We’ve found our share of unusual planets in the short time since actual observations could be made. A decade ago, it would have been hard to come up with anything more unexpected that a ‘hot Jupiter,’ orbiting so close to its parent star that its orbital period is measured in scant days. Add in ‘super Earths’ around dim red dwarfs and pulsar planets (actually the first type of exoplanets to be discovered) like those around the pulsar PSR 1257+12, and you have a bestiary of odd objects in the making.

And now an outburst of gamma and X rays from the direction of the galactic center, one first detected with the Swift satellite’s Burst Alert Telescope, gives promise of yet another kind of object. Pulsing in X rays 182.07 times per second, the source is clearly a ‘millisecond’ pulsar, a neutron star spinning at fantastic rates. Precise studies of the X-ray timing data have revealed the existence of a low-mass companion with a minimum mass of seven Jupiters, but there is wide play in that estimate because of our lack of information about the system’s orbital inclination.

A pulsar planet? Evidently not. The formation scenario goes like this: The original system would have consisted of a massive star and a smaller one not much larger than our own Sun. When the larger star exploded as a supernova, a neutron star was left behind. The second star, moving toward red giant stage, caused the two objects to become embedded in what was now an extended stellar envelope. That would have ejected the envelope itself while drawing the two stars nearer to each other.

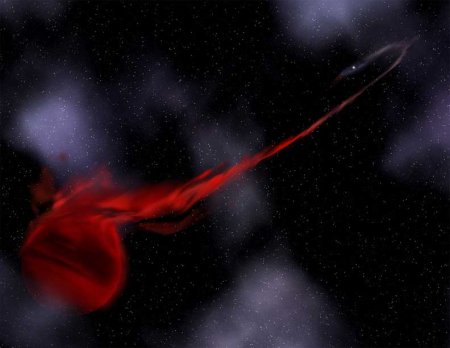

Image: In this artist depiction of the SWIFT J1756.9-2508 system, the foreground object is the planet-mass object. The pulsar, located at the upper right, is tidally distorting the companion into a teardrop-shaped object, and ripping gas from it. This material flows in a stream toward the pulsar and forms a disk around it. Eventually, enough gas builds up in the disk to produce an outburst bright enough to make the system visible from Earth. Credit: Aurore Simonnet/Sonoma State University.

So we’re looking not at a planet, despite its size, but the remains of a companion star, says Christopher Deloye (Northwestern University):

“Despite its extremely low mass, the companion isn’t considered a planet because of its formation. It’s essentially a white dwarf that has been whittled down to a planetary mass.”

And one that’s been through a hell of a beating. The cause of the eruption that called this system to our attention may be siphoning of gas from the white dwarf survivor. Flowing into a disk around the neutron star, the gas could trigger the occasional outburst. Because the object, known as SWIFT J1756.9, has never been known to erupt before, all bets are off as to how frequent an occurrence such events may be.

Centauri Dreams‘ note: Those bestiaries I mentioned earlier were wildly popular in the European Middle Ages, presenting (often in beautifully illuminated manuscripts) stories about various plants and animals, some of them mythic, as seen through the lens of current science and religion. Today we assemble collections of astronomical information that put the wildest imaginings of medieval travelers to shame. Each new planetary discovery (and, as we’ll see tomorrow, each new analysis of existing planetary data) sketches places that jog the imagination, and may serve, as did their medieval counterparts, to invigorate not only science but literature and art.

Image: The fabulous, mythical griffin seizing another animal for its dinner. Griffins, unicorns and other such creatures fired the medieval imagination. Will our growing catalog of extrasolar systems have the same effect upon a jaded public? Source: The Harley Bestiary (Harley MS 4751), an English manuscript ca. 1230-40 now preserved in the British Museum.

The paper on this new pulsar work is Krimm et al., “Discovery of the accretion-powered millisecond pulsar SWIFT J1756.9-2508 with a low-mass companion,” accepted for publication in Astrophysical Journal Letters (abstract).

Planet formation around stars of various masses: The snow line and the frequency of giant planets

Authors: Grant M. Kennedy, Scott J. Kenyon

(Submitted on 4 Oct 2007)

Abstract: We use a semi-analytic circumstellar disk model that considers movement of the snow line through evolution of accretion and the central star to investigate how gas giant frequency changes with stellar mass. The snow line distance changes weakly with stellar mass; thus giant planets form over a wide range of spectral types. The probability that a given star has at least one gas giant increases linearly with stellar mass from 0.4 M_sun to 3 M_sun. Stars more massive than 3 M_sun evolve quickly to the main-sequence, which pushes the snow line to 10-15 AU before protoplanets form and limits the range of disk masses that form giant planet cores. If the frequency of gas giants around solar-mass stars is 6%, we predict occurrence rates of 1% for 0.4 M_sun stars and 10% for 1.5 M_sun stars. This result is largely insensitive to our assumed model parameters. Finally, the movement of the snow line as stars greater than 2.5 M_sun move to the main-sequence may allow the ocean planets suggested by Leger et. al. to form without migration.

Comments: Accepted to ApJ. 12 pages of emulateapj

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0710.1065v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Grant Kennedy [view email]

[v1] Thu, 4 Oct 2007 18:17:01 GMT (50kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0710.1065

Characterization of the long-period companions of the exoplanet host stars: HD196885, HD1237 and HD27442

Authors: G. Chauvin, A.-M. Lagrange, S. Udry, M. Mayor

(Submitted on 31 Oct 2007)

Abstract: We present the results of near-infrared, follow-up imaging and spectroscopic observations at VLT, aimed at characterizing the long-period companions of the exoplanet host stars HD196885, HD1237 and HD27442. The three companions were previously discovered in the course of our CFHT and VLT coronographic imaging survey dedicated to the search for faint companions of exoplanet host stars. We used the NACO near-infrared adaptive optics instrument to obtain astrometric follow-up observations of HD196885 A and B. The long-slit spectroscopic mode of NACO and the integral field spectrograph SINFONI were used to carry out a low-resolution spectral characterization of the three companions HD196885 B, HD1237 B and HD27442 B between 1.4 and 2.5 microns. We can now confirm that the companion HD196885 B is comoving with its primary exoplanet host star, as previously shown for HD1237 B and HD27442 B. We find that both companions HD196885 B and HD1237 B are low-mass stars of spectral type M1V and M4V respectively. HD196885 AB is one of the closer (~23 AU) resolved binaries known to host an exoplanet. This system is then ideal for carrying out a combined radial velocity and astrometric investigation of the possible impact of the binary companion on the planetary system formation and evolution. Finally, we confirm via spectroscopy that HD27442 B is a white dwarf companion, the third one to be discovered orbiting an exoplanet host star, following HD147513 and Gliese 86. The detection of the broad Bracket gamma line of hydrogen indicates a white dwarf atmosphere dominated by hydrogen.

Comments: 6 pages, 3 figures and 3 tables

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0710.5918v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Gael Chauvin [view email]

[v1] Wed, 31 Oct 2007 17:56:41 GMT (35kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0710.5918