Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Set Your Gyros for Mars: Giving a Second Chance to Conquest of Space

Larry Klaes began developing a following for his deep dives into science fiction cinema long ago on Centauri Dreams, through memorable looks at films like The Thing from Another World, Forbidden Planet and The Day the Earth Stood Still. Although he delves into recent films as well, Larry’s frequent focus on the 1950s always intrigues me, as he places these movies in the context of our developing, rapidly changing ideas about the spacefaring future. How did our views of space travel change over time as we went from Sputnik to Apollo, and where are they heading today? All of that is a subtext in today’s look at Conquest of Space, an odd and irritating take on interplanetary travel with an unusual pedigree and cultural echoes that persist.

by Larry Klaes

Imagine if the iconic ground (and space) breaking science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey, first released into theaters in early 1968, had actually been put together over one decade earlier – in the mid-1950s, to be more precise.

Now contemplate that film’s famous and brilliant producer, Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999), being continually badgered and overruled by Hollywood studio executives who – while being neither terribly aware of nor interested in the genre, to say nothing of science in general – want this pioneering cinematic work to follow the more standard action and melodrama formulas of the day to ensure a paying audience. To top it off, these same meddlers want to be stingy with the film’s budget, one which needs to be relatively robust in order to pull off the impressive sets and special effects planned for this production.

Had this speculative scenario on Hollywood tampering with 2001 succeeded in our reality, the results would probably have resembled Conquest of Space, a science fiction film which premiered in April of 1955, courtesy of legendary producer George Pal (1908-1980) and Paramount Pictures Corporation.

Inspired by a landmark 1949 book of the same title, Conquest of Space (or, for brevity, just Conquest) is not terribly well known or popular outside of space and science fiction aficionado circles today, unlike 2001 and other certain films of its genre. This list includes SF cinematic pieces released right around the same time as Conquest such as This Island Earth (1955) and Forbidden Planet (1956).

Why is this? Well, to sum it up in one review comment I read while conducting research for this essay, Conquest of Space is “a B-movie with A-movie values.”

Unlike the other films and documentaries I have reviewed and discussed in the past, Conquest is the first film in this collection I have not seen multiple times before now. This came about in no small part as Conquest is a flawed work when it comes to just about every aspect a film can possess. Conquest even has trouble falling neatly into the category of “so bad it is good” that is given much more easily to many low-grade science fiction and horror films of its era.

Producer Pal strove mightily to make a good film on the level of his earlier masterpiece, Destination Moon (1950), and his efforts do shine in certain places in Conquest. However, the aforementioned interference from Hollywood executives turned Conquest into an awkward hybrid that was neither cheesy enough to entertain audiences at a base level nor polished enough to influence most viewers in a positive direction towards supporting real space exploration.

When I did finally view Conquest over a decade ago now, there was little motivation beyond a combination of curiosity, being a fan of science fiction in its multiple forms, a deep interest in pre-Space Age depictions of humanity in the Final Frontier, and a sense of completion.

Well before the end credits appeared, I felt little compulsion to see Conquest again any time soon. I was less than enchanted with most of the characters, some of whom I came to actively dislike: This state was made even worse by the fact that no one in the film was meant to be an outright villain. Their dialogue often ranged from dull to awful to ridiculous. Most of the attempts at humor felt shoehorned at best, when not being downright juvenile. There was also an air of melancholy throughout Conquest that the makers seem to have mistaken for drama, which only increased as the plot went along. By the time Conquest approached its conclusion, I no more wanted to be on that deep space expedition than the men who did take that fictional journey.

My initial reactions to Conquest were mirrored by those who were its first audiences nearly seven decades ago: Film critics were not much enchanted by Conquest outside of its special effects. Initial box office returns were well under the film’s budget of 1.5 million U.S. dollars (over seventeen million in 2024 U.S. dollars), an unforgivable sin in Hollywood both then and now. All this and more are what kept Conquest from joining its more illustrious and popular fellow genre films in the higher echelons of the science fiction cinema pantheon.

In contrast, Pal’s cinematic classic from 1950, Destination Moon (DM), succeeded where Conquest did not, despite having its own fairly two-dimensional characters: They included a rather infamous stereotyped comic “relief” from Brooklyn, who was also there as an Everyman to answer the audience’s more scientific and technical questions.

Destination Moon had two things going in its favor, however: Most importantly, the film refused to compromise on its primary intention: To depict a crewed expedition to Earth’s natural satellite as realistically as possible for its day. In addition, DM arrived at a time and place where few science fiction films before it had presented space travel in such a manner: One classic exception was the German film Woman in the Moon by producer Fritz Lang (1890-1976), released in 1929. Among its multiple technical feats, Woman included the first depiction of a rocket launch countdown that had been added for dramatic effect.

Pal’s earlier creation also appeared years before the official start of the Space Age in an era where, despite the fact that both the United States and Soviet Union had been sending rockets into near space since the end of World War 2, most people considered the idea of putting humans on the Moon a distant – yet still exciting – fantasy.

By the time Conquest came along five years later, there had been numerous genre films with space missions as a main theme (although relatively few could claim to be very scientifically and technically plausible) released into theaters worldwide. The advent of actual space exploration seemed much closer than it did at the start of the 1950s, with both Cold War superpowers making serious claims of launching the first Earth orbiting satellites and even missions to the Moon just a few years into their future. As a result, Conquest had a lot more to live up to than its predecessor beyond just being about a manned rocketship voyage to another world.

For those who want to learn more about Destination Moon, check out this excellent essay authored by Albert A. Jackson here:

https://www.centauri-dreams.org/2020/06/12/destination-moon-a-70th-anniversary-appreciation/

Once More unto the Breach, Dear Friends…

Despite my less than enchanted first impressions of Conquest of Space, I felt compelled over time to see what diamonds might be buried in that film amongst all the cinematic dirt. After all, with Conquest, George Pal did attempt to make yet another good science fiction film based on realistic plans for both space vessels and expeditions. In addition, his track record of past excellent productions was certainly no fluke.

This time around, I learned among other things that Conquest may have had an important influence on 2001: A Space Odyssey, of all films. You will find a video that highlights where in Conquest that Kubrick may have been inspired for his own creation in the “References” section at the end of this essay.

This very deed alone is enough to give Conquest a second look. We will also examine what the film both did and did not do right as a learning exercise regarding filmmaking and human space exploration, as well as both a tribute and time capsule as a classic member of both early science fiction cinema and a promoter of our species’ real desire to reach into outer space.

A Distinguished Pedigree

Conquest of Space was the result of a growing interest in rocketry and space exploration begun earlier in the Twentieth Century. This fascination with reaching the vast realm beyond Earth only accelerated after the technological advancements and geopolitical changes spawned by World War 2.

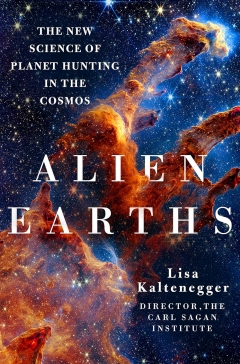

One of the results of this interest was a book, titled The Conquest of Space, authored by science writer and rocket pioneer Willy Ley (1906-1969) and illustrated by legendary space artist Chesley Bonestell (1888-1986). The book had no written story to speak of, but it did lay out in a blending of words and art various plans for how humanity could explore and settle the Sol system at a time (the early Cold War era) when only a relative handful of rockets had penetrated space for a mere matter of minutes.

FIGURE 1. Where it all began: The cover of the first edition of The Conquest of Space (1949), depicting an imagined manned landing on the Moon with an iconic silvery spire spaceship and jagged lunar mountains in the background.

Conquest is a beautiful book that impresses even in today’s world built upon decades of thousands of real satellites and space vessels across the void from Earth orbit to the interstellar realm. In the years just before the advent of the Space Age, this adept confluence of art and science was nothing less than stunning to those who read it. The artwork alone, created by an artist with exacting standards for scientific and technical realism, is enough to see why this book inspired Pal to want to turn it into a film and how it influenced others such as science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008), who would work on both the film and novel versions of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

COMMENT: There was an even earlier book of the same title authored and self-published in 1931 by David Lasser (1902-1996), who became both the founder and first president of the American Interplanetary Society, now known as the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA).

This Conquest of Space was the first English language book to describe spaceflight and rocketry in a straightforward way: Lasser’s work included the depiction a fictional Moon mission infused with contemporary scientific and technical information. Among those who considered this book to be a life and career turning point for them was author Clarke.

FYI: Conquest was brought back into print in 2002 thanks to Apogee Books. You may also find a fascinating interview with Lasser here:

The other key place where Pal et al borrowed spaceship designs and other ideas for the film Conquest was a series of articles published between 1952 and 1954 in Collier’s, a popular magazine of the day. The publication had hosted the First Symposium on Space Flight on October 12, 1951, at the Hayden Planetarium in New York City and shared the fascinating results in its pages over a two-year period.

This influence is apparent in the very first issue reproduced here, where the opening of Conquest mirrors the artist’s depiction of a giant wheeled space station and winged rocket ship in Earth orbit:

http://dreamsofspace.blogspot.com/2012/03/colliers-march-22-1952-man-will-conquer.html

You can review a complete list of each Collier’s article and their issues here:

The Collier’s magazine articles were later collected, revised, and expanded into three books published by The Viking Press of New York, all of which I highly recommend

acquiring, if possible:

• Across the Space Frontier (1952)

• Conquest of the Moon (1953)

• The Exploration of Mars (1956)

The very same articles were also big influences for a series of complimentary television episodes for Walt Disney as part of their Tomorrowland setting. The first two episodes, “Man in Space” and “Man and the Moon”, premiered in 1955, with the former program hitting the airwaves just one month before the arrival of Conquest in the cinemas. The third installment, “Mars and Beyond”, debuted just two months after the beginning of the official Space Age with the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957.

The Disneyland series did utilize stories to showcase how contemporary experts envisioned space expeditions into Earth orbit and beyond to the Moon and Mars. However, they mainly existed to describe the mission and technical details of these journeys; there was no real character development to speak of.

I was particularly struck by one scene in “Man and the Moon” where two orbiting astronauts discover what looks like the remains of an artificial structure on the surface of the lunar farside. However, neither the explorers nor the episode narrator make any comments or even visibly react on what should be a startling find. The incident is never brought up again.

Thankfully for real science and humanity this was just a fictional event, as I cannot imagine even the most stoic astronaut or scientist not responding in some form to what appeared to be an alien artifact on our neighboring world. Had such an object been found in Conquest, one could at least be guaranteed that our characters would most definitely react to it, and rather loudly at that.

OBSERVATION: I get that Disney wanted to present a sober and serious program on a subject that the general public and even some professionals of the day had trouble taking as near-future reality, but for astronauts to witness something on the Moon likely made by non-human beings and do apparently nothing about it is in certain respects worse than turning the spectacle into some kind of overblown space fantasy. When the Apollo astronauts were both circling and walking upon our celestial companion just over one decade later, they were often heard exclaiming at all sorts of natural views there, and the majority of these men were trained test and combat pilots not usually given to emotional outbursts, at least while on the job.

Although never official, Conquest of Space could also be seen as a sequel of sorts to the films that George Pal made for Paramount Pictures Corporation, starting with Destination Moon in 1950, a painstakingly scientific and technically plausible depiction of a manned lunar expedition using a nuclear-powered rocketship christened Luna, appropriately enough.

Producer Pal then followed up this cinematic pioneering triumph with two different takes on space travel: In 1951’s When Worlds Collide, a vessel not too different in the V-2 rocket style design from Luna – only much larger and launched from a long rail going up a mountainside – is used to save a rather small slice of the human race when a rogue exoplanet collides with Earth and obliterates our globe.

COMMENT: The failure of Conquest at the box office and the difficulties in making that film kept Pal from his plans to produce a sequel to When Worlds Collide, which would very likely have been titled After Worlds Collide and based on the 1934 novel co-written by Edwin Balmer and Philip Wylie.

Two years later, Pal released The War of the Worlds, his take on H. G. Wells (1866-1946) famous science fiction novel first put together in print in 1897. This time the spaceships came from another planet, an ecologically ancient and dying Mars, where they were built and utilized by its natives not to explore the Sol system but rather to attempt an invasion and conquest of Earth to make into their new home.

COMMENT: Chesley Bonestell contributed his talent to both When Worlds Collide and The War of the Worlds: He made a wonderful matte painting of an alien landscape in the former film and gave us an exquisite visual tour of all the major members of our planetary neighborhood in the latter – with the notable exception of Venus, which was still such a mysterious world in the early 1950s due to its relentlessly thick blanket of globe-spanning clouds.

Before the era of directly examining other worlds with space probes, many scientists considered it possible that Venus was conducive to life, as that planet was nearly as large as Earth and covered in those obscuring clouds, indicating a substantial atmosphere. This is why, in the original novel, Wells had his Martians attempt to colonize the second world from Sol after their ultimate defeat on Earth, where their invading forces had been “slain by the putrefactive and disease bacteria against which their systems were unprepared; slain as the red weed was being slain; slain, after all man’s devices had failed, by the humblest things that God, in His wisdom, has put upon this Earth.”

In his other contemporary astronomical works, Bonestell painted Venus as both a roasting desert and a wet jungle full of dinosaur-type creatures: Two contrasting venues that were considered scientifically plausible by various astronomers of the day. Contemporary scientists even played with the possibilities of Venus being globally covered by vast seas of water, oil, and even seltzer!

When the first attempts to reach the surface of Venus were being made by the Soviet space program in the 1960s, their spherical landers were designed to float in a liquid medium. They stuck with this plan even after the American flyby probe Mariner 2 had determined in December of 1962 that the global surface temperature of the second planet averaged over 800 degrees Fahrenheit, or 427 degrees Celsius, far above the boiling point of water. Later missions would revise that temperature to be over one hundred degrees higher. Recent studies show that Venus may once indeed have had oceans of liquid H2O, but they evaporated eons ago.

You may watch the title sequence opening to The War of the Worlds here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AZQTKs2YDPc

With these film successes, plus the multiple events that placed humanity just a few years from reaching space in a more permanent manner, Pal felt it was time to expand upon what he started with Destination Moon and create an even grander reality-based space adventure, with those fantastic recent books and periodicals serving as the ideal templates for his vision. They just needed a story with fleshed-out characters to tie all those amazing visuals and technological details together to make a popular level film.

Thus, the cinematic Conquest of Space was born.

The Day After Tomorrow… or Maybe the Week After Next

FIGURE 2. The theatrical poster for Conquest of Space, declaring how what we see in this film will happen “in your lifetime!”

With the primary introductions and background information now presented, it is time to look and comment upon Conquest of Space in depth. Naturally, there will be major plot spoilers throughout our journey together, so you may want to view the film before continuing with this essay. If you have not yet seen Conquest, or you have but still desire a refresher, one way you can view the film is through the appropriate links in the “References” section after the main body of this essay.

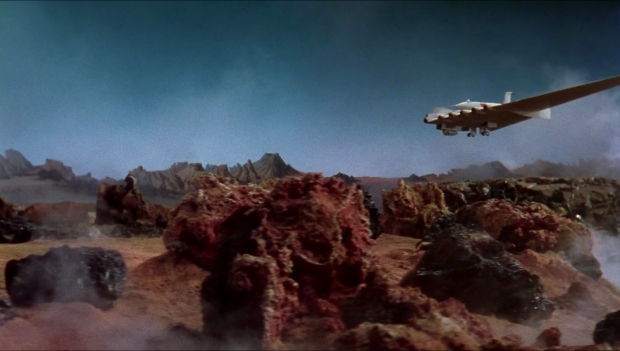

Conquest is said to take place sometime in the then-future decade of the 1980s, possibly the exact year of 1980. However, outside of some impressive space technologies and multiple large viewscreens, we residents of the Twenty-First Century might be forgiven while watching this film for thinking the story occurs in the 1950s or perhaps even the 1940s, judging by the World War 2 era stereotypes, styles, and mannerisms of the characters and the story elements we will encounter.

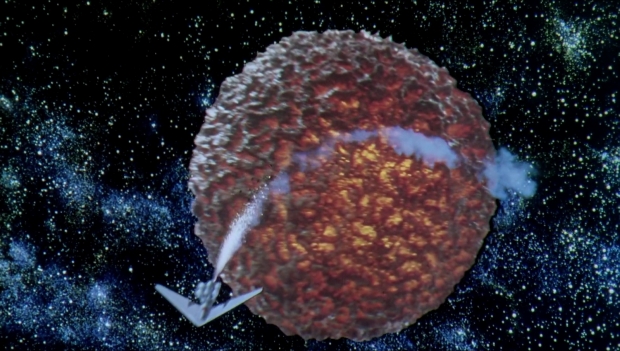

Our film opens in outer space over the predominantly blue curvature of the planet Earth. Two clearly artificial structures appear above our cosmic home in the center of this scene: On the left is a large, wide space vessel resembling a fixed-wing aircraft with an attached rocketship and four spherical fuel tanks in the center of this configuration. To our right is a gleaming white and spinning disc-shaped space station. Much further in the background shine the stars of the Milky Way galaxy, specifically those belonging to our section of this immense stellar island, the Orion Arm. This vast river of suns seems to be beckoning to those intelligent and capable enough to reach out for them.

We barely have time to grasp all this when the disembodied voice of a male narrator deeply intones when and where we are in literal time and space…

“This a story of tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow, when men have built a station in space, constructed in the form of a great wheel and set a thousand miles out from the Earth, fixed by gravity and turning about the world every two hours, serving a double purpose: An observation post in the heavens and a place where a spaceship can be assembled and then launched to explore other planets and the vast Universe itself, in the last and greatest adventure of mankind, a plunge toward the… conquest of space!”

Cue very dramatic orchestral music as the rocketship noisily blasts off into the Final Frontier in a cluster of smoke, flames, and sparks. The film title appears in large golden block letters, followed by the opening credits – none of which list any of the actors and the characters they play, which is unusual for a film of its day: One possible reason for this is that there were no big name actors in Conquest who would be considered box office draws.

To see the opening of Conquest for yourself, go here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pWINrpzDQCY

Let us step back for a moment to take a closer look at the introduction to our film:

As the camera closes in first on the rotating space station, we are told that this “great wheel” built by men is “set a thousand miles out from the Earth,” where it orbits our planet every two hours.

Just a few years after Conquest arrived on the scene, in 1958 to exact, scientists would discover that – thanks to the scientific instruments aboard the first successful American satellite Explorer 1 – the planet they reside upon is girdled by two main zones of energetic charged particles known as the Van Allen Radiation Belts. Trapped by our planet’s magnetosphere, these fields of radiation, which extend from 400 to 36,040 miles (640 to 58,000 kilometers) above our globe, can be intense enough to damage satellite equipment and cause physical harm to humans who linger there for long periods of time. Unless this cinematic space station has extra layers of shielding, the “great wheel” would have to be relocated much closer to Earth to avoid these belts and give its occupants further protection from solar flares and cosmic rays.

The narrator then explains that the space station has a “double purpose” for being up there: As an “observation post in the heavens” to look both down at Earth and up into the rest of the Universe and as an assembly yard for building vessels that can be launched towards other worlds in our Sol system and some day beyond into the rest of the Milky Way galaxy. This latter plan is emphasized by the image of the winged spaceship dominating the screen.

Early plans for space stations were epitomized by the one we see in Conquest: The spinning wheel design meant to provide a form of gravity for its human crew using centrifugal force; a “high ground” platform to monitor important activities on Earth such as global weather patterns and military actions; and finally, as a place to put together large spacecraft (shipped up in pieces from our world below via multiple rocket transports) to be sent virtually anywhere humanity wanted to explore in our planetary system.

Conducting meteorology from space and watching the actions of a nation’s rivals from Earth orbit have indeed become among the biggest reasons for operating in near space, along with international communications – although these functions are most often conducted by artificial satellites located in geosynchronous orbits averaging 22,236 miles (35,786 kilometers) in altitude, where they can match the rotation speed of our planet and thus seem to hover over one particular region.

While space engineers and scientists of the 1950s knew the first vessels to be sent into Earth orbit would be automated satellites, the technologies of the day were often considered still too bulky and cumbersome to provide more intricate work such as spying on other nations from hundreds of miles up. This is why the wheeled space station concept manned by dozens of personnel – and dominated by members of the military – watching over our world for any suspicious rival activities, up to and including surprise missile launches, were considered the best option for keeping the Cold War from turning into a hot one. At the very least, it was hoped that if the “other side” decided to start World War 3, we would not be caught off guard and could retaliate in kind, thanks to our ever-vigilant eyes in the sky.

COMMENT: In 1949, German rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun (1912–1977), whose ideas for future space utilization and exploration were among the major influences of the space vessels and plans for Conquest, wrote a science fiction novel he titled Marsprojekt, or The Mars Project in English. Von Braun created a story of the first manned expedition to the Red Planet set in the 1980s to explain in a popular manner how he envisioned such a voyage might come about.

According to the background history of this tale, we learn that humanity underwent a nuclear conflict in the 1970s which was won by the West when they used an orbiting space station named Lunetta to fire nuclear missiles upon the Soviet Union. Not long after this war, which established the United States of Earth as the dominating global power, a large reflector telescope on Lunetta determines that the famous Canals of Mars are real structures built by technologically advanced Martians and not mere natural features or optical illusions as some terrestrial astronomers had claimed. An expedition is funded and constructed at the space station, which includes three winged vessels designed to land on the fourth world from Sol. One of the mission goals includes determining if the Mars natives are either friendly or hostile.

In our history, the United States Air Force (USAF) seriously considered using an occupied space station to conduct reconnaissance operations from orbit: The effort was called the Manned Orbiting Laboratory, or MOL for short. The project got as far as the successful launching of an unoccupied station mockup in late 1966, but it was eventually determined that uncrewed satellites could do the spying much better and far more cheaply in comparison. MOL was cancelled abruptly in June of 1969.

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) did build and launch two working space stations under their Almaz (Diamond) reconnaissance program in the early 1970s. Publicly labeled Salyut 3 and Salyut 5, the cosmonauts aboard these cylindrical stations did perform some clandestine spy work, but even their officials concluded that robot spysats were just more efficient for this task.

That satellite telescopes can see the heavens much more clearly than their ground-based counterparts buried under those turbulent and cloud-strewn layers of terrestrial atmosphere has been known for a long time. The general public is well familiar with the astronomical results beamed back by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and most recently by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), revolutionizing our knowledge of the Universe in the optical and infrared spectrums, respectively.

Crewed space stations have also gotten in on the astronomical act: To cite just two historical examples, in the early 1970s, the United States Skylab astronauts observed our yellow dwarf star Sol in unprecedented detail thanks to their station’s Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM). They also monitored and recorded the activities on Comet Kohoutek: Their vantage point allowed the astronauts to witness this ancient ice ball when it neared Sol that astronomers stuck on Earth could not.

As for building and launching missions to other worlds, no real space station has yet been a part of such a major undertaking, unless you want to count the fair number of CubeSats that have been ejected from the International Space Station (ISS) to circle Earth for a wide variety of purposes.

Nevertheless, as global space utilization and industrialization continue to grow, there will one day be the equivalent of drydocks in Earth orbit. Space vessels will be built in sections on our planet and other places such as the Moon or a planetoid fitted for this task and then shipped via rocket to these special stations where teams will assemble them for missions all over the Sol system, just as Conquest of Space predicted. For as science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) and several other prominent folks have said: “Once you get to Earth orbit, you’re halfway to anywhere in the Solar System!”

For more on this quote and concept, see here:

The Wheel

Once the opening film credits of Conquest end, we move back to the winged rocketship and space station. As the camera slowly closes in on the rotating station, the wordless scene is accompanied by ethereal background music that reminds me of the “Neptune” segment from The Planets, composed by Gustav Holst (1874-1934) between the years 1914 and 1917.

COMMENT: I would be surprised if this piece was not influenced by Holst’s work. If you would like to compare what is presented here in Conquest (and will be again later in the film almost every time the ship is shown moving through deep space) with Holst’s “Neptune”, visit here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9BAFirzGlFk

We fade into the station, where we see two men in beige uniforms working at some controls. In the background along a wall are rows of instruments resembling face clocks with hands.

“Rocket coming up, sir,” one of the men in beige, a Corporal, relays to his commander, who suddenly appears in the frame with another officer, both of whom are wearing blue uniforms and much darker color caps. They all stare down together at what is revealed to be a small viewscreen, where a rocketship spewing white exhaust is shown heading towards them, with Earth in the background filling the screen.

“It’s the transport, right on schedule, eh, Captain?” declares the Corporal.

“No, sir, they’re late,” contradicts the Captain. “A minute and 33 seconds.”

“It’s a minute and 34 seconds, Captain,” corrects the other officer, a Colonel. “It’s not important, of course, but it could be. In celestial navigation, one second can be the difference between life and death.”

COMMENT: The Colonel is of course quite correct, although one might initially be wondering why he would need to tell this to a fellow officer working aboard the space station. One possible answer is that the Colonel considered this a teachable moment and did not want to pass it up. Another answer is that the comment was dually meant for the film’s contemporary audience, who were not generally expected to know much about celestial mechanics and rocketry. This will certainly not be the last time we witness a character committing to a bit of exposition for these very reasons.

Still looking down at the screen, the Corporal excitedly exclaims: “Gee, I hope they don’t forget to bring up the ice cream this time!”

Smiling at this seemingly innocent spoken desire, the Corporal turns to the two officers expecting them to agree with him, only to see the Colonel staring at him sternly. Realizing he has made a verbal slip, the Corporal suddenly stands stiffly at attention and partially faces away from the two officers.

“I thought I issued an order to the effect that food was never to be a subject of conversation on the Wheel!” the Colonel barks at the unfortunate man.

“I’m sorry, sir, I forgot.”

“There are some men aboard who are not permitted to enjoy the food that you eat, Corporal, and unless you’re anxious to share their diet, I’d advise you not to forget again.”

The Corporal assures his senior officer that he will definitely remember this particular “lesson.” The two officers walk off and head towards a nearby hatch. As the Captain opens the heavy metal door, the Colonel gives the Corporal one final warning look before the two officers depart the control room.

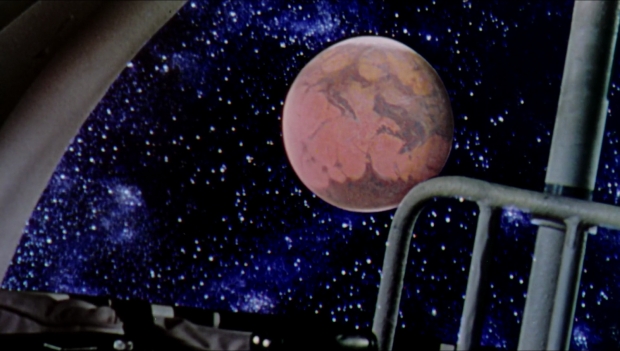

The two men enter another section of the Wheel. The Colonel, whose name is Samuel T. Merritt, activates some switches and dials on a panel labeled Observation Screen. A magnified image of the full phase Moon appears on the wall before them, with the Milky Way somehow showing behind the large bright sphere. Samuel and the Captain, who is in fact his son, Barney Merritt, meaningfully stand in front of the Moon from our perspective.

COMMENT: Although we never actually see it, nor is it even mentioned specifically in the film, this magnified display of Earth’s only natural satellite is evidence that the Conquest space station has a telescope designated for astronomical work, an “observation post in the heavens” as the narrator stated at the opening to this film. This scientific instrument was always a part of the orbital station design as envisioned by Wernher von Braun and others. The onboard telescope is meant for examining the other worlds of our Sol system up close without atmospheric interference as a prelude to their exploration via spaceship.

Looking at the projected lunar image, Samuel makes some wistful commentary to his son which also reveals the purpose of that winged spaceship parked near the station.

“The Moon, Barney. A few days, a month, and we’ll be on it,” declares Sam, who is in the process of retrieving a pack of cigarettes from his lower jacket pocket with his right hand and placing one of them in his other hand.

Barney, however, has other thoughts on his mind than exploring Earth’s celestial companion.

“Do you realize, sir, that I’ve been up here a full year without any leave?”

“There are several of us in the same boat, Barney,” reminds his father.

Barney protests that he had “only been married for three and a half months” before being essentially commandeered to serve on the space station.

“I’m sure Linda will understand,” Samuel responds about his son’s spouse. “She’s a sensible girl. After all, when a girl marries a soldier…”

“Soldier!” Barney retorts, strongly enough that his father stops placing that lone cigarette in his mouth in mid movement. “Ghost, you mean. A robot spinning around the world every two hours on a tin doughnut! That’s what you’ve been to Mother for three years – and what I’m becoming to my wife!”

Samuel shouts out his son’s name in a shocked and offended reply, but Barney continues his rant.

“I’m sorry, sir. You built the Wheel, and you’re proud of it. You’ve got every right to be, but… well, why me? We were happy down there. A little cottage right on the base, she was just beginning to furnish it, and you yank me out of it.”

“You belong here, Barney. You’re my son. Space is your heritage.”

Samuel’s offspring is neither impressed nor deterred by his father’s heartfelt declarations.

“I formally request, sir, that inasmuch as service on the Wheel is voluntary and I have never been accorded the privilege of volunteering, that I be granted permission to return to Earth on the transport rocket.”

At that moment, another man in a beige uniform enters the section with some news for Samuel.

“Colonel, sir, there’s a storm building up in the Pacific. A real lulu. Might be a hurricane.”

“Chart it and notify all weather stations likely to be affected,” orders Samuel.

“Yes, sir,” is the beige man’s succinct reply before he heads off to do as he is told.

COMMENT: In addition to creating a dramatic pause, this moment symbolizes what the public would learn just a few years hence: That observing Earth’s weather from space will become a huge boon to the field of meteorology, especially in the detection and monitoring of hurricanes and other cyclonic storms. Thematically, this moment can also be seen as an allegorical point that the story is about to become stormier for the characters – which it will.

Samuel walks over to the viewscreen and shuts it off. The Moon disappears, replaced with blackness.

“Permission denied, Captain,” is the Colonel’s blunt response.

With obvious frustration and anger, Barney quickly storms out of the observation section without saying another word. The father merely watches after his son while lighting up his cigarette and finally inserting it into his mouth.

COMMENT: This space station must have a very efficient air filtration system to allow smoking in such a relatively confining place where one cannot simply open a window if they want fresh air or step outside unfettered. This is also another cultural clue that it may be circa 1980 in the film, but circa 1955 in most other respects.

To be fair, in the real year of 1980 there was still a lot of public smoking going on, even though the serious health dangers to inhaling carcinogens had become widely known in the previous two decades.

In the book Across the Space Frontier (1952), written by Joseph Kaplan, Wernher von Braun, et al, they had this to say about crewmen smoking onboard their space station concept, which was the template for the Wheel in Conquest:

“Even smoking will probably be strictly rationed, partly to save oxygen and partly to avoid overloading the capacity of the air-conditioning unit.”

IRONIC SIDE NOTE: During the first press conference for the seven chosen astronauts of Project Mercury held in April of 1959, one of the very first questions from the media asked of our pioneering “star sailors” was how many of the men smoked and could they handle going without lighting up during their space missions? Three of the astronauts acknowledged that they smoked on a regular basis, but all of them said they could go without smoking during those times. Considering just how cramped the Mercury spacecraft interior was, there would not have been much choice for them in any case.

Space Fatigue

Our scene changes back into space. With that same ethereal music, this time we head towards the winged spaceship parked some distance from the rotating space station.

Inside the spacecraft, we see four men enclosed in white spacesuits preparing the ship for its historic journey. One might think the conversations between these men working on a sophisticated vessel meant to land humans on the Moon would be quite technical in nature, perhaps even introspective and philosophical. However, as we listen in, we discover that their exchanges could be happening just about anywhere, such as a loading dock…

“Somehow or another, I kind of hate to see this job get finished,” says one man with a distinctly Brooklyn accent. “It’s like my cousin Seymour. He’s a plastic surgeon. He built a face for an ugly dame once, which turned out to be so beautiful, he fell in love with her! So off she went with the garbage collector!”

“You afraid this beautiful ship will go off without you, Jackie?” replies another suited man who we will learn is Sergeant Imoto, a native of Japan.

“Precisely and definitely the opposite,” retorts Jackie, who is also known as Sergeant Siegle.

The third Sergeant in the room, Roy Cooper, shares his feelings on the topic of conversation.

“Well, frankly, I’m… I’m frightened of going, but… I’m more frightened of being left behind.”

“For what you scared?” asks the fourth member of this group, Pete Donkersgoed, as he emerges from an opened hatch in the deck. “We build this ship, so we fly it.”

“And so we get to the Moon,” Siegle chimes in with an expression of annoyance. “Who’s gonna guarantee we ever get back? I’m with Pete.”

Sergeant Siegle then offers more of his thoughts about the lunar mission to the group, continuing to contradict himself in the process.

“For a fat, solid year, I been eating birdseed out of this goofy sombrero with no squawk!” declares Siegle, commenting on something that will only make complete sense to the audience later in this story. “Now, let some other heroes take it from here. This little guinea pig ain’t going on no more joy-hops for the great Colonel Merritt! And if old Space Happy thinks otherwise… he can take his ship and…”

“And what, Sergeant Siegle?” demands old Space Happy – I mean Colonel Samuel T. Merritt – who has been surreptitiously listening in on their conversations from the Wheel the entire time. Jackie Siegle looks around in surprise, embarrassment, and fear at the voice coming over the radio.

Jackie makes a weak attempt to disguise his voice to his superior officer.

“Sergeant Siegle just left, sir!”

Satisfied that he has sufficiently intimidated his charges into line and keeping their thoughts about the mission to themselves, Colonel Merritt turns away from the radio panel to other business in the control room of the Wheel.

Meanwhile, Roy Cooper is busy connecting a live cable to an open panel full of electronics. Suddenly there is a bright spark followed by a series of loud electrical discharges that panic Roy into immobility.

“Roy!” cries Imoto. “Secure that cable!”

“I… I… can’t… move a finger,” Roy replies haltingly, his eyes wide and his suited body plastered flat against the nearby wall.

Imoto and Siegle rush in to grab the loose cable and prevent a potential fire or worse. Once they have the situation under control, the two sergeants turn their attention and concern to their colleague.

“Are you hurt?” asks Imoto.

“No, but I…” starts Roy. Imoto presses him further.

“What is the matter with you?”

“I don’t know,” Roy answers. “I’m… I’m… paralyzed.”

“Let’s get him back to the Wheel!” shouts Siegle. “Taxi!”

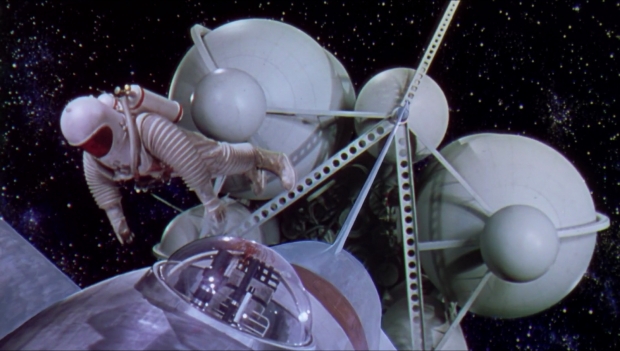

The taxi Sergeant Siegle calls for is no four-wheeled yellow cab from Brooklyn, but a small sled-like craft piloted by a single astronaut that we soon see approaching the winged spaceship from the Wheel. Roy and his fellow crewmembers are waiting at an open hatch in the side of the rocket.

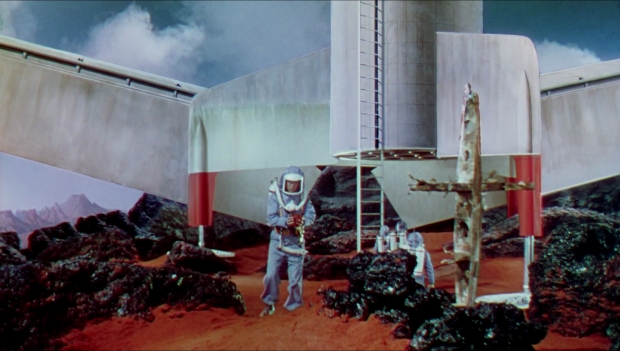

FIGURE 3. Here comes the space taxi Sergeant Siegle called for to get Roy Cooper back to the Wheel for medical attention. The other astronauts working on the spaceship will also ride back with Sergeant Cooper by being towed like water skiers. I guess that makes them space skiers, ay?

“We’ve got a sick man here!” Siegle barks to the taxi pilot over his suit radio, likely adding to Roy’s discomfort and embarrassment in the process. “Gotta get him back to the Wheel!”

They lay Roy face down across the back of the space taxi in a manner not unlike loading inanimate cargo. Then the three remaining crewmen grab on to towlines attached to the rear of the taxi.

“AII set. Shove off!”

The pilot fires a short burst from the taxi’s thrusters and the vessel moves away from the spaceship towards the space station, pulling along the three astronauts like water skiers – minus any water or skis.

COMMENT: It is a very good thing for the astronauts riding on those tow lines that the space taxi’s main stern thruster only produces short bursts of exhaust, or at least does in this case when it comes to bringing extra passengers along in this manner, because otherwise these men would be right in the line of the rocket’s fire! I also wonder why the taxi doesn’t have more room or at least a platform/gurney of some kind for carrying cargo or passengers, especially if a crewman requires medical attention? Perhaps there are other models of taxis for various functions at the space station and this was the one most immediately available due to the perceived urgency of the situation?

Back in the Wheel, in an area right outside the airlock, we see personnel dropping down their discarded spacesuits attached to a line from a wide tunnel overhead. The astronauts then follow their protective coverings using a tall black lattice structure as a ladder, where they subsequently pick up and carry off their suits to be stowed away in cage-like lockers.

Imoto and Roy Cooper are putting away their spacesuits in the same fashion. We become aware of an older, larger man in a beige uniform decorated with sergeant stripes standing next to the pair, his arms folded. He is carefully observing the activity around him with an expression that could be either one of concern or annoyance, or possibly both.

COMMENT: We the viewing audience will soon learn that this stern Irishman is called Sergeant Mahoney and he has been placed in charge of ensuring the well-being of the Moon mission crew – whether they actually like it or not.

“Are you feeling better, Roy?” Sergeant Imoto inquires of his friend and colleague.

“I’m all right, I guess,” Roy answers, not sounding entirely confident. “Yeah, I’m all right.”

Having been listening to their conversation, Mahoney doesn’t hesitate to cut in.

“Let’s have the straight of it,” Mahoney demands, without any social platitudes. “What’s wrong with the Iad? What’s the matter? You sick or something? You hurt some place?” Placing his arms akimbo, Mahoney almost gets into Roy’s face waiting for an answer.

“No, I… I just couldn’t move out there,” Roy tries to explain, “but… I’m all right.”

“You couldn’t move, you say? Why not?” Mahoney pushes even further into Roy’s personal space as the volume of his voice goes up.

“I don’t know, I… I just couldn’t.”

Just then Sergeant Siegle walks up from around one of the metal storage cages, coming to Roy’s defense.

“He’s all right, he told you. Leave him alone! It ain’t important!” declares the very person who only a short while earlier was shouting to everyone in range how Cooper was “a sick man.”

“You know the Colonel’s orders with you incubator babies,” Mahoney snaps back, just barely turning towards Siegle and then only for a moment. “Even a pimple is important. You bluebirds are my responsibility, and he’s reporting to the infirmary. Come on, lad, I’II take you meself.”

Without even asking cursory permission, Mahoney grabs Roy by the arm and starts escorting him away. Siegle makes a rude vocal noise mocking the gruff Sergeant, who pauses his steps and glowers for only a brief second before continuing with Roy to the infirmary.

Staring after the departing Cooper and Mahoney, Siegle comments to Imoto that “it’d be worth taking a trip to the Moon, just to get rid of that overgrown babysitter!”

COMMENT: Considering that the rocket crew had to radio the Wheel with an urgent need for a space taxi, which I presume included requiring a reason for that transportation, I am surprised that someone from the medical staff on the station wasn’t waiting for Roy at the airlock to escort him to the infirmary upon his arrival. Instead, there seemed to be no one in that section of the Wheel aware of what happened over on the spaceship, including the men’s “overgrown babysitter”, Sergeant Mahoney.

The scene fades to the station infirmary, where a doctor by the name of Major Kurt Elsbach is finishing his examination of Roy. In the same room with them is Colonel Sam Merritt and another doctor named Sergeant Andre Fodor, a native of Austria.

“What is it, sir?” Roy asks nervously. “I… I’m all right, aren’t I?”

The doctor assures Roy that he is fine, only adding that what happened to him on the spaceship was “nothing more serious than a momentary lapse of nerve function.”

Still anxious despite the doctor’s response, Roy walks up to the Colonel.

“You believe him, sir?” Roy asks the Colonel as to what the doctor had just said. “I mean, this couldn’t make any difference. It’s been a whole year, sir, and after all this time, I… I’d hate to wash out.”

The Colonel answers in a somewhat deflective manner.

“Well, I’d hate to lose you, Cooper.”

Roy thanks the Colonel and walks towards the hatch. Fodor opens the door for him, where he adds a friendly smile and a pat on the shoulder as reassurance to the man who exits.

Colonel Merritt walks up to the first doctor.

“Let’s have it, Kurt,” Merritt demands. “What’s really the matter with that boy?”

Before Doctor Kurt can comply, Fodor cuts in with his own unrequested response.

“Oh, Cooper’s in fine condition, sir,” Fodor interjects, clearly trying to defend his colleague and friend. “Why, you gave him a complete physical examination only three days ago, Major. A perfect score, remember? You don’t have to worry about that boy, sir, I assure you.”

“He was paralyzed out there, Sergeant,” Merritt responds matter-of-factly. “He couldn’t move. That’s something to worry about up here.”

Merritt quickly turns back to Doctor Elsbach to ask what is really going on with Roy.

“Somatic dysphasia,” the doctor replies, then explains his technical term: “Self-induced inability of the nerves to transmit brain messages. In your language, space fatigue.”

COMMENT 1: Now I am no Doctor of Medicine, but it would seem the Conquest writers created a new scientific term for what they are calling space fatigue. This makes sense, since these men live continuously in space in an artificial environment of a retro-future era unlike the one most Earth-based humans have known.

As an interesting side note: In the 1956 film Forbidden Planet, which takes place in parts aboard the confines of an even smaller star vessel that has spent over one year traveling sixteen light years from Earth to the exoworld Altair 4, they referred to a similar situation with their own new term: Space blues, with one remedy for it being shock therapy! FYI: The term and the subsequent discussion on these space blues did not make it into the final cut of Forbidden Planet; sadly, its mention was only in the 1954 draft script.

COMMENT 2: Both science fiction films considered the ideal crew for deep space missions to be structured like a military expedition with combined services, complete with the expected military levels of discipline and order. In addition, in specific regards to Forbidden Planet, the starship crew of the C-57D was described at one point by its captain as “nineteen competitively selected super-perfect physical specimens with an average age of 24.6 years.”

“Self-induced?” queries Merritt.

“Well, not consciously, of course,” Elsbach begins, with Fodor noticeably walking off to another part of the room where he busies himself while still paying attention to their conversation. Judging by his body language, one can tell that Fodor knows where things are probably going for Sergeant Cooper.

“Each mind has its own limits of endurance, at which point it rebels. The result can be anything: Simple hives, hallucination, headache, loss of speech, paralysis, total insanity, anything.”

Elsbach shuts off an examination light, then continues his lecture.

“ALL of us up here suffer from the same disease to some degree. It is to be expected. Man has never before lived in space. Fortunately, most of the cases are so minor they present no problem.”

“But Cooper?” Merritt asks.

“Cooper will be perfectly normal… as soon as you return him to Earth.”

“That bad?”

“What he experienced was simply a warning,” Elsbach explains. “If it happens again, it could be permanent.”

“I see,” says Merritt, mulling over what he has just learned. “How about the others?”

“Andre, Imoto, excellent,” begins the doctor, who looks over at Fodor, who looks back and then walks out of view.

“As for Siegle, Sanella, and Donkersgoed… every day with them, it is a new set of horrible afflictions.” This comment makes Merritt laugh knowingly. “Some of them completely unknown to medical science.”

Doctor Elsbach continues with his analysis.

“Furthermore, they all seem to have an absolute loathing for the Wheel, its commanding officer, its doctor, a certain Sergeant Mahoney, and the Space Corps in general. Everything, with the possible exception of good food…” Kurt pauses slightly to place a smoking pipe in his mouth “…and women.”

“In other words, they’re normal,” Merritt concludes, amused. “Thank you very much, Major.”

COMMENT 1: I just had to look up the last name of Donkersgoed, one of the lunar mission crewmen mentioned by Major Kurt Elsbach and whom we met briefly back on the spaceship. It is a real surname, but according to one Internet site it is only the “1,058,336th Most Common surname in the World,” which is not very surprising. Donkersgoed appears to originate from The Netherlands, which ties in with Conquest making an effort to show how international in composition this retro-futuristic space program is. In this paragraph alone I have already given essentially more attention to this poor fellow than he will receive in the entire released film!

COMMENT 2: For the record, Elsbach is a Dutch name. It is also the name of several tributary rivers in Germany. Siegle is a variation on Siegel as well as Segal and Segel. It is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname going back to at least Eleventh Century CE Bavaria. Siegle and its variants denoted people who made wax seals for official documents or sealed them.

COMMENT 3: The actor who played Jackie Siegle, Phil Foster (1913-1985), was born and raised in Brooklyn (his birth name was Fivel Feldman). Before being hired by George Pal for his role in Conquest, Foster had made several popular short comedy films as “Brooklyn’s Ambassador to the World” for Universal-International. At least he was the genuine article.

Having left the infirmary, Colonel Merritt is next seen walking through a corridor towards yet another hatch, this one with a crewman in beige working on a small black control panel next to it. Suddenly Merritt pauses to lean first against the panel and then the door, gripping at the hatch wheel (also known as a door locking wheel, speed wheel, and a dog when referring to one on a submarine) in some kind of apparent distress.

“What’s the matter, sir, are you ill?” asks the concerned crewman, who prepares to steady the Colonel in case he starts to fall.

“No,” replies Merritt, standing up fully. “No, I’m all right.”

The crewman attempts to open the hatch for Merritt, but the Colonel quickly grabs the wheel and does it himself, forcing a smile on his face and telling the man to “carry on” before leaving the corridor and shutting the hatch behind him.

Alone in his office/quarters, Merritt shakily goes over to a wall and slides open the white panel there to reveal a half-hidden compartment behind it. From there he removes a small transparent container holding a white powdery substance and places it on top of the cabinet. Merritt scoops into this substance just once and deposits the powder into a cup. He then retrieves a translucent bottle containing a liquid and pours it into the same cup. Drinking the contents, Merritt takes in a deep breath and seems to feel better.

The scene switches to someone holding a black-and-white photograph of a woman in what one calls a “cheesecake” pose and signed “Always Yours Jackie Baby”. As one might suspect, the owner of this photo is Sergeant Siegle, who is looking at the image in the barracks section of the Wheel with some of the other crewman. Generic “swing” music plays in the background. Various pinups of beautiful women adorn the far walls of their living quarters.

“My Rosie!” Siegle exclaims to the men around him. “Thank heaven science ain’t found no way to put you up in capsules.”

Sitting on a bunk next to a worried-looking Roy Cooper, Siegle lifts up the photo to Italian crewman Pedro Sanella lying in the bunk above him and waves the image in the man’s face.

“The future Mrs. Siegle, Pedro! How’d you like to paddle that around in your gondola?”

Pedro takes a brief look at Rosie and declares “for a wife, too skinny.”

“Too skinny?” exclaims Siegle. “That’s beautiful skin, boy!”

Mercifully, the camera diverts our attention to Roy, who gets up and walks over to Fodor.

“Andre, what did they say?” Roy asks his friend. “I’m not out, am I?”

“Out of what, Roy?” Fodor inquires in return while wiping his right ear with a small towel after having taken a shower.

“The Spaceship. It must have a crew.”

“Now, look, Roy,” responds Fodor, taking on a reassuring tone, “the Colonel hasn’t told us definitely we are the crew.”

“We don’t have to be told,” Roy shoots back. “We are, you know we are.”

Roy then goes into an exposition not only to support himself but to explain the background of the mission crew to the audience. The men around Roy stop what they are doing to listen to his words, which become more frantic sounding with each new sentence.

“Every man on the Wheel won his place after six months of the stiffest competition in the world,” Roy begins. “Each one of us were handpicked from the winners for this special duty. Who else is being conditioned as we are? Special food, special exercise. Tests, lectures! Watched every second! Never any leave!”

Tightly gripping a metal bunker support pole, Roy becomes aware of how he is sounding and pauses, looking around at no one in particular, but now speaking to everyone present.

“You fellows know how… how tough it’s been. Now, just because I had a… bad couple of minutes out there….”

Feeling distraught and ashamed, Roy turns away from the group. Fodor silently gestures to Pedro Sanella to say something to cheer up Roy, or at least distract him.

“That’s funny, I didn’t think to have a bad couple of minutes myself!” Pedro jokes. The men laugh at the comment in support.

Sergeant Siegle automatically gives his opinions on the matter.

“I don’t think we’re going no place,” he claims. “AII right, so we built a spaceship. That doesn’t mean we have to fly it.” This is in direct contrast to Donkersgoed’s earlier comment of “we build this ship, so we fly it.”

Then Siegle comes up with both an alleged insight about their mission and his personal future plans all at once.

“Hey, maybe we’re guinea pigs!’ he declares. “Maybe they wanna find out how much of them cosmic rays a human carcass can absorb before we light up like Christmas trees. And at double pay, I can learn to like cosmic rays! With all that loot, boy, I’m gonna open a TV shop, settle down, marry my Rosie, and raise a houseful of kids. So if I glow a little in the dark, she could find me better!”

“If you get that charged with cosmic rays,” Imoto responds with some bemusement, “you’d better not plan on too large a family.”

“That’s a lot of borscht!” is Siegle’s “scientific” answer to Imoto. “One of them cats in the lab just had a litter of seven kittens, and she’s been up here longer than we have. And anything a cat can do, me and Rosie can do too.”

COMMENT: The gestation (pregnancy) period for your average domestic feline is about 65 days, or two months. As these crewmen have been on the Wheel for approximately one year now, not counting any other time they may have served in Earth orbit, this likely means there is a specialized in situ breeding program going on in the station – unless the cat was artificially inseminated via frozen sperm stored onboard earlier. I also wonder what other animals they may have on the Wheel for testing biological processes and responses to long-term exposures to the space environment?

Even in the pre-Space Age era when Conquest was released on the big screen, various fauna and flora had already become the first space explorers aboard suborbital rocket flights. The United States often preferred monkeys (and later evolving to apes such as chimpanzees) as their test subjects, while the Soviets favored dogs. Animal astronaut and cosmonaut missions would only increase as the Space Age turned into a Space Race. A few cats were later a part of the Animal Space Corps per se, but they were not a preference by the major space agencies.

Space Smorgasbord

Just then a two-tone chime sounds. The men excitedly rush to the barracks hatch.

“Last call for dining car!” cheers Imoto.

As expected, Siegle is even more basic and to the point.

“Food!” Jackie cries, flinging up his arms with joy.

Siegle, Imoto, Donkersgoed, and Sanella line up in pairs on either side of the hatch. They start a countdown in unison, getting as far as the number two when the heavy metal door swings open and Sergeant Mahoney appears in the entrance. He looks at the crewmen standing rigidly at attention.

“Shall we go, gentlemen?” Mahoney invites, laced with a bit of bemusement in his tone.

“Yes, Mother!” the four men respond as one in a sing-song voice and rush through the rectangular opening. Siegle goes through last, stopping just long enough to give Mahoney a playful and also mocking pinch on his cheek before heading on to the mess hall.

Roy Cooper is still in the barracks, leaning against a locker after his outburst. Unsurprisingly, Andre Fodor is there with Roy to offer some comforting gestures of support, which oddly include ruffling the hair on Roy’s head from the back. The two go to join the rest of their comrades.

In the long dining area of the Wheel, we see dozens of beige-clad men at the tables already well engaged in simultaneously consuming their dinners and enthusiastic multiple conversations. There is one table, however, that is conspicuously empty: Only a server is present, and he is in the process of completing the settings of plates, cloth napkins, white drinking containers that resemble formula bottles for infants, and one large platter covered by a napkin. This special table is meant for its next occupants, who just happen to be our lunar mission crewmen.

As the select group in blue march into the dining hall in single file, with Imoto in the lead, the rest of the crew stop eating and sit at attention. The men come to stand in front of their place settings, with Sergeant Mahoney strolling to his position at the head of the table.

“Be seated, gentlemen,” orders Mahoney, not unkindly.

The six crewmen sit down without hesitation. Just then, the rest of the members of the mess hall simultaneously stand up and burst into a “serenade” that leaves the special astronauts looking away, feeling conspicuous and embarrassed…

“Mahoney has six little lambs. /He has to watch their diet. /They helped the Colonel build his ship. /And now they have to fly it!”

The men in beige conduct a short-gestured synchronized applause, then laugh uproariously at their idea of humor before returning to their meals.

“Peasants!” Siegle shouts back at them.

“Dig in, fellas,” Mahoney says with a smile and an inviting gesture with his left hand towards the contents on the table.

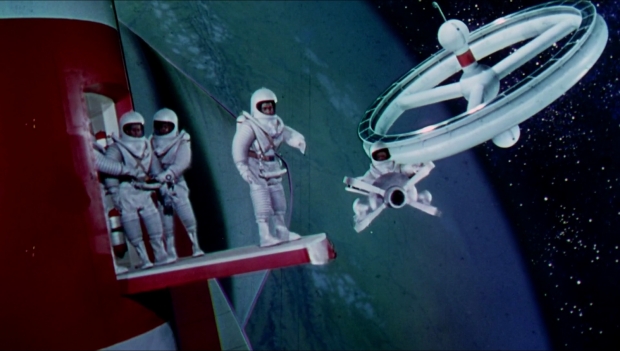

At last, we come to understand what Sergeant Siegle was complaining about back on the spaceship when said he had spent the last year “eating birdseed out of this goofy sombrero with no squawk”: Underneath that one napkin set before our men turns out to be a multilevel Lazy Susan spinnable platform painted primary blue with labeled compartments for many kinds of food and drink… all in pill form.

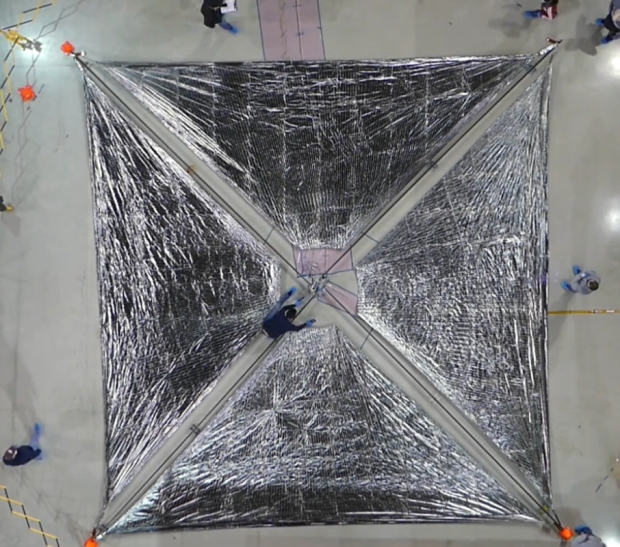

FIGURE 4. One of the more remembered scenes in Conquest of Space is the diet of our prospective astronauts: Not so much the food itself as the form it is in. Meals in a pill were one of the standard tropes of an imagined future for a technologically progressive humanity.

The camera closes in on the pill platter. Donkersgoed turns the platter a bit and selects several food pills from the tray, observing one of them grasped in his fingers with a lack of enthusiasm.

“Space smorgasbord,” Donkersgoed declares ironically to the rest of the table, before opening his mouth and popping in his dinner with a dramatic gesture.

Imoto, always the optimist, tries his portion and proclaims it is “pretty good today. Corned beef, I think.”

Holding up his quite compact meal, Imoto continues with his praise of this futuristic diet.

“Imagine… all the nourishment you need: No mess, no bother, and no waste.”

“I think I still prefer to eat the hard way,” Pedro Sanella concludes in turn. “Hey, Jackie! Pass me a cup of coffee.”

Sergeant Siegle picks out a coffee pill from its tray and gives it a short fling down to Sanella, who catches it.

Sanella looks back at Siegle and expectantly asks for “cream and sugar” with his coffee. Siegle obliges with the tossing of two more pills to his comrade.

Just then a server happens to pass by the lunar mission crewman’s table carrying a whole roast turkey for the other men in the mess hall. Siegle notices the cooked fowl first with his nose, then makes an exaggerated gesture with his head in its direction.

Mahoney looks at Siegle, disapproving of his behavior.

“Okay,” Siegle responds in a surrendered tone. “So I volunteered. So I’II eat.” Siegle goes back to his pills and then looks at Mahoney, who is also sharing in the rest of the crew’s diet.

“What are you eating it for?” Siegle asks the Irish sergeant, as if somehow this was the first time the man would have consumed the pills with them as well.

“Colonel Merritt eats it,” is Mahoney’s succinct reply.

“That’s a reason?!” Siegle says in astonishment.

“For thirty years, me and the Colonel have been banging around together,” Mahoney begins his answer. “Korea, Africa, China, now space. If he intends to shove off to anywhere else, I ain’t giving him any excuse to leave me behind because I ain’t eating the proper diet.”

Finished with his explanation, Mahoney looks down where the pill platter is presently residing on the table and asks Sanella for “some more of that corned beef, if you please.”

COMMENT: The staple and trope of many a science fiction story of the era was the consumption of food in pill form. In the Twentieth Century, as human civilization advanced and a desire for a more orderly world increased, it was considered and hoped that our most basic and strongest biological need, eating, would be rendered far less messy and uncouth with the turning of our meals into neat, compact forms. Condensing the food supplies for a deep space mission lasting for months or years would also be desirable in terms of not taking up precious volume aboard a confining vessel.

Would it actually work? Would we be able to survive on pills alone? Would we want to even if we could? This popular level article discusses this very subject, pointing out such important matters as our bodies requiring calories as much as we need nutrients:

The site Atomic Rockets did its usual fine job of discussing food pills and their issues. They even have two different views of the pill carousel from Conquest to accompany their segment!

http://www.projectrho.com/public_html/rocket/celss.php#id– HYPERLINK

Even if we can eventually succeed in making all our meals compact and clean, we may balk at them in the long run for the same reasons as some of the crewmen in Conquest grumbled about their pill dinners – made even more inexplicably torturous for them by being surrounded by the rest of the space station staff who are dining on full meals of meat and vegetables. Yet earlier, we watched Colonel Merritt chew out a crewman for merely mentioning a desire for ice cream!

We may have to change our very selves in order to truly adapt, survive, and thrive in space indefinitely before we can accept our nourishment in any other manner than the way we consume food now. Perhaps if we go that route, we may discover methods that do not even require our need to be organically fueled multiple times per day, if at all.

Mahoney turns his attention to Roy Cooper, who is lost in thought.

“You feeling better, son?” he asks Roy.

“Oh… fine,” Cooper responds without much conviction. He then has a question of his own for the sergeant.

“Mahoney,” Cooper begins. “You know the Colonel a Iot better than the rest of us. You don’t think he’ll wash me up?”

“Stop worrying,” Siegle interjects. “If he’s going off on an excursion, who’s he gonna take? He’ll have to ask for volunteers again. Us? That son of his?”

Siegle continues with a rumor he has heard elsewhere.

“I happen to know by the grapevine that the Captain has already put in for a transfer,” reports Siegle.

“So that leaves you,” Siegle says to Cooper. “So I hope you and the Colonel will be very happy together!”

Siegle suddenly gets distracted by declaring to all around that the current pill in his mouth “ain’t kosher corned beef!”

Mahoney, however, is much more interested in what Siegle had just said about Barney Merritt.

“So, the Captain put in for a transfer, did he?” Mahoney asks to confirm this news.

“Well, good riddance, I say!”

“He’s a fine officer,” Imoto replies in Barney’s defense.

“He doesn’t measure up to his father’s belt buckle!” Mahoney shoots back. “You know, I was with the Colonel the night he got the word the kid was born. We were in Indochina. We did a little bit of celebrating.”

Smiling at the memories of that night, Mahoney continues.

“I remember the Colonel – captain he was then – pointing up to the sky and said: ‘You see that Moon? That’s his birthday present. Someday I’m gonna give it to him.’

“A balloon on a string would mean as much to the ingrate!” Mahoney growls, clearly disgusted with Barney’s disloyal behavior towards his own father. “Putting in for a transfer!”

Mahoney’s rant is interrupted by a server wearing a chef’s hat carrying a large tray with various covered dishes to their table. The server places them before Roy Cooper.

Cooper looks up at the server with surprise and concern.

“This is a mistake,” he says.

“No mistake,” replies the server. “Compliments of Colonel Merritt.”

The server removes the covers from the dishes, revealing a full and delectable-looking meal identical to what the rest of the Wheel staff is consuming. Roy’s crewmates stare at the plates of unconcentrated food and hungrily announce out loud what they see before them.

“Steak!”

“With mushrooms, yet.”

“Asparagus!”

“Go ahead, Roy,” Fodor gestures. “Dig in.”

Cooper looks around anxiously at the rest of the men.

“Looks… looks delicious, doesn’t it?” he says, trying to be enthusiastic about this “gift.”

“Go on, cut it,” demands Siegle. “Cut that steak!”

Cooper picks up a knife and fork. With a bit of hesitation, Roy starts to slice into his steak.

Siegle, staring at Roy’s full plate, can barely contain his desire for real food.

“Man, that juice.”

With a piece of the steak impaled on his fork, Cooper starts to move it towards his mouth. Suddenly the man stops, knowing what all of this really means for him, and angrily slams his cutlery down on the tray before running out of the mess hall in frustration and shame. Fodor immediately leaps up from the table and runs after his friend out through the hatch.

The table remains silent for a moment. Then Imoto speaks to Siegle.

“You were saying, Sergeant Brooklyn?”

“I was saying, Sergeant Imoto,” Siegle replies. “If it wasn’t for a certain fatheaded stool pigeon just waiting for me to do it…” Siegle stares meaningfully at Cooper’s meal on his left. “Man, I’d be lapping up that steak juice…”

COMMENT: For those of you concerned as to the fate of our poor Sergeant Roy Cooper after being humiliated in front of his colleagues and subsequently washing out of the Space Corps manned lunar program, you will be pleased to know that Roy later changed his name to Bill Owens, joined the United States Navy (USN) where he reached the rank of Captain, and even designed a nuclear-powered submarine called Proteus. Originally designated U-91035 and meant for the study of the spawning habits of deep sea fish, the Proteus and its designer were recruited as part of the CMDF, which stands for Combined Miniature Deterrent Forces. Captain Owens and a small team of mostly medical experts would go on a critical top secret mission where no one had gone before as part of the West’s multitudinous Cold War efforts.

Sergeant Siegle’s declaration of “love” for Roy’s cattle meat is abruptly and violently interrupted by what sounds like a very loud explosion. The mess hall tilts to one side, sending its occupants falling and sliding down the deck and across the tables, knocking over trays and plates of food.

COMMENT: One could say that the mess hall became a real mess… hall.

The view changes to space, where the Wheel is being rocked by a collection of bright flashes along one side.

“Meteor, sir!” a crewman shouts to Colonel Merritt in the control room. Clinging to the edge of a wall panel, Merritt barks orders to his crew to evacuate and seal off certain sections and then fire the Wheel’s exterior jets (rocket thrusters) to stabilize the careening station.

We watch several men in spacesuits sealing off small holes in the station’s hull made by the impacting meteoroids with round metal plates held in place by air pressure. This emergency team is simultaneously busy putting out several mechanical fires with extinguishers.

Slowly the Wheel stops rocking and we return to a relative sense of safety and peace, signified by that same ethereal music as heard before.

Back in the mess hall, most of the men are attempting to pick each other up from the deck, with some staggering about groaning in pain and discomfort. Sergeant Siegle, who has somehow acquired several large pieces of turkey meat, emerges with a very different reaction to this event than his companions.

“Boy, oh, boy, what a fortune I could make with this thing at Coney Island!” Siegle shouts to several men in front of him who are otherwise occupied. “Boy, I’m telling you!”

Mahoney stares at Siegle: The man from Brooklyn not only has a big chunk of turkey in his hands, but also a smaller piece of the quite deceased and roasted bird dangling from the front pocket of his uniform. Siegle returns the look to Mahoney and defiantly bites off a mouthful of meat before walking away with his prize.

COMMENT: Rather surprisingly, the man from Brooklyn is apparently never reprimanded nor otherwise disciplined for this defiant act. We also never learn if the sudden introduction of solid food after a year of eating only pills would interfere with his digestive system. That Colonel Merritt saw no issue with having Roy Cooper served similar food after his own year of consuming pills may mean that such concerns are unwarranted, or they found a way to assist the human body in safely switching back.

Floating in a Most Peculiar Way

Some time later we are shown the smaller viewscreen witnessed early on aboard the Wheel in Conquest. Once again, we see on this very screen the white contrail of a rocketship slowly growing as the craft heads towards the space station. Captain Barney Merritt is observing this visitor carefully.

“Landing crew ready to make fast,” the Captain orders. “AII stations manned. Let’s go.”

With dramatic rising music, the winged ship arcs upward and then stops at an equidistant point between the big winged spaceship and the Wheel. Seemingly seconds later, a large metal hatch opens in the side of the red striped rocketship.

A small group of spacesuited men, each carrying a single duffle bag cradled in their left arms, emerge from the opening to walk slowly and a bit clumsily across the hatch, now serving as a sort of gangplank extending into space. The reason for their ungainly gaits is due to the magnetic boots in their suits holding them to the metal door.

The first man in line reaches the end of the hatch, where he is given a push on the back by the man behind him, sending him flying towards the Wheel. The scene is repeated three more times; with the same ethereal music, the first four men in this party drift in the direction of the space station, apparently without any obvious means for guidance correction or stopping when they arrive at the giant wheel.

There are just two men left at the delivery ship. One of them is staring rather apprehensively at the other men who are receding into the distance. His companion notices his fellow’s concern.

“It’s okay, Mr. Fenton. Don’t be afraid,” the astronaut says, adding a series of reassuring pats on his covered shoulder. “You’ll just float over.”

The man gives Mr. Fenton the requisite push, but not with his hand on his companion’s back like the others. Instead, he gives Fenton a shove with his foot on the man’s hindquarters! This sends poor Fenton tumbling end over end towards the Wheel, undoubtedly increasing his anxiety and perhaps even making him feel spacesick in the process.

COMMENT: Was this scene meant to be a deliberate joke for the audience? It may look amusing in a base way, until you realize the guy who got the literal kick in the pants was already scared being out in open space and has now probably graduated to outright terrified, flipping over himself repeatedly with no personal means of control. There is also the matter of treating a guest with respect, unless I am missing some aspect of traditional/contemporary military culture behavior?

This Fenton is clearly not used to conducting an EVA (extravehicular activity) – yet they shove him in the direction of the space station and just assume he will successfully arrive there. What equipment and protocols did the Wheel have to keep those visiting the station in this manner from either crashing into the station or missing their destination entirely, going off into the void with perhaps only a few hours of breathable air in their spacesuit between rescue and doom.

Perhaps the station crew thought they could just send one of their space taxis after Fenton in case he did miss the station, but then why not have this obvious VIP (Very Important Person) picked up by the taxi at the delivery rocket in the first place? It is just amazing, and not in a good way, how they (the crew and the script writers by default) thought it would not be a problem to have people just drift over from one vessel to another in the vacuum of space without so much as a jetpack or tether line – especially if they are new or otherwise unaccustomed to space travel.