The Italian contribution to the interstellar effort has been substantial, and I’m pleased to know three of its principal practitioners: Claudio Maccone, Giancarlo Genta, and Giovanni Vulpetti. It was with great pleasure, then, that I took Roberto Flaibani up on his offer of appearing in his excellent blog Il Tredicesimo Cavaliere (The Thirteenth Knight). Roberto had translated several Centauri Dreams articles into Italian in the previous year and was now looking for comments on the ramifications of human contact with extraterrestrials as we push into interstellar space. This article on Star Trek’s Prime Directive grew out of our talks and became part of a broader discussion of related articles on Roberto’s site. I thank him for continuing to translate my work into Italian, and now offer the original essay to Centauri Dreams readers.

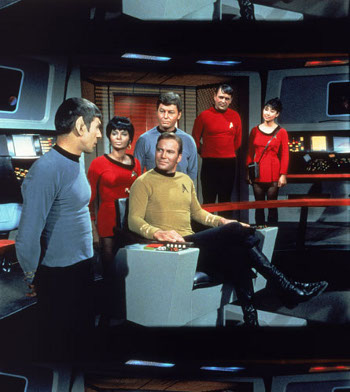

I should probably throw in a qualifier — I’ve always enjoyed Star Trek but am hardly a rabid fan, getting most of my science fiction not from film or TV but novels and short stories. So this is a bit of a jeu d’esprit, one that acknowledges that the show has indeed spun out provocative and often controversial scenarios.

The Prime Directive embodies a flawed but useful ethical principle that should remain in place, though not without extensive revision. To understand why we need to re-think some aspects of the Prime Directive, let’s consider the context in which it operates. Because it grew out of ‘Star Trek,’ we have to posit a universe much like that one to illuminate the regulation’s strictures. Let’s assume, then, that humans become a spacefaring civilization on not just an interplanetary but an interstellar scale. That means that through whatever means, we have acquired ways of getting to the stars in short time frames, and that an organization has emerged within which this exploration continues, an analogue to the Federation behind the directive.

Why would the Prime Directive emerge in the first place? Here it is important to remember that in the ‘Star Trek’ universe, the directive is actually a regulation that applies only to Starfleet. Indeed, the series shows us that if a citizen of the Federation has decided on his or her own volition to interfere with another civilization, Starfleet is powerless to prevent such actions. The regulation doubtless was called for because the outermost wave of human expansion would be the exploring arm embodied in Star Fleet itself. What happens after a given region of space is first charted and explored is up to individual action, but the people most likely to be involved in first contact with an alien culture are those operating under Federation regulations.

All of this seems like logical extrapolation, and it is a tribute to the ‘Star Trek’ universe that despite the number of television episodes in various configurations and movies using many of the same characters, the storyline has been kept relatively consistent. If we ever do develop a way of sending human crews to other worlds, we will ponder the question of how we interact with any intelligent species we find there. And it’s likely we’ll consider a principle something like “the right of each sentient species to live in accordance with its normal cultural evolution,” a phrase pulled from the text of the Prime Directive. What we are looking at is the development of ‘metalaw,’ a term devised by attorney Andrew Haley in 1956 to specify a system of laws that apply not just to human beings but to all relationships between intelligent species.

Evolving Metalaw and Human Culture

Why not simply resolve to treat alien cultures using the principles of the Golden Rule — treat aliens as we would wish to be treated by them? Haley went on to point out the problem with this approach in a paper called “Space Law and Metalaw – A Synoptic View,” recognizing that aliens are different from ourselves in ways we may not begin to understand. Treating them as we would like to be treated might cause them injury or even destroy them. Haley revised the Golden Rule this way: “Do unto others as they would have you do unto them.” Robert Freitas, who has written thoughtfully on the subject of metalaw, notes that this ‘Great Rule’ has its own problems: “…in practice the Great Rule would be as difficult to apply as the concepts of noninterference and physical security. If we are to ascertain the desires of the other party, we must interact with them to a certain degree – and this may cause sociocultural damage. We still are left with the problem of developing nonconflicting, serviceable metalegal rules.”

We are in the earliest stages of developing ‘metalaw’ today, but a widening sphere of human activity among the stars will eventually force us to move the concept forward. Aerospace engineer Giancarlo Genta (Politecnico di Torino) has examined these questions in his book Lonely Minds in the Universe (Copernicus, 2007), studying the entire question of whether an alien being in today’s world could be considered a ‘person.’ An interesting legal issue would arise if we suddenly found ourselves face to face with a being from another world. We may believe in extending equal rights to all humans no matter their origin, but an extraterrestrial who walked out of a spaceship after landing on Earth would not necessarily be recognized by law as a ‘person.’ Would this creature be considered an animal? If so, would an alien animal have rights under existing law?

The Prime Directive can be assumed to have grown out of discussions exactly like these, and it hinges on the extension of the idea of personhood to alien intelligences. In his paper “Metalaw and Interstellar Relations” (cited above) Robert Freitas sees two routes to personhood:

- The use of a clear morality; i.e., the ability of the beings in question to make moral or ethical judgments, even if those judgments do not necessarily coincide with our own

- The presence of self-awareness, of being separate from one’s surroundings.

The presence of either morality or self-awareness is seen as the key to personhood. Here we seem to be splitting hairs in legalistic fashion, but the issue is important because human law revolves around the concept of the person. Metalaw, in other words, leads us invariably to the thinking that leads to the Prime Directive, which we can now quote in more extended form:

As the right of each sentient species to live in accordance with its normal cultural evolution is considered sacred, no Star Fleet personnel may interfere with the normal and healthy development of alien life and culture. Such interference includes introducing superior knowledge, strength, or technology to a world whose society is incapable of handling such advantages wisely. Star Fleet personnel may not violate this Prime Directive, even to save their lives and/or their ship, unless they are acting to right an earlier violation or an accidental contamination of said culture. This directive takes precedence over any and all other considerations, and carries with it the highest moral obligation.

A Silence Between Civilizations?

We now find ourselves in a quandary, for the Prime Directive must be interpreted, just as any body of law or regulation must be understood and acted upon by those affected by it. If we read the text closely, we have no choice but to conclude that the only contact possible between two alien civilizations would happen when the two civilizations are at precisely the same point of development, or as Giancarlo Genta phrases it, the same cultural level. A right is assumed in the Prime Directive for each species to proceed through a ‘normal’ cultural evolution, one which cannot be interfered with by introducing superior knowledge or technologies.

A civilization less advanced than our own in terms of technology, then, would be one we could not contact directly. A civilization more advanced than our own would, if acting under the principles of a similar Prime Directive, be unable to contact us. If the Prime Directive were a universal principle, no species would be able to contact another unless it encountered one so similar to itself that the contact would be considered harmless. Given the wide variation in stellar ages around us in the Milky Way, it seems spectacularly unlikely that we would find a species this similar to ourselves, and all studies of alien cultures would have to be conducted with maximum secrecy to avoid contaminating the alien civilization in question.

This seems an unwise outcome on various levels, but there’s more. What do we mean by the ‘same cultural level?’ Culture is what we recognize around us in the form of the familiar accouterments of society and the technologies we use to provide and service them. But the very idea of an alien culture presupposes a development unlike our own. We could not assume that a culture that seemed similar to our own at the level it was at in the time of ancient Greece would necessarily undergo a similar period of imperial expansion on its planet, a gradual awakening to other cultures across its oceans, a period when learning was lost and an eventual renaissance. Nor could we assume that the beings who live within this culture operate with the same set of principles that we do, or that they would develop technologies comparable to our own.

Note the other flaw in the Prime Directive statement above. We are told that interference consists of introducing superior knowledge, strength, or technology to a world ‘whose society is incapable of handling such advantages wisely.’ The statement implies that if a society is deemed capable of handling these advantages with wisdom, the strictures of the Prime Directive to not apply. But who is to make the decision as to the wisdom of an alien civilization, and how accurate can such an assessment be given the short periods involved in a first contact scenario? And what does the Prime Directive mean by not interfering with the ‘normal and healthy development’ of another culture? To understand what is normal and healthy for an alien civilization may be an impossible accomplishment, and certainly not one we could achieve without extensive study. No, the Prime Directive binds us too severely and limits any contact.

More Supple Rules of Contact

Where to go from here? We need a revised Prime Directive based on an evolving metalaw, one that recognizes that each encounter with an extraterrestrial civilization is going to be different from any other. Genta cites the eleven rules of metalaw compiled by the Austrian lawyer `Ernst Fasan, drawing on the earlier work of Andrew Haley. These are drawn from Fasan’s book Relations with Alien Intelligences: The Scientific Basis of Metalaw (1970), and contain the seeds of a future Prime Directive that should prove more flexible:

1. No partner of metalaw may demand an impossibility.

2. No rules of metalaw must be complied with when compliance would result in the practical suicide of the obliged race.

3. All intelligent races of the Universe have in principle equal rights and values.

4. Every partner of metalaw has the right to self-determination.

5. Any act that causes harm to another race must be avoided.

6. Every race is entitled to its own living space.

7. Every race has the right to defend itself against any harmful act performed by another race.

8. The principle of preserving one race has priority over the development of another race.

9. In case of damage, the damager must restore the integrity of the damaged party.

10. Metalegal agreements and treaties must be kept.

11. To help the other race by one’s own activity is not a legal but a basic ethical principle.

Here we have a set of guiding principles that do not exclude contact between civilizations of different levels of development and complexity. Instead, Fasan’s ideas form a framework that a future commander of an interstellar mission could consult to make decisions about the level of contact appropriate for that situation. Fasan cannot answer all our questions — in particular, we have the conundrum that the ethical concepts embedded here may be profoundly anthropocentric, and we certainly have no idea whether other intelligent races would agree or abide by such ideas. But the scant work that has thus far been done on metalaw points us to the need for an enhanced, more carefully thought-out Prime Directive, one that does not entangle an exploring party far from home with legalities that could compromise a beneficial first contact.

Here it is time to quote Genta directly:

Such rules are without doubt a good starting point on which to build the laws and ethics or relationships between species, but they have been elaborated by one of the sides only — and it could not be otherwise, since it is not even certain that the other sides exist. Moreover, if it is true that the other species with which we could come in contact are much more ancient than ourselves, it is likely that they already faced this problem and established rules for relationships among species.

The reality is that as we expand to nearby stars and beyond, we will learn from our early contacts with other civilizations — if indeed they exist — and shape our metalaw flexibly from each of these encounters. Metalaw cannot be other than an evolving set of principles, incapable of setting down as a Prime Directive that does not grow with our knowledge over time. The Prime Directive offers us a wonderful way to consider the issues. But we need to be aware that it is a template only, and that what we find among the stars will help us shape its future direction. We must also be thinking about these matters long before we actually get to the stars. As Robert Freitas reminds us, “When intelligent extraterrestrial life is discovered, mankind must be prepared, for in all of human history there will be but one first contact.”

References

Fasan, E, Relations with Alien Intelligences: The Scientific Basis of Metalaw, Berlin Verlag, Berlin, 1970. See also his paper “Discovery of ETI: Terrestrial and Extraterrestrial Legal Implications,” Acta Astronautica 21 (2) (1990), pp. 131-135.

Freitas, R, “Metalaw and Interstellar Relations,” Mercury 6 (March-April, 1977), pp. 15-17 (available online)

Genta, G. Lonely Minds in the Universe. New York: Copernicus, 2007.

Haley, A “Space law and Metalaw – A Synoptic View,” Harvard Law Record 23 (November 8, 1956).

The sheer vastness of space would in itself guarantee the flexibility by making it impossible to enforce rigid laws. It is, after all, a whole different thing to track someone down in three dimensions as in space than in the two Earth police are used to. The practical impossibility of such enforcement would, combined with the possibility of reverse-engineering, create an extreme caution against conflict. A flexible de facto Prime Directive would be on the lines of “share primarily technology that can be used to satisfy all parties, i.e. post scarcity technology, and wait a while with sharing technology more useful for violence”. As for the question of whether an alien landing on Earth would legally be considered a person, I am not going to delve into an off-topic evolutionary discussion about how much of “humanness” is results of or prequisites for the evolution of intelligence (which would be too uncertain to base any general assumptions on anyway), but stop at remarking that it shows that rigid laws have no chance in the interstellar era.

An extremely interesting article, highlighting some genuinely profound questions. It is interesting to reflect on the possibility that in the unlikely event that we are the first advanced civilisation to emerge in our part of the universe then we may well eventually create a legal framework that effectively ensures any future emerging civilisations we encounter experience a ‘great silence’ during their dangerous period of early development. There is certain irony to considering how they may well spend considerable time pondering their version of the Fermi Paradox!

My god! Spock’s tits are bigger than Uhura’s! Is this a species thing?

And McCoy and Scotty (and the red-shirt girl) are staring at them! How can one remain emotionless at such times?

I’ve always wondered about the Prime Directive. Seems like every time they took a step on an alien world they were mucking with the thing. I always figured it’s main use was to complicate the plot when required.

Actually while thinking about it is a good thing I suspect that before we commence to interfering with alien life we should at least figure out how to get to the Space Station.

Are there any existing laws in place that would restrict humans from colonising Mars if we were to find microbial life there that would be adversely affected by our presence?

Good article. Just a thought to ponder, just because a species has mastered interstellar travel, doesn’t mean it’s overcome all the problems on it’s planet of origin before doing so. Imagine if on Earth the Nazis won WW2 and expanded through Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas? If we grew up with nazi ideals and ethics. We’d still be pursuing space travel, we would regard alien species differently and our encounters with alien species would have turned out different. Now imagine if on the planet of origin, aliens had a less than desirable political system that was more hostile, less ethical and moral (by our standards). or they may have made better deceptions leading up to their technological breakthroughs that allowed for interstellar travels. Who knows.

For discussion: Isn’t earth our best test ground for “metalaw”? To start an exercise shouldn’t we try to make the UN (for nations) or a similar structure for etnicity (dangerous as proven in the past) follow the 11 metalaws? If that does not work, how can we expect it to work for aliens in interstellar relations? What role may commonality vs. distinction (maybe co-dependency) play in metalaws?

Honestly, I think the Prime Directive was just a drama-inducing plot device. You’re kidding yourself if you think that uplifting a tribal society to our own level is inherently a bad thing. Look at the traditions of half the stone age cultures that were contacted by Europeans, cannibalism, human sacrifice, infanticide as birth control, starvation, warfare, slavery… The list goes on.

Metalaw is all fine and good, but there’s always going to be an intergalactic equivalent of an ambulance chaser seeking out primitives.

Also, I don’t see how The Culture’s (from Iain M. Banks) method of gleefully manipulating less advanced civilizations to keep them from self-destructing is any less valid.

I always saw the Prime Directive as an application of Primum non nocere, “First, do no harm.” If you’re interacting with a newly discovered alien intelligence, how do you know you’re not going to do more harm than good? If leaving them alone is an option, perhaps that’s the best option to avoid violating metalaw #5. Until they build starships. Then you might want to warn them about the Klingons.

I am pretty sure Gene Roddenberry picked up Prime Directive from modern science fiction prose. Wiki cites Olaf Stapledon and L. Sprague de Camp, but I am not sure how well researched Wiki articles are. I can’t cite a particular story , but I am pretty sure the idea appeared in modern SF prose. My goodness, almost every idea an SF writer could use was probably used up by 1960.

One notes that the young Asimov’s reluctance to use aliens at all (by the by Asimov had a reluctance to use them besides John Campbell’s prejudices.)

Clarke’s best aliens are either transcendental (Childhoods End ) or indifferent , Rendezvous with Rama.

I am almost sure the Prime Directive was a reaction to European conquest and colonization. A model many SF writers used, Wells had more than tongue-in-cheek when he wrote War of the Worlds.

Instead of “concepts embedded here may be profoundly anthropocentric”… I would say concepts embedded in a past and present are a profound anthropocentrism not applicable to even us as an unpredictable sociocultural entity when we become starfaring.

One guy has us all trumped when it comes to thinking about the interaction of a human a alien society , that is Fredric Brown.

His Martians, Go Home is about as sly a commentary on how unknowable we could be about an alien culture.

From the Wiki entry:

“Unlike most fictional Martian invaders, the Martians that Brown writes of don’t intend to invade Earth by violence; instead, they spend their wakeful hours calling everyone ‘Mack’ or ‘Toots’ (or some regional variation thereof), heckling theatre productions, lampooning political speeches, even providing cynical colour commentary to honeymooners’ frustrated attempts at consummating their marriage. This nonstop acerbic criticism stops most human activity and renders many people insane, including Luke, whose stress-induced inability to see the little green maligners divides opinion on whether he should be considered mad or blessed.”

I am sure Fred Brown is smiling down on us all.

“4. Every partner of metalaw has the right to self-determination.”,

Good grief! could you get more anthropocentric if you tried? That is equivalent to saying that benevolent rule and living happily in a well constructed legal environment are trivial concerns compared to the benefits of living in a monstrous dictatorship, simply because its rulers know you wants before they ignored them.

It is true that humans tend to develop the Stockholm Syndrome and worship the very ground our dictators work on. Long-term torture victims also often develop a mental bond with their torturers. These explain why humanity would covet point 5, but would even one other sentience concur?!

It gets even more complicated. For example, what if we, as a space-faring race, come across a culture organized socially along the lines of ants or bees, where the vast majority of beings are self-aware but of low intelligence and are only capable of the menial tasks set for them by a small minority of highly intelligent beings of the same species who rule over them?

Fine, we may say, if their society is the product of millions of years of evolution, then while we might feel sorry for the worker-aliens, but as long as they weren’t being maliciously mistreated, I doubt we would want to interfere.

But then what happens if we discover that, in fact, the worker caste wasn’t the product of evolution after all, but the result of a genetic engineering program from a just a few decades back that had been forced upon the main population? What would be our moral obligation to the worker-caste be now?

And, what if, instead of happening just a few decades ago, the aliens had performed the genetic engineering two thousand years ago? Does that change the moral equation?

Sticky questions indeed.

A great, thought provoking article and some really good comments.

The problem I see with all this is that the attorney class is probably already drooling over their proceeds from the mitigation process. I think the best idea would be to keep it as simple possible, or not to have a prime directive at all. “First, do no harm” is a great place to start, and to end. At least in the anthropocentric realm, when we develop a ‘government of laws’, the lawyers end up in charge.

Of course someone has to be in charge, but, as Martin J. Sallberg stated in the first comment “The sheer vastness of space would in itself guarantee the flexibility by making it impossible to enforce rigid laws”. Darth Vader and the Emperor would be lost in that vastness and perhaps that would be best.

All the above is based on completely irrelevant fiction. As one commenter suggested, it is based on the experiences of the colonialism of one human culture by another and the 20th century reaction against . If we ever contacted any ETI at all, which is astronomically unlikely, they would be hundreds of millions if not billions of years older than us. We wouldn’t even be ants, we’d be mere slime. Human law and ethics would be irrelevant, much less issues of 20th century interhuman colonialism. And their law would be preposterous if it recognized us as anything remotely resembling “equals”.

@Mike Walker

“It gets even more complicated. For example, what if we, as a space-faring race, come across a culture organized socially along the lines of ants or bees, where the vast majority of beings are self-aware but of low intelligence and are only capable of the menial tasks set for them by a small minority of highly intelligent beings of the same species who rule over them?”

Sort of like us now…. except, it is not the intelligent but the wealthy.

Reflecting on this interesting article I was reminded of the anthropecentric basis of both our legal systems and our society more widely, including the concept of sovereignty. Others above have also mentioned this point.

I strongly recommend reading the short story “Three World Collide”, which can be found here: http://lesswrong.com/lw/y4/three_worlds_collide_08 It covers some of the same ideas as discussed in this article, although under the term metaethics rather than metalaw. This story doesn’t shy away from exploring how contact between civilisations might go disastrously wrong, even with good will and negotiation from all parties.

My own view on this is that contact between civilisations should almost always be a slow affair. A more technologically advanced culture should always assist a less advanced one, and possibly meddle in their affairs whether with consent or not, depending on circumstance, but this process should have built in and enforced slow pace. Rapid changes to a society lead to instability and can cause greater problems than they solve. First contact law should take that role as a limiter of hasty action.

@Rob Henry: I did not want to slip into discussions about how much of “humanness” is due to intelligence, but your comment about “Stockholm syndrome” forces me to. Any brain capable of circumventing unplanned obstacles (which is necessary to circumvent unplanned obstacles) works by storing information in a way that allows spontaneous pattern emergence from examples. That is accomplished by building sideways connections between different neural pathways, forming a real brain instead of a sum of innate reflexes that can at most be strengthened or weakened by learning. In a real brain, abstract conceptualization is an inevitable emergent spandrel of associative learning. Through the evolution of brains, the connection network increases, which makes the associative-abstractive patterns more precise, increasing situation awareness. For instance, baboon males stop fighting for females through conscious choice if they are placed in a “monkey culture” where the females are not impressed by violent males, and orangutans are usually solitary but form groups in times of rich fruit supply because they are too situation-aware to be typologized as “social” or “solitary”. Apparently dysrational behavior in humans is due to dualistic education that separates theoretical knowledge from practical ditto, creating an illusion of a demarcation between “conscious” and “subconscious”. Consider that most children appear to lose their ability of scientific investigation when they begin school. So-called “cultural universals” should therefore be explained as patterns of situational pragmatism, not as mindless biocomputation as evolutionary psychologists do. Thinking that “Stockholm syndrome” is a species-specific characteristic is therefore a fallacy.

Interesting, but perhaps a tiny bit premature or too narrowly focussed, in view of what we are most likely to find with regard to planets and life;

What I mean is, it is most likely that we will find many, many more planets with non-sentient and even only primitive (single-celled) life for every planet with sentient life.

Therefore, I think any Prime Directive, which is basically a set of guidelines on (non/limited) interference, should be expanded to comprise any living planet, maybe even not-yet-inhabited (primordial, potentially) habitable terrestrial planets.

In other words:

– How to deal with any planet (even when just visiting).

– How to deal with any habitable planet with regard to terraforming and colonizing.

– How to deal with a planet with ‘primitive’ life.

– How to deal with a planet with ‘advanced’ life.

– How to deal with a planet with intelligent/sentient life (also budding intelligence, sentience and civilization).

– …

Also raises the issue of the definition of intelligence and sentience, etc. (E.g. chimps, dolphins, early hominids).

Although not considered one of the better episodes of the original Star Trek series, “The Apple” delves into the very issues of this article, when the crew of the USS Enterprise finds a tropical planet with a primitive humanoid society kept in perfect health and safety by an advanced machine intelligence called Vaal, which they basically treat as a god. The natives never age and do not reproduce (or even know how to). Their culture, such as it is, has not changed in thousands of years.

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/The_Apple_(episode)

To quote from the above link to the Memory Alpha post on the 1967 episode:

“McCoy joins them and complains to Spock that Vaal is depriving the planet’s inhabitants of their right to “a free and unchained environment” and an opportunity for growth. Spock argues that McCoy is unfairly applying Human standards to non-Human cultures, and that humanoids also have the right to choose a system that works for them.”

And then this quote, also from the same source:

“While the others sleep, Kirk and Spock discuss the situation. Kirk has decided that he agrees with McCoy: The villagers’ society is completely stagnant, and exists only to service Vaal. Spock warns that interfering with Vaal would violate the Prime Directive.”

While the Enterprise officers are having this discussion, Vaal has instructed the natives to kill the landing party and how it should be done. The natives have never killed before and Vaal provides no ethical or moral guidance on the act, only that it needs to be done to maintain the status quo. FYI – This is the episode where four redshirts get bumped off, three by the planet via Vaal and one by a native via Vaal’s directive.

In the end, Vaal is deactivated and the natives now get to run their own lives, presumably with a little guidance to get things started by Federation personnel who specialize in uplifting young societies.

Of course the reality of such things in our galaxy may not go like this at all. I bring up again the example of Solaris in Stanislaw Lem’s SF novel of the same name. This “living ocean” is so alien that the humans who have studied it for centuries barely grasp more than the basics of what Solaris is all about. A Prime Directive here has little meaning, except that in this case it is the human scientists who seemed to be the more affected party.

Clearly a seriously advanced ETI will also not be affected by any Prime Directive we could come up with. It seems more likely that we are the focus of a PD by others in the galaxy, to give one time-worn answer to the Fermi Paradox (the Zoo Hypothesis). Although it is certainly imperfect, we are aware of the concept of alien life and interstellar travel, so I wonder what it will take for an advanced ETI to make contact with us? Or are they waiting for our superior successors, which we may be the creators of.

There may not be anything like Solaris in our reality, but it does give one an idea of what we may really encounter out there and why there probably won’t be anything like a United Federation of Planets, unless all its members are humans and they can maintain some forms of consistent contact across the stars.

Based on several comments in this thread, perhaps our first encounter with ETI will be with their equivalent of lawyers. Seeing how quirky life can be on this world on a daily basis, somehow that just seems possible. Besides, current SETI is designed to find beings not terribly dissimilar from ourselves, so we may just get our wish.

Given the time/distance involved. Given the Fermi Paradox. The alien civilizations we are most likely to meet in the next 10000 years will be human. Descendants of humans that have previously colonized a star system, built a civ and became Star Faring themselves.

Imagine Genghis Khan with an anti-matter drive.

Interesting. The recent novel “Count to a Trillion” (http://www.amazon.com/Count-Trillion-John-C-Wright/dp/0765329271) had some interesting ideas about an alien game theory calculus that modeled relationships between civilizations. In the novel, these relations were not particularly nice (no “Prime Directive”). But the discussions of game theory, economics, and vast scales of time and space made this a good read, and a plausible way of thinking abut these issues.

So, let’s see some game-theory and economics applied to the problem. What happens in political relationships with vast differences of power (command over matter and energy), vast time scales (shaping how “iterative interactions” work out), etc. Could be some fascinating research!

Also note! The Fermi Paradox is discussed in the Atlantic:

http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/01/what-happened-before-the-big-bang-the-new-philosophy-of-cosmology/251608/

If E.T. exists, he’s avoiding us, cosmic number-crunchers say

Math suggests there’s no way advanced civilizations wouldn’t know about us by now

By Irene Klotz

updated 1/30/2012 8:40:46 PM ET

Mathematically speaking, E.T. would have found us by now — if he exists — so we’re being consciously avoided for some reason, a new study concludes.

“We’re either alone, or they’re out there and leave us alone,” mathematician Thomas Hair, with Florida Gulf Coast University in Fort Myers, told Discovery News.

Hair, who presented his research at the Mathematical Association of America in Boston earlier this month, based his approximation of what he considered to be extremely conservative estimates for how long it would take a society to muster up the resources and technological know-how to leave its home world and travel to another star.

Even at the relatively sedate pace of 1 percent of light-speed, the aliens would arrive at their nearest neighbor star in about 500 years. (Light travels at about 186,000 miles per second.)

Figure another 500 years to build new ships, set out again, and so on and so on, and the calculations show that civilizations starting out from the oldest stars in our galaxy would have had epochs of time to reach us by now. So where are they?

Full article here:

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/46197372/ns/technology_and_science-space/#.TygRr4Evjt0

Denver said on January 31, 2012 at 11:53:

“Imagine Genghis Khan with an anti-matter drive.”

Would a dictatorial or totalitarian regime also support a culture of people who could think freely enough to produce such technological wonders as an interstellar propulsion drive?

Perhaps by force. In the Soviet Union, Beria threatened those who built their nuclear bombs that if they didn’t get the job done, they would be taking an extended vacation in Eastern Siberia, or worse.

I know this is thinking like a human and a different species might be able to be both very controlling and still capable of creativity at least for its own means if nothing else (aka religion). However, when it comes to interstellar travel, I would think that while a totalitarian species might like to spread itself out, they may not like having members outside of its immediate grasp, as would happen with a galactic-spanning society. This assumes that some form of FTL travel and communication is not in place.

imagine our Pre Cooke Hawaiian island king showing up in modern New York and announcing he is ready to proclaim a fair law. As Mr Sims implies, we can colonize a mars even if it has microbial life. that is because we can only set the rules if we are the dominant culture. The other two cases are 1) we are new kids on the block in which case we can Study the real system, as it exists, laws or no laws, or 2) the distance and difficulties of contact makes only communications possible and makes physical visits seem pointless. since the chances of us stumbling upon a sentient species less advanced than us is Much less than finding an advanced culture, We will NOT get to set the rules, at least for the foreseeable future. Any advanced culture will know we are here or are coming. we may start finding or being contacted by less advanced cultures AFTER we have been star faring for a while.. that is, if there are any cultures out there at all. by then we will know the correct protocol, and what is expected of us.

I think the problem of harmful interference with an alien civilization is very unlikely to arise at all. As noted, the likelihood of encountering a civilization on roughly the same level of development as we are is very slim. But what does it mean “roughly the same level”? Some 10 years difference? 100? 1000? Finding a civilization that is within 100,000 years of ours seems to be essentially impossible. On a cosmic scale we would be very lucky if they are mere few millions of years ahead or behind us. And contaminating a 2 mln years older civilization is obviously not an issue, while those 2 mln years behind wouldn’t even have a coherent civilization as such to talk about – just scattered tribes without so much as an alphabet.

That being said, in case we do find some civilization resembling, say, our present level of development I don’t think it would make sense to stay away and not initiate a contact.

First, when we ponder morality of such an interference, I think we should look at the bigger picture: not simply they and us, but they and all other civilizations nearby, ourselves including, on one hand and their solitary past versus social future on the other. It is clear that if not by us, if not at the time, then by somebody other, at some other time they will be contacted. And since that moment they will always live with the knowledge of not being alone. Their life will be changed once and for all, changed to the more mature and realistic state. What is the point of deliberately keeping them ignorant or delusional or naive about the state of the things around them? What is the point of keeping them in a state that is going to be left behind anyway? They won’t think good of us when they finally find out. Staying away simply doesn’t seem to be too ethical.

Second, the argument that first we should wait until they reach certain level of development always seems to omit the fact that in the meantime we, the waiting party, won’t be standing still in our development either. And the pace of our progress is most likely to be much faster than that of theirs. It is almost like waiting until a present day tribe on some deserted Pacific island will learn how to build ocean-going vessels and come to us to initiate a contact. By the time they do that we may well leave the earth and live in space. In short, while we wait we ourselves change as well. We can’t say ‘When you’ll learn how to reach another star you’ll be more like us, closer to us, and then we’ll talk’ because in fact the opposite is true: by then we will be farther apart than ever. Waiting makes no sense.

Anthropocentrism distorts our view, but I wonder how a different strains of it might slightly alter our perspective.

Most animal genera contain several members, and ours only emptied very recently. The most prominent other species in ours was the Neanderthal, and had they survived till present things might look very different. It is a law of ecology that two species can’t occupy the same niche, so we would have had to each specialise and become part of an integrated whole – there is no chance that one species simply uplifted the other and maintained this through a tumultuous 10,000 years of civilisation. Under those circumstances we would not necessarily be inclined to believe in an equality between sentient species. We would be inclined to believe that they can be useful to each other, and that it is a moral imperative that they integrate into each others societies to gain maximum benefit (unlike the PD).

Another thing that might change our perspective is if it turned out that we were not the most intelligent species on Earth. I believe that the sperm whale is the only such candidate that can’t yet be said to have been shown to be unlikely to fill that role. If they are much more intelligent than us, would we still believe that ETIs would leave us peace. How bad would it be if they gave us that bit of information earlier? And just because it disturbed one technological society, and helped a species that wasn’t a member of one, why should we label such actions as immoral (as the above article seems to do).

ljk January 31, 2012 at 14:54

Denver said on January 31, 2012 at 11:53:

“Imagine Genghis Khan with an anti-matter drive.”

Would a dictatorial or totalitarian regime also support a culture of people who could think freely enough to produce such technological wonders as an interstellar propulsion drive?

A nondemokratic regime or society , like china , might have certain problems with the freedom of thought . On the other hand ,it might be capable of investing a much larger fraction of its resources into a relatively unpopular spaceproject , if this can be incorporated into the oficial ideology…

Who build the Pyramids ? They probably didnt wote for the democrats !

@ljk

Would a dictatorial or totalitarian regime also support a culture of people who could think freely enough to produce such technological wonders as an interstellar propulsion drive?

I find this a bit too narrow minded. The pace with which tech is developed is not dependent on the system in place. The Renascence, the Roman Empire, Greek, Egyptian, Arabian, Chinese and so on and so on. Some of the greatest thinkers and inventions were made during those periods.

“Who build the Pyramids ? They probably didnt wote for the democrats !”*

Actually everyone knows the Greys built the Pyramids.

So that future generations of our civilization would think we and our ancestors were stupid!

Maybe a prime directive should specify: “No practical joking at cultural expense.”

*The building of the Pyramids is a complex subject , thought to probably have been built by paid workers as ‘off season’ work they were glad to get.

Regarding the discussion around if we (or whoever) should or should not make contact with a less advanced civilisation. We can only speak really from human history, but the precedents are not promising. In human cultures contact between signficantly different cultures has tended to lead to ‘culture shock’ and severe damage to the less advanced society.

Even if the initial gap is less significant, very rapid technological and social change can be extremely destabilising (e.g. Iran pre 1979, Russia pre 1917 – although obviously these situations involved many factors).

Combine these considerations with the anthropocentric basis of sovereignty, religions and indeed most other human institutions and ‘contact’ would almost certainly be a total disaster for humanity in the short to medium term – on the assumption, as one CIA (or DIA – can’t remember exactly who wrote this) put it..’if they discover you it is a useful rule of thumb that’they’ are your technological superiors’. (That may not be exact word for word, as this if from memory). At the moment we aren’t in a position to do the discovering.

So thank goodness for the ‘great silence’ – either we are unbelievably lucky and will be the first advanced civilisation out there in due course, or we are incredibly lucky that ‘they’ are allowing us to manage our own development in our own way and at our own pace.

As an added thought – the relative gap betweeen advanced and emerging civilisations may not always remain as there appear to be fundamental limits regarding energy conversion from matter, information content per unit vulume etc. There may be a ‘step change’ from primitive to advanced, which we are currently going through, with progress eventuall levelling off as ultimate limits are approached?

@tesh

“I find this a bit too narrow minded. The pace with which tech is developed is not dependent on the system in place. The Renascence, the Roman Empire, Greek, Egyptian, Arabian, Chinese and so on and so on. Some of the greatest thinkers and inventions were made during those periods.”

Romans, Greeks – they used logic and made mistakes.

Why didn’t they do experimments (the few exceptions notwithstanding)? Because the dominant view in sclavagist societies was that manual labor was for slaves or peasants – not for intellectuals.

Arabians – they maintaned the ancient knowledge, but had very few original thinkers, they added little to said knowledge.

Chinese – they stagnated, did not develop a scientific revolution, falling behind Europe.

Renaissance – the ancient knowledge was rediscovered – and much enriched during the scientific revolution – in Europe.

The scientific development went hand in hand with the development of political systems based on ideeas centered around giving freedoms/rights to the people.

tesh, just because an ideea is not ‘politically correct’ by your standards does not mean it is not correct or that it is “narrow minded”.

@Avatar2.0

“Romans, Greeks – they used logic and made mistakes.”

I know of few Greek or Roman politicians and/or ruling class who used logic , ever.

(Actually it’s still true!)

“[Democritus] felt that poverty in a democracy was preferable to wealth in a tyranny.” – Carl Sagan on the ancient Greek natural philosopher who came up with the idea of atoms, Cosmos, Chapter 7, “The Backbone of Night”

Rodenberry invented the Prime Directive for dramatic reasons, in every story thereafter where it came up it was violated. He back-justified it as a super-tenth Amendment (The Federation will not interfere in local affairs. Anywhere.) , making the Federation actually a Confederation.

Don’t put much weight on Star Trek’s Prime Directive, but the question it nominally addresses is worthy of contemplation.

“Would a dictatorial or totalitarian regime also support a culture of people who could think freely enough to produce such technological wonders as an interstellar propulsion drive?”

The birth of space age technology occurred in Germany under the Hitler regime.

Avatar’s point about human non-technological societies vs technological Western civ is explained in detail in the excellent Harvard historian Nial Ferguson’s “Civilization”. It could have been entirely possible for human existence to have run its course without technology. Although I personally believe that by now the tech meme has permeated most human cultures and will endure, that is an opinion, not a fact. And as to space exploration, very little of the public has any interest. Not what we expected circa the early 1960s.

@Avatar2.0

I did not mean “narrow minded” in the (non-?)politically correct sense. It was not meant as a put down. My point is that most progress is pretty much dependent on philanthropy. Market forces do not lead to breakthroughs or new inventions. It is the whim of a local (official – king/pope/imam or entity (charity/city/district/country)) that is willing to invest energy/goods/food/money in a sustained manner. This can be done within the frame work of a feudal, capitalist, religious, “communist” or any other system.

There will always be some that will be inclined to explore (or kill) and others that are willing to invest in the aforementioned.

When last I checked logic is still the favoured currency among scientists and mistakes are still made. Progress however is still slow and unpredictable…

Just to add to my previous bit, it is all very fine and good that someone invests in an idea or the pursuit of an idea, and that it succeeds is another matter, but the timing is critical. Whether an invention comes at a time when it is needed is critical. The basics of the atom bomb were around for at least a couple of decades before it came to realisation. Before anyone mentions it, don’t mention the war! The concept of a flying machine was around for hundreds of years.

Timing, along with investment, is everything – the system of governance/control, in place is irrelevant.

@Anthony:

What a wonderful idea to contemplate! At the pace at which things are changing these days, there is no question that there has to be a leveling off of some sort, measured on the scale of millions or billions of years. We can not possibly predict the nature of the “end state” of such leveling, but we can ask a few pertinent questions: 1) Will this end state include living descendents of ours (in the widest sense)? and 2) How radical a difference will there be between the inital and end states? 3) will this difference be locally confined, or will it be present across the entire galaxy?

@Bob

Very true, and a great answer to the question.

In an aside, I sometimes wonder how justified the reflexive “Thank God we won against Hitler” view of WWII really is. History is full of bad dictators who eventually went in disgrace without a ruinous defeat in war. Someone ought to write an alternate history where, soon after his victory over the allied forces, Hitler is forced to step down and executed for crimes against humanity. The military distances itself from the Nazi party, which falls in disgrace and is thoroughly eradicated. The now world-spanning German Reich including the former United States and Soviet Union is largely demilitarized for lack of an enemy and develops a vibrant consumer economy under democratic rule in a revival of the Weimar republic, with added elements of US federalism. It lasts for a thousand years….

Kidding, really :)

Bob said on February 1, 2012 at 13:10:

“Would a dictatorial or totalitarian regime also support a culture of people who could think freely enough to produce such technological wonders as an interstellar propulsion drive?”

The birth of space age technology occurred in Germany under the Hitler regime.

Von Braun was arrested by the Nazis when he suggested that the V-2 rocket program might be used for space exploration instead of bombing Europe. They only let him go when they realized how much they needed his expertise.

Hitler was not very impressed with the V-2s in any case, but then again a scientist and technologist he was not.

In addition, Robert H. Goddard thought that many of his rocket ideas were used by the Germans for the V-2s, which he became convinced of after studying a captured V-2.

Avatar2.0 said on February 1, 2012 at 9:09:

“Arabians – they maintaned the ancient knowledge, but had very few original thinkers, they added little to said knowledge.”

Not sure where you get your historical knowledge from, but even though it may be currently fashionable by Westerners to put down their culture, Arab scientists and mathematicians of ancient times did a lot for human knowledge. Much of it was ahead of Europe and they preserved a lot of ancient Greek and Roman writings that would have been lost forever otherwise.

Here is just a sample:

http://www.cosmosmagazine.com/news/3924/ancient-arabic-scientists

I won’t even chase down your comments on China’s achievements in science and technology, as anyone who is interested can look them up. Let us just say that had China been as aggressive in colonization as the Europeans became during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, the global map of human culture would look quite different now.

ljk

“Not sure where you get your historical knowledge from[…]”

From everal sources.

Try Nial Ferguson’s “Civilization” or similar works.

For a summary, you could even go to wikipedia/google:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_science_and_technology_in_China#Scientific_and_technological_stagnation

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_science_in_Islamic_countries#The_views_of_historians_and_scholars

How Would Humans Respond to First Contact from an Alien World?

by Nancy Atkinson on April 5, 2012

According to Star Trek lore, it is only 51 years until humans encounter their first contact with an alien species. In the movie “Star Trek: First Contact,” on April 5, 2063, Vulcans pay a visit to an Earth recovering from a war-torn period (see the movie clip below.) But will such a planet-wide, history-changing event ever really take place? If you are logical, like Spock and his Vulcan species, science points towards the inevitability of first contact.

This is according to journalist Marc Kaufman, who is a science writer for the Washington Post and author of the book “First Contact: Scientific Breakthroughs in the Hunt for life Beyond Earth.” He writes that from humanity’s point of view, first contact would be a “harbinger of a new frontier in a dramatically changed cosmos.”

What are some of the arguments for and against the likelihood of first contact ever taking place and what would the implications be?

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/94456/how-would-humans-respond-to-first-contact-from-an-alien-world/