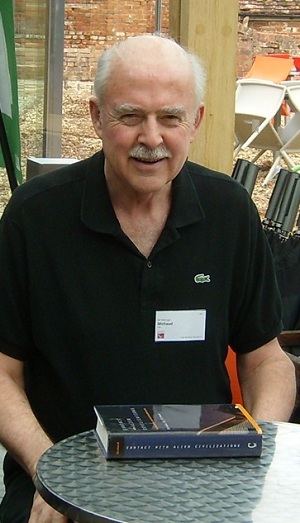

When we contemplate contact scenarios between ourselves and extraterrestrial civilizations, we can profit from remembering our own history. The European arrival in the Americas is often a model, but there are other events of equal complexity. In the essay below, Michael Michaud looks at America’s encounter with Japan to examine how we might react to a civilization not vastly more advanced in technology than our own. A familiar figure on Centauri Dreams, Michaud is now retired from an extensive diplomatic career that took him from director of the U.S. State Department’s Office of Advanced Technology to chairman of working groups at the International Academy of Astronautics that discuss SETI issues, along with posts as Counselor for Science, Technology and Environment at U.S. embassies in Paris and Tokyo. He is also the author of the seminal Contact with Alien Civilizations (Springer, 2007).

By Michael A.G. Michaud

In the literature about possible future contact with an extraterrestrial civilization, one of the most familiar presumptions is that the aliens will employ technologies vastly more advanced and more powerful than our own. Hollywood has given us binary images of such technologically empowered beings, depicting them as either benign altruistic teachers or as monsters who want to destroy us. There is a lot of room between those extremes.

A countervailing theory suggests that we are most likely to encounter a technological civilization closer to our own level, as the most advanced would ignore us or treat us as irrelevant. What might happen if we came into direct contact with a civilization whose technologies were only a century in advance of ours? Here is an Earthly example.

In 1852, U.S. President Millard Fillmore assigned U.S. Navy Commodore Matthew Perry to force the opening of Japanese ports to American trade. Perry was to deliver a letter from the President to the Emperor of Japan.

At the time, the only authorized port of entry into Japan was Nagasaki, where the Dutch maintained a trading post. The Japanese, forewarned by the Dutch that Perry’s ships were on their way from the United States, refused to change their 220 year old policy of exclusion.

Perry’s mission to Japan was part of a much longer voyage around southern Africa to Asia, a showing of the American flag. After an eight month journey with multiple port calls, Perry’s squadron of four ships reached the entry to Edo (now Tokyo) Bay on July 8, 1853.

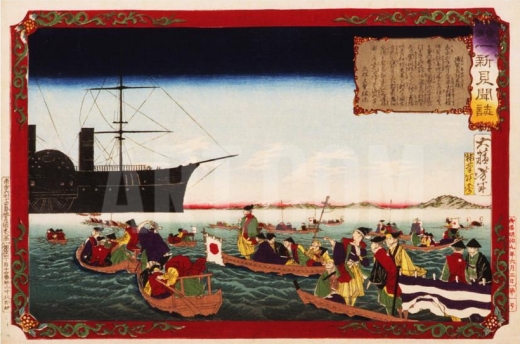

Numerous Japanese fishing boats hastily retreated from the American ships, whose crews were at battle stations. Perry’s account reports that the fishermen seemed astonished to see the steam powered American vessels proceed against the wind with their sails furled.

Japanese officials in boats approached the American ships several times, asking them to leave. The first boat bore large banners with characters inscribed on them. The Americans, who could not read Japanese, conjectured that this boat was a government vessel of some kind.

Another Japanese boat approaching the American ships carried a man holding up a scroll which he read aloud. He was admitted aboard to meet with a lower-ranking American officer. The scroll, later found to be a document in French, conveyed an order that the American ships should leave, reiterating that Nagasaki was the only place in Japan for trading with foreigners.

The crews of Japanese “guard boats” made several attempts to board Perry’s ships, but were repelled by Americans with pikes, cutlasses, and pistols. No casualties were reported.

Image: American Navy Commodore Matthew Perry arrives in Japan, August 7, 1853. Credit: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, woodblock print.

Through his officers, Perry warned that he would not permit Japanese guard boats to remain close to his ships. If they were not immediately removed, he would disperse them by force. When a few guard boats remained, Perry sent armed men to drive them away.

The Japanese made token shows of force on shore, firing out of date cannons and launching rockets. None seemed to be aimed at the American ships.

Perry warned the Japanese that, if they chose to fight, he would destroy them. In a demonstration of force that did no physical harm, he ordered blank shots to be fired from his squadron’s 73 cannons.

The Americans discovered that Japanese defenses were more for show than combat. Using a telescope to observe forts on headlands, they found some in an unfinished state. Screens had been stretched in front of the breastworks, possibly with the intention of making “a false show of concealed force.” The narrative’s writer observed that the Japanese had not calculated on the “exactness of view” afforded by a telescope.

Perry strove to impress the Japanese with “a just idea” of the power and superiority of the United States. He described his demands as “a right,” and not an attempt to solicit a favor. He expected “those acts of courtesy which are due from one civilized nation to another.” If the Japanese assumed superiority, that was a game he could play as well as they.

Perry refused to meet with lower level Japanese officials. His narrative observes that the more exclusive he made himself, and the more unyielding he was, the more respect “these people of forms and ceremonies” would award him.

A Japanese man who was described as a Governor came to Perry’s flagship, where he met with American officers while Perry remained invisible. (The visitor actually was the Deputy Governor.) At one point, lower ranking American officers dealing with the Japanese elevated Perry’s rank from Commodore to Admiral.

As one might expect, language was a problem. The Americans had one interpreter who knew Chinese and another who knew Dutch, but no one who spoke Japanese. The Japanese provided an interpreter who spoke Dutch; the two sides used a third country’s language.

The Americans warned that if the Japanese did not appoint a suitable person to receive the President’s letter and other documents from the American capital, Perry’s forces would go ashore with sufficient force and deliver them in person (by implication, to the Emperor). They pointed out that that one hour’s steaming would bring Perry’s ships in sight of Edo (Tokyo). Perry did send one of his ships closer to Edo, anticipating that this would alarm the Japanese authorities and induce them to give a more favorable answer to his demands.

When Perry sent out boats to survey the coastline, Japanese vessels carrying armed men rushed toward them. The American officer in charge of the surveying party gave orders for his men to arm their weapons. Seeing the armed sailors, the Japanese avoided a direct confrontation.

At last, the real Governor visited Perry’s ship, exhibiting a letter from the Emperor that met Perry’s demand for a high level Japanese official to accept the letter from the American President. The Governor provided the Americans with a copy in Dutch.

Arrangements were made for a ceremony on shore. Japanese officials asked Perry to move his ships close to a beach in modern day Yokosuka (where there is now an American naval base). There he would be allowed to land.

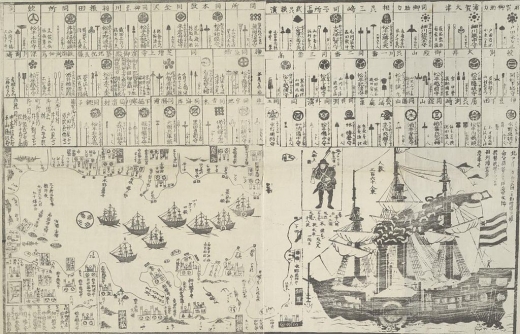

Image: Japanese 1854 print describing Commodore Matthew Perry’s “Black Ships.” Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Perry’s approach the next morning was announced by American guns. In a formal ceremony under a large, decorated tent, he presented the documents from Washington. He promised to return the following year to receive the Japanese reply.

Perry commented in his report that the Japanese officials showed a quiet dignity of manner and never lost their self-possession. However backward the Japanese might be in practical science, he wrote, the best educated among them were “tolerably well-informed of progress among more civilized nations.” Perry expressed a hope in his account that “our attempt to bring a singular and isolated people into the family of civilized nations may succeed without resort to bloodshed.”

Perry returned to Japan in February 1854 with ten ships and 1,600 men, putting even more pressure on the Japanese. After initial resistance, he was permitted to land at Kanagawa, near present-day Yokohama. A month of negotiations led to the first Convention between Japan and the United States.

The American negotiator on the spot had greater latitude in that pre-radio era, when communication with capitals was slow. Unfortunately, Perry was mistaken in his belief that this agreement had been made with the Emperor’s representatives. He did not understand the position of the Shogun, the de facto ruler of Japan.

What lessons can we draw from this? Most obvious is that finding a shared language would be difficult. Points might be made through actions or images rather than words.

Another lesson is that this meeting of technological unequals did not lead to armed conflict. The Americans used their superior weapons and propulsion technologies to intimidate, not to damage or conquer. Despite their threats, they acted with restraint, and got their way without violence.

The Japanese, though making only weak shows of force, insisted on being treated as diplomatic equals through rituals and symbols. The Americans, as the more powerful civilization, maintained a balance between intimidation and respect.

We may want to keep histories like this in mind as we weigh possible contact scenarios. Contact may not be between cultures separated by millennia of scientific and technological development.

Readers interested in a complete account of this event may wish to look at Commodore M.C. Perry, Narrative of the Expedition to the China Seas and Japan, 1852-1854, reprinted by Dover in 2000. As Perry’s visit took place in the pre-photographic age, that report was illustrated with lithographs and woodcuts by American on-board artists.

Excellent!

It’s a very good point that “take me to your leader” can be a disruptive effect for a group that doesn’t have any single leader. In Japan’s case, there were certainly two leaders: the Shogun and the emperor. This caused a great deal of turmoil in Japanese society and led to the end of the Shogunate. Perry had no idea what effect would have on Japan.

We shouldn’t think that Perry’s actions reflected the USA. A different expedition leader might have reacted very differently.

Similarly, suppose the Japanese acted more like the Hawaiians who killed Cook. Then what might have happened?

The assumption of the story is that the travelers (Humans in star ships) would be more technologically advanced than the locals. What is that isn’t true? Japan may have been as relatively advanced as China when the Europeans arrived to trade with China. What if Japan had proven more advanced than the US in the mid 19th century? Would the outcome have been very different as Perry’s show of force would have proven futile in the face of superior technology.

Perry was lucky to have found common ground with language. This will not be the case with aliens as there will be no prior contact, unless earlier observation cracked the language. But what if alien communication modes are very different from ours, then what? We might need both observations and a need to use avatars that can interact with locals using their communication modes, or we use machines to aid “face to face” communication.

Again, Perry was dealing with fellow humans, with a shared biological ancestry and human types of organization (hierarchies reflecting primate groups). How do we deal with organisms with very different evolutionary paths that have very different social systems?

I suspect all human contact stories will look like simple events compared to real alien contact. That might take generations or more to achieve. certainly not a short stay with a “shore party”, before returning to the ship and on to the next planet.

The Hawaiians actually did not act aggressively towards Cook. Relations were good for a long time, until one unfortunate incident. Some Hawaiians stole a boat (or were accused of it, at least), whereupon Cook attempted to kidnap their king for ransom. It was then that Cook was killed, in defense of the king. So, I suppose if Cook’s men had been more careful watching their boats, or less aggressive about confronting the natives about the theft, the visit could have been a peaceful and productive one. Like the many others Cook made on his voyages without getting killed.

If the arriving party were to be technologically inferior, they could simply be repelled by show of force, or taken into custody. A violent confrontation is only likely when both parties feel they have a chance at winning. For that to be the case, the arrivals must be technologically superior to the natives, who have the advantage in logistics and numbers.

“A violent confrontation is only likely when both parties feel they have a chance at winning. For that to be the case, the arrivals must be technologically superior to the natives, who have the advantage in logistics and numbers.”

Just what happened when Cortez landed in Mexico. He had an unanticipated edge because the Indians expected their god Quetzalcoatl to return that year; their hesitation let him arrive at their capitol while another conquistador, Narvaez, arrived in Mexico carrying smallpox.

The lesson? He who hesitates is lost.

Japan had been in contact with Europe since the late 1500s. By the 19th century it had an agency whose job was keeping track of Western military and political developments (IIRC the agency was called the Center for Barbarian Studies or something similar). So Perry’s arrival was not really a first contact, and as noted in the post the Japanese already had some information about what they were dealing with.

As another distinction, the Japanese also generally were aware that there were other humans on other continents. They apparently just didn’t want to have much of anything to do with them (perhaps wisely).

In contrast, an alien culture may not yet have had it confirmed — even if they perhaps suspected — that there was other sentient life in the universe. That might be a fairly large revelation to absorb in one sitting at a first contact.

That prospect tends to lend further support to Alex’ suggestions of possibly making first contact remotely/indirectly and also going slow, after conducting as much prior observation as possible.

One hopes and trusts that, if we were the contacting culture in such a future scenario, we would be “a bit” less insistent than Perry was for mid nineteenth century America.

Very interesting, thank you. You’ve reminded me a book, “Encounter with Tiber” by Buzz Aldrin/John Barnes. They present an excellent juxtaposition of both space and time and the consequences of technological and cultural differences.

As a biologist/chemist I always try to encourage the ‘Hardware types’ to reflect more on advances in the lesser sciences. By the time we are sending a few grams of payload across lightyears, we will most probably have spun off new intelligent “life” forms of similar mass (if we can muster the ethical courage to do so).

In the fullness of time, it could all come together without the need to send massive H. sapiens off shore at all. Maybe

A difference of millennial would be a best case scenario. It is more likely that any alien civilization(or its remnants) would be apart from us by hundreds of millions of years.

While the story about Perry’s expedition is well known, we usually are far less aware of the that Japanese have sent in 16th and 17th century their own expeditions to explore the world, including an amazing journey through Americas to Europe.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tensh%C5%8D_embassy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hasekura_Tsunenaga#Mission_to_Europe

Didn’t Perry’s mission to Japan sow the seeds for later warfare between the US and Japan?

No it didn’t. Japan’s started the war with the USA by bombing the USA.

Viewed narrowly, sure. But each event in history has preseeding causes. Japan at the time of Perry’s contact mission was xenophobic. They were bullied into opening up. Would they have built up their millitary as fast as they did if this contact had been less forced?

My point is simply to learn from history.

One leason

That’s the naive view. America forced Japan to become a modern industrial society which ultimately led to WW2. Our second big mistake was bringing feudal Middle Eastern societies into the modern world of technology.

Not really a mistake, really, as we would not have been able to stop it. Technology quickly spreads everywhere. Attempts to close oneself off, as the Japanese did back then, or attempts to withhold technology from others are doomed in the face of trade.

Remember that this was in an environment in which seemingly every land in Asia was being colonized and exploited ruthlessly by European states.

Recall Japan beat Russia’s navy in their 1904-5 war, so the USA WWII war came from Japanese expansion policies.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russo-Japanese_War

Japan was forced to go to War with the USA as a result of its alliance with Germany. The US policy of squeezing the Japanese economy by restricting key commodities in response to the Japanese invasion of China and SE Asia helped push the events along.

The Japanese policy of expansion was a result of the Meji Restoration which modernized Japan as a direct result of Perry’s contact. Western powers’ control of Asia and policies towards Japan may have exacerbated Japan’s militaristic approach.

Is there really any doubt that Perry’s visit was the initial stimulus that led to Japan’s involvement in WWII?

The Japanese/German alliance did not require either country to go to war if their ally took the offensive. Germany attacked Poland in 1939, and Japan did nothing. When Japan attacked the US in 1941, Germany declared war voluntarily, not because of any treaty obligation.

Japan initially embraced Western approaches, down to treating its Russian POWs honorably in 1905. It was the later Japanese militarists who shifted the country into mad-dog mode that prevailed through WWII.

We aren’t guilty of everything wrong with the world. It’s time people gave up that carefully taught and cultivated bit of self-hatred.

Japan didn’t HAVE to attack us they decided to for their own reasons, like a desire to attack other Asias without risking our helping our allies.

Nepal was brought into contact with the modern world in the 1800s and didn’t attack anybody. Same with Sumatra.

It depends on the resident culture and political system. Other peoples than the US have their own distinct cultures and historical motivations. They aren’t merely reacting to us. They’re complicated, too.

Reforming that attitude will help us speculate about alien contact, though they will likely be far more different than Earth cultures we’re familiar with.

The moral of the story: when dealing with judeao/christian/islamic nations build lots and lots of weapons. The best that you can, and never hesitate to use them. It will be the only way to maintain your freedom, perhaps your very life.

Are there any stories of contact between two groups of humans that doesn’t contain violence. And yes I call sailing a fleet halfway around the world, into another nation’s waters, and threatening acts of war violence. In all of human history is there even “one” such story?

It depends. There were many peaceful encounters (Cook’s voyages, for example, or the Thanksgiving pilgrims), but eventually, given enough encounters there will be violence. The fact is, you don’t need “first contact” to get violence. There is plenty of violence between groups that know each other well.

I suppose the real question is the frequency of violence greater in encounters of vastly different cultures than in the encounters of subgroups of the same culture? I don’t have a clue. Could be either way. That would be worth a rigorous historical study, if you can keep it unbiased.

There is some species that always enjoy playing non-zero sum games independent of contact process, the goal of ruling over the entire galaxy is an elementary example. Anyway, contact between two civilizations which belong in the same level is extremely rare, the spatial and temporal differences make sure the advanced ones decide rules of the game, just exactly the way those isolated people from New Guinea or Brazil have zero saying in region above 500 km from the surface of this planet.

Yes Japan opened up and really was an advanced country by WW 2. They felt they needed more resources and accused us of getting in their way. We really cheered them on in the Russo Japanese war. We have not fought a major war with a major power since WW2. The Europeans did encounter some near equal civilizations inbthe Americas but European diseases destroyed them before there were major clashes….in Sci fi we survive because the more advanced Martians die of our diseases. Btw something we must be very careful of in Mars exploration. So we dont contaminate Mars or vis versa

Aliens might be indifferent to other life forms. I don’t mean this idiotic notion they’ve already seen and don’t like us (based, of course, on our own values), just that they might be unconcerned.

If there’s no territorial strife there might be little trouble.

Odd if they started imitating us. Not mockingly, just imitating down to surgically altering themselves to resemble us as well as giving their imitations of our behavior. Not as in a cargo cult in hopes of acquiring our technological advantages if any, just imitating. Or incorporated some elements of our culture for some to us inexplicable reasons — if Abbott & Costello TV shows from the 1950s became a dominant interest of theirs, for example.

They’re aliens, after all.

Indeed, 88 years later Japan attacked the US, even though the best informed among them understood this would be suicide.

… and what followed in Japan was an astonishing, rapid modernisation, wherein a feudalistic, agrarian people would in under 50 years take on a modern power, Russia, in open warfare and defeat them.

I had a cat that used three words, vocalized so that visitors recognized them: Milk and Out as request, and calling my name when distressed. I have a dog that understands hand signs, the difference of my future actions depending on which shoes I put on, and understands the specific meaning of the tonal quality of my voice, and has her own gestures to request out, food, and play. These animals and I share a remarkably similar biology. Alien life will not share near as much physically and certainly not as much intellectually and emotionally. We will be viewed either a threat to be eliminated or a curiosity to be studied, much as a snake is viewed by human beings.

Makes sense. They might not have emotions unless that’s a general term for internal states motivating or accompanying situations/actions.

We’ll just have to wait to find out, and naturally different aliens will be as different from each other as from us.

Hmm, we have a lot which can be learned from past encounters. I think it is more likely that humanity will wind up being the more advanced civilisation in a first contact, as it is very likely that the heyday of life in the universe is not now, but in the distant future.

Low chance of finding an less advanced civilization, civilization is perhaps 7000 year old, before that its stone age for an million.

So either we find something stone age or somebody more advanced than us.

My joke take on first contact http://i.imgur.com/QNnA8iM.png

Yes, I would bet on a some kind of contact with a hunter-gatherer type society late in the 22nd century at the very earliest. That’s assuming we have FTL by the year 2100, which I am quite confident of.

Of course its possible that we detect some kind of signal before then, but if this is the case, chances are that it is from very far off and so is a one-sided contact. Even assuming a top speed of 10C (Harold White, Eagleworks), it is likely to be a very long time before contact with a similarly or more advanced civilisation.

Unless we get or aliens has an faster than light drive an first contact is likely to be an signal or an robotic probe. In short it will be slow as the robot explorer is likely to have low authority.

This works both ways, both for us and aliens.

Although not “first contact” stories, Kathryn Rusch Disappeared stories often hinge on humans doing something unintentionally awful/illegal to a nearby alien race. We may have similar problems, blundering into situations that seem innocuous to us but are transgressive to the alien culture.

In that sense, Start Trek has it right. Observe aliens from “hides” until you understand enough to make contact. Fossey was careful in her observations of mountain gorillas before exposing herself to them. But in both cases, the creatures are close to human (the aliens can be understood in human terms.) Truly alien creatures, like those depicted in the movie “Arrival”, may be much harder to understand, and possibly not understandable.

If the galaxy does have a number of relatively advanced species, it may turn out that some are understandable to humans while others remain incomprehensible. Which we encounter first may just be chance.

Close contact with apes was carefully thought out by Dr. Leakey. He wanted women to do it because he knew the male apes would see male humans as sexual rivals and female humans as harmless. Most mammals can tell the sexes apart in other species and conceptualize them in their own mating scheme.

We won’t have even that much knowledge about aliens.

I did not know that, but it makes sense. Our sense of smell is very limited compared to other mammals generally, and primates. Women are far less likely to induce male dominance displays and fighting, and of course, humans are far weaker than chimps, let alone gorillas.

Seems that the nature of universal intelligence comes first…That is.. aliens go through the same discoveries as humans do…atomic structure is the same everywhere…near and far…maybe the territorial imperative works in every spacefaring civilization as it works on earth…fright or fight or flight…but in sub-light travel an alien probe coming here might take 1000’s of years en-route…just to satisfy their curiosity? This time difference between send-off and arrival is rarely accounted for in terms of an alien motive…are they interested on our oceans…or in brotherhood…or what? Hugely popular science fiction seldom deals with this time problem…fantasy is preferred…bending space and so forth and so on…

A few months ago, I posted an analysis about aliens in popular culture. I categorized their various incarnations as Savior, Destroyer, and Mysterious Other. Those interested can read it here: https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=36714 scroll about two-thirds of the way down.

What these very different archetypes have in common is that they are psychological projections, which do not necessarily have any concordance with ETI that may be out there.

Alien contact is a momentous occasion for both parties, as we’ve seen in history. The exchanges, conflicts, shocks and paradigm shifts are significant enough between two different civilizations of the same species — these effects would be greatly magnified in the case of contact between different intelligent species.

I believe there would be profound differences, but also some common ground. Intelligent aliens are highly likely to be social and capable of aggression. Biochemistry, energy requirements, evolution, the need to survive and reproduce, and the constraints of living in this universe would shape them just as they shaped us. However, even the most radically different human civilizations still operate within particularly human constraints, which do not apply to ETI. It is unlikely that the language barrier between us and ETI will be broken with any ease or quickness, if at all — on the other hand, every human language can be translated, albeit imperfectly.

To draw another historical parallel, civilizations do not just meet in space, but through the dimension of time. The Greco-Roman world, Ancient China, Feudal Japan, Medieval Europe, et al. influence us today although we are not their contemporaries. It is entirely possible that when we meet ETI, it will be in the form of ruins and artifacts of a vanished race. This would also have a profound impact on us, although not in the same way as contemporaneous contact.

“Will China Be the First Nation to Discover Advanced Alien Life?” (WATCH Today’s “Galaxy” Stream)

March 5, 2017

This past September, China put on the “ear phones” and flipped the “ON” switch for the world’s largest, most powerful radio telescope nestled in a vast, bowl-shaped valley in the mountainous southwestern province of Guizhou. The unrivaled precision of the FAST telescope will allow astronomers to survey the Milky Way and other galaxies and detect faint pulsars, and work as a powerful ground station for future space missions. With a dish the size of 30 football fields, FAST, which measures 500 meters in diameter, dwarfs Puerto Rico’s 300-meter Arecibo Observatory. Under new regulations, FAST requires radio silence within a 10-kilometer radius.

“Having a more sensitive telescope, we can receive weaker and more distant radio messages,” Wu Xiangping, director-general of the Chinese Astronomical Society, “It will help us to search for intelligent life outside of the galaxy and explore the origins of the universe,” he added underscoring the China’s race to be the first nation to discover the existence of an advanced alien civilization.

Full article here:

http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2017/03/will-china-be-the-first-nation-to-discover-advanced-alien-life-todays-galaxy-stream.html

To quote:

FAST is the world’s largest single-aperture telescope, overtaking the Arecibo Observatory in the US territory of Puerto Rico, which is 305 meters (1000 feet) in diameter. The dish will have a perimeter of about 1.6 kilometers, Xinhua said. According to chief scientist from China’s National Astronomical Observations, Li Di, FAST is able to scan up to twice more areas of the sky than Arecibo, and it will have between three to five times the sensitivity. It’s in their hopes that if there is indeed alien life, this gargantuan will find it.

“A radio telescope is like a sensitive ear, listening to tell meaningful radio messages from white noise in the universe,” said Nan Rendong, chief scientist of the FAST project. He told Xinhua that the huge dish enables much more accurate detection. “It is like identifying the sound of cicadas in a thunderstorm.”

The Chinese government hopes that a more subtle benefit of the behemoth eye on the cosmos will entice some of the some of the brightest minds in science or astronomy studying abroad to return home to China. China is the leading nation in the world in the number of students it sends students abroad, especially for majors such as science or engineering.

For years Chinese scientists have relied on “second hand” data collected by others in their research and the new telescope is expected to “greatly enhance” the country’s capacity to observe outer space, Xinhua said. Beijing is accelerating its military-run multi-billion-dollar space exploration program, which it sees as a symbol of the country’s progress. It has plans for a permanent orbiting station by 2020 and eventually to send a human to the moon.

The Daily Galaxy via AFP/Beijing