What It Means to be Human Without Earth: Existential Horror and Hope in Aniara

By Larry KlaesAniara – A Review by Larry Klaes

In the summer of 2018, I took a vacation with my family on an ocean cruise. Being on that cruise ship was very much like being in a small city – minus any vehicles larger than a forklift truck – with just about anything you might want only a stroll away, unless you asked someone to bring the desired item to your cabin.

With just a little effort, you could even avoid and outright ignore the vast watery expanse just outside the confines of your ship with only a little effort if you so desired. Often, I was reminded of being in a large and expensive shopping mall of the kind usually found on dry land. The ship was so big, in fact, that in many instances one barely even noticed when the ocean was moving beneath and around you.

One of the many things this vacation offered was a chance to meet and talk with the cruise ship’s captain and first officers. This was an opportunity for the passengers to ask the chief crew personnel just about anything related to the ship and their roles within it.

On that day several hundred of us sat in a large auditorium and addressed our questions to the captain and his officers, who were seated on the stage before us. I cannot say I recall anything particularly noteworthy from the questions the various passengers asked the captain or his replies to them, other than I thought that most of their queries probably could have been answered with a brief Internet search. But what fun would that have been, am I right?

When my opportunity arose, I decided upon a question I had kept in my mind for a long time, not only for the officers of this cruise ship but for all similar venues and situations…

If a nuclear war suddenly happened during a cruise and the ship and its thousands of passengers were in such a place that they survived the initial attack, what would the crew do next?

As you might imagine, the captain was definitely taken aback by my inquiry. It was quite obvious that he did not expect such a question, certainly not from a guest on a pleasure cruise where a passenger’s most difficult issue would be where to get a really good tan or what time dinner is served. It was also plain that he himself had never contemplated such a scenario, either personally or in his official line of work.

The captain simply replied that everything would be alright. However, from his facial expression, it was clear to me at least that he really did not have any idea what would happen to his ship and those under his command should a nuclear holocaust ever take place while he was at sea. Like many who grew up during the Cold War, we often just assumed a nuclear war would either never happen, or if it did, then most of us would not survive the conflict long enough to imagine what we would do after the main event.

I was not entirely surprised that this captain would have not previously even entertained the idea, or that the cruise line company had ever addressed this contingency to their many employees. Nevertheless, I honestly held the hope that this thought and concern would now be implanted in his mind. In this manner, should the unthinkable ever come to pass, by that time this captain would have given his situation some concrete thought and put into plan some action that might save the lives of several thousand human beings while billions of others would not be so fortunate.

Or, if not this particular fellow, then perhaps other ship captains, including vessels in addition to maritime ones, had contemplated what they would do if global thermonuclear war broke out while they were on duty and taken personal action to save their charges.

COMMENT: As mine was the last question of this Question and Answer (Q&A) session, I soon joined the audience in getting up to exit the auditorium. Behind me had sat a young woman who then turned to her companion and said regarding my comment “What a question!” While I wasn’t sure if she knew I could hear her or if she even cared that I did, her reaction emphasized that people come on cruises to push away the typical worldly cares of our modern society and have their idea of fun. Mentions of nuclear conflict and its aftermath along with a dose of existentialism are among those topics that just do not tend to generate obscene amounts of money for cruise lines.

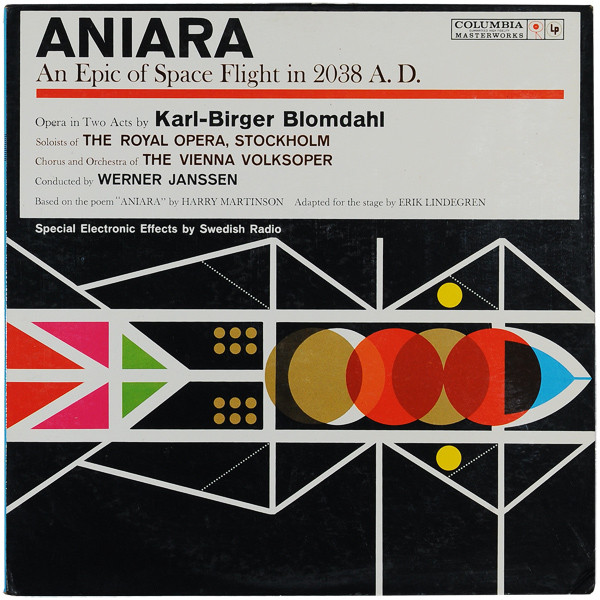

Unbeknownst to me at the time, just a few months before my ocean voyage and my fateful question to that captain, a Swedish film premiered at the 43rd annual Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) titled Aniara. Based on a famous epic poem of science fiction published in 1956 by Swedish author Harry Martinson (1904-1978), who in 1974 won a joint Nobel Prize in Literature with fellow Swede Eyvind Johnson (1900-1976) “for writings that catch the dewdrop and reflect the cosmos,” the cinematic Aniara closely follows Martinson’s poem…

In an unnamed future era, a vast spaceship transporting thousands of people from an Earth ecologically ruined by humanity to a new life on the neighboring planet Mars suffers an unprecedented accident that sends the vessel careening out of control into deep space. With no way to get back onto their original course or the hope for a rescue of any kind, the Aniara plunges into the void with its hapless passengers who must now face the fact that this ship is their permanent and final home.

Let us just say that things do not either go or end well for the crew and passengers of the Aniara on their unplanned voyage into the very Final Frontier.

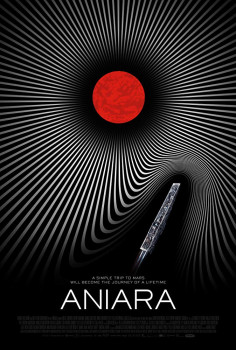

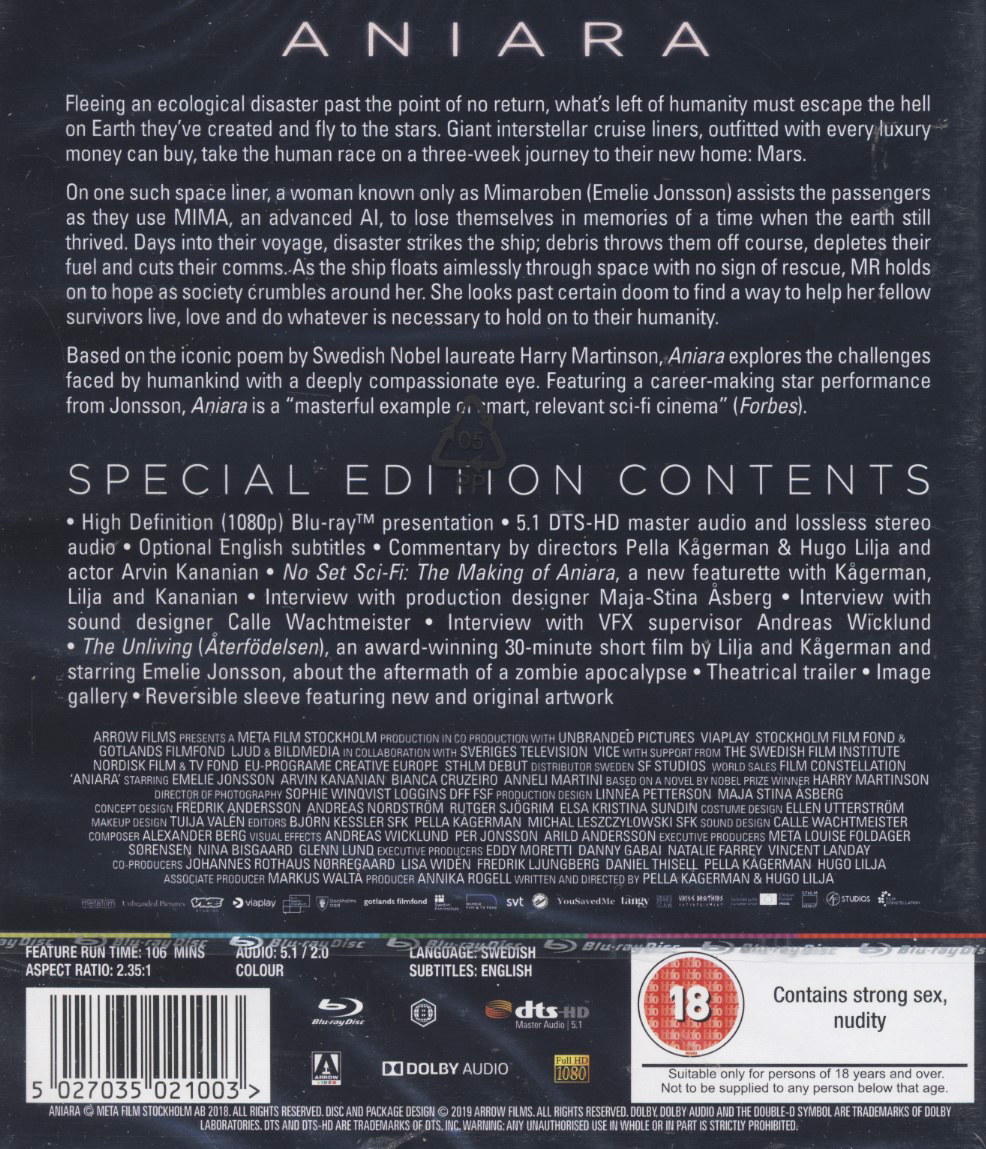

FIGURE LINK and CAPTION: The official film poster for Aniara. As you will find in detail later in this essay, it is but one of a surprising number of varied posters made to promote this film.

Welcome to Angst Science Fiction

“Good science fiction doesn’t have safe spaces.” – Mark Pontin

I became aware of Aniara shortly after its premieres in Sweden in 2018 and the United States in 2019. However, at the time I was not particularly compelled to seek it out, for Aniara felt like one of those films made by people who were neither writers nor fans of science fiction and only saw the genre as a way to express very terrestrial ideas and agendas couched in the palatable clothing of science fiction, one which many to this day do not take as seriously as they should.

I assumed any science in this category of fiction would be merely a combination of window dressing and vaguely designed machinations for the real story the makers were trying to say. One example of this which I wrote about was on the film Interstellar from 2014, where producer Christopher Nolan (born 1970) made an attempt to be the next Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999). You may read my essay here:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2014/12/19/interstellar-herald-to-the-stars-or-a-sirens-song/

To be even more specific, I give you the following quote from writer-director Michael Kuciak reviewing Aniara for Final Draft, a company that produces software for writing screenplays:

“Script-wise, Aniara tangentially fits a sub-sub-sub-genre of sci-fi scripts that might be called the long trip spec. Most of them go a little something like this: The characters are on a ship that’s on a long mission in space. An inciting incident occurs; it’s either an accident (usually something to do with an asteroid), or the ship happens upon an anomaly (usually leading to an alien). In a large percentage of these scripts, one of the characters goes insane and gives everyone a hard time. That character is almost always either the captain, or an android/robot.”

You may read Kuciak’s full review here:

https://blog.finaldraft.com/writer-director-pellan-kagerman-on-aniara

Due to my explorations with Aniara, I was inspired to arrive with my own term for this subgenre: Angst Science Fiction, or just Angst SF. Angst is a German word describing a “feeling of dread, anxiety, or anguish.” In terms of Existentialist philosophy, angst is “the dread caused by man’s awareness that his future is not determined but must be freely chosen.” These quotes are taken from The Free Dictionary here: https://www.thefreedictionary.com/angst

To fully realize what I mean by Angst SF, these definitions may be combined with what Kuciak described above, with the further addition of the trope that often the science and technology depicted in such works are secondary to what is happening with the plot. This in turn leaves these story items anywhere from a state of ambiguity to being physically implausible. They are still science fiction, but the science part is largely there to prop up, window dress, and even serve as a decoy or shield for the main themes of the story so that they have a chance to reach a wide audience.

All this is Aniara in a nutshell, and a big reason why I was not terribly motivated to see it at first – or even later, to be honest. Not that such a film must be relentless in its scientific accurate to win me over, but more than once the cinema has given us Angst SF which could easily be a story set on contemporary Earth with baseline humanity. In other words, a typical terrestrial drama.

These are the kinds of film which receive praise from the cinematic literati precisely because they do not focus on the science in their fiction – as if plausible, accurate science were some kind of blemish and therefore unworthy of being ranked among the so-called great works of cinema and literature.

This is one reason why the works of French author Jules Verne (1828-1905) were often shoved into the children’s section of most libraries and bookstores: They dealt in often meticulous detail with what were then considered science fiction topics such as flights to the Moon and mechanically powered submarines, regardless of their literary worth in every other respect. As insult to injury, publishers often abridged Verne’s books, removing those very technical details on the presumed assumption that their readers had no interest in them.

I blame this attitude in no small way on what British chemist C. P. Snow (1905-1980) described in a lecture he gave in 1959 on The Two Cultures: A socially induced division between the worlds of the arts and humanities and the sciences and technology that has hobbled modern humanity’s knowledge and understanding of the wider and more rounded picture in many fields. The films which suffer from this blight use what they see as the tempting treat of science fiction (and not without reason, which I understand) to get the audience to swallow their deeper and often bitter truths about Life, the Universe, and Everything.

Aniara certainly falls into this category in its poetic, operatic, and cinematic forms, though it must be said, to their credit, that the sugar coating employed is a rather faint ruse and anything but the sticky-sweet kind we have been saturated with since the days of Star Wars and the subsequent Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU).

How often people speak of art and science as though they were two entirely different things, with no interconnection. An artist is emotional, they think, and uses only his intuition; he sees all at once and has no need of reason. A scientist is cold, they think, and uses only his reason; he argues carefully step by step, and needs no imagination. That is all wrong. The true artist is quite rational as well as imaginative and knows what he is doing; if he does not, his art suffers. The true scientist is quite imaginative as well as rational, and sometimes leaps to solutions where reason can follow only slowly; if he does not, his science suffers.

– Isaac Asimov (1920-1992), “Prometheus”, The Roving Mind (1983), Chapter 25.

The Existential Horror, the Existential Horror

In February of 2024, I saw that Aniara was available on my primary digital media streaming device. Having a bit of free time on my hands at that moment, I decided to finally give this product of Sweden a try, via my large and no longer quite as astonishing plasma television screen.

One hour and 46 minutes later, I was done.

I did not want to see this film again, ever. Not because Aniara was either badly made or poorly acted – neither was the case – but because it was a deliberate attempt by the filmmakers to slap me in the face about how poorly modern humanity is treating its home planet, then to knock me down completely by saying if we don’t take care of Earth, we are doomed, and everyone will die after experiencing pointless, empty lives as a form of punishment for our collective neglect and abuse. End of the story, so far as they were concerned.

To top it off, the characters were placed in their permanent peril through a series of incidents that probably would not have happened had the filmmakers been as concerned about scientific and technical plausibility as they were about getting their points through and across.

For one final kick for good measure, these messages were wrapped in an existential crisis that permeated the ship’s occupants and went right through the screen to the audience. In addition to the fact that Aniara had a very limited release in American theaters upon arriving in this country, it is little wonder that the film only made forty thousand dollars during its initial box office run in the United States.

COMMENT: Yes, the 2015 film The Martian had to resort to an implausible reason to strand Ares III astronaut Mark Watney alone on Mars – a dust storm blown by winds far more powerful than what can actually occur on the Red Planet due to its very thin atmosphere – but otherwise the plot managed to blend technically realistic scenarios with drama, humor, and above all, an optimistic attitude and can-do spirit that served to keep Watney alive and eventually return him to Earth. All I am saying here is, you can have your cake and eat it, too – if you are willing to make the effort.

Despite my experiences with and feelings towards Aniara, or perhaps because of them, the film compelled me to see what others had thought about this work. Surely, I could not have been the only one who reacted as I had to this film.

What I discovered initially surprised me: Many of the more thoughtful reviews I came across were quite positive. Of course, the nihilistic state of life aboard the runaway spaceship was acknowledged and in certain cases caused the reviewer to respond as I initially had. However, others had praised Aniara for rising above the usual science fiction fray and daring to have a story with no standard happy ending, only a large lesson.

Were these reviewers right about Aniara and my feelings were misplaced? Or to be more generous, was I too heavily influenced by my emotional reactions to the melancholy, sometimes shocking, at certain times brutal, and the overall hopelessness of what I had seen to truly grasp its more enlightened and enlightening aspects during my first experience with the film?

Certainly, this latter notion can be the case, as I am not one to respond impartially to the plight of others, even fictional characters when I get caught up in a well-crafted story with well-developed characters. At the same time, it bothered me that I was emotionally ensnared by Aniara’s sadness and sense of ultimate failure, feelings which I know the makers of this work had every intention of eliciting from their audience. After all, what film does not try to create a mood for its participants, no matter the genre.

When I began delving into this network of positive reviews and essays on Aniara, comprehending on a deeper level why certain folks liked this film and the epic poem it arose from despite the darkness, my path to enlightenment served several purposes: On a basic level, it felt good to know my initial reactions were not misplaced, that some people were pushed away by the slow, unrelieved suffering they witnessed. Others also had to read Martinson’s poem as well for the full picture of Aniara to find the deeper meanings on top of all the ennui, fear, anxiety, depression, decay, and death.

The filmmakers knew they could not simply present their message as a series of dry facts or soak it in the standard Hollywood treatment, for either method would have slipped out of their viewers’ minds as soon as they left the theater or turned off their home screens.

I now see why they chose this epic poem, for only a shock to our nervous systems would accomplish this goal in a world now swamped in a constant deluge of entertainment and information media with varying levels of quality. As a result of this state of affairs, most of what we receive ends up being filtered out by our brains for one reason or another.

Aniara could not be about another space vessel traveling among the stars with a crew of likeable, even lovable characters having a series of cosmic adventures to be wrapped up with a happy bow at the end of two hours. There are already far too many of those kinds of science fiction plots with such inhabitants. Aniara had to be meant for mature thinking adults, for the contents of its messages could only be appreciated and resolved by such beings.

The assumption was that these presumed adult viewers have already been through much in life on a personal level, along with the possession of a certain degree of education, and at the same time are aware of the way our planet has been treated by human civilization with its potential consequences. They could come to terms with a film containing characters who try desperately to cling to whatever purposes and happiness they can either find or create while trapped in a world that has but one ultimate destination: Oblivion.

I soon found myself becoming fascinated with Aniara and the history behind it all, which goes back to the first half of the Twentieth Century. In my journey with this work, I have had several epiphanies and paths of thought which I will gladly share with you throughout this essay. Among them will be discussions on how Aniara ties in to studying one of our earliest and continually captivating concepts for humanity to directly explore and settle the Milky Way galaxy.

“Science fiction plucks from within us our deepest fears and hopes then shows them to us in rough disguise: the monster and the rocket.”

– British-American poet W. H. Auden (1907-1973)

Warning!

Usually at this juncture in my essays on science fiction cinema, I alert my readers that I will be describing the story of the film in detail, so one should expect major plot spoilers along the way. I also recommend that if one has not seen this particular film before, they should probably watch it first before continuing to read further on.

This time, however, I am compelled to add a very strong warning before you attempt to view Aniara. As you may have surmised by now, this is not one of the typical fare fans tend to seek out and enjoy in this genre. Neither is it a horror film in the mainstream sense of the term.

Aniara does have its share of displayed sex, violence, and dark themes: The film is most definitely not for children or even impressionable, sensitive teens and some adults. However, what may really be concerning and emotionally harmful to any and all viewers are the film’s existential elements.

We watch a spaceship full of people who think they are taking a rather brief cruise to a new and hopefully better home, escaping a world that their society has wrecked beyond repair. Instead, they end up becoming trapped in this vessel due to an incident ironically caused by the wanton and random neglect of their own species.

Once the passengers finally realize their ultimate fates, panic and rising desperation quickly manifest themselves amongst these souls. Their circumstances bring about anxiety, depression, hedonistic behaviors, cults, oppression, violence, murder, and suicide, all of which only increase as it becomes clear they are never going to Mars or ever leaving this ship. One cynical character bluntly calls their permanent home a “sarcophagus… a coffin.”

There are cinematic and intellectual reasons for all this, not the least of which is the makers of Aniara attempted to follow the founding poem as closely as possible, as requested by the author’s family, with some updated touches. Nevertheless, I feel a sense of duty and concern to warn anyone reading this that they and those folks they might consider wanting to tell about this film that Aniara has more than its share of triggering elements which could cause a certain level of emotional harm to someone not quite prepared for what is in store.

I was certainly bothered by this film for a while, until I began my examination of its fuller self and meanings, in ways I am not normally disrupted by most science fiction films. However, as I said before, Aniara is not a typical member of the genre but rather a relatively new and now prominent member of Angst Science Fiction.

The odds are more than good that you will survive the experience – it is fiction, after all, and our world has not yet reached this stage of desperation, if ever it will – and hopefully even become enlightened by it, but I could not ask you in good conscience to just dive in without due awareness of the film’s potentially troubling key traits.

“The best thing for being sad,” replied Merlin, beginning to puff and blow, “is to learn something. That’s the only thing that never fails. You may grow old and trembling in your anatomies, you may lie awake at night listening to the disorder of your veins, you may miss your only love, you may see the world about you devastated by evil lunatics, or know your honour trampled in the sewers of baser minds. There is only one thing for it then — to learn. Learn why the world wags and what wags it. That is the only thing which the mind can never exhaust, never alienate, never be tortured by, never fear or distrust, and never dream of regretting. Learning is the only thing for you. Look what a lot of things there are to learn.”

― T.H. White (1906-1964), The Once and Future King (1958)

Mars and Beyond the Infinite

I am dividing up my in-depth retelling of Aniara into the same kind of title card sectioning as conducted throughout the film. We and the crew of the spaceship may be headed for oblivion, but at least we will have some signposts to know just where we are in time if not always literal space; a small sense of order in a reality that is far more titanic and more ancient than humanity and even its home world.

Here are the card titles of what may also be called the story chapters of Aniara. The film displays them in both Swedish and English. Their meanings will become clearer as we travel through the plot:

- 1:a timmen – Hour 1; Rutinresan – Routine Voyage

- 3:e Veckan – Week 3; Irrfarden – Without a Map

- 3:e året – Year 3; Yurgen – The Yurg

- 4:e året – Year 4; Kulterna – The Cults

- 5:e året – Year 5; Kalkylen – The Calculation

- 6:e året – Year 6; Spjutet – The Spear

- 10:e året – Year 10; Jubiléet – The Jubilee

- 24:e året – Year 24; Sarkofagen – The Sarcophagus

- 5,981,407:e året – Year 5,981,407; Lyra Bild – Lyra Constellation

What Does Aniara Mean? An Initial Interpretation

The meaning of the word Aniara in the context of the film and even the epic poem is not straightforward. Harry Martinson himself said that “the name Aniara doesn’t signify anything. I made it up. I wanted to have a beautiful name.”

With all due respect to Mr. Martinson, I must question the complete validity of his statement. He may indeed have merely wanted a beautiful name for his epic work, but as I have found, it also possesses a number of meanings both real and speculative, not to mention even contradictory. Of course, that may have been the author’s intention, to present a word without explanation and leave it up to the interpretation of the reader and viewer.

My leading interpretation for the name’s meaning is the feminine denominative of the ancient Greek adjective aniaros, which means sorrowful as well as sad and despairing. This makes for a great deal of sense in terms of the plot narrative. It is also an example of Angst Science Fiction, for a vessel is – usually – not given such a negative and downer name.

There are enough potential meanings to Aniara that I have given them their own essay section. My only other note here on the name for now is that, perhaps being an American English speaker, it was a struggle for a while not to automatically use the word Ariana instead.

Speaking of Aniara…

A Mote of Dust Suspended in a Sunbeam

As the creative credits open our film against an utterly black background representing space, a small white dot appears, moving slowly across the upper half of the screen from right to left like a floating speck of dust in sunlight.

This glowing dot is very likely the vessel Aniara: Right from the start, the film puts into perspective just how truly small the ship – and the species that built and occupies it – are in the much grander scheme of things.

The main title appears; the moving dot reaches the upper center of the screen between the letters I and the second A of Aniara.

As more credits roll, the background darkness fades, replaced by a sea of churning water coming into view. This is quickly followed by hurricane winds, then driven flood waters wrecking a community. A building is toppled over. Then huge dark tornadoes rip across the landscape, followed by massive fires consuming an entire forest.

This is the state of our planet Earth in an unnamed future era. It has been ravaged by uncontrolled climate conditions aggravated by human society. Our home world has become increasingly unlivable. Humanity and countless other native species are threatened with extinction.

Our vantage point suddenly switches to low Earth orbit. A cylindrical form floats upward on a very long black cable while a massive hurricane churns far below, bursts of lightning flickering along its edges.

As the cylinder comes closer to our vantage point, we see it is a large, sectioned space lift – also known as a space elevator – a collection of passenger and cargo “cars” connected and stacked atop one another in a wheel-shaped pattern. The space lift is moving along the cable towards what appears to be a huge rectangular platform floating above it. This platform is a rather dark shape except for a smattering of external lights and windows glowing from its interior.

We are abruptly brought inside one representative car of the space lift, where we find a group of people who we will learn are basically the latest refugees escaping from their ruined world to start new and hopefully better lives in another one.

The camera moves around this gathered sampling of humanity: A young girl praying. An older woman with burn scars on her face. A mother talking to her fussy child.

A different young woman with red hair and wearing a black blouse is sleeping, her head leaning up against a small rectangular window with stars showing beyond its protective glass. This is our main character, who goes only by Mimarobe or MR. Her real name is never given, only her job title. MR will be our focal point, our Everyperson, if you will.

COMMENT: I wondered why MR’s real name was never mentioned and that neither she nor anyone else had any outward issue with this. In the poem Canto 34, the author Martinson has this explanation, which involves the positions of those who work on the Aniara:

Myself, I have no name. I am of Mima / and so am called no more than mimarobe. / The oath I swore is called the goldondeva. / The name I’d borne was cancelled at “last rounds” and had to be forgotten ever after.

MR awakens to the parent-child commotion, looks about the car, then stares out her small window.

“Want to wave goodbye to Earth?” the mother asks her child. The response is a simple “no.”

“You’ll regret it if you don’t,” the mother counters. “Want to say bye-bye to Earth?”

“Bye-bye, Earth. Bye-bye…”

MR looks up through her private window. Our view follows her gaze, which changes to the lift approaching a large rectangular platform studded with white and yellow lights on its bottom.

As the lift slows next to this platform, a Public Address (PA) announcement cuts through the quiet chatter of the passengers.

“We will now begin docking with Aniara,” the PA address begins. “Please remain with your belts fastened until the gangway is ready and the seat-belt sign is switched off. Please note that checked containers will not be available during the voyage.

“We hope you’ve had a pleasant ascent and wish you a happy, new life on Mars.”

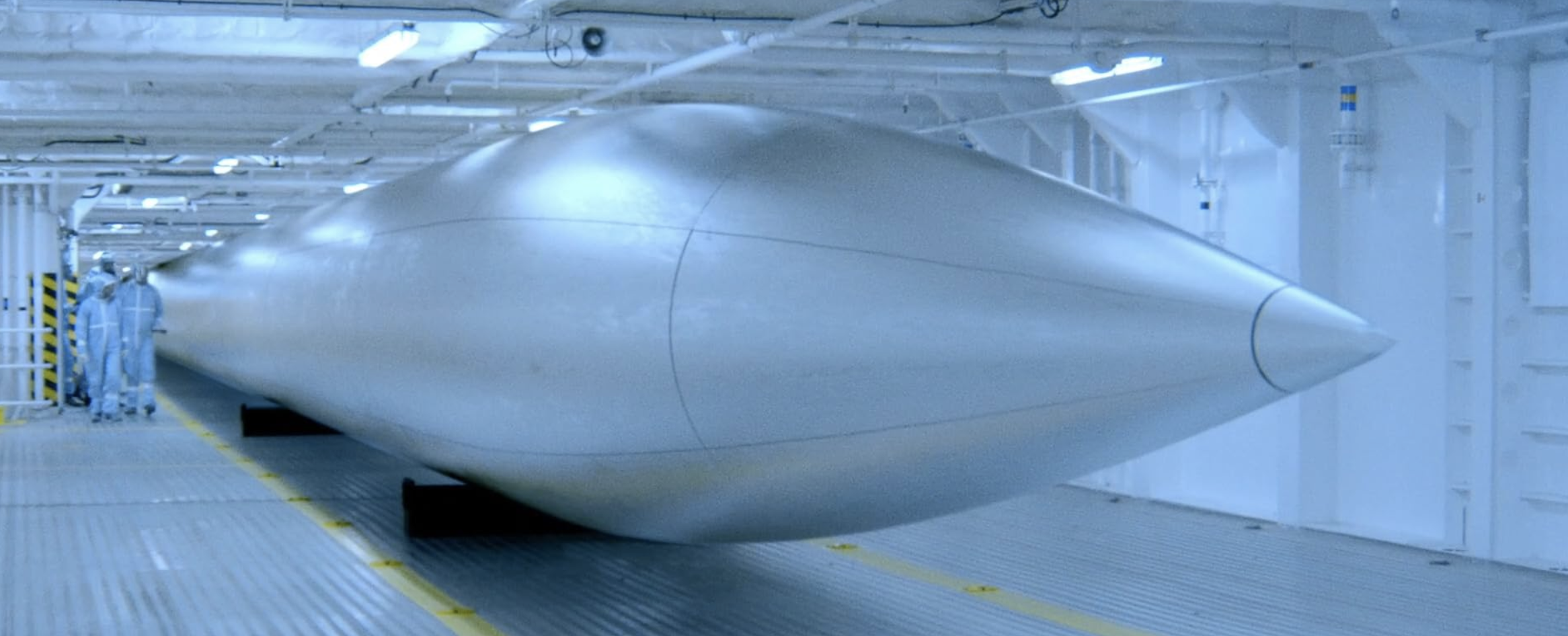

This platform is in fact the spaceship Aniara, a massive vessel that is a literal city in space. One critique of the film refers to the ship’s appearance as “a nightmarish integrated circuit.” Aniara does not resemble the current and past real crewed rocketships we are accustomed to, or the silvery needle-like vessels as imagined in the pre-Space Age days. Its size may be impressive, but Aniara is otherwise a purely utilitarian vehicle, meant only for hauling masses of people and cargo from Earth to Mars and back. Aniara is no vessel of exploration.

COMMENT: While no specific ship dimensions are given outright in the film, the producers did follow the parameters given in Martinson’s poem Canto 8: The Aniara is said to be sixteen thousand feet (4.8 kilometers or 3.03 miles) long and a width of three thousand feet, or 914 meters. The poem also declares the ship carries…

…in its vaults eight thousand souls,

that it was built for large-scale emigration,

that this is only one ship out of thousands

which all, of like dimensions, like design,

ply the placid routes to Mars and Venus…

In the film version, the Aniara is only traveling to the planet Mars. No mention is made of any other similar vessels moving people to Mars, Venus, or anywhere else in the Sol system or beyond.

When Martinson created his work, to many astronomers the planet Venus was still a large question mark in terms of how habitable it was due to that world’s thick, obscuring clouds which envelop the entire alien globe. Nevertheless, the poet chose to go with the “swampy” and “marshy” concept of Venus, which was obviously friendlier to terrestrial life than the roasting desert theory. The hot, dry desert concept of Venus was later proven to be the correct one from the findings returned by the first automated probes to explore the planet in the 1960s.

While Mars was better known to planetary science than Venus in the 1950s and was seriously considered a place harboring hardy plant life and perhaps some simple and equally sturdy animals, there was little illusion by then that the Red Planet was another Earth. Martinson often referred to Mars as a “tundra-cold” world.

The other item of note is that while this future humanity of the film is running away from an environmentally mismanaged Earth, the poem has our species fleeing from a planet wrecked by over thirty nuclear wars! Eventually one final nuclear attack turns our world into a completely lifeless ball of radioactive debris.

The space lift stops at Aniara’s side. Multiple gangway tunnels simultaneously emerge from the spaceship to connect to the levels of circular transport cars for the passengers to disembark upon.

COMMENT: Here is the video clip of the space lift approaching and docking with the Aniara:

MR immediately gets up from her seat, moving over other still sitting passengers as she informs them that she works here as a way of explanation for her rushed behavior.

As MR leaves the space lift and walks onto the Aniara, she encounters two crew personnel greeting her – along with someone inside a tall, anthropomorphic duck costume, complete with a pink vest and oversized yellow bow tie. Undoubtedly this faux bird is meant to entertain, distract, and bring a level of comfort to the arriving refugee children – and perhaps even some of the boarding teenagers and adults.

Having likely encountered them multiple times before in her job, MR pretty much ignores this welcoming committee and heads down an escalator towards a nearby elevator. Even with this initial glance of Aniara’s interior, one already gets the feel of being inside a huge terrestrial shopping mall rather than an interplanetary space vessel.

COMMENT: The filmmakers utilized actual Swedish and Danish malls, ferries, and hotels for their sets, in part to save on their limited filming budget. For the real locations and details on this form of “movie magic”, see the section Further References and Resources (with Titled Subsections), in particular the subsection Concepts of Aniara Blog: Behind-the-Scenes and Production Designs, at the end of this essay.

Upon entering the elevator, MR encounters two ship crew officers. One of them is a rather severe looking woman holding a cup of coffee. Her name is Isagel, one of the Aniara’s pilots. MR seems uncomfortable around her. While not unfriendly to MR, Isagel’s reactions to her appear mild, almost indifferent. She acknowledges the presence of MR, but not in an overly expressive way.

COMMENT: In the 1999 English translation of the poem by Stephen Klass and Leif Sjöberg, they claim that “the name [Isagel] suggests Isis, the Egyptian goddess associated with the cosmic order.” This could be so; after all, she is part of the crew maintaining order aboard the Aniara, and a pilot navigating the ship through space to another world, to be specific.

To me, at first glance, Isagel sounds like Isabel, a form of the name Elizabeth. Isabel comes from the Spanish and Hebrew language meaning either “pledged to God” or “devoted to God”. Why Martinson himself gave this character that name I cannot find.

While in the elevator, we notice that even in this future, the music played in this confined space is still stereotypically bland and unremarkable, perhaps so not to incidentally disturb its passengers in some way.

When the camera aims on the elevator level indicator, we see names and icons for various sections of the ship. They include the Nova Foodcourt, Ceci shopping, a bar, a bowling alley, Hytt (Hyatt?) room numbers 2801 – 2899, and between them a Stardeck with a symbol of a refractor telescope next to the label.

This panel indicates when the elevator stops at the Forebody level. Note: A gym and spa are listed just above Forebody. This is where MR is getting off.

Our scene shifts abruptly from the confines of the elevator to a wide exterior shot of the entire spaceship from overhead, the European continent looming far below. Unlike our views of planet Earth from near space with its vivid blues and whites, the landscape of Eurasia is largely brown in color, with little green to be seen.

Even what we can observe of the surrounding Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea are far darker brown than the currently familiar blue waters. A hurricane swirls off the coast of the United Kingdom. One gets the feeling that such drastic and once primarily tropical zone weather is no longer uncommon for Europe.

The “nightmarish integrated circuit” that is the Aniara hovers over the Eurasian continent made desolate by humanity as a massive hurricane menaces Europe from the northwest.

We move in from the distant view of the black rectangular slab that is Aniara to sail just over its hull towards several levels of the ship illuminating their windows. Presumably we are approaching the aforementioned Forebody section.

MR jogs up to a door along a wood paneled wall. Above her and the door are a singular row of identical electronic viewscreens displaying pleasant images of nature. In the middle of each screen in large white stylized block letters is the word MIMA. The word keeps folding over itself.

MR enters a code into a small black keypad just above the thick wooden door handle. An expected metallic click replies to the proper code: MR pulls the door open and rushes inside. We are given another glimpse of the word MIMA flipping again on two representative screens, in case one missed where we are the first time.

Inside a large and tall white paneled room devoid of any furniture or wall fixtures, MR drops her tan luggage bag at the foot of some long narrow stairs and runs up its steps.

At the top of the stairs, MR presses a button. The wide ceiling transforms from a soft sky-blue palette into a bright sea of churning orange and yellow abstract patterns. An electronic sound emanates from above, resembling gentle ocean waves.

MR sits in a chair overlooking this large and seemingly empty room. Tired emotionally and physically, RM lays her head down on the balcony edge and breaths heavily.

The screen becomes filled with crystal clear water flowing over some rocks. We find MR no longer aboard an artificial ship in black space but instead walking along the bank of a beautiful stream. There is lush green foliage all around her. Moss covers several large boulders nearby. A horizontal tree log adds to her scenery. In the background there are two active waterfalls.

The Mimarobe is immersed in her memory of a beautiful place on Earth which may no longer exist, courtesy of the shipboard Artilect called the Mima.

MR steps around carefully, appreciatively. She does not seem tired or stressed now.

MR approaches a wild raspberry bush. She plucks one of the small red fruits from the plant and puts it in her mouth. She sees a second berry and does the same, looking it over in her fingers before inserting the berry. MR chews the raspberry thoughtfully, then turns to look at the waterfalls.

We and MR are brought back into the MIMA room. MR lifts her head up from the countertop, appearing tired again. Overhead the ceiling patterns continue to glow and flow their orange and yellow patterns.

MR and MIMA disappear, replaced by the Aniara name and logo above it on a white background, as upbeat instrumental music begins to play. The rotating logo depicts an outline drawing of a cube and a triangle superimposed on each other.

This is an introduction video broadcast for the passengers throughout the ship. Our host is the Aniara’s resident Astronomer, Roberta Twelander. Wearing a light blue crew uniform accentuated with a dark blue tie and bearing the Aniara logo on her shoulder, the older woman walks steadily towards the mobile camera filming her.

COMMENT: Although she is only referred to as The Astronomer in the film credits as well as the 1956 epic poem, a woman’s name appears in the lower right corner of this welcoming video, so one must assume this is her actual character’s name. The Astronomer is played by Anneli Martini (born 1948), a veteran Swedish actress who has been in over thirty films since 1977.

The name Twelander does appear once in the poem, in Canto 62, but this moniker belongs to someone who is teaching the ship’s children how to construct a Goldonder, the name Martinson gave to the type of space vessel that Aniara is. This Twelander is described as “calm and cool.”

“Welcome aboard Aniara,” she begins with a smile. “A state-of-the-art transport ship which will take you all the way from Earth to Mars in three weeks.”

As she speaks about this aspect of their ship, a graphic displays, showing a noticeably brown-colored Earth globe to the left of The Astronomer with another smaller sphere representing an orangish Mars to her right. An animated line of red dots arcs over The Astronomer from Earth to the Red Planet: A very simplified version of the intended flight path for the Aniara.

As ship staff are shown preparing a large bar/restaurant for their new guests, The Astronomer continues her verbal walkthrough of the Aniara…

“The air we breathe on the craft is completely natural. It derives from our extensive algae farms. And our 21 restaurants…”

The Astronomer adds to the list of luxuries aboard the ship, which “feature a spa, a tanning salon…. You’ll want for nothing.”

COMMENT: This is the clip from the film where The Astronomer introduces the Aniara’s numerous amenities to its passengers. The video also shares the next scene to be described here.

As The Astronomer continues her spiel, we see passengers being directed by staff to their rooms to settle in.

The vessel’s PA system cuts in, telling the passengers to “please lie down with your seat belts fastened until the gravitational load has adapted to our cruising speed.” A member of the crew is shown securing an older woman to her bed.

“All communication systems will be down until we’ve reached our destination,” the PA adds, without any explanation as to why the Aniara would be completely out of contact with the rest of human civilization during its three-week voyage.

Encountering The Astronomer

MR enters her quarters, surprised to find The Astronomer lying in the bottom bunk, where she is writing in a journal with an ink pen on bound paper.

“So, you’re in my room now?” MR observes to The Astronomer after their saying an opening “Hi” to each other.

“Yes, here I am,” The Astronomer replies. “Served my whole life. Still have to bunk. That’s how they treat astronomers here.”

MR half-humorously comments that she left “people behind on Earth instead so I can have my own closet.”

“I don’t care if they melt into the tarmac,” The Astronomer shoots back.

MR declares that she was only “kidding” in her remark about leaving the home planet, but The Astronomer assures her that she, on the other hand, was not.

“I’ve never been very impressed by people,” adds The Astronomer.

MR replies that she is sorry to hear about The Astronomer’s take on fellow human beings, as she stares at the scientist’s collection of astronomy and physics texts occupying much of their mutual cabin shelves.

COMMENT: Interesting that in this technological future where natural resources are undoubtedly scarce and computers with their electronic storage and internetworking systems should be abundant, that books printed on paper still exist and are actively utilized – at least by The Astronomer. I also note that the titles I could read on the book spines date from the late Twentieth Century. Then again, this might be The Astronomer’s personal preference for reading material both in subject and format, regardless of how most information may otherwise be stored and read in their time.

“You sure seem to enjoy books,” MR observes with an underlying message that her new roommate appears to be dominating their cabin with both her possessions and her presence.

“I took the top shelves,” The Astronomer explains as she stuffs her journal behind her pillow. She then shifts topic gears and asks MR if the woman snores. MR at first says she does not, but then revises her answer with “a little, maybe.”

“Then I’ll have to change cabins on the way back,” responds The Astronomer.

As the two involuntary roommates strap themselves in to their beds, the Aniara’s artificial gravity system begins its load adjustment to adapt to the vessel’s cruising speed. Not secured well enough, The Astronomer’s thin journal floats out from behind her pillow and away from her bed. Unable to grab her private book while being strapped down, Ms. Twelander swears in frustration.

MR can only roll her eyes and quietly shake her head in response to The Astronomer’s outburst. This work shift is going to be a long one, MR is undoubtedly thinking.

1:a timmen (Hour 1) – Rutinresan (Routine Voyage)

The massive bulk of the Aniara heads towards us, the viewers, as she leaves behind an almost unrecognizable Earth as viewed from space. The rumbling ship mimics a big city or industrial park at night.

The Aniara moves away from a dreary-looking Earth towards what both her crew and passengers assume will be a three-week space cruise to the planet Mars, their new home world.

As we watch the Aniara smoothly glide under us, the ship’s captain speaks to the thousands of passengers via the intraship communication system.

“This is your Captain Chefone speaking,” he announces. “We are now cruising at a speed of 64 kilometers per second and are expected to dock with the space lift Valles Marineris in 23 days, 7 hours, and 25 minutes.”

FUN FACTS: 64 kilometers per second (kps) is equivalent to 39.7 miles per second (mps), or almost 143,164 miles per hour (mph). This means the Aniara passed the orbit of the Moon in less than two hours – a distance which took the Apollo missions three days to reach. Valles Marineris is undoubtedly named after the location where the receiving space lift hovers over Mars, one of the largest known canyon systems in the Sol system. Revealed by the American space probe Mariner 9 in 1972, Valles Marineris would stretch across the continental United States if placed there on Earth.

We move back into the Aniara, where a store is shown displaying various pressure suits meant for living and working on the Red Planet. Behind these outfits is a large mural of a Mars settlement containing bland gray domed structures strewn across a rocky reddish landscape. A woman with shoulder-length dark hair named Libidel reluctantly buys one of the pressure suits, which she critiques as “not exactly designer stuff” and asks the store clerk to wrap it up for her.

There is a quick scene of kids playing in an entertainment center. I note this because there are some rather young children bowling with those large and heavy ten-pin bowling balls. One of the little boys, grabbing a rolling lemon-yellow sphere returning to the ball rack, gets his hand pinched by the moving ball and he starts crying in pain.

I am of the impression this was not something staged but rather a real and unfortunate accident during filming. Was this presumably unplanned event left in the film as a symbol and prelude of the emotional and physical pain the passengers and crew will be enduring for the rest of their lives aboard the Aniara?

We are brought back to the entrance of the Mima room. MR is standing near the door with a small group of passengers attending her. MR tries to get more folks strolling by to join them in the Mima Hall, but the ones she addresses politely decline her invitation.

Realizing how fruitless it will be to acquire more visitors at this point, MR introduces herself and her job “as a Mimarobe here on Aniara.”

MR starts to give a “quick back story” about Mima, which “was originally created for the first settlers on Mars…” before two teenage girls in her group visibly lose interest in her budding little history lesson and walk off.

MR recovers from this snub and its clear nonverbal message, reducing her introduction to the Mima to just one sentence:

“Simply put, she transports us back to Earth as it once was.”

MR invites everyone inside, holding open the entrance door for the group as they stroll inside. This task completed, MR closes the heavy wooden door behind her.

We are transported outside Aniara again, this time at some distance from the vessel, where a loose cloud of metal debris drifts through space past us. Among these discarded pieces are a metal screw and a small cylinder with an unknown function. One may assume we are not being shown these random pieces tumbling through the void for nothing.

COMMENT: This is what we would call space junk: Leftover parts from previous space missions, set in their courses through either accidents or other careless actions of those working in the Sol system.

For decades now, Earth has had many thousands of such artificial objects circling our planet, threatening to damage or even destroy whoever and whatever may be operating up there: Anything that can stay in orbit has to be moving at a velocity of at least eighteen thousand miles per hour, or almost twenty-nine thousand kilometer per hour. At this speed, even impacts from paint flecks can be disastrous.

A future society with a permanent presence in the Sol system would undoubtedly generate even more space refuse due to an increase in vehicle traffic and various industrial projects. With MR’s society focused on trying to leave a dying and dangerous Earth, cleaning up the Final Frontier is probably not high on their lists of important duties to perform.

MR walks into the Mima room leading her small gathering. The crowd stares up at Mima glowing a bright orange and yellow on the ceiling above.

MR asks one woman with reddish facial scars to help her demonstrate how to access Mima. The Mimarobe produces a small yellow device resembling a cell phone designed to scan a person’s thoughts. MR asks the woman for her permission to look at what is in her mind and holds the device just behind her head.

We are shown a placid pond filled with green reed water plants just below the surface. Black-winged dragonflies with reflective blue bodies flit about in this vision, with one such insect landing on a singular thin reed just above the water.

MR turns off her little device and puts it away, then tells the woman to look up.

“What you see is personal to you,” MR explains to her charges. “Since Mima has access to your memory banks.”

COMMENT: A hand-held device that pulls memories directly from a person’s mind and displays them for anyone to see? Sidestepping the technical question of how this rather small machine can separate memories from other thoughts in a human brain, the potential for the invasion and violation of a person’s privacy and other abuses should be alarming. The film never pursues these intriguing avenues, however.

The Mimarobe begins to describe how to use the Mima when suddenly there is a violent jolt and the floor tilts. The entire crowd is flung downwards, sliding involuntarily across the floor.

We Lay with Nose-cone Pointed at the Lyre

From space we see the Aniara turning at a sharp angle towards us. Sunlight glints off its black hull as the sound of some power mechanism losing its energy reaches our ears.

On the ship’s bridge, the crew is attempting to deal with an emergency situation. The officers work to stabilize the Aniara while all around them warning sirens blare and the status indicator for the Saba nuclear reactor which powers their massive vessel blinks red in distress. An officer reports that they have “got protruding sections by the Saba reactor,” likely revealing that something has struck this critical area and damaged it.

Captain Chefone orders an officer named Hondo to “initiate course return,” which the officer does not respond to until Chefone calls his name again, sharply this time.

COMMENT: In the 1956 poem, specifically Canto 3, the Aniara must avoid an asteroid (a more accurate term would be planetoid) called Hondo (which the poet says the ship has discovered at the same instant) and subsequently encounters “great swarms of leonids,” which apparently strike the vessel and “led to [the] breakdown of the Saba Unit.” However, from this canto quoted below, the Aniara may well have been struck by a different “ring of rocks.” In any event, it is apparent that the incident itself and not the source of dislocation is what matters more.

Hondo is one of the names for the main island of Japan where Hiroshima sits – the first city to be destroyed by an atomic bomb designed to end that nation’s involvement in World War 2. The Leonids are one of the more prominent meteor showers, so named because the meteors appear to radiate from the northern hemisphere constellation of Leo the Lion as Earth moves through the trail of debris left by Comet Tempel–Tuttle as it circles Sol. The Leonids are famous for having a huge outburst of meteors every 33 years.

Here is all of Canto 3. Compare it to what the 2018 film did and did not borrow from the poem. Also note how certain celestial designations made it into the film, yet with no further clarity than in Martinson’s work.

A swerve to clear the Hondo asteroid

(herewith proclaimed discovered) took us off our course.

We came too wide of Mars, slipped from its orbit

and, to avoid the field of Jupiter,

we settled on the curve of I.C.E.-twelve

within the Magdalena Field’s external ring;

but, meeting with great swarms of leonids,

we headed farther off to Yko-nine.

In the Field of Sari-sixteen we gave up attempts

to turn around.

As we held our curve, a ring of rocks

echographically gave back a torus-image

whose empty center we sought eagerly.

We found it too, but at such dizzying angles

that the passage to it led to breakdown

of the Saba Unit, which was hit hard by space-stones

and great swarms of space-pebbles.

When the ring had moved off and space had cleared,

turning back was possible no longer.

We lay with nose-cone pointed at the Lyre

nor could any change in course be thought of.

We lay in dead space, but to our good fortune

the gravitation-works were still in service,

and heating elements as well as lighting

were not disabled.

Of other apparatus some was damaged

and other parts less damaged could be mended.

Our ill-fate now is irretrievable.

But the mima will hold (we hope) until the end.

The camera focuses on a bridge screen indicating the Aniara’s flight path through space as a wavy white line moving along a blue gridded background. The ship is represented as a yellow triangle slowly drifting off its planned direction towards three concentric circles in the lower right corner of the screen labeled Kupier [Kuiper] Belt, the region of deep space containing countless ancient icy bodies ranging from the solar orbit of Neptune to far beyond.

COMMENT 1 of 2: In the lower left corner of this bridge screen is a single circle labeled Origin [Tellus]. This is Earth, of course. What I find interesting is that the filmmakers called our home planet by its ancient Latin name, Tellus. This name comes from Tellus Mater, the ancient Roman Earth mother goddess.

Initially, I thought that Tellus was also the Swedish name for Earth. However, it turns out their word for the third planet from Sol is Jorden.

COMMENT 2 of 2: Of all the potential places in our planetary system to display, why would this navigation screen show the Kuiper Belt? That region of space is way beyond where the Aniara is headed. Even the Main Planetoid Belt between the solar orbits of Mars and Jupiter would be too far for this vessel’s intended destination.

Was this a form of foreshadowing by the filmmakers? Has this future humanity made it that far out from Earth? If so, do other vessels service those distant settlements? Such questions are left unanswered.

We return to the Mima Hall. A woman asks the Mimarobe what is going on. MR attempts to distract the group by having them continue with the process for using Mima. She has the men and women lie with their stomachs aimed down on floor, then placing their faces into small white circular pillows with breathing holes spaced along their sides. MR tells her group they can lie there for as long as they want.

Once everyone is entranced by their memories generated from the Mima, MR gets up and runs out of the hall into the adjacent concourse.

Here MR encounters the wider chaos created by whatever caused the Aniara to abruptly shift: A baby is screaming in panic. Some people are being helped off the floor, while others are already up but staggering about.

“What happened?” MR asks a colleague near her.

“No idea,” is his only response.

Then the power goes out. The concourse becomes dark except for emergency lights. MR and her coworker look about in concern.

On the bridge, we hear an officer say that the nuclear fuel has been ejected away from the ship into space!

COMMENT: The Aniara crew just added more artificial space debris to the local Cosmos, and this time it is heavily irradiated refuse to boot! And they thought a single screw was a problem! I know space is vast and chock full of natural cosmic radiation, but other than what its loss will mean for the Aniara, the free roaming nuclear fuel will not be considered again in any other respect.

Captain Chefone asks for the “status on the backup system,” and he is told that the “techs are working on it.” Chefone then asks Isagel what their present course is.

“Field SARI-16, angle YKO-9. Lyra constellation ahead,” replies the pilot.

Back on the concourse, MR’s colleague is asking the nearby passengers to “just keep still! Everything is under control.” He repeats his command. MR peers about anxiously.

The main lights snap back on. The coworker looks at MR to inform her that “all is in order,” then just walks away.

MR stays long enough to assist a few passengers around her, including one man who is messily covered in food.

We’ve Had an Incident

A short time later, a large display screen shows a serious-looking Captain Chefone with his arms folded and the following message next to his visage:

IMPORTANT INFORMATION FROM CAPTAIN CHEFONE

A ship-wide announcement comes over the intercom system:

“We will soon be going live with Captain Chefone from the Light Year Hall,” it begins. “The broadcast will also be delivered across all audiovisual devices.”

People begin pouring into the spacious Light Year Hall auditorium. Others find places throughout the ship’s concourse to settle in before other viewing screens.

Chefone is standing behind the main stage of the auditorium. He seems clearly uncomfortable to address the entire ship with the news he has. Chefone does a sound check on the small microphone attached to his uniform by tapping it several times.

The Captain and a tall bald man called by his job title, The Intendent, walk out onto the stage.

“Good evening, dear passengers,” Chefone says. “We’ve had an incident, and I understand your concern. Let me get straight to it. Something highly unlikely has occurred.”

As Chefone is speaking, MR enters the Light Year Hall and stands in the back, listening along with everyone else.

“We had to make an emergency maneuver to avoid a collision with space debris,” explains Chefone, assisted by a computer graphic on the large screen behind him showing the Aniara veering away from its original course to Mars.

“It saved our lives. But our reactor took a hit, as a screw penetrated the hull.”

As Chefone speaks, a new graphic appears showing an interior diagram of the ship’s propulsion section. A rather basic yellow graphic depicting an explosion covers a portion of the diagram where the impact took place.

“The power station caught fire and we had no choice but to eject all our fuel.”

Chefone and the cinematic background music become more somber.

“This unfortunately means we can no longer steer Aniara. We’ve been knocked off-course and cannot turn back.”

His audience looks at each other in mounting concern.

“But… you can remain calm,” Chefone offers. “Once we pass a celestial body, we’ll use its gravity to get back on course.”

A new graphic appears on the screen behind the Captain. This one displays a nondescript spherical object with a small moon nearby that a smaller rectangle representing the Aniara uses to fling itself about and change its direction.

“I can’t tell you exactly when this will happen,” Chefone continues. But you should prepare for the fact that it could be a couple… Definitely no more than two years.”

This time the passengers gasp in shock. Many hands go to many mouths. Some people begin to cry.

The woman we saw earlier purchasing that pressure suit for Mars, Libidel, speaks up.

“Hey. Excuse me? It was supposed to take three weeks.”

One of the crewmen in the audience hall approaches her.

“I’m afraid things have changed,” he responds. “Listen to the Captain now.”

“That’s not possible,” Libidel fires back. “I told my son I’d be there for his fourth birthday!”

“You will of course be duly compensated upon arrival,” the Captain continues. “But for now, we need to cooperate and be there for one another.”

“Remember we have much to be grateful for,” Chefone tells his passengers. “No one was hurt, and our voyage is still ahead of us. In that sense, we’ve been lucky.”

The man finishes his speech with a brave smile.

Our view changes to the glowing orange yellow flows of the Mima. This calming visage is shattered by the screams from Libidel, who is being escorted into the Mima Hall by MR and Chebeba, the scarred woman we met earlier who helped MR demonstrate the Mima.

Kneeling on the Mima Hall floor, MR instructs Libidel to “just let the images come to you” as she looks up at the ceiling, already becoming mesmerized.

Just as the Mimarobe has the distressed mother calmed and focused, Chebeba is also taken with what she is seeing from the Mima and falls to the floor. MR rushes to a corner of the room to retrieve one of the circular pillows and places Chebeba’s face into it.

COMMENT: I learned that these unusual head rests are Thai massage pillows. It makes sense to have these particular pillows, as the clients of the Mima need to lay face down on the floor and their design allows the attending passengers space to breathe in comfort.

Above them all, the Mima churns like a watery lava pool. MR stares up at Mima, seeming to be reveling in her own pleasant memories.

The film brings us next to the impressive stone Reception desk of the Aniara, where a lone staff member is being besieged by lines of passengers who are demanding answers from the poor woman.

“I’ll let you know as soon as I have more information,” she offers, surrounded by frustrated and frantic people. “In the meantime, help yourself to a night snack from the management. Have some snacks, courtesy of the Captain.”

Some of the passengers are subsequently seen walking away while munching on long submarine sandwiches, momentarily placated.

We are cinematically transported to a small and very early Twenty-First Century-looking conference room where various ship department officers are meeting with Captain Chefone to report on the situations of their respective stations.

“How soon can we increase algae production to cover our food needs?” Chefone asks the officer to his immediate right at the discussion table.

“Immediately,” the man replies. “It won’t burden the oxygen system.”

Chefone then inquires of the Restaurant Manager, an older gentleman wearing a green sweater and sporting a rather large mustache, how long the restaurants will last.

“It depends, but in two months we’ll start noticing a difference.”

“Including the algae?” Chefone adds.

“We can survive on it. But it’s not exactly tasty.”

Viewing from a Distance

In another part of the vast spaceship, we find MR laying in her bed under her purple covers and feeling quite restless. Her cabin mate is in a similar pose in the bunk bed below her.

“How are you?” asks The Astronomer to MR.

“Good.”

“Nice repression,” observes The Astronomer.

“I don’t really have anyone waiting for me…” MR expands on her initial answer to the other woman.

“No family?”

“No. None still living.”

“You’ve got Mima,” notes The Astronomer.

MR asks The Astronomer if anyone is waiting for her.

“I’m separated,” the older woman replies. “After 31 years, in total.”

MR makes an exclamation of surprise at this news, then apologizes for her reaction.

“I’m sorry! It just sounds so… long.”

“Of course, 31 years is a long time in a human life span,” The Astronomer opines.

“How come it ended?”

“I don’t know,” is The Astronomer’s answer. “It’s so hard to tell when you’re involved…. You usually need to view it from a distance. Guess I’ll be able to do that now. So, check back with me in a few years’ time.”

Both women smile at The Astronomer’s little inside joke.

3:e Veckan (Week 3) – Irrfarden (Without a Map)

In the third week of the Aniara’s new voyage – when her eight thousand passengers should have arrived at Mars by now – some passengers are still entertaining themselves in the ship’s arcade to occupy their time and distract themselves, including an older woman riding on a virtual motorcycle game.

In this entertainment center, a man walks up to the occupant of the duck suit to ask him where the Mima Hall is.

His inquiry takes us to that very place, where we find MR surrounded by a ring of people. All are bathed in the yellow glow of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) high above them.

“Once you’re inside the images, you won’t feel your body,” MR explains about the Mima, which answers to us why Chebeba just fell to the floor earlier. “That’s why you need to lie on one of these.” She gestures with one of the special pillows in her right hand, waving it about. “Then you can spend hours in here.”

Another group of passengers suddenly appear in the Mima Hall doorway.

“Hey! You can’t come in here!” MR shouts at these intruders. The Mimarobe apologies to her legitimate group for this interruption and runs up to the people crowding at the door.

“No shoes in here!” demands MR. “You need to take the introduction first.”

MR pushes the uninvited passengers out of the room until they have taken the proper steps to enter the Mima Hall. MR then runs back to the group circle and starts helping people put their faces into their pillows.

Later on, we find MR standing at an empty information desk. MR looks around for anyone in charge of this station. On an upper level, MR sees Isagel and a male officer walking by behind a long glass partition; they do not notice MR below.

The bald officer known as The Intendent suddenly appears. MR quickly intercepts his walking path.

“I need to speak to the Captain,” MR requests of the tall officer.

“He’s busy,” The Intendent responds, clearly distracted. “What’s it about?”

“This past week I’ve had more visitors than I usually get for an entire trip,” MR explains. “I need help.”

“I’ll pass it on,” he replies.

“They need training too.”

“I’ll write that down,” The Intendent answers and he begins writing something on a paper attached to a clipboard.

MR tries to ask The Intendent how long it will be before the ship can be turned around, but before she can finish her question, the officer has already moved along out of our sight.

MR stares after the man before she herself walks away, disappointed.

That evening, MR goes for a swim in the Aniara’s spacious swimming pool. She is unexpectedly joined by Isagel, who is wearing a black one-piece swimsuit like hers. MR surreptitiously watches the pilot swimming underwater.

Isagel catches the Mimarobe observing her and suddenly stands up in her pool lane. She gives MR a brief smile as if to say she doesn’t mind before going back to swimming. MR swims off on her own path, noticeably happy at Isagel’s attention to her, mild as it appears on the surface.

Nowhere to Turn

We are taken to one of our first views of the Aniara now in deep space. It is faintly illuminated by our ever-distancing yellow star, whose own light is barely able to penetrate the ancient blackness around it. The low-rumbling ship appears to be moving at a very slow pace.

In her cabin, MR is in her cramped bathroom, staring at the mirror while brushing her teeth. The Astronomer is in her own bed, writing in her journal.

Finished with her dental hygiene, MR gets into her bed before asking her roommate a question.

“Can I ask you something, as an astronomer?”

“Ask away,” invites The Astronomer.

“Do you have any idea which celestial body we’ll be able to turn at?” referring to Chefone’s earlier declaration that they will use the mass of a natural object in space as a gravity assist to redirect the Aniara back towards the planet Mars.

MR’s query is greeted with silence. Thinking she may have simply not heard the answer, MR asks The Astronomer if she said something.

“I didn’t say anything,” confirms The Astronomer. “Because I’m not… anticipating anything.”

“Okay. I thought you knew about that stuff.”

“I do know about that stuff. The answer is ‘none’.”

MR repeats The Astronomer’s last word and when the woman reiterates it, MR sits up in bed in disbelief before moving over the edge of her bed to look at The Astronomer beneath.

“There’s no celestial body to turn at,” confirms The Astronomer yet again.

“You’re kidding?” says MR, in shock.

“GM-54 is the closest we’ll get to. But we’ll never reach its mass. The pilots must have figured that out too.” The Astronomer adds that she does not “get what they’re doing on the captain’s bridge.”

MR lays back down in bed, concerned and thinking.

Without much else to say on the matter, The Astronomer asks MR to turn off the cabin lights so she can sleep.

Their room goes dark. In but a brief moment of time, MR hears The Astronomer start to snore.

COMMENT: Regarding The Astronomer mentioning a celestial object designated GM-54, there is a real worldlet with that name, 2014 GM54. It is a Trans-Neptunian Object (TNO) about the size of the American state of Connecticut, orbiting Sol in almost the same time period as Pluto, once every 248 years. It would be a long reach, but this might be one explanation for the presence of the Kuiper Belt icon on the ship’s navigation screen.

However, according to this entry in Wikipedia, they claim the film is referring to planetoid 54 Alexandra:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/54_Alexandra

Alexandra (minor planet designation: 54 Alexandra) is a carbonaceous asteroid from the intermediate asteroid belt, approximately 155 kilometers [96.31 miles] in diameter. It was discovered by German-French astronomer Hermann Goldschmidt [1802-1866] on 10 September 1858, and named after the German explorer Alexander von Humboldt [1769-1859]; it was the first asteroid to be named after a male.

In Popular Culture

In the Swedish film Aniara (2018) it is mentioned that 54 Alexandra is the closest celestial body which the off-course and out-of-control spacecraft will approach before it leaves the Solar System.

I am not certain where Wikipedia came up with this claim, as they provide no references. I could not find it elsewhere and there is no mention of this planetoid in the 1956 poem. 54 Alexandra might make sense as a slingshot target, for it is much closer than 2014 GM54 in the Kuiper Belt. However, all this speculation seems moot since The Astronomer says the Aniara will not get close enough to any celestial objects to utilize their mass to get back on course to their original destination.

COMMENT: Ironically, Aniara won the “Asteroid” Prize in 2019 for the Best International Film award at that year’s Trieste Science+Fiction Festival.

Unable to sleep at such disturbing news, MR gets out of her bed, dresses quickly, and exits her cabin. She walks down her corridor past a mother holding her baby, who is swaddled in a white blanket. It is apparent that the mother is trying to get her infant to sleep.

We are given a brief perspective of the Aniara exterior again, closer this time. In the background glows the center of the Milky Way galaxy, a huge bulge of billions of suns over 26,000 light years from our Sol system.

MR finds herself in a corridor where there are large windows facing the outside of the ship. She stops and looks at the band of the Milky Way galaxy in the immense distance. Breathing shakily, MR takes a swig from an unlabeled bottle of alcohol she acquired somewhere along her current journey.

As she continues to stare at the stars, MR begins to gasp for breath: She is having a panic attack at the existential realization of what The Astronomer said, exacerbated at what she is witnessing in the void.

MR runs from the indifferent stars all the way to the Mima Hall, still grasping her bottle. The Mimarobe quickly heads upstairs to activate the Mima, which turns from flowing blue to churning orange-yellow-red along the ceiling of the hall.

Running back down to the main hall, MR slips off her shoes, then lays down on the floor in a fetal position, cradling her bottle and still gasping for air.

We see what MR is experiencing through the Mima: A deep, lush, and green temperate zone forest. MR walks barefoot through these calming woods on dry, dead leaves. Nearby birds are chirping. She looks around at the beautiful tree canopy, seeming content.

The film does another one of its dramatic scene shifts: This time we go from a peaceful forest to staring down a large metal vat full of a whitish liquid resembling oatmeal being automatically stirred. A pan out shows kitchen workers in green aprons and darker brimless caps preparing algae for mass consumption.

We May as Well Live Here

Another scene shift: We follow MR moving quickly up a concourse where a crowd of people are gathered around a closed door between stores, guarded by a single officer.

MR proclaims to the crowd that she works here as she cuts through them and pushes open the large green metal door, bringing her into a two-toned access corridor. MR finds an older balding man wearing a horizontally striped shirt under a green sweatshirt sitting on the floor against one wall. He is attended by two ship officers on either side of him: One is The Intendent and the other is a younger man with a dark beard.

“It’s some kind of panic attack or psychosis,” explains one officer to MR about this situation she finds herself in.

“Hi,” says MR to the distraught man. “I work as a Mimarobe. I’d like you to come with me.”

The man on the floor responds to MR in Spanish. The bearded officer translates his words for MR.

“He’s asking if you’re a devil?”

MR merely stares at the translator, who continues his task.

“A woman at the Planetarium told him; she’s an astronomer and she knows…. She says we won’t be able to turn around.”

“No, that’s not true,” MR lies to the man via the translator. “Tell him… Tell him to come with me, I promise he’ll feel better.”

Still panicking, the Spanish man reaches out and grabs MR by her shirt collar, hitting the Mimarobe on the left side of her face. Suddenly realizing what he has just done, the man quickly pulls away his hand and stares at MR in fear.

Clearly not happy with this physical assault, MR looks at the Spanish man and says nothing for a moment. Then she leans in closer to him.

“What do you think life on Mars is?” asks MR without expecting an actual answer from the target of her ire. “Some kind of paradise? It’s not. It’s cold. Nothing grows except for a small frost-proof tulip, this small.”

MR aggressively gestures with her index and thumb at the Spanish man to show him the general puny size of this specialized tulip species – and perhaps the Spanish man and every other human being in comparison to the rest of the Cosmos as well.

COMMENT 1 of 2: Since it is highly unlikely that terrestrial tulips would be found as a native plant on Mars, the alternate answer is that this humanity is trying to terraform the Red Planet to one day make it livable for Earthly flora and fauna. It will probably be a long process that will not bear literal fruit for generations. Emigrating humans will have to remain in artificial environments for now, be it in open space structures or in dwellings on other worlds.

Even more difficult to overcome will be the fact that Mars’ mass is ten times less than Earth’s, making the smaller planet’s gravitational pull only 38 percent that of Earth. The only mass-comparable world in our Sol system would be Venus, but that place has its own special environmental issues which would make conventional settling quite difficult.

COMMENT 2 of 2: It is interesting that tulips were chosen as the flower mentioned by MR in the film. The makers undoubtedly took this directly from the Martinson poem in Canto 40, where the author mentions “black frigitulips grow[ing], tempered to the planetary freeze.”

Were both the poet and the filmmakers trying to inject a symbol of hope into their work? I say this because tulips are symbols of new beginnings and rebirth, which is what the humans settling Mars are trying to do with their lives on that world. As for other relevant comparisons regarding this flower, I quote the following from this page:

https://foliagefriend.com/tulip-flower-meaning/

In spirituality, tulips are considered to symbolize new beginnings and rebirth. The flower’s ability to come back every year, stronger and better than before, is also one reason why it is thought to represent new life. Tulips are also believed to symbolize love, purity, innocence, forgiveness, and trust, making them a popular choice for religious and spiritual ceremonies.

Furthermore, tulips are often associated with enlightenment and spiritual awakening. The flower’s vibrant colors and delicate petals are said to represent the beauty and fragility of life, reminding us to appreciate every moment and live in the present. Tulips are also believed to have a calming effect on the mind and body, making them a popular choice for meditation and relaxation practices.

“Want me to translate?” asks the bearded officer of MR. Frustrated and feeling it would be pointless in any case, MR has only one response for the man.

“Just say we may as well live here.”

Sometime later, we see the Spanish man at a food court getting a meal. He is looking a bit sheepish at his recent panic behavior.

The man seems to be recovering from his bout of hysteria when he looks over at some tall black windows adjacent to the food court. Seeing through them the same stars that MR had earlier, he starts to panic again, yelling loudly in his native language and gesticulating wildly.

Two nearby officers rush in and restrain the Spanish man before escorting him away. The court area crowd stare after him. One has to wonder if they worry when they will become the next existential “victims” of the hot yet cold stars.

The terrified man is brought to the one place on the ship that might calm him down: The Mima. As the two officers stand nearby at the ready, the Mimarobe coaxes the Spanish man to lie down among many other passengers already utilizing the Mima and place his face into a pillow.

That task completed, MR notices the two officers are staring up at the shimmering patterns of the Mima on the ceiling. As happened with Chebeba, the man and woman become transfixed with the memories being released by the AI and collapse onto the floor. This time, MR is able to rouse the pair to get them to leave the Mima Hall and go back to their duties before they inadvertently become her latest clients.