emerging initiatives is that, unlike SETI@Home, they demand active investigation by their audience, as opposed to simply letting a screensaver run when the PC is not otherwise in use.

The Quiet of the Mountaintop

I’ve written before in these pages about ‘Hanny’s Voorwerp,’ the unusual object now believed to be a gas cloud that was spotted by Dutch schoolteacher Hanny van Arkel. That was a Galaxy Zoo find, and van Arkel’s name is on papers about its significance in explaining the life cycle of quasars. These are exciting times for those with a good Net connection and a yen to participate in cutting-edge science. And as the Chronicle notes, Alexander Szalay, while a highly regarded astronomer, hasn’t looked through a telescope in almost ten years. Large-scale collaborations are moving to supplant the solitary scientist on a mountain top.

Image: Edwin Hubble at work in an era without computerized datasets. Credit: Mount Wilson Observatory.

Did I say ‘solitary’? Here’s a description of Edwin Hubble using the 100-inch instrument on Mt. Wilson, drawn from Elaine Bartusiak’s wonderful The Day We Found the Universe (Pantheon, 2009):

Observing with the 100-inch was a choreographed dance within the monumental dome a hundred feet high and nearly as wide. Sometimes Hubble could just lean back in a bentwood chair, his favorite, and serenely smoke his pipe in the darkness while taking a photograph. But other times he was perched high in the air on a platform that could adjust to any height via rails set on either side of the dome opening. With the telescope’s clock drive shifting the telescope as the nighttime sky slowly moved overhead, he and his assistant made sure the advance stayed in synchrony with Earth’s rotation… “This was the astronomical observing experience at its best,” noted Mount Wilson astronomer Allan Sandage, “a dark, quiet dome, a silently moving monster telescope, and mastery of the dangerous… platform, all in the interest of collecting data on a problem of transcendental significance.”

And if the night turned cloudy? Hubble said “You begin with the deskwork, later you turn to heavy reading, and later, to a detective story.” The solitary explorer on the mountaintop is a romantic vision that’s part of how we all conceive of astronomy, and it’s a glorious part of the science’s history, but in today’s world, the astronomer puts down the detective story and dips into the worldwide data flow.

“datasets are widely shared.”

And not just data sets but computer codes as well. My research would not be possible without all the data sets, tools and codes that get shared between experiments. All I can say is, thank heavens for NASA and all the data and codes they host for public use.

Hopefully the scientists who generate the datasets will get the appropriate credit for discoveries based on the data. This a subset of a larger issue that’s also occurring in software and really every creative field where content is easily shared — how do you make the content freely available to everyone who might use it, and at the same time make sure people are rewarded for their contributions?

Humanity is only really beginning to exploit the potential of the information revolution. Most of our institutions have not caught up with technology; it’s nice to see things changing in science.

As a high schooler I was lucky enough to get a personal tour of Palomar by Guido Munch (he was the nephew of our neighbor). I’ll always remember his description of how the observing platform’s rollers would stick, so that as the mount slowly shifted the platform would gradually become more and more tilted until suddenly with a squeak it would break loose and roll back into level, only to repeat the process ten or fifteen minutes later.

It’s unfortunate that this post didn’t generate more discussion, since it’s a large and multi-sided issue, e.g. the recent controversy involving the Kepler Mission team.

NS: If you’d like additional discussion from a decidedly different angle, you might enjoy this article and (some of) the attached comments:

http://www.techdirt.com/articles/20100525/1759369570.shtml

It is an attempt to contrast the relationship of amateur astronomers and journalists to their professional counterparts, and the synergies and conflicts that arise. Sharing of data and recognition are parts of the dynamic.

Thanks for the link, Ron S.

My take on the issue of shared scientific data is that it’s less about professionals vs. amateurs than about who gets the credit for discoveries, the data collectors or the data miners. If increasingly these are going to be separate functions than making sure they each get their due share becomes an issue. I don’t want a Dead Sea Scrolls situation where a small number of specialists monopolizes a unique dataset and excludes a lot of others who could make valuable contributions. Nor do I want people like (say) the Kepler Mission team who worked 20 years to get their spacecraft launched to miss out on the prestige of having discovered Earth-like planets, even if the actual detections are made by other scientists analyzing publically-released data sets. Maybe my concerns are groundless. But I would have liked more discussion of all this.