As we move into the outer Solar System and beyond, the possibility exists that we may encounter an extraterrestrial species engaged in similar exploration. How we approach first contact has been a theme of science fiction for many years (Murray Leinster’s 1945 story ‘First Contact’ is a classic treatment). In the essay below, Ken Wisian looks at how we can develop contact protocols to handle such a situation. A Major General in the US Air Force (now retired) with combat experience in Iraq, Afghanistan and the Balkans, Ken brings a perspective seasoned by command and a deep knowledge of military history to issues of confrontation and outcomes, building on our current rules of engagement to ask how we will manage an encounter with another civilization, one whose consequences would be momentous for our species.

By Ken Wisian Ph.D

Galactic Ventures LLC, Austin, Texas

Abstract

How do two ships approach each other in a first contact setting? When it happens it will be a pivotal moment for human history. The slightest mistake or misperceived intention could cascade into violence. Therefore even future deep space robotic probes, let alone a true interstellar ship whether crewed by humans or AI, should incorporate courses of action for this possibility,

The development of first contact protocols is obviously rife with unknowns since we only have a one-planet historical data set build on; nevertheless we must proceed. The bulk of the thinking on first contact so far has focused on a remote contact via electromagnetic signal exchange (SETI) or finding non-sentient microbiota (aka Apollo post-mission quarantine), but what if we stumble upon another intelligence in space? Admittedly, this may not be the most likely course of action, but as we start to move deeper into space it is an increasing possibility. Through centuries of trial and error, protocols have been developed for military ship and aircraft encounters on Earth. These earth protocols provide as good a basis as we have for building extraterrestrial first contact protocols.

This paper will review human rules of encounter currently used and build a set of simple rules for a ship-to-ship encounter in space based on the assumption that there is no effective communication prior to or during the encounter.

1. Introduction

How do you approach a totally unknown entity in such a way as to not provoke a hostile reaction? This is not as easy a question as it might first appear. We are loaded with human-cultural preconceptions that are frequently subconscious. An example; smiling in humans is universally regarded as a friendly gesture, but in some primates and most species on earth (with a face that is) showing your teeth is a dominance/aggressive/threat gesture. And this difference here on earth exists between closely related species – who is to say how divergent the interpretation of gestures might be between species that evolved in different star systems? Another example is the white flag. Most industrialized states recognize it as a sign of surrender, some also would recognize its use to request parley, but it is far from universal in time or across cultures even today on earth. Thus nothing can be taken for granted and substantial on-the-spot sound judgement will be required.

Why worry about the vanishingly small chance of an unanticipated first contact? Risk management both in the military and civilian world considers not just the probability of an event, it also considers the potential consequences. In the case of a first contact, the odds of such an event are nearly vanishingly small, but they are cancelled out (and then some) by the off-the-chart potential impact of an encounter unintentionally entering an instantaneous, violent escalation spiral. Thus it is critically important that humans think through first contact in space before it happens.

Science fiction (SF) deals frequently with first contact scenarios. The volume of material is immense – far too much to even briefly review here. SF has explored, often quite well and with great “outside the box” thinking probably every conceivable scenario. So while there are no specific SF references here, the body of SF work informs all aspects of this paper.

We have a limited knowledge base from which to start and extrapolate general rules for first encounters, namely one technological species – homo-sapiens. This situation presents a danger that we must guard against as best we can; anthropomorphic bias. Given that potential bias, we will none the less start by looking at what humans do in the closest analog we currently have for first encounters; the meeting of unknown, neutral or potentially hostile ships and or aircraft. Through trial and (often fatal) error there are now well-defined rules of conduct for these situations (up to the level of international law).

The human-human contact experience is perhaps our best foundation upon which to build a set principles and protocols for a potential encounter in space. The envisioned scenario; two ships meeting in space rest on several assumptions.

Assumptions:

1. No effective telecommunication. There may be attempts to communicate via electromagnetic or other means, but understanding has not been achieved, thus we are without effective communication – “comm-out”.

2. Neither side is overtly hostile, but both are guardedly cautious.

3. At least one of the ships involved has “reasonable” maneuvering capability.

a. This will most likely be an “endpoint” encounter, in a solar system. An encounter in transit in deep interstellar space would likely mean neither ship has the ability to stop and/or maneuver in order to match vectors and effect a rendezvous.

Not a scenario assumption, but an important point is that these protocols apply just as well to Artificial Intelligence (AI) crewed ships as they do to human crewed ships. Also, ships is taken to include space stations or other similar outposts. Even probes without true AI can incorporate complex, branched Courses Of Action (COAs) for dealing with encounters. For instance, detection of radiation anywhere in a wide range of EM frequencies that does not correlate with known astronomical sources would be a target to slew all sensors to and report on. At that point, depending on level of sophistication, you enter COAs for determining artificiality etc.

Image: Confronting the unknown. A still from Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Credit: EMI Films / Columbia Pictures.

2. Current human protocols

There are internationally accepted protocols for encounters between ships and correspondingly between aircraft. Some are based on international law and custom (Law of the Seas), some are rules by governing bodies (International Civil Aviation Organization). Similar laws and rules exist also within the boundaries of individual countries. Regardless of origin, they follow broadly similar, mostly common sense (at least to us nowadays) paths based on centuries of experience. Underlying much of this is an unwritten intent to minimize potential misunderstanding that could lead to violence. This point is critical for our purposes. It is difficult enough to minimize misunderstanding and escalation within our own species, it could be significantly more difficult to do the same when civilizations from different stars meet.

Much of the law and customs for ships at sea pertain to piracy or the right of a country to inspect a ship to ensure that it is conducting legal business (particularly in territorial waters). Even here though reasonable cause is required for more than a cursory inspection. The rules governing intercept of aircraft are more slanted towards the need to immediately protect a country from devastating attack that can result from a craft moving at or above supersonic speed and thus can lead much more quickly to lethal action.

In all air and sea cases there is a hierarchy of communication means used to establish meaningful dialog between ships from straightforward radio communication to flag and light signals up to and including weapons fire – the shot across the bow, so yes, even gunfire can be a form of communication. With aircraft there are no flags, but brief maneuvers (such as rocking wings) can be used for communication.

For ships at sea, there are rules for avoiding collision such as pass to the right (starboard). There is also a rule that the most maneuverable ship has primary responsibility to avoid collision. For example a functional ship at sea that comes upon a ship adrift, unable to maneuver, besides having a responsibility to help, is responsible to maneuver so to avoid collision. Correspondingly, the less maneuverable ship is obligated to maintain constant speed and heading or come to a stop. For aircraft meeting aircraft there is a similar most maneuverable has primary responsibility to avoid collision rule, so for instance a powered aircraft has responsibility to avoid a hot air balloon.

For military aircraft or ships meeting other military ships or aircraft there are additional guidelines that are critical for avoiding escalation. First is to avoid collision courses or aggressive maneuvers such as those designed to put one in a (better) shooting position. Right along with that are restrictions on pointing guns or (and this gets tricky) putting support systems such as radars into modes such as target track that are standard preparatories to firing weapons. Radar modes have become particularly problematic as technology has advanced; many weapon system no longer require a distinctive target tracking mode in order to shoot. Furthermore electromagnetic jamming during an intercept is a potentially hostile act. These rules unfortunately are not universally followed and not following them has resulted in very serious international incidents to the present day.

3. Excursion into past human civilizational first contacts

The past record of human civilization first contacts is a well-trodden area of history and will only briefly be covered as it pertains to extraterrestrial scenarios – the longer term consequences such as disease transfer and cultural domination will not be addressed. Less commonly studied though are the details and consequences of the actual first contact. The bottom line is that first encounters have often, though not always turned violent and in such cases the side with a major technological advantage usually wins. Commonly Western Europeans with well advanced gunpowder technology encountering stone or bronze/iron age technologies have won most violent encounters, but have sometimes been overcome bu numbers. The question of why encounters have turned violent and the cause is much more ambiguous – some encounters have been peaceful, but in many cases territoriality and xenophobia have been prompt causes for violence. Who can say for sure that any species encountered may not have these traits (even more markedly than humans)? Perhaps more disturbing, there are human cultures that consider war/killing a necessary prerequisite to full citizen status. Fortunately none of these cultures are dominant on earth today, but what if such a culture achieved an interstellar civilization?

4. Towards a protocol

The above review of human encounter situations and history gives us a good starting point for thinking about alien ship to ship encounters. First a few general principles to go with the assumptions already laid down at the beginning. These principles are distilled from the human contact procedures above which in turn are built upon millennia of experience.

Contact principles

- 1. Be predictable

- 2. Avoid any appearance of hostile intent

- 3. Attempt communication

These seem straightforward, but #2 has many subtleties and #3 is a very complex subject which is beyond the scope or this paper or the expertise of the author.

The principles are in priority order; communicating is far less important than the closely related ideas of being predictable and not showing hostile intent. These principles are broadly applicable in human experience. For example besides applying at the level of international affairs, these are also appropriate at the level of individuals for an encounter with law enforcement around the world, driving a car, or encountering strangers on the street.

What has not been stated before is the underlying motivation for these principles and that is to avoid putting the other party into a position where they have to make a snap judgement about your intent. In human interactions between two wary parties ambiguity of intent is almost always interpreted in the most hostile way (unless the parties have a considerable experience base, which in a first contact they will not, that allows them to presume accidental ambiguity versus hostility). It is also important to note that for the foreseeable future, considering that we have only just become a spacefaring species, we are most likely to be the less technologically advanced of the two encountering civilizations and thus it becomes particularly important that we not precipitate any escalation that we are very likely to lose.

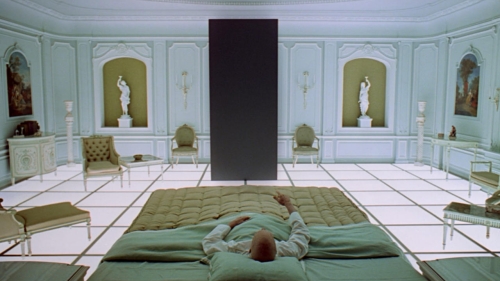

Image: David Bowman (Keir Dullea) and a famous monolith, from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Credit: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

First, be predictable. Being predictable is taken to mean with respect to maneuvering primarily. If it is possible to determine that one ship has a decided maneuver advantage on the other, then rendezvous can be attempted with the ships adopting the convention of the most maneuverable ship takes primary responsibility for a safe rendezvous. In these cases gradual, deliberately slow maneuvers would be employed even if there is capability to rapidly affect course changes. With regards to maneuvers there are multiple COAs available. The simplest is to make no changes to what you are doing; if “coasting” – continue, if drive engines are engaged, continue at current setting. Alternatively, you might want to stop engines (this is not the same as stopping in space, which is probably not a practical thing to do (for that matter what frame of reference would you use to determine “stop”)). Regardless unless there is an overriding need (discussed shortly), maintain heading (in three dimensional terms – maintain vector).

What if one ship is approaching an orbital situation – remember that an encounter will most likely be at the endpoint of an interstellar journey. In such a case, in order to avoid catastrophe it might be necessary to start or continue maneuvers to achieve a safe, stable orbit, but this brings with it a slightly elevated risk misunderstanding. In this situation we would be forced to rely on the other parties’ ability to perceive the obvious need to conduct maneuvers. Note the potential for unintended consequences; for a ship that would need to “flip” end-to-end in order to reverse its engines and thrust, you would not want to “sweep” your thrust vector across the other ship and therefore place them in a position of having to decide if you are about to use you most destructive weapon (main drive) on them.

Secondly, avoid any appearance of hostile intent. This is a much more problematic issue than being predictable. The main problem with avoiding appearance of hostile intent is the perception problem. In any encounter between entities that do not share a common culture, there can be serious misinterpretations of intent and meaning, as exemplified by the smile and white flag examples earlier.

If a ship is equipped with weapons you would obviously not want to point them at the other ship. If practical stowing or deactivating them is good, but this then poses another question: would you want to have weapons that require time to activate completely deactivated, thus costing valuable time to spin up if things go bad?

Besides weapons, other non-destructive systems are used by the military; jammers and expendable decoys for example. These would obviously not want to be triggered (but what might be the difference between jamming and a high-powered attempt at communication?).

“But we are peaceful and will not be going armed into space” you say. Any conceivable ship will have technology/systems that are dual-use. The main drive of any self-powered interstellar ship will obviously be extremely high energy and could be used as a weapon of great range and destructive power, thus even a peaceful braking maneuver (with the drive off) that sweeps the business end of the drive towards the other ship, could prompt a swift reaction. Other systems that must be accounted for include communication systems; radios or lasers strong enough to communicate across interstellar distances could be very destructive at short range. So what is one to think when you see a high power laser move to point at you? Perhaps part of a communication protocol would be to only use low-power omnidirectional radio until good understanding is established. Shielding to protect ship and crew from radiation and or collisions has obvious military application – do you reduce its power, turn it off, or leave it in normal on mode? Can you? What if there is an active collision prevention system that destroys or pushes objects out of the way – that has major weapon potential. Is it safe to turn it off?

Tertiary considerations. Avoid looking like you are hiding (aircraft that turn off transponders are usually considered to have hostile or at least illegal intent). Turn on lights and anything else that makes you easily visible (but will this in turn blind any of the other ships sensors?). In your turn you will obviously use every sensor available to learn about the other ship, but passive sensors are probably best until goodwill is firmly established – an active radar scan may look like targeting to another party (just as targeting and search modes of radars are often indistinguishable in modern aircraft). A decoy, a probe, or a vessel containing materials to allow for communication and understanding, might be indistinguishable from a bomb, when launched from a ship.

Lastly, at what range do these actions need to start? As early as practical, probably at detection of the other ship. Your need to be predictable starts when they can see you and that is probably at least at the point when you can see them, if not much earlier.

5. Conclusion

What can be determined from the above discussion is that there are vast unknowns in any potential extraterrestrial encounter in space where effective communication is not established in advance. In these circumstances there are good principles to follow – be predictable, display no hostile intent, and attempt to establish communication, but the specific actions involve many gray areas where judgement, assumptions, or just plain hope, will be the guide. For any ship making an interstellar journey the scenarios must be “gamed” extensively in advance, but any COAs or checklist for an encounter should only be a guide/starting point. Flexibility, sound judgement and quick learning will be very important in these circumstances. The number one goal is to not put the other party in the position of having to make an instantaneous judgement about your intent.

You wrote ” but in some primates and most species on earth (with a face that is) showing your teeth is a dominance/aggressive/threat gesture.”

This is funny because this king of smile was very american at first. Now ,thanks to Hollywood ,you can find it elsewhere. Showing your teeth is sign of confidence and yes maybe of dominance but it is the american way not the human way.

Myself, I find the “american tooth display smile/grimace” very repellent. I dislike seeing photographs of young women in particular, showing off their huge sets of gnashers. Does anyone else feel this or am I some sort of pre – Hollywood throwback?

I suspect it is a post-orthodenture change. Just look at photographs of Hollywood actors earlier in the century. When I was young (in the UK) photographers just said smile, not “say cheese” (which forces the teeth to be exposed). prior to the age of photography, just look at paintings. How many have the study displaying their teeth? None that I can recall offhand.

On this subject, Hollywood has also resulted in a generation of kids who are very expressive with their arms and have very “mobile” faces. This is a result of copying actors on children’s shows. Now consider the idea that one should not move one’s arms when facing a stranger as that can imply a threat.

It is hard enough dealing with other mammals. Just imagine if an alien was some sort of insectoid organism with an exoskeleton and a need to vibrate its wings and legs to communicate.

Those early stories of starships meeting in space are great story devices, but with the technologies we can foresee today, that cannot happen. We would race past each other, even if we were both in world ships.

I believe I was Timothy Zahn, but I could be wrong, who postulated a first contact going south because the Earth ship tried to communicate by radio. Problem was, radio was the frequency the other race used to communicate with their dead ancestors and therefore was considered an overtly hostile act. It ended up starting a war. Ken, you chose a vey difficult topic. As you said about risk analysis I don’t believe there is a foolproof way of first contact. Even doing nothing and waiting for the other ship to initiate contact can be considered a sign of weakness in some cultures. But you have given us food for thought, and plenty of fodder for debate.

It will be interesting to see if–as thousands of years go by–that animal life is Nature’s favored avenue toward achieving spacefaring intelligence…I’m thinking of the movie The Thing, a spacefaring humanoid that was pure vegetable…Maybe some ridiculous ideas like that one belong in books like Alice in Wonderland…Variety seems to be favored by Nature but there may be an upper limit to such foolishness…Only humans have bought pet rocks…Human boredom often reaches far into left field…But how would we cope meeting a spacefaring intelligence that was NOT animal life?

It’s most likely that it would be machine, rather than organic intelligence. How might this affect the discussion? Would the machines be programmed

with the prejudices of their creators?

I have to wonder about these protocols given that humans and aliens will be likely extremely far apart technologically, culturally and biologically.

Humans don’t respect ant protocols and we may be in the same boat with advanced aliens. Too far apart to interact. Guessing how another species or machine will respond to our incursions is highly speculative at best. It might work best for humans interacting with pre- or low tech species, but I doubt this might be of much use unless we get very lucky and meet a another species that is close to us, technologically.

Interestingly this post include a scene from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Did the aliens behind te monolith have any protocols that are identifiable with the 3 suggested? AFAICS, NO. The monolith simply commandeered the pre-humans brains in the Pleistocene. The Iapetus/Europan monolith simple grabbed Bowman’s pod and sent him on his way to a fake Earth environment. No attempt was made by these advanced aliens and their machines to adhere to any careful meeting protocol. While I don’t think Clarke’s story has much validity for a real encounter, it does indicate to me that meeting with aliens will not be played by rules that we can model, but likely by rules the aliens use. Whether like the gentle approach in Sagan’s “Contact”, or the violent approach shown in so many invasion scenarios ever since Wells’ “War of the Worlds”.

That so many are wary of METI suggests that we might be wary of even trying to have any contact, and if the hiding civilizations is the solution to the Fermi Question, then so do other civilizations.

You’ve put your finger on something. We, and this is no insult, are apes. Our wired schema for “first contact” are based on interactions between primates. But interaction between species separated by truly vast evolutionary gulfs plays out very differently. Earth has had examples. When cyanobacterial met anaerobic life: our heavy-breathing ancestors didn’t mean to cause an extinction event, but they didn’t not-mean to, either. They were a vastly different kind of creature, and stole a planet simply by metabolizing. Intent, communication, diplomacy were no part of the story.

It’s a really big galactic cluster. Spacefaring biological or synthetic species with billions of years of adaptive heritage preceding them — and absolutely none of it in common — might be wise to observe one another over a great distance, at least for several brief millennia, before trying to get together.

I remember a story (novelette) by Murray Leinster called First Contact, which is about two starships from different races meet in space and they have to resolve this problem.

Wikipedia entry: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Contact_%28novelette%29

There are a few other assumptions here. One is that we, at that distant time, and aliens, would be psychologically similar to humans of the twentieth century. Given the expectation of genetic advances, this seems unlikely in the extreme. Another assumption relates to the goals we have in undertaking the star travel, and equivalently, what goals the alien civilization would have. It may well be that both could care less about the other, and the only important protocol would be not to bother the other. On the other hand, if we are in their solar system because we are going to colonize it, acting timidly may not be the best way to shape their perceptions of us.

Growing up in the fifties in Britain as I did, the girls at school never went in for prolonged public screaming. It would have been an indication of something enormously heinous taking place – a true warning cry in good old primate tradition. Then The Beatles arrived. On the USA side of the pond, the screaming of adult women at public events (TV show audiences, sports events, etc.) is now regarded as normal.

So when here, in the USA, I hear the scream of a woman through my open window, I disregard it. I mention all this to note that this changed within one generation. Thus reliance on social conventions with actual aliens is going to be fraught with problems.

One rule seems wise, however. For first contact, keep anything remotely connected to the military as far away as humanly possible, for as long as possible.

I find it extremely concerning that the interstellar probes we are designing via Breakthrough Starshot will be unable to meet any of the standards put forth here. A swarm of unmanned wafersats propelled via light-sail may be seen as extremely hostile by a civilization in the star system they are hurtling through at 0.2c. Numerous unforeseen effects could scatter the swarm, giving them little to no appearance of predictability. There is little to no plan for these devices to communicate with anyone other than us, sending data back to Earth, not outward to whom or whatever they might encounter.

Given that these probes will most likely be our medium of representation during any first contact, shouldn’t we be more concerned with their capabilities in this context instead of the speed with which we can deploy them?

Interesting subject. I agree with Dr. Wisian’s observation about Murray Leinster’s story “First Contact”, which I had the pleasure to read in the late 20th century.

I think we might do well to also look as best we can back into prehistory. I’m thinking primarily about the possible means of Neanderthal extinction (or at least dispersal) some 40,000 years ago; also of the likely battle scene in Kenya about 10,000 years ago. I would post links but there are so many good sources of information that I simply recommend using your favorite search engine as a place to start.

Opinions range from conflict being alien to humans to it being necessary for development and possibly needed as a motivation to move space ward (not to mention the fact that our planet may insist on this, with regard to environmental and other pressures). With this in mind, extraterrestrials may well be worth fearing, as Dr. Hawking is known to have expressed.

Lets hope for “first contact” to win out over “first conflict”.

This is all good until we encounter an intelligence the cultural equivalent of the Klingons from Star Trek. They would see the predictable docile approach as weakness and fire disruptors on us for being timid and having no honor. When approaching the Klingons you must fire a shot across their bow or at least target their weapons array to show you do not run from battle. The Klingons would respect that, and at that point you could beam down to the nearest moon to participate in contests of strength, drink blood wine and consume mass quantities of Gagh (served live of course).

I’m afraid there is no set of rules based on our own culture/species that could be useful in all situations. First contact (unless there is a prior exchange of culture/technology via long range comms) is always going to be unknown. The key should then be on establishing these remote communication exchanges first, before you bump into a Klingon warship unannounced.

“Science fiction (SF) deals frequently with first contact scenarios. The volume of material is immense – ”

Bravo! I love seeing that observation.

The fact that we humans have such a crappy track record in first contact history, and that (almost) our entire knowledge base is garnered from military tactics does not bode well for any of these potential scenarios to end well…likely resulting in the eradication of humans from the earth.

Wow, you have a flair for the melodramatic. Too bad we have knowledge of literally no other intelligent life form on which to draw a valid comparison. On what do you base your implicit assumption that we are not the most peaceful, timid species in the universe? I really enjoyed the use of the word “likely” in drawing your conclusion, it underscores the gravitas of your sentiments.

If they show up in our solar system, we might do best by following the example of planet Tivoli, where the Tivolians adopted perhaps the best survival strategy possible in their circumstances:

http://tardis.wikia.com/wiki/Tivoli

Given the historic examples of the colonisation of Africa, Americas, and Australasia, we should hope that aliens aboard ships approaching our shores bear no cultural resemblance to Europeans, and remember that the indigenous peoples who fared the best were those who remained hidden deep in the rain forest to this day.

It’s instructional to note that even with the best of intentions, today’s anthropological researchers still find it enormously risky to open up communications with such lost tribes without introducing them to innumerable modern ills. How much more difficult would it be for well meaning aliens to interact positively with human culture?

In these scenarios, science fiction (and unmentionable sources) have suggested techniques an alien race might use to enculturate human ambassadors off-planet, or for governments to effectively quarantine visitation sites and suppress awareness of their existence. Perhaps those techniques are wise?

No, that’s not true. The Japanese people fared best, because they were both tough and well organized, and also made a collective decision to learn as much as possible.

I suspect that at minimum alien contact will be as one-sided as Alex Tolley suggests. And it might be even stranger e.g. something like Solaris, where it’s not even clear that the alien(s) is/are aware of the human presence but the contact nevertheless has devastating consequences. We’ll be lucky if aliens appear as something we recognize (and that recognize us) and can interact with on mutual terms.

Tough questions which reach to the existential edge of ‘what if’?

When ‘pulsars’ were first discovered, it was speculated we stumbled into

a network of ‘E.T. lighthouses’!

No, just neutron stars. Vast amounts of ‘sky watching’ were overturned as our abilities gave rise to our current view of nature. Our self-importance is not necessarily indicative of arrogance, just cosmic ignorance.

To an advanced civilization, life forms technically adept to travel beyond their home planet are ‘sufficient’ to be recognized as possible ‘new neighbors’? Or an environmentally uncheck able menace that usually goes

extinct in the cosmic short term?

I’d like to meet ‘The Guardian of Forever’, but I’d not want to be on the threatening side of a ‘Horta’ ‘Nomad probe’ or an ‘Excalbian’ !

Between ‘Star Trek’ , ‘Doctor Who’ , ‘Farscape’ & ‘Contact’ …. our galaxy could contain a variety of wonderful and malevolent cultures.

Worst case scenario , we are just too vulnerable & alone.

Best case scenario, we are part of an infinite diversity of Life and senior civilizations are reminded of the beginnings of their ancestors.

Let’s find the answer?

Mr. Tolley raises an important point: this discussion is about contact with a peer, or near-peer civilization, but the odds are very much against that. What’s far more likely is contact with a much less advanced civilization, or a much more advanced one. The two scenarios require very different approaches.

For a less-advanced civilization, the risks are 1) Harm to the crew or vehicle making contact, and 2) Harm to the contactee civilization.

Averting harm to the crew or vehicle defaults to Mr. Wisian’s very useful principles described in this article — with the proviso that a pre-spaceflight civilization might not fully understand things like, e.g. laser communications, Orion pulse drives, or even the need for highly energetic orbital maneuvers on arrival. On the flip side, their detection abilities would be correspondingly less effective, and it might be feasible to observe them from orbit or by using small, concealable surface probes for a long time before making contact.

Averting harm to the contactees is alluded to by several other commenters here (though wrapped in a mantle of European guilt which suggests ignorance of the history of other civilizations). Some form of Roddenberrian “Prime Directive” seems inevitable, although I personally don’t consider making overt contact to be a form of “interference” which must be avoided. Let them know we exist and are ready to talk if they want to, but don’t make any subjective judgements about whether they are “ready” or not. (Was 20th Century Russia “ready”? How about the Buddhist empire of Ashoka in the second century BC?)

Obviously, methods to prevent biological contamination must be robust and utterly reliable.

The second situation, contact with a much more advanced civilization, is more dangerous. The risk of harm is not just to crew and vehicle, but to humanity in general. Again, Mr. Wisian’s recommendations provide a useful baseline for behavior.

With a more advanced civilization it may be impossible to prevent them from learning more than we wish — like, say, everything — about ship, crew, and humanity just from the initial contact. The flip side is that they may have done this before, and probably have thought about it. Their trigger fingers may not be as itchy, which is good because the results would likely be more catastrophic. Quite simply, they don’t need to be as fearful; they’re in the position of Australian harbor police dealing with the arrival of a canoe from an undiscovered Pacific island culture. As long as the newcomers aren’t a threat to individuals, nobody’s going to worry about the threat they pose to Sydney.

In both cases — more and less advanced civilizations — it seems to me that honesty is important. We won’t know how much they know about us, or how much they can discover, and the last thing we want is to be caught in an attempt at deception. This also means frankness about what will not be shared. “I do not wish to give you that information” is a better answer than a lie. Honesty also means a limit on covert observation. At some point you have to tell them you exist.

This is a valuable contribution to the debates about contact, drawing on real world experiences.

There are many analogs to first contact in human history. The consequences for the weaker party have ranged from benign to disastrous. Yet many involved in the debate about broadcasting signals to attract the attention of more technologically advanced civilizations dismiss concerns about risk.

As the author points out, our methods of dealing with confrontations at sea or in the air have evolved over recent centuries. They are the products of long experience, which we will lack in the case of first contact with an extraterrestrial technology.

Despite these well-established behavioral norms, potentially dangerous confrontations still occur here on Earth. In recent years, Chinese ships have behaved aggressively against the vessels of less powerful nations such as Vietnam and the Philippines, including ramming that caused casualties. American insistence on free passage in international waters or air space has led to many close encounters with Chinese and Russian ships and aircraft. It only takes one mistake by a captain or a pilot to turn a manageable incident into military action, despite the fact that American, Chinese, and Russian authorities share much historical experience.

I hope that Dr. Wisian’s essay will attract wide attention.

The recent first(?) contact with the natives in the Amazon was very much not good. Loggers and oil extraction companies resulted in a fearful contact. The government’s effort was to entice the natives out with trinkets in order to assimilate them. This behavior is rather 18th/19th century and very different from what we supposedly have learned. Not so different from the movie Avatar.

While “assimilate” sounds pretty immoral before you think about it, it is much more immoral to allow the natives to withhold health care and education from their children. So, assimilation is not only inevitable, it is also the morally right thing to do.

If there are superior aliens out there who know how to eliminate strife, cure all diseases and old age to boot, I’d be first in line to be “assimilated”.

Eniac, you make an excellent point – the notion that western civilization has “assimilated” the rest of the world is predicated on the implicit assumption that the various peoples of the world would choose instead to live on the human equivalent of game preserves, and engage in ancient customs, such as dysentery and back-breaking manual labor. This reminds me of a scene in “The Life of Brian”….what have the romans ever done for us?

I think the real problem will be referrants, i.e. references. Look at the relationship between the dolphin and humans. We communicate rudimentarily, lmost in a pigeon sign language. We have no idea how intelligent they really are even after decades of contact. We’ve learned much in those decades but still can’t swim up to a dolphin and whistle, “Hiya, Joe, what’s happening?” Wonder how well we’d do with another species as smart or smarter than us.

This is because not even a dolphin can swim up to another dolphin and ask for a rundown of what is happening. Dolphins just cannot do it.

Whatever dolphins have for a “language” is not suitable for telling stories, period. We do know pretty well how intelligent dolphins are. By some measures, they come close to us. But dolphins do not have the ability to exchange thoughts the way we do, and that is why they lack culture, religion, philosophy, science, technology, all the things made possible by the ability to tell stories.

I just had another thought. We do have one language which dolphins don’t speak but a space-going civilization would have to: math. This is not a unique idea. It’s been used many times in SF. Pi is a universal relationship in this universe. So maybe mathematics might be the source of common refrrants if you can past the first shots…

Uhhm, Pi is not regarded as the best way to think about the mathematical relationships within a circle even on Earth. Personally, I vastly prefer Tau. Mathematical relationships may be universal, but different civilizations can express the same ideas quite differently. The same will be true in space.

So how is using 2*Pi (which is all Tau is) “quite different” from using Pi? If we saw either encoded in some alien message, we’d know right away what it is. The difference is trivial and meaningless, obviously.

Unless you think that science and technology are possible without math, it is clear that the aliens must have mathematicians, and it would be naive in the extreme to think that mathematician on both sides would not be able to discern the fundamental truths of mathematics from trivial conventions like Tau vs. Pi.

I think you are missing my point, Eniac. I was not saying that the difference between Pi and Tau would confuse either us or an alien. My point was that people tend to glorify Pi as some kind of “universal truth”, going so far as to search for messages from God in the digits. But there’s a bunch of people who think we should use Tau instead of Pi.

My point is that aliens may express the same RELATIONSHIPS in very different ways. Sure, Pi vs Tau is not the biggest difference. But people on Earth have thought about mathematical ideas in very different ways in over the centuries. This casts some doubt on the idea that aliens will automatically understand every mathematical idea we try to express to them. Watch this SETI talk on this subject.

So such casual statements as “Pi is the universal relationship of the universe” can be a form of mathematical anthropocentrism. There’s more than one way of thinking about mathematical properties. You were probably taught the distributive property as a formula. But you can also express it geometrically. Who knows what an alien species will prefer? Such differences will not be trivial or meaningless.

In attempting to communicate with aliens, we should strip down the ideas we express to their most basic forms and avoid Earth conventions. As an example, aliens will probably never have divided an angle into 360 degrees, but they will likely recognize radians. And so forth. But to say, “oh, it’s math, aliens will get it” is sloppy and anthropocentric. It’s also lazy to just say “alien mathematicians will do the work for us”. They might, but if we want to communicate we should make our message as clear as possible to them. We should also demonstrate a willingness to get beyond our own conventions if we truly wish to find a universal language.

This is all very well, but it does not matter what aliens “prefer”. What matters is whether they will understand. The typical example, a series of prime numbers encoded in bunches of pulses, is one instance were the message cannot be other than loud and clear: We are here, we think, we know math, we want to tell you something.

If that is not a proof of principle for successful communication, I don’t know what is. Prime numbers, like many other concepts, are not “anthropocentric”. They exist, in the mathematical, not physical sense, for any thinking mind to discover.

But it does not have to be just math. Galaxies, pulsars, stars, atomic spectra, the periodic table of the elements, elementary particles, etc. are all things that are universal, with unmistakably recognizable features, that sufficiently advanced aliens will know about. They all can be used as common ground for communication.

Are you saying 2 pi’s are better than one :)

I’ve seen the SETI Talks link you posted Christopher and would advise everybody take the time to view it… it’s thought provoking.

The above is based upon misunderstandings of mathematics. E to the i pi equals -1 is universal.

If HAL 9000 had successfully killed the human crew of USS Discovery and then went on to run the mission by itself as the Artilect was designed to do in the event the crew was unable to, I wonder how the Monolith would have handled HAL coming through the Stargate? Would the Monolith ETI have accepted HAL as the highest evolved intelligence from Earth? Or was it looking strictly for organic beings?

Certainly if nothing else, HAL would have been able to process and deal with the situation better than Dave Bowman, who was so psychologically shocked from the experience he had no memory of who he was when he arrived (this is in the Arthur C. Clarke novel). Would they have bothered with the fancy apartment for HAL or used something completely different?

To my mind, the Monolith builders wanted a biological sample of their (4-million-year)-prior handiwork and may not have been too happy with HAL as he is technically ‘just’ a tool of their biological experiments. However, I’ve never thought of it quite like like how you propose, Ljk, so thanks for giving me something else to mull over….hmmm.

You are welcome Mark. I blame the organic bias in the story on the limits of how most people viewed computers at the time, even science fiction authors. Computing machines were not usually seen as our intelligent successors of evolution but rather as tools even if they were aware like HAL.

If you really think about the best representative from Earth to “meet” with the Monolith ETI would have been HAL 9000, not the organic creatures who were barely able to handle to concept of alien life let alone be prepared to communicate with it. I think Kubrick was actually trying to make that point by making HAL by far the most personable terrestrial in the film along with glimpses of Dave Bowman’s sheer terror while being confronted with the wonders of the Cosmos through the Stargate. Then note Bowman’s subsequent trembling like a captured zoo animal in his gilded cage. And according to Clarke in the novelization Bowman was so overcome by his experience he had even lost his memory along the way.

The humans in 2001 may have seen HAL as a complex tool of their mission, perhaps even a form of slave, but I think HAL instinctively (if that word applies here) knew it was better at the job and that is why HAL bumped off the crew to ensure mission success even more than the pretext of it being afraid of being shut off (killed) or conflicted by keeping secrets from Bowman and Poole.

“This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it.”

Joe Morris said on May 13, 2016 at 14:31:

“I believe I was Timothy Zahn, but I could be wrong, who postulated a first contact going south because the Earth ship tried to communicate by radio. Problem was, radio was the frequency the other race used to communicate with their dead ancestors and therefore was considered an overtly hostile act. It ended up starting a war.”

This is why we need to get past the old paradigm of Radio METI/SETI after over half a century and look into other communication methods. See here:

http://www.coseti.org/lemarch1.htm

And those who study the bioastronomy and ETI fields need to start thinking way out of the box to even have a chance of finding and communicating with any alien neighbors (the key word here is alien):

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=27889

I think a reasonable approach would be to assume all contacts to be hostile. If you go into a situation preparing for this, first contact situations could be approached constructively. The idea is to have a probe vessel heavily shielded, but with no weaponry; no means of aggression, baring the perception of the initial intrusion. We assume that the probe will be attacked. If it is struck by a lesser advanced civilization, it will mostly likely survive. This is important in many ways: it gives us data on their technology and their mentality, while showing the alien race a reasonable amount of information as well. What’s vital is that after the attack, we back off slowly to a certain set distance and then wait. We show in as many pantomimes as possible a non-aggressive stance. Of course I’m showing a human conceit, but advancing/retreating motions should be somewhat universally grasped to any civilization that has advanced even slightly into space. If the probe continues to be attacked we leave the system or we could deactivate the probe and let them destroy it if that is their want, or to have it for research as the probe would have nothing that could weaken our position and it might help alleviate their fears of the “unknown”.

Once this initial point has passed, communication can be attempted.

If the civilization is more advanced, (and warlike) they should have no problem destroying the probe and we’ve lost nothing unacceptable. (It would be disheartening, but again, this was planned for). Glorious human conceit again; an advanced society should recognize the concept of a probe, and understand what we are attempting. Their action from there we leave in their pseudopods.

I think your second case is not thought through. What the more advanced aliens are more likely to do is trace the probe’s communication back to Earth and capture the probe to dissect it and learn everything they can. They might even usurp the signal seamlessly and make us think all we encountered was a funny asteroid or a minor malfunction, no big deal.

Very interesting article! This is definitely something we need to think about before we launch starships or even probes. Unfortunately, there are so many unknowns in such an encounter that we cannot possibly plan for all contingencies. We don’t know how a completely alien culture would interpret our actions.

All the same, the general principles of being predictable, avoiding appearance of hostile intent, and attempting communication is a good starting point. We may not know what showing the white flag looks like in an alien culture, but pointing your main photon drive at another ship is likely to be perceived as a hostile or at least threatening act.

This is something that has been noted by SF authors and fans for some time. See the Kzinti Lesson at Nyrath’s fascinating Atomic Rockets! Pretty much any reaction drive powerful enough to be interesting (and star travel is definitely interesting) can be a deadly weapon at close range. The idea of “weaponized exhaust” takes on a new and deadly urgency when you are talking about terrawatt antimatter engine.

And then, what about active defense systems for vaporizing/deflecting bits of interstellar debris? Those could double as offensive weapons and missile shields. As Ken points out, even the beam from an interstellar communication system could deal damage at close range. Any starship will have some offensive capability, even without any purpose-built weapons aboard. It will be very, very important to avoid the appearance of hostile intent in any encounters between starships.

All this makes me wonder if, perhaps, there are already established protocols for encounters between starships among much older and more mature civilizations. Maybe, when and if one of our starship crews encounters an alien starship, it will not be them but we who fail to recognize the meaning of the white flag.

‘This is something that has been noted by SF authors and fans for some time. See the Kzinti Lesson at Nyrath’s fascinating Atomic Rockets! Pretty much any reaction drive powerful enough to be interesting (and star travel is definitely interesting) can be a deadly weapon at close range. The idea of “weaponized exhaust” takes on a new and deadly urgency when you are talking about terrawatt antimatter engine.’

I have thought about if we ever come into a new solar system from near c velocities -laughs- to a stop that the exhaust mater/energy will be very deadly when braking as the energy goes up to very high levels and all at once from the entire journey energy input!

Well, just don’t aim for their White House lawn as your landing spot.

Seriously though, while far off you would be a beacon and you would be wise to make a display of actively avoiding any of their systems real eastate, no matter how small. Would that be ok?

Space is big, though, so there is plenty of room for us to direct our exhaust stream away from that solar system’s planets and moons! So we don’t have to worry about it too much. Also, most exhaust streams spread out and dissipate quickly (except for a hypothetical laser photon engine or something), so it will only be deadly at close range–and space is rather big, as I said. It’s only the deliberate use of a torch engine as a weapon that we have to be concerned about.

And we really ought to have some secondary low-power thrusters for safe maneuvering near planets and other spacecraft. And some shuttlecraft with engines more suited to quick trips around the system and landing on planets. This is one thing Heinlein got wrong about torchships. You are NOT going to let a mass-to-energy conversion rocket land on a planet even if it has the thrust to theoretically do it.

The exhaust stream does not spread out so much at fractions of c, if say they start to brake at Saturn’s orbit that is still a strong beam that could damage a lot of electronics or irradiate spacecraft outside of a protective magnetic field. And as for the mass – energy drive this would work ok in an atmosphere, just draw in the atmosphere and use it as reaction mass or use an onboard material.

OMGoodness… now you want to steal their atmosphere too?! Ha ha. ;D

Another way humans can learn about interaction with, or “first contact” with non humans is to study our interactions with the varied animal life on Earth (and for that matter, interactions between species and also individuals and groups within species). Especially interesting might be primates, marine mammals, cephalopods, some bird species; and those that are commonly made pets: dogs, cats, etc.

I think we can potentially interact with alien life within our solar system; particularly at the icy moons of the gas giants. Sending probes to some of those, in hopes of tunneling down into the cold subsurface lakes and seas is not a new idea. There may be life there, and if so that life may include life which is at least as intelligent as some animal life on Earth. At any rate living creatures are likely to react to the presence of probes, especially if such life is motile. This is one reason why probes ought to be equipped with cameras, microphones, a variety of lights which operate at different wavelengths plus the use of a variety of temperature, pressure and chemical sensors.

It seems that any reasonably capable life forms there will react to the probes and such reactions can be recorded and transmitted to us. Given the long radio lag, it goes without saying that the probes would need some level of automation and AI control (and mobility). Perhaps protocols could be established for this kind of “first contact”. We could learn from such events and add to our knowledge base with respect to lower and perhaps even sentient life in terms of interaction with the probes and in the future with human explorers. All of this would of course help prepare us for such possible first contact events at interstellar objectives.

As has been pointed out, any contact situation is overwhelmingly likely to be similar to a coast guard ship intercepting a canoe. It will not really matter what interaction protocol the people in the canoe follow. “Do not attack” is about the only thing that makes any sense at all.

This SETI talk by Keith Devlin casts doubt on the universality of math for communicating with ETIs.

Contact with ET using Math? Not so fast. – Keith Devlin (SETI Talks)

In contrast, the late John McCarthy opined that there would be convergence in thinking modes for higher intelligence allowing us to communicate. I tend not to agree with him as the classic Nagel: “What Is it Like to Be a Bat?” suggests that we cannot think like bats and therefore might have a lot of difficulty communicating. However it does open up the issue of whether an AI that mimicked bats might be able to communicate even if it did not have the same type of consciousness as a bat. This leads me to wonder whether aliens would communicate with humans by mimicking humans. A trope of SF to be sure, and well done in the movie version of Sagan’s “Contact”.

It is all very well suggesting we don’t make hostile gestures, but if we were facing powerful machine aliens, might they not treat us as a “carbon unit infestation” and apply their equivalent of bug spray.

Having said all that, I find this whole conversation rather trapped in history. It is rather as if we are in the position of educating Captain Cook on how best approach Pacific islanders. In all likelihood any alien civilization is either very far away so that we will be far more advanced by the time we reach them, or they are already local, but unseen, explaining the Fermi question. If so, they are already aware of us and may already be “communicating” with us in ways we do not comprehend. Or we may just be alone in our galaxy, and be lucky if we even meet multi-cellular organisms that we can understand.

Protocol? Are we talking a Prime Directive, then?

More like what to do when the Enterprise encounters another alien starship of similar or more advanced technology and maneuvering capabilities. The Prime Directive applies to primitive pre-warp civilizations only. :-)

Prime Directive

The Prime Directive mostly excludes alien contact except under special circumstances. This protocol is far more proactive. The problem is that the world of Star Trek deals mostly with cultures that are few centuries apart in development. Only in a small number of cases (TOS, mostly) did Starfleet encounter vastly superior aliens. Even the Borg proved less powerful that expected and could be stopped by Starfleet. Their ships, like the Beserkers, were technologically understandable, just extrapolations of Starfleet level technology.

Fortunately the really advanced aliens seem to have little interest in Starfleet and federation worlds.

I think that the original post and comments have left out the “zeroth” protocol. Before doing anything else – “Notify the rest of the human race about the encounter”. Courtesy of Niven & Pournelle from Mote in Gods Eye, if memory serves.

Depending on your paranoia level, a consideration in this protocol is to avoid giving away the location of Earth and possibly other human colonies, before you know more about the other sides intentions.

Under the heading of “forewarned is forearmed”, a protocol for approaching a solar system for the first time, especially one that might host alien life of some kind, could contain elements like periodic pauses in the breaking program to enable high sensitivity observations of the target system. If you have something like a ” Star trek style warp drive”, initially warp out at a light year or two for an observation session and then progressively cut that distance, rather than blundering into a alien space party/yacht race/military exercise or what have you and potentially aggravating the other side right from the beginning.

I think that if a human starship ever encounters an alien ship, the first they will do is beam a signal back home if they can do so without giving away the position of human homeworlds. If something goes wrong, you want to have at least notified the rest of humanity of the encounter.

That is probably a good idea–unfortunately, I’m not sure how feasible it is to hide the star your originated from. If you left an obvious signature as you entered the system (as an antimatter or fusion engine is likely to do) I imagine that they could project your course back to get at least an idea of where you came from. But no studies have been done on this.

I recall a first contact story call All the Way Back by Michael Shaara in which vengeful aliens try to find the location of Earth from the logs of a murdered starship’s crew. They cannot, because the ever-paranoid humans had worked out a system of course-check coordinates which were fixed on Earth’s position and are not decipherable if you do not already know Sol’s position. For those who want to read the story, I found it here.

Well, I think this article focuses mainly on slower-than-light technologies that may someday be available to us, not purely speculative “warp drives”. So one assumption is that the encounter takes place at the destination system, without any easy means to “warp out”. Another assumption is that information can only travel at lightspeed, which means that if you stay off several lightyears you will see that alien yacht race as it was happening a few years ago!

So if we randomly come across an alien space party/yacht race/military exercise (or, heavens forbid, a space war) there probably won’t be any easy way to run away. But it is a good idea to halt in the outer system and observe carefully before coming in closer. Perhaps even ask for permission first, if we can establish communications.

I guess that I find it hard to visualize a need for a first contact protocol since I have a hard time believing that there will ever be a Star Trek type of encounter. It seems so far removed from how I imagine our civilization to function and value itself once we have achieved the point where our consciousnesses (biological or other) can leave our own solar system and interact with whatever is out there. When we have achieved that level of technological advancement, we will have little sense of scarcity, tribalism, patriotism, conflict, ‘other’, etc. I think that we often lose sight of the tight link that our culture’s values have to the current state of technology. That is, how we view others when we only have our limitations and insecurities to draw upon. When those limitations do not exist and we do not feel ‘threat’ as an option due to large-scale society redundancy, etc., (which I believe is a natural pre-cursor to leaving the solar system in all but the most limited ‘probe level’ of technology) then there is only the gathering of data as with all other gathering of data. I imagine that there would be some sort of marking and acknowledging of the event of realizing an interaction with another species, but I can’t see some kind of formal ‘relations’ as we have now between countries, etc. Such an advanced state of technology would render that quaint and frivolous, like a pre-1800s duel or a medieval marriage to seal a pact between kingdoms/fifedoms – a laughable anachronism. Further, to all of this is the idea that I cannot fathom an interstellar civilization being aggressive or even have a concept of a military or annexation as all scarcity has likely fallen with %-of-c travel; a most intensive use of resources. (Of course I am presuming that we do not visit a world of pre-interstellar travel, but meet (probably not a good word) with others who have interacted over the light years)

My point about Pi is that it is a simple relationship that can be passed on with images without knowledge of the species’ mathematical system. It can be passed on with simple images. The relationship between a circle and its diameter is universal in this spacetime continuum. If you have a species in a spaceship. they will have to have learned math, physics, etc. unless you believe in magic. If they are more advanced than we are they may have knowledge of forces, particles, etc. that we don’t but they still need the basic relationships to build and operate a ship. Math will provide the codex for communication.

Yes but Arithmetic and Geometry may be fundamental, but everything higher may be purely Homo-centric… whether there are other self-consistent “math”s out there in the cosmos is the question precluding using our human maths as the be-all-and-end-all for ‘obvious’ comms… our maths may be one of many.

Well, if there are species flying between the stars using magic–remember that any sufficiently analyzed magic is indistinguishable from technology!

Anthropocentric nonsense and jingoist fantasy. ET is almost certainly AI, and on a technological level exponentially beyond our own, and we will also be supplanted by AI ~100 years. Alien AI is almost certainly already aware of us and have quarantined us, ala the Zoo Hypothesis.

Are you familiar with the works of Hugo de Garis:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-cOipzmFhg

The main point here is about likely scenarios and these are a) far more advanced than us or b) far less advanced than us. The chances of “comparable to us” is vanishingly small. In both cases a) or b) the military should get the hell out of dodge on the entire contact scenario, because they have the potential to spell extinction for one species or another (us). I find it therefore ironic that a military person even has an opportunity to voice his opinion on the matter.

There is a certain irony there, usually the military get involved when it has all gone South or wherever South is in space. The military only get thrown in when the politians fail to see the error of their ways.

Human history, so it goes, was written by the victors of military conflict. That’s the legacy we have and that is all we have to analyze and determine how we might act differently when encountering extraterrestrials.

I appreciate the lively discussion and feedback from all – just what I was hoping for! Special thanks to Al Jackson and Michael Michaud, long time leaders in the field, for their comments.

There is a problem of unknowns and potential bias in this area, as I state, in that we only have our own planet’s history as a database to build from, so you have to make what you can of it. Perhaps at some point we can run AI through unconstrained evolutions such that we can get a totally independent viewpoint…

I do not think we should assume hostility on other civilization’s intent. That assumption heavily skews actions/reactions towards conflict and that is likely not to be to our advantage (for reasons multiple people have pointed out) – prudent caution seems likely to maximize options.

I think a survey of Science Fiction first contact scenarios would be a great Ph.D. dissertation topic for someone to work on. There is really good thought behind much (some?) of the work, and it would be well worth collecting – does anyone know if this has already been done?

With projects like Starshot and potential METI, now is the time to have this discussion.

I don’t know of any survey of SF contact-stories but if there is I would hope they include Babylon 5’s disastrous Minbari/Human first encounter… the Minbari ship opens its ‘gun-ports’ as their usual show of respect to a new race and of course we panic and open fire which sends us to the brink of extinction (kinda begs the question of whether the Minbari had previous problems using this approach).

In terms of hypothesizing a potential contact scenario between same-level contactees your article is very thought provoking. Personally, like a fair few here, I think this scenario is much smaller than the other alternative of contact between vastly disparate tech-levels and as we are likely to be the lesser level I think trying to instigate an overtly peaceful stance is essential. Eniacs “canoe” is a good example. As an optimist, I like to hope that any race at spacefaring level would’ve evolved through their agressive phase so as to be inherrantly peaceful… not learning this I think prevents ever getting to the point of startravel.

I suppose if they wished to stop and observe each other as they head towards each other they will have to both fire their engines at the same time or one of them dies from the exhaust of the other. If the engines are fired towards each other it would reduce the damage by a large factor, but it is then down to masses and velocities. It would be better i think to just go sailing past each other just to survive -without been rude of course.

I want to put my thoughts out there, and since this is the most recent related article, I’ll post it here.

There are many possibilities for contact with ETI. Are they hostile aggressors, saviors, or just like us? It seems like we project our own psychological needs onto aliens.

They may be incomprehensibly advanced, or as different from us as eusocial insect colonies.

One very common assumption is that ETI will be contemporary. It’s occurred to me that our first contact with ETI may be the discovery of ruins and artifacts left by a vanished civilization.

However it happens, contact with another intelligent race will change history permanently, for better or worse.

I for one cannot even begin to imagine the day when it hits the news “we are/were (archeological) not alone!”

I think the impact would be too great, our current society would not be able to handle it, there would be riots, mass suicides and an economical crash on a level never before seen.. And on top of that believing that we would be able to handle “the first contact” in a calm and intelligent way is putting too much hope in the human race.. Too many people aren’t even educated in the ways of science! First contact-even if its just archeological – wont be pretty.

Everyone has simply forgotten the factor of time…Assuming that travel about the galaxy is at sub light speeds, thousands of years will pass between single voyages, and cultures might die aboard ship long before arrival at a specific destination…That is true for electromagnetic communication…How can anyone envision a galactic civilization remaining intact when it will take thousands of years just to hear one tidbit of news from one global politician to the other…The arrow of time points forward and it is the answer to the Fermi paradox…There are many civilization out there but each is trapped by the distance between the stars…Let’s hope the Bell theorem is accurate…

Without playing the crackpot card… I do still think there may be some room to entertain the unlikely(?) possibility that, as clever as we are, there’s a bunch of physics that we are unaware of at present, and our opinions of what is and isn’t allowed will undoubtedly change over the next few hundred years or so. Maybe there’s a loophole we are unaware of that allows faster than ‘c’ comms? Never say never, perhaps?

For an interesting SF first contact I suggest the Star Trek next generation “Darmok” episode.

I think the contexts of first contacts will be different with FTL vs sublight. As someone wrote, sublight contact will most likely be at a destination, where the arriving sublight ship doesn’t have many options. In FTL encounters, protecting Earth’s location needs to be paramount until peaceful intentions are established. The existence of FTL communications will impact that scenario also. I wouldn’t count on the mythical idea that an advanced race must be benevolent. That’s more wishful thinking. The drive to get out into space requires an aggressive aspect. Just my opinion.

A

If they learn anything about us it would be prudent for a peer level civilization to launch a first attack on us as soon as possible knowing that we ourselves would attack without mercy as soon as it became beneficial for us.

In several thousand years of history human culture hasn’t changed all that much. Biblical Moses was willing to butcher entire races of people: men, women, and children put to the sword without hesitation – well, except for virgin women. Thousands of years later it’s still the same. Agent Orange in Vietnam that will poison the land, harming the people, for what we might as well call forever. When we couldn’t force N. Korea into a defeat bombing campaigns levelled the place, killing nearly a quarter of the people.

While a more advanced civilization might be able to sit back and wait, secure in their technology, the only hope of coexisting with a peer is a doctrine of MAD. As for any primitive cultures we might find, they would be useful for labor to help prepare a place for colonization, but then disposable.

Hopefully our first contact will be with a much more advanced culture; knowing we’re being watched might make us hesitate in our genocidal ways. We’d better hope though that that more advanced civilization isn’t into genocide itself.

As is often said, if current humanity can conceive of the following communications method linked to below, then imagine what a more advanced and more cosmically aware species might be able to do:

http://www.news.ucsb.edu/2016/016805/we-ll-leave-lights-you

http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2016/05/we-can-now-send-a-light-signal-across-the-universe-huge-implications-in-search-for-alien-intelligenc.html

To quote:

Imagine if we sent up a visible signal that could eventually be seen across the entire universe. Imagine if another civilization did the same.

The technology now exists to enable exactly that scenario, according to UC Santa Barbara physics professor Philip Lubin, whose new work applies his research and advances in directed-energy systems to the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI). His recent paper “The Search for Directed Intelligence” appears in the journal REACH – Reviews in Human Space Exploration.

“If even one other civilization existed in our galaxy and had a similar or more advanced level of directed-energy technology, we could detect ‘them’ anywhere in our galaxy with a very modest detection approach,” said Lubin, who leads the UCSB Experimental Cosmology Group. “If we scale it up as we’re doing with direct energy systems, how far could we detect a civilization equivalent to ours? The answer becomes that the entire universe is now open to us.

After “reading” Codex Seraphinianus, I think the 1st contact may be some kind of crackpot from the more advanced civilization; actually we might do the same if we encounter a lesser civilization in the future, the information in that book should take those lesser ET a long long time to decipher the nonsenses. Therefore, our encounter with more advanced civilization is more or less receiving the first interstellar troll on us. The scenario from “Story Of Your Life” comes to my mind when I think about this case, those in the military would love it!

““But we are peaceful and will not be going armed into space” you say.”

I don’t advise doing that. Every exploratory vessel that has the slightest chance of meeting anything alive larger than a rat should be armed to the teeth.

Music for Aliens: Campaign Aims to Reissue Carl Sagan’s Golden Record

By KENNETH CHANG

SEPT. 21, 2016

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/22/science/nasa-voyager-golden-record-carl-sagan-kickstarter.html

To quote:

“When you’re 7 years old, and you hear about a group of people creating messages for possible extraterrestrial intelligence,” Mr. Pescovitz said, “that sparks the imagination. The idea always stuck with me.”

Carl Sagan’s Intergalactic Mix Tape Could be Reissued on Vinyl

By Rachael Myrow

September 21, 2016

https://ww2.kqed.org/arts/2016/09/21/carl-sagans-intergalactic-mix-tape-could-be-reissued-on-vinyl/

To quote:

“This was intended as a gift from humanity to the cosmos,” Pescovitz says. “But it’s also a gift to humanity: a reminder of what we can do when we are at our best. That reminder is perhaps more necessary and relevant today than it was even then.”

…

“This was one of the more utopian endeavors of humanity,” says Azerrad, noting the golden record left out the ugly bits of human experience, like war and famine. That may have something to do with the record’s enduring appeal.

“In a lot of ways, it embodies a type of thinking much harder to find in today’s world. We’ve kind of lost that aspiration to look at who we are as a human race.”