By Larry Klaes

A new book looking at the inner lives of astronauts is Larry Klaes’ subject today. Planning for long-term missions like a manned trip to Mars requires a great deal of work on closed systems, as we’ve recently discussed. But we also have to consider the psychological issues raised by confinement in a cramped environment for long durations, issues that are one thing in the confines of low-Earth orbit but perhaps another when far from the home world.

Early on the morning of February 5, 2007, several officers from the Orlando Police Department in Florida were summoned to the Orlando International Airport, where they arrested a female suspect. This woman was alleged to have attacked another woman she had been stalking while the latter sat in her car in the airport parking lot. Judging by the various items later found in the vehicle the suspect had used as transportation to the Sunshine State all the way from her home in Houston, Texas, her ultimate intent was to kidnap and possibly conduct even worse actions upon her victim.

While such a criminal incident is sadly not uncommon in modern society, what surprised and even shocked the public upon learning what happened was the occupation of the perpetrator: She was a veteran NASA astronaut, a flight engineer named Lisa Nowak who had flown on the Space Shuttle Discovery in July of 2006. As a member of the STS-121 mission, Nowak spent almost two weeks in Earth orbit aboard the International Space Station (ISS), performing among other duties the operation of the winged spacecraft’s robotic arm.

It seems that the woman who Nowak went after, a U.S. Air Force Captain named Colleen Shipman, was in a relationship with a male astronaut named William Oefelein. Nowak had also been romantically involved with Oefelein earlier, but he had gradually broken off their relationship and started a new one with Shipman. Oefelein would later state that he thought Nowak seemed fine about his ending their affair and moving on to another woman. However, by then it was painfully and very publicly obvious that Oefelein had not thoroughly consulted enough with his former companion on this matter.

NASA would eventually dismiss Nowak and Oefelein from their astronaut corps, the first American space explorers ever formally forced to leave the agency. NASA also created an official Code of Conduct for their employees in the wake of this publicity nightmare.

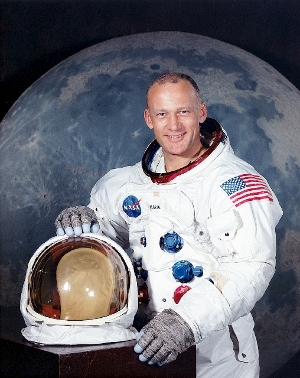

Now I have no documented proof of this, but I strongly suspect that the Nowak incident played a large but officially unacknowledged role in the creation of the recent offering by the NASA History Program Office book titled Psychology of Space Exploration: Contemporary Research in Historical Perspective (NASA SP-2011-4411), edited by Douglas A. Vakoch, a professor in the Department of Clinical Psychology at the California Institute for Integral Studies, as well as the director of Interstellar Message Composition at The SETI Institute.

Quoting from a NASA press release (11-223), which appeared about the same time as the book:

Psychology of Space Exploration is a collection of essays from leading space psychologists. They place their recent research in historical context by looking at changes in space missions and psychosocial science over the past 50 years. What makes up the “right stuff” for astronauts has changed as the early space race gave way to international cooperation.

The book itself is available online in several formats.

From the Right Stuff to All Kinds of Stuff

It may seem obvious to say that astronauts are as human as the rest of us, but in fact our culture has long viewed those who boldly go into the Final Frontier atop a controlled series of explosions otherwise known as a rocket in a much different and higher regard than most mere mortals. Even before the first person donned a silvery spacesuit and stepped inside a cramped and conical Mercury spacecraft mated to a former ICBM for a brief arcing flight over the Atlantic Ocean in 1961, NASA’s first group of human space explorers – known collectively as the Mercury Seven – were being presented from their very first press briefing in 1959 as virtual demigods who had the right skills and mental attitude to brave the unknown perils of the Universe.

Image: The Mercury Seven stand in front of a F-106 Delta Dart. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The Mercury Seven astronauts were not just men: They were an elite breed of space warriors ready to conquer the Cosmos who also represented the best that the United States of America had to offer when it came to their citizens, their technology, and their science. The nation’s first space explorers may have been ultimately human and limited in various ways, even flawed, but the agency’s goal was to keep any issues in check through their missions at the least and preferably during their full tenure with NASA.

By the time of Nowak’s incident, astronauts may not have been the demigods of the days of Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo, but they were still looked upon as highly capable people who ventured to places few others have gone and who did not give into human passions beyond a few moments of wonder at the Universe, realistic or not. This is why Nowak and Oefelein’s behaviors were so shocking to the public even four decades after the first generations of space explorers.

There are two reasons why I brought up the dramatic events of 2007 with Lisa Nowak: The first is my aforementioned hypothesis that what took place between the former astronaut and her perceived romantic rival led to NASA feeling the need to examine their policies regarding the human beings they send into space and formally documenting the resulting studies.

The second reason is that Psychology of Space Exploration needed more of these personal stories about the astronauts and cosmonauts. Now certainly there were some of these throughout the book: The Introduction to Chapter 1 relays a tale about a test pilot who was applying to be an astronaut who told an evaluating psychiatrist about the time the experimental aircraft he was flying started spinning out of control. The pilot responded to this emergency by calmly leafing through the vehicle’s operating manual to solve the immediate problem, which he obviously did.

Nevertheless, more of these kinds of stories would have not only made the book a bit less dry as it was in places, but they would have added immeasurably to the information content of this work.

As just one example, in Chapter 2 on page 26, the author mentions (from another source) that the Soviet space missions “Soyuz 21 (1976), Soyuz T-14 (1985), and Soyuz TM-2 (1987) were shortened because of mood, performance, and interpersonal issues. Brian Harvey wrote that psychological factors contributed to the early evacuation of a Salyut 7 [space station] crew.”

The problem here is that the book then moves on without going into any details about exactly what happened to curtail these missions. Knowing what took place would certainly be useful in making sure that future space ventures, especially the really long duration ones that will be of necessity as we move past our Moon, could be the difference between a secure and functioning crew and a disaster.

Incidentally, the author noted that the Soviets, who were usually reticent about giving out many technical details or goals on most space missions manned and robotic, were more open when it came to the experiences of their cosmonauts and showed more interest in their physiological situations in confined microgravity situations than NASA often did with their astronauts.

The Soviet space program also had a longer period of actual experience with humans living aboard space stations starting in 1971 with Salyut 1 (or Soyuz 9 in 1970 if you want to count that early space endurance record-holding jaunt) which NASA did not share between their three Skylab missions in 1973-1974 until their joint involvement with the Soviet Mir station in the 1990s. Having the details from that era would be of obvious benefit and interest.

Image: The MIR station hovering over Earth. It deorbited in March 21, 2001.The station was serviced by the Soyuz spacecraft, Progress spacecraft and U.S. space shuttles, and was visited by astronauts and cosmonauts from 12 different nations. It endured 15 years in orbit, three times its planned lifetime. Credit: NASA.

Granted, as with a collection of research papers such as this, there are plenty of references. Finding the stories this way is not a problem if you are doing your own research and using Psychology of Space Exploration as a reference source, but for the more casual reader it could be a bit of a disappointment when these items are not readily available.

While I think most people who want to learn more about how our space explorers are affected by and respond to and during their missions into the Final Frontier will find something of interest and value throughout this book, Psychology of Space Exploration is largely a reference work that goes into levels of certain details as befitting literature of its type while missing a number of others which I think are just as important for a comprehensive view of human expansion into space, both in the past, the present, and most vitally the future.

The ultimate goal of putting people into space is eventually to create a permanent presence of our species beyond Earth. That is the grand aim even if their initial underlying purposes were more geared towards engineering and geopolitical goals. This is similar to the history of the early navigators who crossed the Atlantic Ocean from Europe to the New World, for they too had other plans initially in mind, although the ultimate result was the founding of the many nations that exist in the Western Hemisphere today.

To give some examples of what I feel is missing and limited in representation in Psychology of Space Exploration, there is but a brief mention of what author Frank White has labeled the “Overview Effect”. As the book states, this is the result of “truly transformative experiences [from flying in space] including sense of wonder and awe, unity with nature, transcendence, and universal brotherhood.”

Clearly this is a very positive reaction to being in space, one which could have quite helpful benefits for those who are exploring the Universe. The Overview Effect might also have an ironic down side, one where a working astronaut might become so caught up in the “wonder and awe” of the surrounding Cosmos away from Earth that he or she could miss a critical mission operation or even forget what they were originally meant to do. Mercury astronaut Scott Carpenter may have been one of the earliest “victims” of the Overview Effect during his Aurora 7 mission in 1962. Apparently his very human reaction to being immersed in the Final Frontier in part caused Carpenter to miss some key objectives during his mission in Earth orbit and even overshoot his landing zone by some 250 miles. Carpenter never flew in space again, despite being one of the top astronauts among the Mercury Seven. It would seem that in those early days of the Space Race, having the Right Stuff did not include getting caught up with the view outside one’s spacecraft window, at least so overtly.

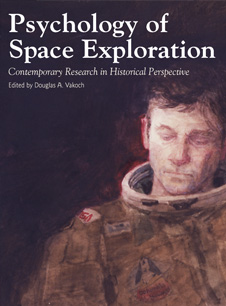

Another item largely missing from Psychology of Space Exploration is the effects on space personnel after they come home from a mission. Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, who with Neil Armstrong became the first two humans to walk on the surface of the Moon with the Apollo 11 mission in 1969, is one of the earliest examples of publicly displaying the truly human side of being an astronaut.

Although not revealed publicly until 2001 by former NASA flight official Christopher C. Kraft, Jr., in his autobiography Flight: My Life in Mission Control, the real reason Aldrin was not selected to be the first one to step out of the Apollo Lunar Module Eagle onto the Moon was due to the space agency’s personal preference for Armstrong, who Kraft called “reticent, soft-spoken, and heroic.” Aldrin, on the other hand, “was overtly opinionated and ambitious, making it clear within NASA why he thought he should be first [to walk on the Moon].”

Image: Astronaut Buzz Aldrin. Credit: NASA.

Even though Aldrin was a fighter pilot during the Korean War, earned a doctorate in astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and played an important role in solving the EVA issues that had plagued most of the Gemini missions and was critical to the success of Apollo and beyond, his lack of following the unspoken code of the Right Stuff kept him from making that historic achievement.

Aldrin would later throw the accepted version of the Right Stuff for astronauts right out the proverbial window when he penned a very candid book titled Return to Earth (Random House, 1973). The first of two autobiographies, the book revealed personal details as had no space explorer before and few since, including the severe depression and alcoholism Aldrin went through after the Apollo 11 mission and his departure from NASA altogether several years later, never to reach the literal heights he accomplished in 1969 or even to fly in space again. Although Aldrin would later recover and become a major advocate of space exploration, he is not even given a mention in Psychology of Space Exploration. In light of what later happened with Nowak and several other astronauts in their post-career lives, I think this is a serious omission from a book that is all about the mental states of space explorers.

The other glaring omission from this work is any discussion of the human reproductive process in space. NASA has been especially squeamish about this particular behavior in the Final Frontier. There is no official report from any space agency with a manned program on the various aspects of reproduction among any of its space explorers, only some rumors and anecdotes of questionable authenticity.

As with so much else regarding the early days of the Space Age, that may not have been an issue with the relatively few (primarily male) astronauts and cosmonauts confined to cramped spacecraft for a matter of days and weeks, but this will certainly change once we have truly long duration missions, space tourism, and non-professionals living permanently off Earth. As with daily life on this planet, there will be situations and issues long before and after the one aspect of human reproduction that is so often focused upon. Unfortunately, outside of some experiments with lower animals, real data on this activity vital to a permanent human presence in the Sol system and beyond is absent.

I recognize that Psychology of Space Exploration is largely a historical perspective on human behavior and interaction in space. As there have been no human births yet in either microgravity conditions or on another world and the other behaviors associated with reproduction are publicly unknown, this work cannot really be faulted for lacking any serious information on the subject. What this does display, however, is how far behind NASA and all other space agencies are in an area which will likely be the determining factor in whether humans expand into the Cosmos or remain confined to Earth.

So Far Along, So Far to Go

What the Psychology of Space Exploration ultimately demonstrates is that despite real and important improvements in how astronauts deal with being in space and the way NASA views and treats them since the days of Project Mercury, we are not fully ready for a manned scientific expedition to Mars, let alone colonizing other worlds.

Staying in low Earth orbit for six months at a stint aboard the ISS as a standard space mission these days gives an incomplete picture of what those who will be spending several years traveling to and from the Red Planet across many millions of miles of space will have to endure and experience. If an emergency arises that requires more than what the mission crew can handle, Earth will likely be a distant blue star for them rather than the friendly globe occupying most of their view which all but the Apollo astronauts have experienced since 1961.

Regarding this view of the shrinking Earth from deep space, the multiple authors of Chapter 4 noted that ISS astronauts took 84.5 percent of the photographs during the mission inspired by their motivation and choices. Most of these images were of our planet moving over 200 miles below their feet. The authors noted how much of an emotional uplift it was for the astronauts to image Earth in their own time and in their own way.

The chapter authors also had this to say about what an expedition to Mars might encounter:

As we begin to plan for interplanetary missions, it is important to consider what types of activities could be substituted. Perhaps the crewmembers best suited to a Mars transit are those individuals who can get a boost to psychological well-being from scientific observations and astronomical imaging. Replacements for the challenge of mastering 800-millimeter photography could also be identified. As humans head beyond low-Earth orbit, crewmembers looking at Earth will only see a pale-blue dot, and then, someday in the far future, they will be too far away to view Earth at all.

Image: Jerrie Cobb poses next to a Mercury spaceship capsule. Although she never flew in space, Cobb, along with twenty-four other women, underwent physical tests similar to those taken by the Mercury astronauts with the belief that she might become an astronaut trainee. All the women who participated in the program, known as First Lady Astronaut Trainees, were skilled pilots. Dr. Randy Lovelace, a NASA scientist who had conducted the official Mercury program physicals, administered the tests at his private clinic without official NASA sanction. Cobb passed all the training exercises, ranking in the top 2% of all astronaut candidates of both genders. Credit: NASA.

Now of course we could prepare and send a crewed spaceship to Mars and back with a fair guarantee of success, both in terms of collecting scientific information on that planet and in the survival of the human explorers, starting today if we so chose to follow that path. The issue, though, is whether we would have a mission of high or low quality (or outright disaster) and if the results of that initial effort of human extension to an alien world would translate into our species moving beyond Earth indefinitely to make the rest of the Cosmos a true home.

The data recorded throughout Psychology of Space Exploration clearly indicate that despite over five decades of direct human expeditions by many hundreds of people, we need much more than just six months to one year at most in a collection of confined spaces repeatedly circling Earth. This will affect not only our journeys and colonization efforts throughout the Sol system but certainly should we go with the concept of a Worldship and its multigenerational crew as a means for our descendants to voyage to other suns and their planets.

This book is an excellent reflection of NASA in its current state and human space exploration in general. As with the agency’s manned space program since the days when the Mercury Seven were first introduced to the world in 1959, we have indeed come a long way in terms of direct space experience, mission durations, gender and ethnic diversity, and understanding and admitting the physiological needs of those men and women who are brave and capable enough to deliberately venture into a realm they and their ancestors did not evolve in and which could destroy them in mere seconds.

Having said all this, what I hope is apparent is that we now need a new book – perhaps one written outside the confines of NASA – which will address in rigorous detail the missing issues I have brought to light in this piece. This request and the subsequent next steps in our species’ expansion into space – which will also eventually take place beyond the organizational borders of NASA – cannot but help to improve our chances of becoming a truly enduring and universal society in a Cosmos where certainty and safety are eventually not guaranteed to beings who remain confined physically and mentally to but one world.

In a scenario where a frozen embryo, artificially gestated, and then raised by android parents, every attempt to give the child the best possible upbringing despite the circumstances might mean that we would like for the child to be “resilient”. There are some kids who succeed in life despite having come from a bad family environment. If there is a genetic basis to resilience, then having the embryos be the genetic clone of a child whose has already demonstrated resilience could give the exochild a better chance at achieving some level of psychological health.

Obviously, the primary challenge would be to ensure that the android parents were as realistically interacting with the exochild as possible. As I have stated previously, I believe that this can be accomplished without necessarily having full AI but rather recorded and played back behavior as well as an expert system much better than Siri. Raising simultaneous siblings would have someone in their life who was entirely real. One would have to figure out how to best make the child aware of their situation, especially the fact that their android parents were largely recordings of their biological parents. There is also the psychological problem of limited social opportunities. Technology to provide virtual interactive friends should be readily available before the close pf this century. The lack of mates could be mitigated by having other simultaneous, separated children of the opposite sex being raised. None of this would be ideal which means that it would only be justified in the context of a program in which artificial gestation would be initiated only if the mission had no evidence that humanity had survived – hence, the Embryo Space Colonization to Avoid Possible Extinction (ESCAPE).

I believe that the psychology of live crews on decades-long journies is irrelevant because the “crew” will either be in hibernating or frozen embryo forms for economic reasons.

You couldn’t have picked a more timely piece than this for September 11th…

As to the success of a worldship….maybe robots would be best to repair and steer the ship…let us hope hibernation eventually works out as a means of coping with the dynamics of the criminal minds inadvertantly chosen as worldship passengers….sorry to be so negative….read ‘Across the Universe’ for insights into murderous multi-generational travel…JDS

While careful selection of astronauts hopefully weeds out the downright dysfunctional or incompetent, it can’t (and probably shouldn’t try) to get rid of human foibles.

One thing I note in the post is the emphasis on the space missions. However most astronauts spend relatively little time in space. They do however spend years immersed in what you might call the astronaut culture. This may have more of an effect on them than actual space travel (at least of the sort we have carried out thus far).

I never liked comparisons between the early navigators like Columbus and space explorers. These comparisons bring up memories of the European’s violence and cruelty toward the native peoples of the lands they had come to, and of how whole races were drive off of their land or even almost wiped out genocidal wars.

Future space travelers shouldn’t- and won’t- behave anything like these early conquistadors. Furthermore, space advocates shouldn’t turn people of native ancestry off of space exploration by presenting it as “Columbus, only in Space!!”. You can make much better analogies comparing early scientific expeditions and space flights, or even fish coming out of the ocean onto land and humans becoming a spacefaring species. Columbus sought only wealth, not scientific knowledge nor any advancement for the human species.

Discussions of human sexuality should not puritanically link sex only to the reproductive process. Let’s be honest, you are being pretty squeamish yourself if you pretend that the only reason humans ever have sex is to conceive children. Sex has always been an important aspect of human culture and relationships, and will remain so in space. Space sex will be an important issue even on a year-long flight during which the astronauts are on contraceptives.

In fact, space reproduction isn’t even that strongly linked to the psychological ramifications of space sex. The question of whether children can be conceived and form properly in space, given the hazards of low gravity and radiation, doesn’t have much immediate bearing on the psychological issues surrounding sexual relationships during space flights. There are several possibilities for a space colony or starship crew when it comes to reproduction, and not all of them will involve sex. For instance, the ship may carry frozen gametes to introduce genetic diversity to a small starship crew and avoid inbreeding.

It is even possible that reproduction will occur without sex and childbirth in the future, perhaps using artificial wombs. By the time we have interstellar flight, it is quite likely that we will have alternatives to normal human reproduction that could come into play during space colonization. A major benefit of such reproductive technology- for women at least- is that they would take the difficulties of pregnancy and childbirth off of the female members of a colonization expedition. A small colony, after all, might require a certain number of children to be born in order for the colony’s population to grow, possibly even requiring women to bear “duty children” for the colony. Such an unpleasant prospect might be avoided by artificial wombs. Then again, perhaps enough humans will be brought to colony that such measures won’t be necessary.

Naturally, NASA has not discussed any of this. To be fair, NASA is not in the business of space colonization or interstellar travel, although the ramifications of sexual relationships between male and female astronauts on extended flights to Mars should be of interest to mission planners. Science fiction is the main arena for investigating the issues surrounding interstellar flight and space colonization today. Notably, Star Trek has been squeamish about reproductive technology- women invariably choose to bear children the normal way, and this in a society where starships, transporters, phasers, and advanced medical technology are commonplace!!

Interesting article with the female point of view on Mercury, astronauts and male psychology from Athena Andreadis here:

http://www.starshipnivan.com/blog/?p=6618

Written recently to commemorate Sally Ride.

Christopher Phoenix said on September 11, 2012 at 18:52:

[LJK] “This is similar to the history of the early navigators who crossed the Atlantic Ocean from Europe to the New World, for they too had other plans initially in mind, although the ultimate result was the founding of the many nations that exist in the Western Hemisphere today.”

“I never liked comparisons between the early navigators like Columbus and space explorers. These comparisons bring up memories of the European’s violence and cruelty toward the native peoples of the lands they had come to, and of how whole races were drive off of their land or even almost wiped out genocidal wars. ”

LJK replies:

There may not be any “natives” to conquer or destroy in the Sol system, but our Space Age did not arise from pure scientific intentions despite what they like to tell us. The era was born and evolved from the rocket weapons of World War 2 and the geopolitical tensions of the superpowers of the Cold War. And these days it looks like corporations will decide if we become permanent residents of space or not.

Science has more often than not been either a backseat rider or a beggar of fallen table scraps from our space efforts. If they relied on pure science, we wouldn’t have nearly the programs we do even today and especially in earlier times. So political correctness qualms aside, I think the analogy is apt.

When we do head out into the stars, if we come across an Earthlike planet that those who advocate interstellar exploration tend to advocate in terms of goals (as in colonization) – since a planet or moon which is similar to our world is likely that way because it has native life forms, what happens with the starship crew that has come all those light years and generations to settle on that alien globe? Will it be peaceful, neutral, or will we see a version of Avatar? This scenario will one day not be science fiction.

And as for reproduction in space, why don’t we find out first if it can even happen the “regular” way before we start introducing artificial wombs, frozen gametes, cloning, and whatever else that is still awaiting feasibility.

And as Star Trek is just science fiction (and rather dated in many ways), I am not terribly concerned as to how they portray such things. It is a television series primarily designed to entertain the contemporary masses and make lots of money in the process.

The late G. Harry Stine wrote about sex aboard the space shuttle by “astro-naughties,” but while intriguing none of these tales have, as far as I know, been confirmed. Since voyages to Mars and transoceanic voyages are of similar duration, the usual psycho-sexual complications will occur. Even if they were all happily married couples, sexual awkwardness will be part of the business. Our ancestors’ ships had all male crews but plenty of distractions (terrifying storms among them) and discipline was very strict. In space, not so much. Minds and hands will wander. I know of at least one pirate ship that had an all-gay crew and a female captain, but that doesn’t appear to be an option here. Indeed, it is something that will have to go into the planning and overall design of mission. A.E. van Vogt in the Voyage of the Space Beagle thought we might have a drug that would eliminate the physical need, though not the mental, for sex. Have my doubts.

In the old days of manned space exploration, an astronaut was terminated if he even got a divorce, no matter how civil or “friendly.” But this was part of the culture of the time. Divorce was a bad career move anywhere. But all that had changed by the 80s. If you got divorced in the 80s or later, everyone simply asked the name of your new girlfriend (h/t to Tom Wolfe). How much looser can things get before we have swingers in space?

I’ve complained myself on applying the european model of exploration to the solar system, but there are things that can still be learned. One just has to be cautious. As for Columbus, he admired the indians and he first encountered cruelty among the Caribs who were bad news to anyone. See Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus. The most telling memoirs of the Spanish conquest of the Americas I have come across is The Relation of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. It’s all terror and tragedy. De Vaca was also an admirer of the Indians. His surviving the doomed expedition he was a part of has to be considered something of a miracle. Finally, there is Terrence Malick’s film, The New World, a re-imaging of the Pocahontas legend, as historically accurate as the director could make it. Think of it as Avatar for adults. Again the theme is the tragedy that results from a clash of completely incompatible world views. White guilt is nowhere to be found.

The point I am trying to make is that tragedy can result from any situation. The indians and europeans were all human beings. And for the foreseeable future, it is human beings of one sort or another whom we will be dealing with. I can’t help but worry.

Recent studies indicate that most of the population loss to native North American peoples occurred prior to extensive colonization, from diseases accidentally introduced by the earliest European settlers and their animals. Epidemics raced outward from the initial contact points, leaving the land almost empty by the time colonists arrived. Here in Hawaii as well there was a 90% drop in the Hawaiian population in the first 100 years after Cook’s arrival, even though there was almost no violence at all between Hawaiians and whites or Asians. Interestingly, in Central and South America where conquest was the open intention of the Spanish and Portuguese, the percentage of native peoples in the population is a lot higher than it is in areas settled by the supposedly more enlightened French and English. It seems that the intentions of new arrivals to a strange ecosystem may not be very relevant. Having sterile spacesuits (or even staying away completely from inhabited worlds) might be the most humane thing we can do.

Does anyone know whether it is feasible to follow a secant trajectory

from Earth back to itself, but crossing say 1/3 of the orbit of the Earth? (maybe even getting close to Venus!)

Such a trip would represent the furthest Man has been away from Earth,

it would not have the difficulties of landing on another world (or getting back) and it would be a good test of test of things like radiation out of cislunar space, remoteness from Earth and perhaps technologies like VASIMR and artificial G. Would the average citizen understand that even though the final endpoint of such a trip would be Earth itself, that the journey itself would represent firsts of many kinds? I imagine a trip where humans could see Venus close would re-energize the average person’s enthusiasm for space?

> And as for reproduction in space, why don’t we find out first if it can even happen the “regular” way before we start introducing artificial wombs, frozen gametes, cloning, and whatever else that is still awaiting feasibility.

Even if the “regular way” yields viable babies, there’s still the literally huge issue of mass and hence propellant (ala the rocket equation) and hence time and money. Artificial wombs have gestated rat pups to our equivalent of 31 weeks. Production of viable human embryos from frozen gametes has been established technology for 40 years. Realistic appearing and acting androids are viewable on YouTube. Recorded and replayed android behavior is also viewable on TouTube. Expert dialogue systems are on most smart phones and on certain web pages and continue to improve. So feasible? It is, if we’re fair enough to recognize it.

@ljk

I am well aware that space travel had its foundation in the ballistic missiles and political tensions of the Cold War, but I hardly see how that justifies comparisons between Columbus’s attempt at reaching the Indies and our first space flights. One of my grandmothers was half-Chippewa, and I can’t say I am fond of such comparisons myself.

However, “political correctness qualms” aside , such analogies are clumsy and lazy in the extreme- actually establishing an interplanetary society will probably look a lot more like building offshore oil rigs than anything else. We will probably begin gathering asteroidal material, cometary ices, and collecting plentiful solar energy to build and supply successive series of large space stations. Various scientific expeditions will visit the nearby planets, and maybe some self-sustaining settlements will be built on Mars. This is a frontier for engineers and architects, not conquistadors. This model will extend to the stars.

Once we send expeditions to Earth-like planets, we will have to be careful how we treat them- biological contamination could be a hazard both for the alien ecosystem and the explorers. Possibly we might consider settling a habitable planet with no intelligent inhabitants, but biochemical incompatibilities, dangerous microorganisms, and inhospitable environments could threaten the would-be settlers. By then, humans could be so used to living in ships and stations of various sorts that they wouldn’t even want to settle on a planet. A star with little more than asteroidal rubble and comets orbiting may seem to them a far more inviting vista, offering plenty of raw material for constructing new space stations and starships.

The “Avatar” colonization scenario you present is only one idea, and probably not a very accurate one, for how we may choose to extend our presence to space. I think that after going to all that trouble to establish ourselves as a “space-faring” society, why would we want to ground ourselves onto an alien planet and possibly even loose our spacefaring status after a century-long flight? A steady buildup of space infrastructure in the Sol system is a much more desirable goal, and such an infrastructure can support expeditions further afield. Once a colonization expedition reaches another star, the first goal will probably be to began building up space infrastructure similar to that in Sol system, and that can go on even if no habitable planets are present. Once established, this can be used as a stepping stone for expeditions to still farther stars.

Experimenting with pregnancy in space has some serious ethical concerns regarding the safety of the mother and child. Prolonged exposure to microgravity seriously affects bone and cardiovascular system health, and the fetus might be exposed to hazardous levels of radiation during its vital formative stages- not a good prospect for a developing baby. Microgravity might lead to complications for the mother, as well, although it would at least relieve her of the strain of carrying the child around. I think we will have to wait until we have space stations with artificial gravity and good radiation shielding before we start experimenting with human reproduction in space.

@johnq

I recently read A.E. van Vogt’s The Voyage of the Space Beagle– fun book, if somewhat dated in some parts. If you are on a voyage to the Andromeda Galaxy, or as they call it “the great spiral nebula in Andromeda”, you need to consider the psychological issues of space sex- but A.E. van Vogt simply decrees that the ladies stay home and that the crew of 1000 men be given a drug that eliminates the physical desire for sex, though not the mental and emotional longing for female companionship.

I doubt that would work, even ignoring the blatant sexism of not allowing women to become astronauts- unless all the lady astronauts flew on all-female starships. A.E. van Vogt did mention that the humans were trying to find the best way to structure a space expedition, so maybe the all-male crew was only one of the ideas. Simply putting 500 women and 500 men on the Space Beagle- with the proper contraceptives, of course- would be the simplest solution, but then the term “astro-naughties” would probably become very accurate for these space explorers, at least until Ixtl ruins the dating scene with his obsession with collecting “guuls” for his eggs. ;-)

Conquistadors, refugees, or even well-meaning Fitzroys (captain of the real Beagle, thought he could bring the native Fuegians back into the fold with one missionary) could spell disaster for native aliens. Perhaps the best thing to do is avoid contact- but then again, we may not be able to avoid making contact, especially if they contact us first. Being aliens, we will not be able to predict what they will think or do. Whatever happens, we have to remember that they are aliens with their own world views that probably aren’t compatible with ours.

Seeing what happens when two different species fight over the same territory, I can’t help but worry that contact with space-faring aliens may end up looking like Star Trek‘s Earth-Romulan war. All you see is an alien starship, you have no idea who- or rather what you are fighting, and you are doing your best to vaporize their starship with an atomic space torpedo while they attempt to do the same thing…

I have been thinking a lot about this subject personally. What are the odds that Mars One will actually launch in 2023, or ever? Probably very small, but however slim, it is my last best chance, so if the program moves forward, I will apply to be on the Dutch reality TV show, to hopefully join the “astronaut corps” of 40, for a 10% chance of being in the first 4 to go to Mars, if the funds can ever be raised…

As unlikely as this all is, the mind wanders into all sorts of “what” if scenarios. Even if one survives the 7 month cruise and 26 months on Mars without resupply, there is no guarantee that new supplies will arrive at the next opposition, and if that fails, no hope of surviving until the opposition after that. So healthy people aged at least 50+ seems to be the appropriate crew to be launched on a one way journey with such uncertain prospects. We would all comfort one another, but torrid passion and jealousy would not be an issue.

From the moment of launch, we would no longer be employees, but independent Martian agents. However, we would would need to produce information: science and entertainment for interplanetary trade, to earn resupply cargoes. (Hey Earthlings, send us a greenhouse kit, and we will load whatever you want into your sample return capsule.)

When one thinks about the tedium of spending possibly years confined to eating and sleeping in a space like a camper van, one realizes that leisure time for art, crafts, and music would be essential. We are not just scientific workers, this is now our whole life. Earth entertainments are no longer relevant. I would want at least a harmonica, ukelele, and drumsticks. Also paints and tools to do sculpture, Mars has plenty of rocks to carve and decorate. Is a solar kiln possible for making ceramics, bricks? Is there any possibility of glassmaking?

Finally, how lonely it would be without any animals. We would have to have pets, a small mammal or two, perhaps a small parrot or two, maybe a little tank with fish and turtles. It sounds like madness in such a confined space, but a life sentence to a changeless, sterile environment is even greater madness. Even an inmate on Alcatraz blessed with great scenery and fresh air, still felt the need to care for pets, and adopted wild birds.

I agree with Christopher Phoenix on the idea that interstellar travellers will have more use for asteroidal material than terrestrial planets at their destination. It seems that Earth-analog planets will only be found at a small minority of stars. This means that our descendants will be journeying to stars without Earth-analogs for a long time before one with an Earth-analog comes within range, and that, therefore, when it does, the planet will be more valuable as a subject of scientific study than for colonisation.

Stephen

Joy said on September 12, 2012 at 19:01:

“Finally, how lonely it would be without any animals. We would have to have pets, a small mammal or two, perhaps a small parrot or two, maybe a little tank with fish and turtles. It sounds like madness in such a confined space, but a life sentence to a changeless, sterile environment is even greater madness. Even an inmate on Alcatraz blessed with great scenery and fresh air, still felt the need to care for pets, and adopted wild birds.”

LJK replies:

Actually the inmates on Alcatraz said that the views of San Francisco and all the sounds of the city just 1.5 miles away were more torture than anything else, being able to hear all that freedom so close and yet so far. Prisoners actually requested cells which had no view of the city across the bay.

As for long space voyages, I wonder how much hand-held computer devices and virtual reality will come into play to deter boredom and worse? Already our children no longer have to suffer hours in family car trips just staring out the window, for they have a wide range of audiovisual equipment to keep themselves entertained. I’m old enough to still be amazed at televisions in minivans. :^)

About staying in space versus colonizing a planet: I have wondered about that myself, though who can predict what future generations who have spent centuries moving among the stars might do?

And speaking of Worldship crews, will those who are in the middle of the journey – the ones who never saw Earth and will never see the destination star system – be content with their roles as midwives for the colony’s success? Will it give them a sense of purpose in their lives, knowing that they are making an actual contribution to their descendants? Or will they resent being forced into a life they did not ask for and react in opposition to the original mission goals?

I also have to wonder if humans will ever be truly suitable for interstellar missions, or if they kind of humans that do go to the stars will not be very much like us, having undergone technological, biological, and cultural changes we would consider to be science fiction.

@Joy

I’m not really certain about this information concerning the Mars one projected mission in 2030, but I believe you have the wrong idea concerning what that particular mission is about. As I understand it, the plans that the Dutch have been looking at does not involve an aspect of sending the colonists to Mars with the intention of abandoning them. Rather as I understand it, the idea is to send the colonists on a one-way mission to the planet and resupply them once or twice. The hope I think is that the colonists will become self supporting and won’t require any more assistance (hopefully) from Earth. That’s not to say that if trouble develops they won’t be resupply, what I think they really do hope that the colony will attain the self-sufficiency such that they can do exploration and scientific work, all the while being televised to Earth audiences so that the sponsors can obtain some type of return to sustain the mission. The goal here is NOT to torture the colonist in front of a worldwide TV audience rather it’s meant to allow Earth audiences to follow what’s going on on Mars.

http://www.technologyreview.com/view/429214/space-station-spin-off-could-protect-mars-bound/

Space Station Spin-Off Could Protect Mars-Bound Astronauts From Radiation

Superconducting technology developed for the International Space Station could protect humans on the way to the asteroids or Mars. But will it be worth the cost?

The Physics arXiv Blog

Friday, September 14, 2012

It’s hard to think of many spinoffs from the $100 billion project to build and launch the International Space Station. In fact, there is precious little done on the ISS that isn’t focused on just keeping the thing in orbit.

One exception is the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, which is designed, among other things, to determine whether cosmic ray particles are made of matter or antimatter.

The spectrometer consists of a giant magnet that deflects charged particles and a number of detectors that characterise the mass and energy of these particles. It was bolted to the ISS last year and is currently bombarded by about 1000 cosmic rays per second.

Today, Roberto Battiston at the University of Perugia in Italy and a few pals say that the technology developed for the spectrometer could be used for protecting astronauts from radiation during the long duration spaceflights in future.

The journey to the asteroids, Mars or beyond is plagued with technological problems. Among the most challenging is finding a way to protect humans from the high energy particles that would otherwise raise radiation levels to unacceptable levels.

On Earth, humans are protected by the atmosphere, the mass of the Earth itself and the Earth’s magnetic field. In low earth orbit, astronauts loose the protection of the atmosphere and radiation levels are consequently higher by two orders of magnitude.

In deep space, astronauts loose the protecting effect of the Earth’s mass and its magnetic field, raising levels a further five times and beyond the acceptable limits that humans can withstand over the 18 months or so it would take to get to Mars or the asteroids.

An obvious way to protect astronauts is with an artificial magnetic field that would steer charged particles away. But previous studies have concluded that ordinary magnets would be too big and heavy to be practical on a space mission.

However, superconducting magnets are more powerful, more efficient and less massive. They are much better candidates for protecting humans.

The only problem is that nobody has built and tested a superconducting magnet in space.

That’s where the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer comes in. This machine was designed and built with a superconducting magnet that can operate in space.

Now Battiston and co have used the knowledge and experience from building this machine to study how it could be put to use on a deep space mission for humans. For example, they use the software developed to simulate the behaviour of the superconducting magnets on the spectrometer to study how a human-rated system might work.

This simulates not only the magnetic field but also the forces it generates and how they are distributed, an important consideration in superconducting systems.

In particular, they compare two different designs for the way wires are wound onto the magnet–one using ordinary torroidal windings and another using a double helix-type winding.

Their conclusion is that the double helix offers significant advantages because of the way the forces are distributed within it. These would require less external support, which would reduce the mass of the entire system.

That’s a potentially interesting project–the International Space Station has always been thought of as a stepping stone to the Solar System so it is appropriate that its technology could provide a foundation for future missions.

However, this isn’t the whole story. What Battiston and co fail to mention is that after 15 years of design and testing at a cost of a cool $2 billion, the superconducting magnet system could not be made reliable enough to fly in space. In the end, it had to be hastily replaced with permanent magnets just a few months before the Space Shuttle carted it into space last year.

NASA and other space agencies have always known that sending humans into space is hard and expensive. What they’ve failed to grasp is that they are having to spend more and more to do less and less.

The Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer is a case in point. The only significant science being done on the $100 billion ISS is with the spectrometer. And the only reason it is attached to the ISS is because of the power it was supposed to need for its original superconducting design: only the solar panels on the ISS could provide enough, we were told. The presence of humans is more or less irrelevant.

Maybe future systems could be made reliable enough to protect humans. They might even be made light enough to be launched into space. But it doesn’t look likely that they can be made cheap enough to be justifiable in the short to medium term.

Here’s the bottom line: humans are an expensive cargo that add little if any value when it comes to science in space.

So the message is clear–if we want the best return from our space-bound bucks, we’ll be better of sending robots for the foreseeable future. And they don’t need any kind of magnetic protection–superconducting or otherwise.

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/1209.1907: ARSSEM: Active Radiation Shield for Space Exploration Missions

The above posting by ljk about the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (whose planned-but-not-flown superconducting magnet system could be used to protect human crews from cosmic rays) got me wondering:

Since atomic batteries (*not* RTGs [Radioisotope Thermo-electric Generators]) that employ beta particle radiation sources and dissimilar metal plates have been developed, could similar batteries that would use cosmic rays as the radiation source be used to power spacecraft’s electrical systems? Even if they produced low power levels, they could be used to recharge higher-power conventional chemical batteries, and this arrangement might provide an alternative to RTGs for outer solar system spacecraft.

I have wondered if, besides scientists and technicians, Benedictine monks might make good candidates for long space voyages. My thought was that men who had set aside worldly ambitions might be better able to endure the long periods of isolation such voyages impose on space explorers.

Needless to say, there would of course be overlapping of disciplines. Benedictine space explorers would also need to be engineers, astronomers, physicists, etc. Given the scholarly traditions of orders like the Jesuits and Benedictines, that should not be impossible to achieve.

Sincerely, Sean M. Brooks

Record-Setting Female Astronaut Takes Command of Space Station

by Tariq Malik, SPACE.com Managing Editor

Date: 15 September 2012 Time: 07:13 PM ET

NASA astronaut Sunita Williams, who holds the record for the longest spaceflight by a woman, took charge of the International Space Station Saturday (Sept. 15), becoming only the second female commander in the orbiting lab’s 14-year history.

Williams took charge of the space station from Russian cosmonaut Gennady Padalka, who is returning to Earth on Sunday after months commanding the outpost’s six-person Expedition 32 crew. Williams launched to the station in July and will command its Expedition 33 crew before returning to Earth in November.

“I would like to thank our [Expedition] 32 crewmates here who have taught us how to live and work in space, and of course to have a lot of fun up in space,” Williams told Padalka during a change of command ceremony. She will officially take charge of the station on Sunday, after Padalka and two crewmates board their Soyuz spacecraft for the trip home.

Full article here:

http://www.space.com/17624-female-astronaut-sunita-williams-commands-station.html

James Jason Wentworth: I am pretty sure that the power that could be harvested from cosmic rays is minuscule compared to the power obtained from “betavolt” batteries, which in turn is minuscule compared with that from RTGs, which in turn are anemic compared with reactors. My guess is that these four span at least 10 orders of magnitude in power density.

Sean M. Brooks said on September 16, 2012 at 22:56:

“I have wondered if, besides scientists and technicians, Benedictine monks might make good candidates for long space voyages. My thought was that men who had set aside worldly ambitions might be better able to endure the long periods of isolation such voyages impose on space explorers.

“Needless to say, there would of course be overlapping of disciplines. Benedictine space explorers would also need to be engineers, astronomers, physicists, etc. Given the scholarly traditions of orders like the Jesuits and Benedictines, that should not be impossible to achieve.”

LJK replies:

My view has been for a while now that among the first types of people who will venture to the stars are the strongly religious, whether to avoid persecution and oppression ala the Puritans or to satsify a missionary zeal with whole societies of potential new recruits.

Unfortunately that may also mean cultists, but the Roman Catholic Church in its two thousand year old quest to remain in power may expand into space. Or maybe I am just a huge fan of A Canticle for Leibowitz. :^)

Sean: “Benedictine monks might make good candidates for long space voyages. My thought was that men who had set aside worldly ambitions…”

Some years ago when I spent some time in a hotel in France that was originally a monastery in the middle ages. The owner took us down to the sub-basement and showed us a bricked up narrow tunnel at one end. It used to connect to a convent about 100 meters distant (that building was also still standing), passing under the street and other properties. That the sub-basement was primarily a wine-making workshop would indicate that there were some great parties going on down there several centuries ago.

Similar arrangements were to be found throughout southern Europe.

Sean M. Brooks, I love suggestions that sound ridiculous yet that contain a hint that they might turn out to be correct. I can’t help but reaffirm ljk’s sentiment.

I am fascinated that some religious minded sectors believe in obtaining and storing information as an ends in itself. Further interest is that they can guard it with fanaticism that can never be matched by any pragmatic or practical considerations of the immediate need for survival (as reflected in medieval history or as outlined as a redeemer of future civilisation in ljk‘s beloved “A Canticle for Leibowitz).

I wonder what the “right stuff” really is here?

Hi, “ljk”:

Thanks for your comments.

I would point out that the question of whether there are non human rational beings on at least some planets of other stars has interested some Catholic theologians. Issues like whether non human rational beings have also fallen and how God has provided for their salvation, or whether Christ became Incarnate on other worlds, etc. And the philosophical and theological implications of that question has interested SF writers such as the late Poul Anderson (see short stories of his like “The Problem of Pain” and Chapter 1 of his novel THE GAME OF EMPIRE). See as well CS Lewis’ essay “Religion and Rocketry.”

And, of course, I have read Walter Miller’s A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ and James Blish’s A CASE OF CONSCIENCE.

Sean M. Brooks

Growing up as a Roman Catholic and an amateur astronomer and space and science fiction buff, I was deeply relieved to read in my catechism book that the Church now approved of the idea of extraterrestrial life because God was God and He could do whatever He liked, including making aliens.

At least the Church was finally getting beyond the ancient Aristotlean view that Earth is the only planet in the entire Universe and the only one with any life. There was that declaration by the Bishop of Paris in 1277, if only to make sure that no one, not even Aristotle, could limit the powers of God.

Not quite so long ago, a Jesuit who was also a professional astronomer, said if he encountered an ETI he would among other things try to baptize them.

http://www.beliefnet.com/News/Science-Religion/2000/08/Would-You-Baptize-An-Extraterrestrial.aspx

Which leads me to wonder: If I am thinking that the first human efforts to move into to the wider Milky Way galaxy would include religious groups who might try to convert any other intelligences, would that also be the purpose of alien visitors to our Sol system – assuming that religion is part of the evolutionary development of intelligent beings? Just imagine the “fun” that would be had between some ETI missionaries bent on “saving” an unwashed humanity by trying to get us to worship their deity and the more strongly religious groups of this world.

There are people who think, hope, and assume that ETI can “save” us from our primitive, destructive selves. But do these same people really think about what “saving” us from ourselves implies? And how an alien mentality may have a very different view of salvation.

I have always wondered what an ETI might think of the main symbol of Christianity: A man nailed to a cross. We are told it is about the Son of God making the ultimate sacrifice to save humanity, but you know what they say about first impressions….

Yet another answer to the Fermi Paradox? Nobody wants to deal with the apparently crazy and violent beings of Sol 3 who tortured to death the offspring of the most powerful being in the Universe because, as Douglas Adams so famously once said, he suggested that everyone should be nice to each other.

Designing a Sustainable Interstellar Worldship

Guest contributor Rachel Armstrong introduces Project Persephone, an initiative to design the living infrastructure of a multi-generational starship.

Thu Sep 20, 2012 06:49 PM ET

Content provided by Rachel Armstrong, Project Persephone Lead, Icarus Interstellar

Full article here:

http://news.discovery.com/space/project-persephone-icarus-interstellar-100yss-120920.html

Hi, “ljk,”

Thanks for your comments, even if I don’t quite agree with them. I’ll respond to both your notes here.

First, it was never defined Catholic doctrine or dogma binding on the faithful that this Earth was the only world which existed or was created. So that can be dismissed.

Second, I have heard of the astronomer Brother Guy Consolmagno, SJ. He very kindly sent me via computer his booklet INTELLIGENT LIFE IN THE UNIVERSE? when I could not find it online. It seems to be an expansion of the short article by Dr. Consolmagno which you sent me.

Questions like this has interested me for many years. And I’ve even put together an essay discussing them. Only a “provisional” essay since I’m not quite satisfied with it. In it, I quoted and discussed ideas by St. Paul, C.S. Lewis, and Poul Anderson, etc. I may need to drastically revise it after reading Brother Guy Consolmagno’s booklet. I’m willing to send it to you if you are interested.

C.S. Lewis actually touched on what you mentioned in your last paragraph. We, the people of Earth, may have been quarantined de facto by the vast distances separating us from the other stars lest we corrupt other intelligent beings who have not fallen. Of course, Lewis discussed it far better than this simplistic summary in his essay “Religion and Rocketry.”

Sincerely, Sean M. Brooks

Hi Sean – Yes, I would like a copy of these works, thank you. Are they available online?

While the Roman Catholic Church may not have had a formally official view on alien life, there was a definite impression back in the day that no such beings existed, thanks to ancient Greek guys like Aristotle. His was the official word on science for centuries.

Giordano Bruno may not have been executed because of his support of infinite amounts of life throughout an infinite Universe, but it did not help.

I know growing up, whenever I would bring up the topic of extraterrestrial life, I would often get less than stellar looks and comments from Catholic laypersons and clergy alike. Of course living in a small farming community probably did not help, either. And I will spare you the details of my “debates” with said folks regarding evolution.

Spealing of evolution, I always felt admiration and sympathy for the Jesuit paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin who tried mightily to reconcile his faith with science. He thought all life was working towards what we might call the Omega Point. The Church was not happy with these attempts, but thankfully his literature survives.

I know one reason for this anti-alien attitude was not only the shadow of Aristotle but the view that the Son of God would not be reincarnated countless times to visit new worlds in need of saving and be tortured and executed over and over again. It just seemed like too much. Better there were no aliens than having even alien creatures living in sin somewhere.

Hi, “ljk,”

Again, thanks for your comments. Even though I still disagree with some of them.

I don’t consider the bit about Aristtotle’s views relevant, howerver, great philosopher though he was. For one thing, merely by believing hell and heaven and angels are real things, the Church was saying other worlds and non CORPOREAL rational beings exist. That makes it easier to accept the possibility of other, phyical worlds, existing.

Partly because the 1913 CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA was compiled long before we had any space programs, I looked up there the article on Giordano Bruno. The reasons why he got into trouble with both Protestants and Catholics was for his theological beliefs, not for believing other worlds exist. If interested, you can find the Encyclopedia and article at the New Advent website.

I am a science fiction fan. Believe me, I’ve gotten laughed at by the non SF types when I talk about space and non human rational beings. A lack of imagination is not limited to rural people or Catholics!

Btw, there have been, and are, Catholic SF writers. I need cite only Gene Wolfe or Tim Powers, to name two. And Poul Anderson, agnostic though he claimed to have been, treated the Church wirh respect in his books.

I’m sorry, but I disagree with the analogy you made with Teilhard de Chardin. Because, for one thing, the Church has NEVER condemned evolution as such. The FIRST time she ever mentioned evolution officially came in 1950, 91 years after Darwin’s THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES was published, when Pius XII discussed evolution in his encyclical HUMANI GENERIS. Briefly, the Pope said the Church had no objections to non atheistic forms of evolutionary thought. Or that the human race had multiple origins. You can easily find this document online!

Again, too briefly, Teilhard de Chardin was criticized not for believing in evolution, but for apparently believing in pantheism. And pantheism is obviously a matter of theology and philosophy.

I also disagree with your last paragraph. The Church has never officially denied that corporeal, non human rational beings exist. Because, to date, it is all speculation, either way.

If you send me your email address, I’ll try to send you both Dr. Consolmagno’s INTELLIGENT LIFE IN THE UNIVERSE? (unless you choose to ask him directly) and my own little effort. Simply email me using “Seanmbrook@aol.com.”

Sincerely, Sean M. Brooks

Let me correct myself. In the paragraph mentioning Pius XII, I should have said the Church did not agree with those who argued the human race had multiple origins. That is, polygenism.

Sean M. Brooks

How gender was viewed in long space missions in the 1950s:

http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com/paleofuture/2012/10/sex-and-space-travel-predictions-from-the-1950s/

Review: The Spacesuit Film

Long before the first spacewalk or even first human spaceflight, movies depicted spacesuited astronauts exploring the solar system. Jeff Foust reviews a book that offers a critical history of this specific genre of science fiction films.

Monday, November 12, 2012

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2185/1

This quote from the above linked Space Review article sums it up beautifully in reagrds to our future in the Milky Way galaxy and beyond:

“Humanity today essentially faces two possible futures: We can either permanently remain on Earth, and permanently remain the same, or colonize space, and transform ourselves into inhabitants of space,” he writes.

“Star Trek falsely argues that no choice need be made: We can conquer the universe, and we can also remain exactly the same as we are now.”

When the steel hand wavered and an opportunity was lost

When the “Mercury 13” group of prospective women astronauts sought recognition from NASA a half-century ago, one would have imagined that a pioneering female pilot, Jacqueline Cochran, would have supported them. Billie Holladay Skelley looks at why Cochran instead failed to back their efforts.

Monday, November 26, 2012

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2193/1

The Overview Effect at 25

Twenty-five years ago, a book argued that those who flew in space experienced a radically altered perception of the Earth.

Jeff Foust talks with Frank White, who wrote about the Overview Effect in 1987 and continues to study it today.

Monday, December 3, 2012

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2195/1

What Does Space Travel Do to Your Mind? NASA’s Resident Psychiatrist Reveals All.

Esther Inglis-Arkell

Space travel is tough on the human body. But what does it do to the human mind? Gary Beven, a space psychiatrist at NASA, answers our questions about how humans adapt to space, and what we have to do to go to Mars.

Doctor Gary Beven has to have one of the most surprising careers in science. As he puts it, he’s “the fifth full-time NASA civil servant psychiatrist since the beginning of the human space program, the first being hired in the 1980s at the onset of the Space Shuttle Program.”

Becoming an astronaut is a mentally, emotionally, and physically demanding job that’s done at high risk around insanely expensive equipment. It pays to see how this job can be made psychologically easier for everyone involved.

But how does one even start out as a space psychiatrist? I asked Doctor Beven.

Full article here:

http://io9.com/5967408/what-does-space-travel-do-to-your-mind-nasas-resident-psychiatrist-reveals-all#13554082355012

‘Overview’ is a short film that explores this phenomenon through interviews with five astronauts who have experienced the Overview Effect. The film also features insights from commentators and thinkers on the wider implications and importance of this understanding for society, and our relationship to the environment.

Full article here:

http://moonandback.com/2013/01/15/a-short-film-looks-at-the-overview-effect/

What has and has not changed since cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin did that one circuit of Earth aboard Vostok 1 fifty-two years ago this month:

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/04/130412-space-travel-technologies-yuri-gagarin/

Those magnificent spooks and their spying machine: The spies help rescue Skylab

Forty years ago this month, NASA launched its Skylab space station, only to find the station was damaged during its ascent to orbit. Dwayne Day examines the little-known role played by a spy satellite to help NASA assess the damage to Skylab before launching a repair mission.

Monday, May 20, 2013

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2299/1