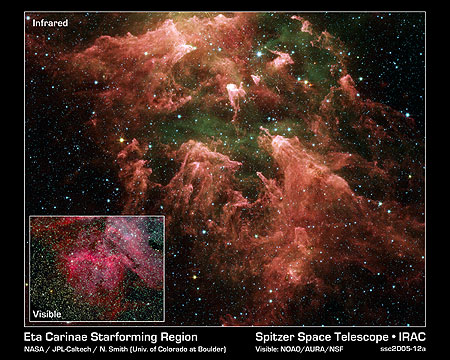

Panoramas this stunning deserve a lingering look (and be sure to click the image for a higher resolution view). You’re looking at more of the fruits of the Spitzer Space Telescope’s remarkable labors, this time a false-color image showing a part of the star-forming region known as the Carina Nebula. Using infrared, Spitzer was able to penetrate the so-called ‘South Pillar’ region of the nebula to reveal yellow and white stars in their infancy, wrapped up inside pillars of thick pink dust. The hottest gases here are green; the foreground stars are blue, which shows up better in the enlargement.

And note the bright area at the top of the frame, which is what this story is all about. The glow is caused by the massive star Eta Carinae, which is too bright to be observed by infrared telescopes. Stellar winds and ultraviolet radiation from this star are what have torn the gas cloud, leaving the tendrils and pillars visible here. It is this ‘shredding’ process that triggers the birth of the new stars Spitzer has revealed. And there is no doubt about what caused the shredding: Eta Carinae radiates energy at a rate five million times that of the Sun, making it the most luminous star known in the Milky Way. It also appears unstable; some scientists believe it is on the edge of becoming a supernova.

And note the bright area at the top of the frame, which is what this story is all about. The glow is caused by the massive star Eta Carinae, which is too bright to be observed by infrared telescopes. Stellar winds and ultraviolet radiation from this star are what have torn the gas cloud, leaving the tendrils and pillars visible here. It is this ‘shredding’ process that triggers the birth of the new stars Spitzer has revealed. And there is no doubt about what caused the shredding: Eta Carinae radiates energy at a rate five million times that of the Sun, making it the most luminous star known in the Milky Way. It also appears unstable; some scientists believe it is on the edge of becoming a supernova.

Image: This false-color image taken by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope shows the “South Pillar” region of the star-forming region called the Carina Nebula. Like cracking open a watermelon and finding its seeds, the infrared telescope “busted open” this murky cloud to reveal star embryos (yellow or white) tucked inside finger-like pillars of thick dust (pink). Hot gases are green and foreground stars are blue. Not all of the newfound star embryos can be easily spotted. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/N. Smith (University of Arizona).

“We knew that stars were forming in this region before, but Spitzer has shown us that the whole environment is swarming with embryonic stars of an unprecedented multitude of different masses and ages,” said Dr. Robert Gehrz, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, a member of the team that made the Spitzer observations.

Spitzer continues to set new standards for infrared observations. Photos of the area in visible light have revealed its finger-like dust pillars, but it took infrared to get inside the clouds to find the incubating stars. We can thus see how a mammoth star (Eta Carinae is 100 times the mass of our Sun) can spawn a new generation of stars. The Carina Nebula itself stretches across 200 light years; it has given birth to a number of mammoth stars which, in turn, have churned the cloud from which they emerged and caused it to collapse into new stars. Some believe our Sun came out of such an environment.

For a series of photographs of Eta Carinae in a variety of wavelengths from optical to x-ray and radio, see this page at the Chandra X-Ray Observatory site. A press release on the latest Spitzer work from the University of Colorado at Boulder is available here.

The periodicity of the eta Carinae events

Authors: A. Damineli (1), M. F. Corcoran (3 and 4), D. J. Hillier (2), O. Stahl (5), R. S. Levenhagen (1), N. V. Leister (1), J. H. Groh (1), M. Teodoro (1), J. F. Albacete Colombo (6), F. Gonzalez (7), J. Arias (8), H. Levato (7), M. Grosso (7), N. Morrell (9), R. Gamen (7), G. Wallerstein (10), V. Niemela (11) ((1) Instituto de Astronomia, Geofísica e Ciências Atmosféricas, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil (2) Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Pittsburgh, USA (3) CRESST and X-ray Astrophysics Laboratory, NASA/GSFC, USA (4) Universities Space Research Association, USA (5) ZAH, Landessternwarte, Germany (6) Facultad de Ciencias Astronomicas y Geofisicas de La Plata (FCAGLP) (7) Complejo Astronomico El Leoncito, Argentina (8) Departamento de Física, Universidad de La Serena, Chile (9) Las Campanas Observatory, Carnegie Observatories, Chile (10) Department of Astronomy, University of Washington, USA (11) In memoriam)

(Submitted on 27 Nov 2007)

Abstract: Extensive spectral observations of eta Carinae over the last cycle, and particularly around the 2003.5 low excitation event, have been obtained. The variability of both narrow and broad lines, when combined with data taken from two earlier cycles, reveal a common and well defined period. We have combined the cycle lengths derived from the many lines in the optical spectrum with those from broad-band X-rays, optical and near-infrared observations, and obtained a period length of 2022.7+-1.3 d.

Spectroscopic data collected during the last 60 years yield an average period of 2020+-4 d, consistent with the present day period. The period cannot have changed by more than $\Delta$P/P=0.0007 since 1948. This confirms the previous claims of a true, stable periodicity, and gives strong support to the binary scenario. We have used the disappearance of the narrow component of HeI 6678 to define the epoch of the Cycle 11 minimum, T_0=JD 2,452,819.8.

The next event is predicted to occur on 2009 January 11 (+-2 days). The dates for the start of the minimum in other spectral features and broad-bands is very close to this date, and have well determined time delays from the HeI epoch.

Comments: 9 pages, 4 EPS figures, submitted to MNRAS

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0711.4250v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Mairan Teodoro [view email]

[v1] Tue, 27 Nov 2007 14:14:18 GMT (93kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0711.4250

A multispectral view of the periodic events in eta Carinae

Authors: A. Damineli (1), D. J. Hillier (2), M. F. Corcoran (3 and 4), O. Stahl (5), J. H. Groh (1), J. Arias (8), M. Teodoro (1), N. Morrell (9), R. Gamen (7), F. Gonzalez (7), N. V. Leister (1), H. Levato (7), R. S. Levenhagen (1), M. Grosso (7), J. F. Albacete Colombo (6), G. Wallerstein (10) ((1) Instituto de Astronomia, Geofísica e Ciências Atmosféricas, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil (2) Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Pittsburgh, USA (3) CRESST and X-ray Astrophysics Laboratory, NASA/GSFC, USA (4) Universities Space Research Association, USA (5) ZAH, Landessternwarte, Germany (6) Facultad de Ciencias Astronomicas y Geofisicas de La Plata (FCAGLP) (7) Complejo Astronomico El Leoncito, Argentina (8) Departamento de Física, Universidad de La Serena, Chile (9) Las Campanas Observatory, Carnegie Observatories, Chile (10) Department of Astronomy, University of Washington, USA)

(Submitted on 27 Nov 2007)

Abstract: A full description of the 5.5-yr low excitation events in eta Carinae is presented. We show that they are not simple and brief, as thought before, but a combination of two components. The first, the `slow variation’ component, is revealed by slow changes in the ionization level of circumstellar matter across the whole cycle and is caused by the gradual immersion of the secondary star in the wind of the primary. The second, the `collapse’ component, is restricted to some months around the minimum, and is due to the immersion of the secondary deep in the primary wind. During this stage there is a general collapse of the wind-wind collision shock, and the Weigelt blobs are strongly shielded from high energy photons (E greater than 16 eV). High energy phenomena are sensitive only to the `collapse’, low energy only to the `slow variation’ and that of intermediate energy to both components. Simple eclipses and mechanisms effective only near periastron (e.g., shell ejection or accretion onto the secondary star) cannot account for the 5.5-yr cycle.

We find anti-correlated changes in the intensity and the radial velocity of P Cygni absorption profiles in FeII 6455 and HeI 7065 lines, indicating that the former is associated to the primary and the later to the secondary star. We present a set of light curves representative of the whole spectrum, indicating the spatial location where they are formed.

Comments: 14 pages, 6 EPS figures, submitted to MNRAS

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0711.4297v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Mairan Teodoro [view email]

[v1] Tue, 27 Nov 2007 16:33:48 GMT (170kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0711.4297