Back in 2007, science writer Lee Billings put together a panel for Seed Media Group on “The Future of the Vision for Space Exploration.” The session took place at the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill, and I remember flying to Washington with a bad head cold to moderate the event. Miraculously, my cold abated and I enjoyed the company of Louis Friedman (The Planetary Society), Steven Squyres (of Mars rover fame), Edward Belbruno (Princeton University) and interstellar guru Greg Matloff (CUNY). But I particularly remember conversations with Lee. I can’t say I was surprised to see him go on to emerge as one of the most gifted science writers now working.

Not long afterwards, Lee wrote an essay called The Long Shot for SEED Magazine that took him into the thick of the exoplanet hunt, from which this fine paragraph about the nearest stars and why they have such a hold on us:

Alpha Centauri is today what the Moon and Mars were to prior generations—something almost insurmountably far away, but still close enough to beckon the aspirational few who seek to dramatically extend the frontiers of human knowledge and achievement. For centuries, it has been a canonical target of the scientific quest to learn whether life and intelligence exist elsewhere. The history of that search is littered with cautionary tales of dreamers whose optimism blinded them to the humbling, frightful notion of a universe inscrutable, abandoned, and silent.

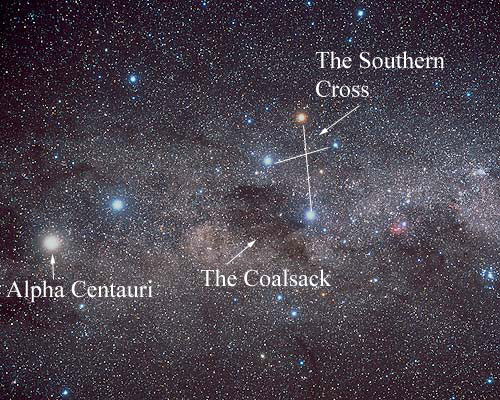

Image: Alpha Centauri and nearby stars. Notice that Centauri A, B and Proxima Centauri all appear as a single light source. Credit: Akira Fujii/David Malin.

I have to add my own cautionary note, that Billings and I share the view that intelligent life is rare in the galaxy, though I suspect that Lee would be as pleased to be proven wrong as I would. I mention all this because these topics will come up in detail in a book he is now working on called (with a nod to Gabriel García Márquez) Five Billion Years of Solitude, which starts with the search for planets like Earth but moves to a broader view that places our world in a cosmic context. As he did in the SEED essay, Billings spends time with some of the top scientists in the field, discussing the hunt for life elsewhere and explaining why his own optimism for the future of humanity has begun to dim.

Here my views diverge from his, but this excerpt from a recent interview Lee did with Steve Silberman is worth quoting to give a flavor of what’s coming in the book:

I now believe that while life may be widespread in the universe, creatures like us are probably uncommon, and technological societies are vanishingly rare, making the likelihood of contact remote at best. I am less confident than I once was that we will find unequivocal signs of life in other planetary systems within my lifetime. I believe that, when seen in the fullness of planetary time, our modern era will prove to have been the fulcrum about which the future of life turned for, at minimum, our entire solar system. I believe that we humans are probably the most fortunate species to have ever arisen on Earth, and that those of us now alive are profoundly privileged to live in what can objectively be considered a very special time. Finally, I would guess that though we possess the unique capacity to extend life and intelligence beyond Earth into unknown new horizons, there is a better-than-even chance that we will fail to do so.

We’ll have to await the book (it’s due out in 2013) to see how and why these ideas developed, but the interview with Silberman, done on the latter’s NeuroTribes blog, is wide-ranging and gets into the question of what would happen if we did indeed encounter a civilization more advanced than our own. Billings sets up three contact scenarios that are themselves cautionary, in that they remind us of the difficulty in establishing meaningful communication with an alien intelligence. It could be, for example, that differences in our two biospheres would be so profound that communication is all but impossible. Jacob Bronowski made much the same point in The Ascent of Man back in 1974, saying that evolutionary paths would not follow ours on different planets, and that it was conceivable that we wouldn’t recognize alien entities as intelligent or even alive.

So much for the ‘take me to your leader’ trope of early science fiction movies. Another possibility Billings examines is that intelligent aliens might be relatively similar to ourselves because of trends of convergent evolution (here Conway Morris inevitably comes to mind with his 2005 book Life’s Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe). This can be a troubling scenario as well given that competitive evolution could have produced creatures that, like ourselves, have become expert at conquering, manipulating and exploiting their native biosphere. In this case an alien encounter would not necessarily be benign and we should not assume good intentions.

But even a benevolent superior civilization could stir humanity’s kettle in dangerous ways, and our culture has been less imaginative than it should be in considering the philosophical and moral choices such an encounter could produce. From the interview:

If suddenly an Encyclopedia Galactica was beamed down from the heavens, containing the accumulated knowledge and history of one or more billion-year-old cosmic civilizations, would people still strive to make new scientific discoveries and develop new technologies? Imagine if solutions were suddenly presented to us for all the greatest problems of philosophy, mathematics, physics, astronomy, chemistry, and biology. Imagine if ready-made technologies were suddenly made available that could cure most illnesses, provide practically limitless clean energy, manufacture nearly any consumer good at the press of a button, or rapidly, precisely alter the human body and mind in any way the user saw fit. Imagine not only our world or our solar system but our entire galaxy made suddenly devoid of unknown frontiers. Whatever would become of us in that strange new existence is something I cannot fathom.

No one can fathom the result because it is utterly beyond our experience, leaving us to do what Billings does, which is to talk to the players who are pushing our knowledge forward and, using their insights, gain a perspective we can draw upon in the event of such a contact. Billings set out on a career in neuroscience but made a move into writing and journalism that allows him to range widely through the scientific disciplines in search of just that perspective. He mentions several writers who have been formative (Sagan, Stanislaw Lem), but to me his graceful, lapidary prose owes much to John McPhee. I suspect Five Billion Years of Solitude is going to be Lee’s breakthrough.

This is why astronomers would benefit from being spiritually intent.

If advanced tech came to us, and everything was “solved,” this would free us up to tackle the truths that are yet more subtle than the Higgs boson.

The existential challenge is to recognize that “knowledge of physicality,” is not total knowledge. Not even close…..and perhaps not actual knowledge in the least.

The silence of the singularity can be sussed out. That which math and physics cannot measure are yet actual.

Non-sense, yes, but not no-sense. There are truths that cannot be expressed but which are knowable. Ask Godel.

Logic can’t get to everywhere.

If an advance society comes to us and is not speaking about God, then RUN!

Hi Paul,

Thank you for writing up this interview on Centauri Dreams. I can’t think of a better venue, and your work has been a major inspiration for my own.

It’s perhaps a bit early yet, but I’d welcome any further discussion with you and your informed readership about this — it might prove interesting, for instance, to explore why and where our opinions diverge concerning what sort of extraterrestrial, extrasolar futures, if any, humans are most likely to make for themselves. Maybe it just comes down to simply seeing a glass as either half-full or half-empty. Of course, in the view of someone desiring a multi-planet mankind, one glass is simply too singular and fragile to suffice, regardless of how much water it can hold!

Cheers,

Lee

” Imagine if ready-made technologies were suddenly made available that could cure most illnesses, provide practically limitless clean energy, manufacture nearly any consumer good at the press of a button, or rapidly, precisely alter the human body and mind in any way the user saw fit. ”

Gosh, if all that happened, I would just return to women, wine, and music (art), probably in that order. No worries!

Interesting article. I can’t wait to pick up the book! A couple comments…

After reading various authors’ opinions, I also am becoming convinced that intelligent life is exceedingly rare in the universe. I’d guess that there are probably between 0 and 10 other examples of technological civilizations within our own galaxy at this time (probably skewed toward the lower-end). I wouldn’t think, however, that we’re absolutely alone in the entire universe, let alone in our own local group of galaxies — there’s just too many places for life to gain a foothold and, as far as I know, there’s nothing unique in nature.

The other thing I’d like to mention — about the possible forms of intelligent life we may one day encounter — is that I would bet on meeting something more similar to ourselves than not. (Not as in human-like or humanoid, but something that we can recognize as being alive and that has a body plan that makes sense.) We’re all obviously aware of the enormous variety of forms that life can take on, but, they’re not just randomly chosen to be that way. Sometimes people can forget that the “selection” part of evolution isn’t random at all. Each form exists because of its ability to survive and reproduce in a given environment at a specific time. So, whatever life forms we may one day encounter must be practical in some sense of the word — that is, at one time their bodies had to solve real-world, not abstract, problems (namely getting food/energy, escaping danger, and surviving long enough to reproduce).

PS – is the caption on the image correct? I found a similar photo that indicates that Proxima Centauri is visibly separated from Centauri A/B, albeit the author’s name is “Skatebiker”. See here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Alpha,_Beta_and_Proxima_Centauri.jpg

People (men) with absolute power or obscene levels of wealth are rarely nice. Humanity without limits (given the Encyclopedia Galactica scenario) would probably be inclined to hurt itself. Although Iain M. Banks paints a more benign picture of such a civilisation in his Culture novels…

Scott G. writes:

Scott, you’re right that Proxima is visibly separated from A and B, but I can’t pick it out at this level of detail. My caption, though, may have been better stated as something like: ‘Notice that Centauri A and B appear as a single light source here,’ etc.

I believe that an Encyclopedia Galactica would actually spur technological research…in a good way. Why? Because a truly advanced civilization’s technology is likely to be beyond our capabilities to reproduce. What if you presented a book on building integrated circuits to a bright New Guinean native and told him to go and build one? Even with step by step diagrams and pictures, he still wouldn’t be able to do so. Just because you know something is doable, that doesn’t mean you can do it. Witness the discussion on interstellar travel…we know, probably with great certainty, that an Orion-like nuclear bomb driven star ship would work…but that doesn’t mean we could build it today, everything being equal. If we tried, we would discover all sorts of new things that we never anticipated and which likely would not be noted in a set of instruction manuals from the local galactic federation. Star Trek, The Next Generation explored this notion, I believe, when the Ferengi stole a replicator from the Enterprise and killed themselves trying to build a copy.

I think the dangers of contamination are greatly over-stated. And, unlike Lee, I think there are reasons to be very optimistic about the future of the human race. What is happening now is that a good chunk of the world’s population is being dragged into the 21st Century. If you happen to be starting from the 6th century or worse, from the hunter-gatherer/tribal era of human development, it is a significantly painful thing to do, but it will happen. What exacerbates this is that the 21st Century is changing faster than any previous century, so the second and third worlds are chasing a moving target. However, there is good reason to suppose that this will all even out in the not too distant future. Unless this generation blows itself up, succeeding generations will tend to get along better simply because information technology is providing a common foundation for understanding that our generation and previous generations never had.

So…bring on the encyclopedia…I want it just to look at the pictures!! :-)

Mike

Lee Billings writes:

How true! And a major motivation for most of us as we look toward a future extending out into the Solar System and beyond.

At this point, the proclaiming that intelligent life is incredibly rare in the universe is a bit like a child proclaiming there are not fish in the ocean, because she scooped up one cup full of water and sees not fish within it. This is further complicated by the fact that we can’t know exactly what evolutionary path life could take on another planet, so we can’t be certain exactly what signs to look for.

No, we probably should not assume good intentions. Distances between stars are so great, it seems unlikely that another planet would declare war on Earth. However, if the aliens develop interstellar travel, we can’t rule out the possibility that the crew of an alien worldship or starship would prove hostile to our presence. They might even be determined to wipe out any species that could compete with them. Industrial expansion requires mass and energy, yet the galaxy is mostly vacuum. While we would hope that star civilizations will agree to cooperate and share the vast resources of the galaxy, it is also possible to imagine that solar civilizations will engage in intense competition for nearby star systems.

I suspect that if a “Encyclopedia Galactica” were suddenly beamed down, we would have some difficulty reaping the benefits of it. First off, we probably couldn’t even decipher it without some sort of key- we could be worse off trying to decipher alien messages than we are trying to read Linear A. Even if we could decipher it, the challenge of understanding and replicating the technology within would be epic indeed. Imagine how a Victorian scientists might feel if suddenly gifted with a PC or nuclear reactor- he would be hard pressed to work out the function of either, let alone to explain what happened when he removed the neutron moderator rods for further study!! We could encounter similar perils while playing with alien nanotechnology, or we may just find ourselves staring at all the pretty pictures, wondering what they represent.

If we recovered an alien “Encyclopedia Galactica”, we would have a new challenge- understanding it and building the technologies described within. Furthermore, the alien’s knowledge would probably NOT be absolute, and there would be mysteries for them to contemplate- and us, once we understand much of what they shared with us.

Gaining new technology and knowledge is probably one of the best outcomes from alien contact. As history shows, many times native cultures adapted well and quickly to new technologies (i.e., the Native Americans and horses), and technology is a great equalizing factor. Only when people are gifted with technology they cannot replicate themselves, making them reliant on foreign trade, does new technology tend to be harmful. Aliens might have their own reasons to want to keep their technology out of our hands, of course…

At this point, this is all speculation. It will prove more fruitful, in the long term, to focus on finding ways to answer the questions- continuing the ongoing hunt for exoplanets, searching for new ways to detect hypothetical alien civilizations, and working on the issues surrounding interstellar probes and starships. No one on Earth today knows if and where the aliens are, or what they are doing.

“Maybe it just comes down to simply seeing a glass as either half-full or half-empty.”

It is neither. The problem , in it’s essence, is that the glass gets further and further away making it contents more and more fuzzy.

Anytime I see a discussion like this I want to ask … what are the error bars?

I have been interested in discussions like this for 50 years , one thing colors my thought, that is reading prose science fiction over that period time. One lesson that I have come to embrace is that the body of knowledge we know as human history is almost , for sure, useless in trying predict the future of a complex technological society. We have reached a point on the arc of civilization where history does not repeat itself.

In any case I think it impossible to predict what even human civilization will be like in 500 years.

If someone puts forward a model of our future it should always be given with well defined standard deviations.

“No one on Earth today knows if and where the aliens are, or what they are doing.”

Who knows, some of them may be commenting on Earthly blogs, like this one, just for the lulz.

At the 100 Year Starship Symposium last month in Houston, I asked Dr. Jill Tarter of SETI how humanity can prepare itself for the eventual (possible? inevitable?) discovery of extraterrestrial life. She stressed STEM education – wherever, whenever and everywhere possible. While I agree on the importance of STEM, as a cultural historian who teaches critical/creative thinking courses, I feel as a society we lack imagination. And it is imagination that we will need when that day of first contact comes because the very existence of extraterrestrial life will challenge our most basic myths of creation and destiny, our self-assurances of human exceptionalism and our beliefs in a human-centered universe. Just as the shift from an Earth to a Sun-centered worldview was culturally traumatic, so too may be the shift that (hopefully!) awaits us. While it is impossible to completely anticipate the cultural impact of first contact (not to mention the military or political!), I find the challenge of doing so irresistibly fascinating.

Can’t help but feel that the problem with a paradox such as Fermi’s is that it is telling us there is an error somewhere in our data or assumptions. At the moment the consensus view feels rather anthropocentric but we shall have to see how the data develops before resolving this one of course.

Edg Duveyoung said on October 10, 2012 at 11:37:

“This is why astronomers would benefit from being spiritually intent.

“If advanced tech came to us, and everything was “solved,” this would free us up to tackle the truths that are yet more subtle than the Higgs boson.”

LJK replies:

How many humans out of the over 7 billion members on this planet would actually be engaged in this activity, by necessity or otherwise? There is a reason that scholars and monks are so few in comparison to the rest of our species. Personally I imagine most people would go off and party indefinitely, as even one commenter in this thread already said he would do if such a thing ever came to pass.

Though ironically I do agree with you that most professional astronomers do need be a bit more spiritual and wider-minded when it comes to the subject of their study. Though between the heavy competition for telescope time and the dwindling budgets for science, I can understand why the professional members of the field are often focused on career survival first.

Edg then said:

“The existential challenge is to recognize that “knowledge of physicality,” is not total knowledge. Not even close…..and perhaps not actual knowledge in the least.” And etc….

LJK replies:

Yep,. we already know that science does not hold all the answers. Nor does anyone with a level head on the matter think or state that science is the final word on Existence, certainly not any time soon. However, that does not mean that science is wrong or misguided fundamentally.

This attitude of “There are more things in Heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy, Horatio” may make the one who says this sound like they know some deep secret of the Cosmos privy to few others, but it is merely stating what any competent person already knows and ends up weakening the position that science has taken so long to attain and has done so much to pull us out of the cultural and intellectual gutter. Plus it is old and boring.

Edg finally says:

“If an advance society comes to us and is not speaking about God, then RUN!”

LJK replies:

So what would this advanced ETI have to say exactly to make us want to flee? Could we actually escape or even defend ourselves against beings who can make interstellar journeys? Personally I would be very concerned if they came to promote their deity or equivalent supernatural being which they venerated, especially if they weren’t big on taking No for an answer.

Kathleen Toerpe said on October 11, 2012 at 2:00:

“Just as the shift from an Earth to a Sun-centered worldview was culturally traumatic, so too may be the shift that (hopefully!) awaits us. While it is impossible to completely anticipate the cultural impact of first contact (not to mention the military or political!), I find the challenge of doing so irresistibly fascinating.”

Humanity definitely needs a cultural shock/awakening and soon! We are still living in our celestial cradle, making it more foul and reducing its limited resources with each passing day. Either an ETI has to come along and invite us into the Galactic Federation, or we have to start expanding into the Sol system ourselves. By expanding I am not just referring to a physical meaning.

See here for another take on this subject of how cosmic awareness is the key to our survival and evolution:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=23526

And we definitely need more cultural historians and professionals of related fields like yourself when it comes to SETI and its related fields!

Ron S said on October 10, 2012 at 23:12:

“No one on Earth today knows if and where the aliens are, or what they are doing.”

“Who knows, some of them may be commenting on Earthly blogs, like this one, just for the lulz.”

This is the very theme of the late Dr. Allen Tough, who created a Web site inviting any alien beings who are tapped into our Internet to say howdy (and hopefully a bit more than that):

http://www.ieti.org/

As for the idea that an advanced ETI is beaming their equivalent of the Encyclopedia Galactica to every corner of the galaxy out of some sense of literally universal altruism and cosmic uplifting: I find it about as likely as a rich person just deciding to give away all of his or her wealth by tossing their money out the upper window of a skyscraper to the masses on the street far below. Or giving random strangers the keys to their mansion and letting them help themselves to the possessions inside.

About the only time this ever happens is if the rich person has gone mentally unbalanced, decides they have enough funds to make careful donations (and getting a major tax writeoff in the process), or are dying and finally figured out they cannot take it with them. Even then the wealth usually goes straight to his or her relatives, not necessarily those who are needy or deserving of it.

As for this latter idea, I have posited before based on such SF novels as James Gunn’s The Listeners that an ETI which is facing some imminent demise might want to preserve itself culturally by beaming its vast knowledge to others with the added benefit of improving the recipient society so at the very least the receivers could secure and maintain the senders’ heritage in some relevant form.

Otherwise I cannot see why an ETI would just give away its undoubtedly hard-earned knowledge and technology blindly into space, especially since it could be used against them one day. Unless these beings are already so advanced and so secure that making others smarter and stronger would not matter to them.

In any event, as we have seen multiple times with our society, no one would undertake a large and long-term project like the Benfords’ Beacon METI without the senders ensuring that they would be the higher benefactors of this action. This includes the idea that they are attempting to preserve their society before extinction.

I tend to sit on my hands when comment threads like this one come up (other than some light humor, perhaps). That said, I can be most concise by pressing the virtual “like” button on the above comments by Al and Larry.

@Ron:

@ljk: An advanced society beaming its knowledge to the universe is not inconceivable. There is the pride felt by a scientist when he figures out some secret of the universe and can tell others.

In fact, there is a clear example of such sharing here on earth. The various preprint servers have numerous scientific articles that can be accessed for free. Admittedly, you will not find the instructions there on how to build a B2 bomber, but there is plenty of basic research that is shared at no profit to the researcher beyond professional stature.

Troy said on October 12, 2012 at 18:13:

“@ljk: An advanced society beaming its knowledge to the universe is not inconceivable. There is the pride felt by a scientist when he figures out some secret of the universe and can tell others.”

Yes, but will the powers-that-be allow the scientists to actually do this?

I am willing to bet that political leaders are basically the same everywhere: Paranoid to remain in power and not allow the potentially superior beings of another world to upset their domain.

To add to my previous statement: Of course if ETI turn out to be anything like us (and most of our SETI programs by their very nature and limitations are aimed at finding species similar to us in behavior at least), their exuberant scientists and other citizens with access to a radio telescope or a giant pulsed laser will find ways to get around any restrictions if they really want to crow about their accomplishments and themselves to the rest of the galaxy.

Such behaviors have already happened here despite numerous warnings and protests. They will continue to happen, up to and including groups of like-minded folks bodily leaving the Sol system for other sections of the Milky Way galaxy because human nature and life on this planet in general has a habit of striking out for new places to live, especially when things are getting rough in the old neighborhood.

If ETI are anything like life on Earth, then the first signals or even beings we encounter may be these very kinds of rouges who thumb their noses at the rest of their kind. Whether this will be good for us and vice versa remains to be seen, but it does tend to be those who buck social norms and trends who make things happen. SETI and interstellar travel is not and will not be excluded from this rule – and I cannot wait to see if it is literally universal or not.