Is there something about human beings that ensures we will always explore? I think so, even while acknowledging that there are many who have chosen throughout history not to examine potential frontiers. The choices we make on Earth will be reflected in our future beyond the Solar System, assuming there is to be one. Nick Nielsen looks at these questions in a historical context today, seeing history as a fractal structure, but one whose future is not clear. A path that can lead to the stars as our destination is available in what he describes herein as a new stage of growth not limited by a single world and large enough to contain projects on a planetary scale. When he’s not writing for Centauri Dreams, you can follow Nick’s work on Twitter @geopolicraticus or on his blog Grand Strategy: The View from Oregon.

by J. N. Nielsen

The human condition: questions and answers

What is perhaps Paul Gauguin’s best known painting —D’où Venons Nous / Que Sommes Nous / Où Allons Nous [1] — depicts a panorama of the stages of human life against the backdrop of the ordinary business of life on Gauguin’s adopted home in Tahiti. The questions that Gauguin painted into the upper left corner of this painting — Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? — are as relevant as ever, but how we answer them, or how we attempt to answer them, has changed over time. In the past, mythological answers sufficed, partly because mythology presents the human condition in concrete and intuitively tractable forms [2] and partly because there was no other conceivable form for the answers to such far-reaching questions to take. Today, however, we can conceive of a non-mythological approach to answering the perennial questions of human nature and the human condition.

Possibly for the first time in human history we are in a position to offer scientific answers to the perennial existential questions of the human condition, and this, I think, is all to the good. Mythology will always play a role in human life, but there as yet exists no mythology that has grown out of our industrialized civilization, and consequently no mythology that is adequate to understanding this civilization or to understanding our place within this civilization. If we are going to understand ourselves on our own terms, on terms familiar to the world we have built for ourselves with science, technology, and engineering, we are going to have to understand ourselves through science.

Where we’ve been

“Where do we come from?” is now a question of history, and particularly of scientific historiography that has expanded far beyond the history of humanity as documented in written sources, drawing upon biology, paleontology, anthropology, archaeology, and a dozen other disciplines which, when integrated, give us comprehensive overview of the origins of human beings.

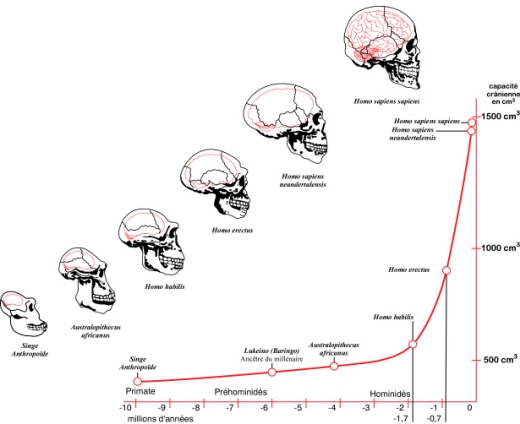

Human history, if extended to the origin of our species, comprises more than five million years, that is, more than five million years since the last common ancestor of humanity and the other primates. Very little happened during several million years of increasing encephalization and virtually unchanged stone toolkits. But if you were to look at human history as a graph of several parameters used to quantify and measure intelligence and intelligent activity, from a distance this graph would look like an exponential growth curve, being first of all the curve defined by human encephalization. [3]

If you move in closer to this graph, instead of looking at millions of years, looking at the tens of thousands of years elapsed since anatomical modernity (after encephalization attained modern levels) and cognitive modernity (when that encephalization began to express itself in distinctively human forms), once again the graph would look like an exponential growth curve, with the initial wave of technological and artistic expressions of the upper Paleolithic—painting, sculpture, music, more sophisticated tools of bone, and flint and obsidian industries that truly can be called “industries.”

If we look even more closely, at the last few thousand years, once again we see an exponential growth curve, as humanity settled the planet entire and civilization itself began, quantified by the number, diversity, and density of human settlements. And finally, if we look at a scale of only a few hundred years, once again we see an exponential growth curve (especially in the human population, due to reduced morality as a result of better nutrition and scientific medicine) as industrialization and then electrification dramatically changed the world in which we live.

You will already have guessed what I am suggesting: human history is a fractal in which there is a self-similarity across multiple scales of historical magnification. If this fractal structure of human history is extrapolated into the future, further exponential growth is implied. But what form could future exponential growth take? The instances I have mentioned have ranged from physical anthropology through cognitive modernity to social organization. It would be difficult to reduce these instances of exponential growth to a single class, except to note (as has already been noted) that all have been manifested in human history, therefore all are, in a sense, a function of the human mind.

The past testifies to the fractal structure of human history, but the future of this fractal structure is not at all clear—not even what human capacities or activities might be involved in future exponential growth—nor is there any certainty that this pattern will continue. Of the fractal structure of human history, all that we can say at present is that this is where we have been and this is what we have done as a species. It is an unprecedented history in the context of all life on Earth, and inductively this suggests an unprecedented future, but inductive arguments are probabilistic rather than certain and apodictic.

Where we are now

“What are we?” Where we are now is a function of what we are, and what we are is a function of our history. As we have seen above, scientific historiography can provide us with an overview of the expanses of human history previously closed to us when our only source of history was derived from written documents. While the selection pressures that act upon us over the longest time scales made us what we are today, human beings have changed the environment in which humanity lives (a process known in ecology as “niche construction“) and in so doing have reflexively subjected themselves to selection pressures of their own making. Chief among these human selection pressures is the large-scale social organization that we call “civilization.”

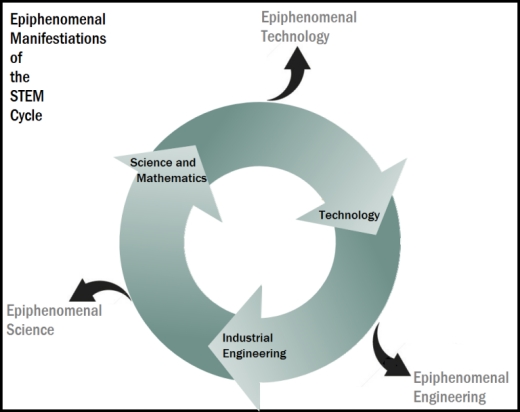

The civilization that we have today has been called by many names; I call this kind of civilization “industrial-technological civilization,” and it is uniquely characterized by a positive feedback cycle (which I call the “STEM cycle“). Science seeks to understand nature on its own terms, for its own sake. Technology is that portion of scientific research that can be developed specifically for the realization of practical ends. Engineering is the industrial implementation of a technology. Moreover, industrial technologies can be used to produce better scientific instruments, yielding yet more scientific knowledge and driving the cycle forward. Mathematics is the common language that connects the elements of the cycle and integrates them in a tightly-coupled structure.

Science produces knowledge, but technology only selects that knowledge from the scientific enterprise that can be developed for practical uses; of the many technologies that are developed, engineering selects those that are most robust and reproducible to create an industrial infrastructure to supplies a mass consumer society. The achievements of technology and engineering are in turn selected by science in order to produce novel and more advanced forms of scientific instrumentation, with which science can produce further knowledge, thus initiating another generation of science followed by technology followed by engineering.

In some cases the STEM cycle is only loosely-coupled. The resources of advanced mathematics are necessary to the expression of physics in mathematicized form, but there may be no direct coupling of physics and mathematics, and the mathematics used in physics may have been available for generations. Pure science may suggest a number of technologies, many of which lie fallow, with no particular interest shown in them. One technology may eventually come into mass manufacture, but it may not be seen to have any initial impact on scientific research. These episodes can only be understood as part of a loosely-coupled cycle when seen in the big picture and over the long term.

In this loosely-coupled sense, all civilization could be said to be characterized by the STEM cycle.

What distinguishes civilization today is an increasingly tightly-coupled STEM cycle in which incremental but continuous advances in science, technology, and engineering are predictable, and in some cases can be systematically pursued. In a highly specialized way, the R&D departments of large business enterprises comprise the entire STEM cycle, as applied to a particular problem or some particular aspect of human experience, within a single institution. We can, in other words, engineer the STEM cycle itself in order to maximize (or to specialize) its productivity of scientific knowledge, technological innovation, and industrial engineering.

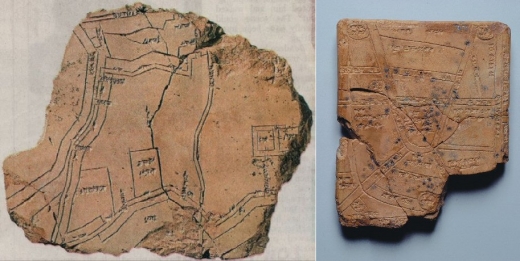

Image: City planning in the ancient world.

How we got to where we are now

We got to where we are today, in terms of our civilization, by the tightening of the STEM cycle from a loosely-coupled cycle to a tightly-coupled cycle. The inflection point of this tightening was the industrial revolution, which resulted in a new kind of civilization as the consequence of a sudden and rapid tightening of the STEM cycle. But this is only the latest iteration of civilization, the entire history of which (like the fractal history of humanity on the whole) exhibits numerous inflection points beyond which human life was rapidly transformed.

The most remarkable feature of how we got from the origins of our species to the complex and sophisticated civilization we have today is that, with few exceptions, none of it was planned. Technology was not planned; civilization was not planned; industrialization was not planned; the internet was not planned. These things all happened, and they might just as readily have happened otherwise; any survey of history is strewn with obvious counterfactuals, i.e., paths not taken.

Certainly it can be said that individual projects undertaken by individuals, institutions, and in some cases entire communities have been carefully planned and systematically executed. The first cities of our earliest history were not planned, but urban planning rapidly emerged in antiquity and now the planning of cities—arguably, the centers of civilization, and the existence of which is sometimes taken by archaeologists to be the defining marker of civilization [4]—is routine. While individual cities may be planned, the overall historical structure of urbanization has not been planned, nor is it planned today; no one planned that humanity should become a majority urban species. The great movements of human history, built up from the collective but uncoordinated actions of billions of individuals living and dead, were not planned, and still elude planning.

Nineteenth and twentieth century attempts to create planned communities (to say nothing of planned civilizations) on a utopian model were almost all dismal failures. Utopian dreams were almost without exception transformed into dystopian nightmares, and the practice of community never coincided with the theory of community. Moreover, even the great unplanned movements of human history also eventually came to grief. Civilizations, cities, and the great works of humanity have been painstakingly constructed only to be abandoned or thrown down in great wars and violent convulsions of history.

Civilization has stumbled many times in human history, and this is due in part to a failure to understand what civilization is, which has meant the absence of purposeful, knowledge- and evidence-based intervention in history to sustain and grow civilization. We have gotten by, as Kenneth Clark said, by the skin of our teeth. [5] We cannot count on being lucky indefinitely. But, as we have seen, civilization appears resistant to planning. We have not yet been able to understand (let alone effectively intervene in) the basis of our own large-scale social cooperation.

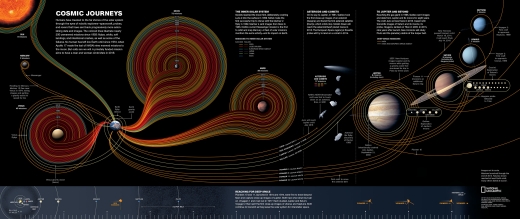

Image: Our journey into the cosmos starts by following the lead of our robotic probes.

Where we need to be

If we value the goods human beings have produced throughout our history, if we find in the artifacts of human civilization goods of intrinsic value worthy of preservation [6], then we ought to take action to secure the blessings of civilization for ourselves and our posterity—or for any other sentient-intelligent species that might come to appreciate the unique intrinsic values produced by human civilization. [7]

As a civilization, we need to be in a position in which we can ensure the continuing growth of knowledge, the establishment of multiple independent centers of civilization, and the autonomy of these distinct centers of civilization in order that social and political experimentation is maximized in order to secure for humanity the implementation of the broadest possible range of strategies for existential risk mitigation. [8]

At the stage of development of civilization that we have today, this means ensuring the continuation (if not the acceleration) of the STEM cycle, while extending our civilization across as many gravitational thresholds as our increasing technology allows us, i.e., passing beyond an exclusive reliance on Earth and becoming what Elon Musk has called a “multi-planetary species.” For beings such as ourselves, becoming a multi-planetary species is predicated upon becoming a spacefaring civilization, because it is only through spacefaring that we will reach other worlds.

Firstly we need a human presence in Earth orbit beyond the International Space Station (ISS), then a human presence throughout the solar system, then a human presence beyond the solar system. Each of these steps for spacefaring civilization is the overcoming of a gravitational threshold, much as our now-ubiquitous air travel overcame the topographical (and gravitational) threshold of seas and mountain ranges and the challenge posed by distance. With each gravitational threshold we transcend we gain a new opportunity for the redundancy of our civilization at an ever-greater distance from our homeworld (which entails proportionally greater independence and autonomy), as well as acquiring technological abilities that can contribute to the success of these independent centers of civilization and to the continued outward expansion of independent centers of civilization on the farthest frontier brought within our technological capability.

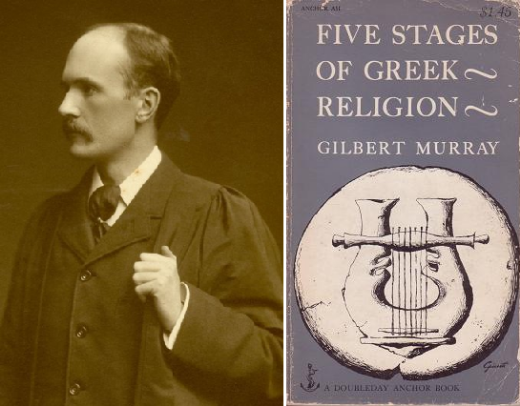

Image: Gilbert Murray and his classic study Five Stages of Greek Religion.

What are the obstacles to getting where we need to be?

The current consensus that appears to be emerging is that the greatest existential threat to humanity and human civilization is what may become of artificial intelligence, especially in the form of superintelligence. [9] I do not share this view, but I will not here attempt to make the argument against AI as an existential risk, as the exposition of this argument needs a time and place of its own.

As I see it, the greatest danger we face, the existential risk that ought to concern us all as human beings, is stagnation [10], or what classical historian Gilbert Murray called a failure of nerve. Here is how Murray opens his chapter on the failure of nerve in Five Stages of Greek Religion:

“Any one who turns from the great writers of classical Athens, say Sophocles or Aristotle, to those of the Christian era must be conscious of a great difference in tone. There is a change in the whole relation of the writer to the world about him. The new quality is not specifically Christian: it is just as marked in the Gnostics and Mithras-worshippers as in the Gospels and the Apocalypse, in Julian and Plotinus as in Gregory and Jerome. It is hard to describe. It is a rise of asceticism, of mysticism, in a sense, of pessimism; a loss of self-confidence, of hope in this life and of faith in normal human effort; a despair of patient inquiry, a cry for infallible revelation; an indifference to the welfare of the state, a conversion of the soul to God. It is an atmosphere in which the aim of the good man is not so much to live justly, to help the society to which he belongs and enjoy the esteem of his fellow creatures; but rather, by means of a burning faith, by contempt for the world and its standards, by ecstasy, suffering, and martyrdom, to be granted pardon for his unspeakable unworthiness, his immeasurable sins. There is an intensifying of certain spiritual emotions; an increase of sensitiveness, a failure of nerve.” [11]

Obviously, the world Murray is describing—and, indeed, the transition between two worlds that he is describing—is very different from our world and the transitions that our world suggests. Despite the distance between the world of late antiquity and our world today, there are certain parallels that can be observed. The pessimism Murray describes has its parallel in contemporary dystopianism and the casual cynicism shown to hopeful visions of the future. Instead of asceticism, we have its antithesis, indulgence—but both are focused on the welfare of the self above all.

Have we lost our self-confidence, our hope in this life and in normal human effort? Kenneth Clark in his Civilisation: A Personal View, seems to have held a view much like that implicit in Murray’s remarks quoted above. Clark wrote that civilization requires, “…confidence in the society in which one lives, belief in its philosophy, belief in its laws, and confidence in one’s own mental powers.” [12] Ask yourself if you know anyone who possesses confidence in this measure. I would be surprised if a great many responded that they did. This is simply not the character of our civilization today. Such confidence expressed today would, I think, be characterized in the most unflattering way.

That we have the technology today to do much more than we are doing at present in order to mitigate existential risk, and yet little is being done to ensure the continuity of civilization and the biosphere for the long term, is evidence of our lack of confidence in our own future. That is to say, we are already showing signs of stagnation and of disinterest in the world. In the second half of the twentieth century we saw the emergence of a counterculture that explicitly placed itself at odds with “the establishment,” embodied in such popular slogans such as “small is beautiful” and “the limits to growth.” [13] This movement celebrated a retreat from the wider world and the attempt to make oneself perfect on one’s own terms, within a tightly circumscribed horizon. This attitude must be understood as a perennial aspect of the human condition (Murray described it as such, if we understand this retrenchment from modernity as an instance of failure of nerve), and as an embodiment, in an Age of Technology, of the Romantic rebellion against the rationalism of the Enlightenment, which latter was, in turn, a reaction against the irrational horrors of the Thirty Years War and the witch craze that swept early modern Europe and America.

Image: A recent study, “Determining the Structural Stability of Lunar Lava Tube,” has suggested that lunar lava tubes may be much larger than terrestrial lava tubes, due to low gravity, as well as being geologically stable; cf. Lava Tube Moon Base.

How we get where we need to be

The maintenance or acceleration of the STEM cycle coincides with averting stagnation. As long as civilization is driven forward by unexpected and unprecedented developments in science, technology, and engineering, social transformations driven by technological transformations are likely to prevent our civilization from stagnating across the board. It would be surprising if there were not regional and limited forms of stagnation, but as long as some aspect of our civilization is breaking new ground there is a source of continued change being infused into civilization.

What can be done? How can the STEM cycle be maintained, if not accelerated? How can we avert stagnation? We can prioritize scientific projects that are likely to disproportionately contribute to the overall growth of scientific knowledge. The construction of a radio telescope on the far side of the moon (as has been advocated by SETI astronomer Claudio Maccone [14]), shielded from the EM radiation of Earth, would be both a stimulation to the space program and would result in significant scientific discoveries. While on the far side of the moon building a radio telescope, we would want to build a large optical telescope as well.

A radio telescope on the far side of the moon would necessitate a robust communication network between the lunar facilities and scientific centers on Earth. A fast internet connection between Earth and this scientific outpost on the far side of the moon would be the first stage in a solar system wide internet (Heath Rezabek has called this a solarnet; there is already internet access on the ISS via crew support LAN). With a large computer installed in a lunar lava tube to process the data (it has been suggested that we build a supercomputer on the moon), we could begin the first stages of backing up our civilization, by storing as much of the world’s knowledge as possible in this extraterrestrial repository. The first steps of backing up our biosphere, with the lunar equivalent of the Svalbard seed vault, would follow. The next step beyond this, of course, is to do the same thing on Mars, minus the purpose-built radio telescope, but with a permanent human settlement and eventually a Martian Civilization independent of terrestrial civilization.

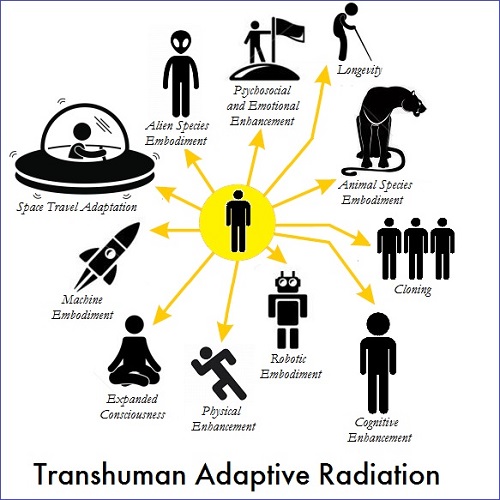

Image: Taken from an earlier Centauri Dreams post, Transhumanism and Adaptive Radiation, illustrating one aspect of the Great Voluntaristic Divergence, an adaptive radiation on a cosmological scale.]

What it might look like when we get there

Where are we going? To the stars, because that is the only undertaking sufficiently rigorous to indefinitely stimulate civilization and forestall stagnation. Our industrial-technological civilization is only about two hundred years old, and in much of the world it is far younger. We are as yet only on the cusp of the technological advancements intrinsic to this form of civilization. Once we have mastered the initial stages of technological development that come naturally to a planetary civilization, we will become a spacefaring civilization, because this is a challenge that can invigorate our civilization in the long term. [15] The stages mentioned above are mere steps in the buildout of terrestrial civilization toward an infrastructure that can sustain the exploration of the cosmos. The natural teleology of spacefaring civilization is interstellar, and then, beyond that, intergalactic travel, which will constitute the natural teleology of a multi-planetary species as it strives to multiply the planets on which it settles.

Steady advances in technology will eventually make interstellar spacefaring possible, and starships in turn will disproportionately contribute to the growth of scientific knowledge. Starships will be one more scientific instrument produced by the STEM cycle that will be employed in turn to advance scientific knowledge, and, as I have argued in The Scientific Imperative of Human Spaceflight, we will need human beings on these starships in order to derive the full benefit of scientific research. Robotic probes can expand scientific knowledge, but they cannot expand the range of a species, and even their scientific activities are limited by the absence of a conscious, embodied agent.

If the fractal structure of human history continues, we will see further exponential change at shorter time scales. A civilization at this next exponential growth stage following industrial-technological civilization is a spacefaring civilization that establishes itself as a multi-planetary species. And a spacefaring civilization is the kind of civilization that will ultimately lie at the source of what in “Transhumanism and Adaptive Radiation” I called the Great Voluntaristic Divergence. The individuals and communities that will project themselves into and onto the cosmos and thus exemplify the Great Voluntaristic Divergence, which will be marked by the self-selection of these individuals and communities, will each have their own idea of what constitutes the good for humanity, and each will act upon this idea to the exclusion of other ideas. On Earth, this process first led us into danger, which escalated into the planetary wars of the twentieth century, and then led us into stagnation, as the pursuit of mutually exclusive ideals came to be seen as an existential threat. In the context of countless worlds and almost unlimited resources, the cosmos is large enough to contain that which the Earth cannot allow: mutually exclusive central projects of planetary scale.

Perhaps this Great Voluntaristic Divergence will emerge not from Earth, but from Mars, as I recently speculated in Martian Civilization, as Martian civilization is more likely to converge upon scientific civilization than terrestrial civilization, burdened as the latter is by its long history and its many commitments to traditions arising from agricultural civilization. Martian civilization, as a de novo civilization of the industrial era, will begin as a technological civilization, and will develop from that point forward.

The idea of a cosmological expansion of terrestrial life and civilization—sometimes called the expansion hypothesis—has come under scrutiny in recent years, and appears almost as a relic of Stalinist gigantism or human hubris projected onto the universe entire. The environmental movement and the conservation ethic appear as the antithesis to technology and industrialism unconstrained even by the scope of Earth. Perhaps it will be more palatable for contemporary audiences to frame civilizations of cosmological scope in terms of divergence and diversification (i.e., biodiversity on a scale of which astrobiology can be the only adequate measure), and resilience and sustainability (sustainability for cosmologically significant periods of time), as the practical embodiment of expansion will exemplify these conservation ideals.

When civilization advances to the point of effectively eliminating technological and economic barriers to human endeavors, both individual human beings as well as human societies will be empowered to pursue projects that, by today’s standards, would be considered megalomaniacal in scope and ambition. While many will not choose such undertakings, the universe is large enough by any measure to accommodate anything conceivable by human beings, and can do so with room to spare. With the resources of the universe available to us, the point of the Great Voluntaristic Divergence is that we will not have to choose, because we will not be limited to a single planet whereupon only a single planetary civilization can play out its isolated development: one society can choose a small-is-beautiful paradigm of cooperative communities eating locally raised organic produce, while another builds megastructures, and neither need be bothered by the other.

If our civilization does not stumble again, as it has so frequently in the past, the Great Voluntaristic Divergence answers the question has to what development could follow the previous stages of exponential growth that have marked human history: outward expansion through the universe, as well as the diversification of terrestrial life as it embarks upon the greatest adaptive radiation in the history of life, which will be an adaptive radiation of both minds and bodies—corporeal and cognitive speciation on a cosmological scale. Unconstrained by the limits of a planetary biosphere or planetary civilization, life and civilization will become more diverse than we can conceptualize on the basis of life and civilization as they have been tightly constrained by the uniform selection pressures of a single planet.

Notes

[1] Completed in 1897 or 1898, it was difficult to find a buyer for the painting, through Gauguin regarded it as his masterpiece and the culmination of his life’s work. Today it hangs in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[2] Stephen of Byzantium famously said that, “Mythology is what never was, but always is.” On intuitive tractability, cf. my post The Overview Effect and Intuitive Tractability.

[3] Elsewhere I have suggested that encephalization is the great filter: Is encephalization the great filter? and Of Filters, Great and Small.

[4] In my last Centauri Dreams post, Martian Civilization, I discussed V. Gordon Childe’s conception of an “urban revolution” as the basis of civilization.

[5] Kenneth Clark, Civilisation: A Personal View, New York: Harper & Row, 1969, “The Skin of our Teeth” is the title of Chapter 1.

[6] My essay “The Moral Imperative of Human Spaceflight” attempts to provide an argument for the intrinsic value of human civilization, especially in sections 4-6. I also make this argument in the Afterword to my book Political Economy of Globalization.

[7] This argument need not be limited to human civilization, but can and ought to comprise all terrestrial-originating intrinsic value, which includes the uniqueness of the biosphere; for the sake of brevity, my exposition in the text is made in terms of civilization only.

[8] This tripartite approach to existential risk mitigation—knowledge, redundancy, and autonomy—was the subject of my joint presentation with Heath Rezabek at the 2013 Icarus Interstellar Starship Congress in Dallas, Texas, and can be found in our paper Xrisk 101: Existential Risk for Interstellar Advocates.

[9] The Founding Director of the Oxford Future of Humanity Institute, Prof. Nick Bostrom, has written a book about superintelligence, Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies (also cf. the review of Bostrom’s book by Allan Dafoe and Stuart Russell, “Yes, We Are Worried About the Existential Risk of Artificial Intelligence“), while the FHI particularly identifies “AI Safety” as a particular area of research; The Future of Life Institute features the 23 “Asilomar AI Principles” on its website, which have been signed by more than 3,000 individuals (among them Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking) and An Open Letter: Research Priorities for Robust and Beneficial Artificial Intelligence, signed by more than 8,000 individuals; there is The Centre for Human Compatible AI at UC Berkeley; celebrities of science and technology such as Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk (both mentioned immediately above), and Michael Vassar have made public statements about the potential dangers of greater-than-human intelligence AI; these examples could be multiplied at will.

[10] Nick Bostrom, mentioned above in note [9], includes permanent stagnation among his classes of existential risk; cf. “Existential Risk Prevention as Global Priority,” Nick Bostrom, Global Policy, Vol. 4, Issue 1, Feb. 2013.

[11] Gilbert Murray, Five Stages of Greek Religion, Chapter IV, “The Failure of Nerve.” The first edition of Murray’s book was titled Four Stages of Greek Religion (1912), and did not include the final chapter of the later edition (added in 1925).

[12] Kenneth Clark, Civilisation: A Personal View, New York: Harper & Row, 1969, p. 4.

[13] These particular slogans are now quite dated, but the sentiment that they expressed has arguably become even more widespread than when the slogans were introduced.

[14] Cf. Claudio Maccone, “Lunar Farside Radio Lab,” Acta Astronautica, Volume 56, March 2005, Issue 6, p. 629-639. “The Farside of the Moon is a unique place, since it is the nearest (and only) place close to Earth to be totally free from man-made RFI. As such, the Farside is just humankind’s natural spot for conducting RFI-free radio explorations of all kinds, ranging from Cosmology to Astrophysics and the radio Contact with alien civilizations in the Universe (SETI).”

[15] Cf. my earlier Centauri Dreams post The Interstellar Imperative.

“… there as yet exists no mythology that has grown out of our industrialized civilization…”

I would class the ensemble of the great works of science fiction, the characteristic literature of the 20th century, as being that mythology. One aspect of it is the wish to establish human colonies off-Earth, as so ably described in this post. It is an essentially mythological goal.

The problem of a mythology of spacefaring civilization is a large and complex topic; hopefully someday I will write a longish essay for Centauri Dreams that will go into this topic in some depth and detail. I have touched upon this earlier in “Religious Experience and the Future of Civilization” (http://geopolicraticus.tumblr.com/post/96603137352/religious-experience-and-the-future-of-civilization), “Addendum on Religious Experience and the Future of Civilization” (http://geopolicraticus.tumblr.com/post/96691585862/addendum-on-religious-experience-and-the-future-of), and “Post Axial Age Religion” (http://geopolicraticus.tumblr.com/post/144520415047/post-axial-age-religion).

There is no question that science fiction often employs archetypal characters and archetypal stories, but I don’t think that we have seen much that is truly new that can address our truly changed civilization. Perhaps, over time, science fiction will converge upon a coherent and cohesive mythology for spacefaring civilization, but we’re still at a very early stage of this development, and science fiction hasn’t yet been subject to the kind of selection over time that would make it as powerful as traditional mythologies.

Best wishes,

Nick

I am not sure that you are right. You say “perhaps, over time, science fiction will converge upon a coherent and cohesive mythology for spacefaring civilization…” That’s not quite the point: it’s the spacefaring civilization that IS the mythology. The very fact of the popularity of this website among some of the most highly intelligent people on the planet shows the power of the mythology it espouses (for as yet it is not more concrete than mythology). It is true that traditional mythologies have many more adherents, but that’s what you would expect, since the great mass of people are still rather simple and stupid and need simple and stupid things to guide them. Look at all the the science-fictional mythologies that Elon Musk espouses so enthusiastically – and he puts his money where his mouth is! None of these were even dreamed of a few centuries ago. Look at the general belief in aliens among the general population. No, I think science fiction is now guiding the hopes and dreams of almost all the effective people in civilization.

I largely or fully agree with Mr. Nielsen’s essay above , as I also commend him for his ‘Imperative’ essays.

I think I understand what Mr. Nielsen is saying or otherwise I will express my own ideas about this topic: there is, in my knowledge, no mythology, i.e. there are no (monotheistic) religions, in which spacefaring and interstellar travel explicitly feature as human purposes, let alone as divinely authorized destinies.

Religions are, usually indeed, remarkably pessimistic about humankind and human nature and rather offer us apocalyptic world views (be it in combination with some kind of external divine salvation) than views of self-realization and achievement, let alone cosmic expansion.

I myself grew up in such an pessimistic religious atmosphere (though the religious followers themselves would vehemently deny this pessimism) with strong apocalyptic expectations (read: fears) with an equally strong emphasis on personal salvation and divine intervention, and it took me many years to free myself, my thinking, my worldview and my view of humankind and its future, from it (if I even completely succeeded in this at all). I now consider all these religious world and life views factually and even morally wrong, mythology indeed.

It would be interesting to conduct a comprehensive research into the relationship between religious convictions and people’s views on space exploration.

Humankind needs a new common goal, a greater purpose, a destiny. But this destiny will have to be self-chosen, since apparently no god has given or will give this to us.

Prometheus indeed.

My college English professor who taught an amazing course on science fiction in film and literature said that is exactly what science fiction is, modern mythology. How often are advanced aliens little different from ancient versions of gods? Think the Q from Star Trek.

Then again I am thinking of the Arthur C. Clarke comment about really advanced societies with abilities being indistinguishable from magic to us. All you have to recall is how masses of people to this day willingly interpret stains on a wall or the appearance of a bright comet as signs and omens from some supernatural deity.

We still have a long way to go, though we have accomplished a lot considering all the setbacks and our limited perspectives being stuck on one planet so far.

Although you indicate ‘stagnation’ as the major civilization problem, I have seen nothing to support this idea. Nuclear war, however, could take humanity back to the stone age – or eliminate the species entirely. The fact that we are not practicing drills hiding under our desks and tables, perhaps distracts us from the real danger. The correct emphasis is that of Elon Musk and other visionaries to make us 2 planet species as soon as possible. There may be no second chance.

I don’t think that nuclear war could have such a drastic effect.

I hope you’re right (and you may be), but *that* is one “experiment” that I fervently hope is never performed (I’m sure that you share that hope). But given the characters who have nuclear weapons now–and those who are approaching the capability of producing their own–we may yet have such a “conflictagration.” Such a horrifying event might, however, have a silver lining:

India and Pakistan (to give one example), who had three wars and openly threatened further mutual conflict before India exploded a fission bomb in 1974, are now less openly belligerent toward each other because–with both now being nuclear weapons-possessing states–they know that a political mis-calculation could set their countries back to iron-age conditions, or even worse. This suggests the possibility that:

A nuclear conflict between such states with smaller nuclear arsenals (or between a nuclear-armed terrorist group and any state) might shock the world so much that mass movements could change existing human assumptions–and the societal and political structures that stem from these assumptions–completely out of recognition compared with what had gone before. To put it colloquially, the message of John Lennon’s song “Imagine” just might, in some form, become a reality. If so, colonization of other planets and interstellar travel might no longer be seen as dreams or luxuries, but as prudent “existential insurance” for terrestrial life, including humanity.

A limited war between, for example, Indian and Pakistan, would cause enormous destruction, but it wouldn’t extinguish life in either country, and there would later be massive aid from the civilized world for rebuilding. There would be no question of either country being reduced to the medieval level.

That assumes such a war would stay limited (it might, and hopefully it would), and that no other world nuclear powers either got involved, or were brought into such a conflict by being struck themselves (as Saddam Hussein struck Israel during the first Gulf War, hoping to goad them into joining battle). A terrorist group with nuclear weapons might do the same thing, as might a nation like Iran. The radioactive fallout and Sun-dimming dust from even a limited Indo-Pakistan nuclear war could cause worldwide sickness and food shortages, with economic consequences even for the developed world.

I disagree. I think nuclear war would indeed have drastic, possible irrevocable effects on the trajectory of the human species. A nuclear war between major powers could easily cause modern civilization to collapse into barbarism and anarchy. After a large nuclear exchange, mass starvation due to the collapse of the industrial food-system and the collapse of modern medicine would likely cause more fatalities than the explosions themselves– not to mention possible strikes on nuclear power plants resulting in even more radiation from meltdowns. There is no guarantee that after such a cataclysm humanity would ever recover to the point of becoming a high tech, space-faring civilization. Furthermore, a devastating nuclear war occurring in the context of a biosphere already in decline for other reasons might result in perilous, synergistic, negative ripple effects thereby increasing the probability of eventual human extinction.

I think that is an exaggeration. Yes, after a general nuclear exchange there would be great confusion and anarchy, and more than half of the population of the affected nations would probably die. But nobody is going to bother bombing all the nations of South America or Africa, because they are not strategically involved with the quarreling parties. They would be relatively unaffected. (H. Beam Piper saw all this in the 1950s.) And all over the world, even in the worst hit countries, the information necessary to rebuild modern civilization would be preserved in libraries and personal archives. Humanity would still be a high-tech civilization. And I don’t take much stock in the suggestion of a “collapse of the biosphere”. I am sure it can take one hell of a lot of radiation.

Whenever I read about a “winnable” nuclear war, I always think of this line from Dr. Strangelove:

https://youtu.be/GrQbFb4cJt8

The study of nuclear winter made people start to realize that even places on Earth not directly touched by a nuclear strike could still suffer the consequences:

http://www.bibliotecapleyades.net/ciencia/ciencia_uranium16.htm

My assumption is that in keeping with the age old trends here on Earth, the decendants of any Martian settlers will be prone to develop an aggressively protectivist attitude toward their home world which could under inauspicious circumstances eventually morph into a hatred of the Earth. A new threat to life on here ironically born out of the ideal to reduce that threat. A new planet does not create a new mindset.

That can’t happen for quite a long time, because Earth is where they will be getting their spare parts and their high-resolution chips from, for the foreseeable future. To recreate a complete high-tech civilization on another planet will require hundreds of thousands of trained specialists and specialist equipment, and it will take centuries to build those up. See Vernor Vinge!

Centuries? Not necessarily. There would be an initial significant dependence on Earth; however, with advances in 3-D printing, robotics, AI, new methods of energy generation, nanotechnology, etc. the dependence might not last for as long as some think. In line with the tightly-coupled STEM cycle which Nick refers to in his excellent article, we cannot assume that innovations will occur so slowly during an era of space colonization; in fact, the development of whole new, unforeseen technologies and creative enterprises would likely ensue as part of a dedicated expansion into the solar system.

I would be surprised if such an attitude *didn’t* arise–to some extent–among the Martians, given the harsher conditions and the much greater reliance on technology for sustaining all aspects of life (food and water as well as air) that they will have. While I’m sure that people living on other worlds and/or in space colonies won’t become perfect (even one of the Skylab crews colluded to commit a “crime”–they deliberately tried to conceal a crew member’s temporary illness from Mission Control, and that was a “space community” of just three men), the kinds of extreme disagreement and conflict that human beings can have on Earth (and still survive as a civilization) are “luxuries” that off-world settlers simply won’t be able to afford. Also:

That enforced need to get along together will, I think, lead to a strong camaraderie and sense of community, and a disdain toward most Earth-dweller’s ways, particularly among native-born colonists who have never been to Earth (“WE can live in peace together–why can’t they?”). Arthur C. Clarke foresaw such an attitude developing on Mars, and science writer Neil P. Ruzic envisioned the same attitude arising among lunarians in his 1970 non-fiction book, “Where the Winds Sleep: Man’s Future on the Moon, A Projected History.”

We haven’t been back to the moon in more than forty years and you see nothing to support stagnation?

The moon is like Mars. There has to be some cost effective reason to send men back to the moon when robots can explore the moon more effectively.

Given the lack of habitable locations in the solar system, O’Neill colonies might be our best bet for long term manned space exploration. If successful, perhaps these colonies could evolve into multi-generation space arks capable of interstellar travel.

I am neither an engineer nor an economist, but it would make an interesting study to estimate what it would actually take to expand humankind into the galaxy.

First calculate the cost of an O’Neill colony. (Allow for the inevitable setbacks and cost overruns.) Then calculate the cost of a follow on program to build a space ark capable of traveling maybe 5% the speed of light.

Then calculate the GDP of Earth’s industrialized nations and assume they might band together to fund the project. Estimate the size and growth rate of these nations’ GDPs. Factor in the cost of international priorities such as preventing or adapting to global warming, Factor in individual nations’

priorities such as funding defense, education, national retirement and health systems, etc. Then calculate at what point in the future, (if ever) world GDP might be large enough to fund a space ark.

I realize this study would be mostly guesswork, but it would at least allow for an intelligent guess. And it’s no more of a guess than the Drake equation, which everyone loves to speculate about.

Islam takes us back to the stone age. Look at what happened to the southern half of the Roman Empire the last thousand years or so with no end in sight of the misery, slavery, murders, terror, wars, poverty, backwardness and oppression. And now islam is taking over all of Western Europe too. No science or industry is possible in muslim societies, as all of history shows. In a few years Europe will no longer have any space industry.

A nuclear war could be brushed off and repaired. But a stone age mindset of hate and violence and total intolerance against and rejection of all human culture and science, that is incurable. Besides, who will start a nuclear war if not the suicidal muslim maniacs? The real danger to the survival of life from Earth comes from islam, the inhuman anti-development ideology which now so very fast is putting islamic provinces like the UK and France under the bloody stone age tyranny of its islamic state califat and its inbred dement warlords.

Islam was founded in the 7th century CE. Yet Arabic scholars were advancing mathematics in the 11th century and preserving not a few documents after the fall of Rome and before the Renaissance. Like Christianity, the problem is the interpretation and the political institutions. Christianity was just as doctrinaire at one time, and the fundamentalist interpretation of Islam that has been adopted by small groups is not so dissimilar to fundamentalist Christianity. As Christianity managed to throw off its doctrinaire approach, there is no reason to doubt that Islam can follow suit as their populations modernize and the extremists are isolated.

As far as I am concerned, what is important is to maintain the Western Enlightenment. That doesn’t mean it has to be maintained by Europeans or their offshoots, but by any culture that supports that way of thinking to progress.

Living in the US, a Christian dominated (still) society, I am concerned that a sizable fraction of the population reject science, a trend that has infected one political party. This looks very much like a move towards a time when Catholic religious doctrine was dominant in Europe (and still is in some countries).

For me, it is conformist ideology that is the problem, as it fundamentally conflicts with scientific thinking.

Fundamentalist Islam takes us back to the stone age. So does fundamentalist Christianity, fundamentalist Judaism, fundamentalist Hinduism, etc. One of civilization’s worst and most powerful enemies is fundamentalism which cares not at all for truth, only for adherence to its particular myths and thinks it has the right to impose those myths on everyone. Fundamentalist Islam is a danger to a lot of people but fundamentalist Christianity is the bigger danger to America because a lot of our political leaders are in thrall to it.

Perhaps true; perhaps wildly exaggerated; but still OFF TOPIC.

Nitpick: Human cranial size has reduced since the advent of civilization, possibly due to “domestication”. OTOH, our tools have dramatically expanded our thought processes, shifting them from wetware to artifacts.

The assumption in this piece is that humans (1.0+) will/could create the great expansion to the stars. Perhaps this is no different than Devonian fish dreaming of expanding onto the land and into the air. Evolution could be considered their version of our transhumanism. However, our intelligent machines, already taking the furthest steps, are possibly more likely to make the transition as they are “pre-adapted” to operating in far more diverse conditions and have no need to bring along biospheres. Human embodiment in machines/robots might be one way to match this, but it may also be too limiting. What it means to be “human” may not be competitive with de novo machine intelligence and may be outcompeted as were the Neanderthals.

We have all grown up with stories of humans triumphantly “conquering” the stars [ ” It is this, or that – all the Universe or nothingness! Which shall it be, Passworthy?” – Cabal ] and so it seems natural to place ourselves in that role, if only to sell stories. The future may see us displaced from the center of things, just as we humans have displaced those ancient fish.

Thanks for your nitpicking criticism. Human beings overall were reduced in stature in the transition from hunter-gatherer nomadism to settled agriculturalism, with the latter’s need for grinding work every day and reliance on a monoculture grain diet, and human brains were also reduced in size by this development, though since the advent of better nutrition and scientific medicine human beings are close to being back where we were 10,000 years ago.

As to your other point, human beings may well be displaced by something better, or by simply failing catastrophically and going extinct we may be displaced at the top of the food chain by something no better than us. However, human beings going to the stars isn’t like Devonian fish dreaming of expansion on land, and this is because we have passed a cognitive threshold that allows us to use our intellect to do what other species have not been able to do. We can do this by encasing ourselves in a miniature ecosystem that supports our embodied form, or we can do it by changing ourselves. Devonian fish couldn’t build landsuits for themselves and they couldn’t change themselves. Instead, this was supplied by time and other species.

That we might possibly be successful in expanding into the universe as embodied human beings does not mean that it will happen, only that you can’t write us off yet. And I, for one, will fight the good fight against any machines who would seek to supplant us.

Best wishes,

Nick

Nick, the brain size issue isn’t so easy to dismiss. See here.

Fair critique of the fish analogy. However, my point is that we cannot adapt to space as flexibly as a machine can be adapted to it. We are bound by biology that is unsuited to this environment without a suitable biosphere wrapped around it. Humans colonizing space is as ill-suited as those fish colonizing the land using aquaria. In their case, their biology was unsuited. In our case, biology itself is unsuited.

While you suggest that humans can be embodied in machine bodies, I have to wonder it they will be human at all in any sense we understand the term. Such an embodiment will require mind uploading (keeping the wetware is insufficient). An AI would be easier to construct de novo and be better suited as it will not need all the baggage associated with the original host’s biology. In a competitive situation, it seems to me that machines will far outpace us, able to colonize niches that we cannot go if we are to retain our biology, even at a tardigrade’s level of robustness. A mind uploaded human would be the most likely competitor, but how human would such an entity be?

Humans might coexist with machines in space, but I think we will be as restricted as the last Neanderthals. Our human minds in machine bodies left behind in adaptability as machine minds rapidly evolve in many directions. OTOH, it may be that evolution has given us extremely good minds that cannot be matched by AIs, so that machines can only spread widely, but not compete with us.

Please don’t fight against aliens’ quantum AI, the delusions of winning only exist in brain’s simulations just like in the state of quasi-coma.

I am not a troll, and I mean this sincerely and without rancor. I feel nothing but love and respect for Nick, no doubt a good person. But Nick could not be more mistaken.

Modern Promethean (Luciferian) civilization will “stumble” again, something that is desperately needed for the good of our physical home planet and our own souls. What Nick views a a stumble is more similar to a long delusional alcoholic finding sanity and sobriety. The Promethean ethos is the ethos of a cancer cell. The problem with cancer cells is that they have lost the plot, they no longer sense the body of which they are a part as anything other than a food source. Humanity’s current delusion that it is the crown of creation and alone in the universe is not progress, it is a sickness.

“an indifference to the welfare of the state, a conversion of the soul to God.” is exactly what is needed. Unfortunately, given human nature, this can only happen when we hit rock bottom.

FYI, NATO just held a big exercise near Regensburg, led by a brigade from Latvia. Russian speakers were hired at a rate of 120 euro a day to play the enemy. I would not be surprised if footage of this event is later shown on CNN as an invasion of Latvia by Russians and a casus belli for WWIII. (In 2014 the global media showed archival pictures of Russian troops in Georgia 2008 as (fake news) proof of a current invasion of Ukraine). Rock bottom might be a lot closer than we think.

Promethean is Luciferian? Whatever. I absolutely agree that ignorance paired with hubris is a toxic combination. Add to that our intensely tribalist nature that covets the familiar and shuns the foreign. But with al due respect for your spiritual convictions you might want to ask yourself if your proposed theological approach itself is not actually part of the problem.

The “conversion of the soul to God” that Joy thinks necessary and that Nick alludes to coincided with the fall of the Roman Empire. As western civilization collapsed, people gave up on worldly progress and hoped instead for a better life in heaven. The same attitude motivates suicide bombers today.

A more basic problem with this idea is that there is no God and never has been. We’re all we got. Ironically, given the speed of light and the amount of energy required, Nick’s vision of galactic expansion is almost as far fetched as a religious vision.

As I’ve pointed out before, Antarctica was discovered about 200 years ago. And even though it has breathable air, normal gravity, plenty of water, and is warmer than Mars, no one has ever chosen to live there on a permanent basis. So as an intermediate goal of space exploration, what nation is going to spend the money to settle Mars, much less even more inhospitable locals in the solar system?

Lastly, I think it’s important to keep in mind the sigmoid curve, or S curve for short. Yes human technology has expanded exponentially over the last several thousand years. But trees don’t grow to the sky. At some point in the future technological progress will level off. Maybe it will be in a 100 years, maybe 500. But given that our growth started around the stone age, it’s reasonable to think we are closer to the top of the curve, than the middle. (For example, see “The Rise and Fall of American Growth” by Robert Gordon.)

Afterlives in better places are a recurring feature of human religions. What changes is how you get there.

We have no evidence for any overall decline in technological growth. Yes, some of the more manifest technology changes happened in the 20th century, but important new technologies are constantly appearing. I tend to think that increasing technologies create even more new technologies due to increasing combinations that are possible. [BTW, Robert Gordon is concerned with productivity, not technology. Productivity is easy to measure when outputs are commodities, but quality is much harder to factor in.]

“there is no god and never has been”

Indeed:

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

The Diamond Sutra – A New Translation by Alex Johnson, Chapter 14:

Such a person will be able to awaken pure faith because they have ceased to cherish any arbitrary notions of their own selfhood, other selves, living beings, or a universal self. Why? Because if they continue to hold onto arbitrary conceptions as to their own selfhood, they will be holding onto something that is non-existent. It is the same with all arbitrary conceptions of other selves, living beings, or a universal self. These are all expressions of non-existent things.“

Also see Lawrence Krauss “A Universe from Nothing” https://www.amazon.com/Universe-Nothing-There-Something-Rather/dp/1451624468/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1491141772&sr=1-1&keywords=a+universe+from+nothing

That fatuous philosophy is shown to be the nonsense that it is every time a mother–whether human or (another) animal–beholds her newborn, lovingly looks after it, and protects it from harm (and mourns its death if it dies), because she knows–without needing to be told–that her child *is* another living being, of a kind similar to herself, yet a unique individual.

That attitude (which discourages the curiosity about the natural world from which science and all exploration, including space exploration, spring–why bother exploring anything, if they’re just “illusions?”), which leads to that sterile view of life and existence, is suspiciously similar to that of the drug addict who is seeking to escape all forms of pain:

Convincing oneself that all is illusion and that oneself, other selves, and living beings are non-existent is but another way to avoid pain; if they’re only illusions, then their sufferings and deaths (as well as one’s own) are likewise only illusions, nothing to get upset over. But I have yet to meet a Buddhist or Hindu who didn’t mourn the loss of a child, parent, sibling, friend, or pet, saying that they were just illusory conceptions. I guess they aren’t “enlightened” enough; may they never be.

“… Nick’s vision of galactic expansion is almost as far fetched as a religious vision.”

I would agree with that; in fact, I would go further. It IS a religious vision – a mythical vision. Which means it is uniquely able to power men’s actions.

But I violently disagree with the application of the sigma-curve. I do not think that technological progress will level off for the foreseeable future (which would presumably happen when we have discovered more or less all that there is to discover).

It depends how you define “foreseeable future.” I agree that rapid technological growth will probably continue for a few hundred more years. But eventually technological progress will level off.

Also it’s possible that factors like climate change, overpopulation, mass migration, social unrest, etc. could stop the rate of growth in less than 100 years.

I’m with you here; only such mythical visions have the power to *draw* people to try to reach them, to make them manifest (as opposed to negative visions, which people–if convinced they could come to pass–will act upon in order to avoid having them come to pass). While positive visions are usually more effective (because people act out of their passions and aspirations to make them happen), even negative visions can–if framed properly, by pointing to an even better future beyond the “rough patch”–draw people to try to reach them. For example:

Wold War II was probably the darkest period in living memory, and the allied governments were quick to point out–particularly after the United States entered the war–the consequences of doing nothing. But they also pointed to the peace, freedom, and prosperity that would return, and likely in larger measure, after the Axis Powers were defeated. In an interstellar travel context, such a “turning lemons into lemonade” situation might go like this (if a reachable, truly Earth-like exoplanet with no indigenous intelligent life was found; those are admittedly big–but not impossible–“if’s”):

If our Sun showed signs of going nova, or of becoming too variable for life on Earth to survive (I even once read an article whose scientist author warned that the solar neutrino count suggested that nuclear fusion in the Sun’s core might slow down greatly; hopefully that was just an instrumentation error…), that negative vision would impel humanity to–reluctantly–consider moving to such an exoplanet (or at least sending enough people there to ensure that humanity would survive). But it would also, potentially (especially if there was enough forewarning) be a “carrot” as much as a “stick,” offering a chance for human beings–perhaps even all of them, who wished to go–to literally make a fresh start, on a new world.

– Bladerunner

Where Joy might see human expansion as a “cancer” (not a unique perspective by any means) others see this as increasing the power of human thought and possibilities.

But let’s look at the cancer analogy a little more closely. It assumes that the body is the proper functioning unit and that te cancer cell, with it’s disrupted genome, is the “disease” because it destroys the body.

A cancer cell, if it could think, might regard other cells as highly restricted. living highly structured lives, whilst it can throw off the bonds and replicate as it might.

The idea that the natural world is some sort of paradise that humans have disrupted is a romantic view. Unlike cancer cells, humans can think, can coordinate, and can create conditions that could be better than nature ever could on its own. Life is constrained to earth, but humans could create new biospheres on dead worlds around other stars, increasing the potential for life to explore more of its space of possibilities.

Humans certainly have not done a great job of cleaning up after themselves. Life never has, with the great oxygenation event as a good example of plants polluting the early atmosphere and ruining it for anaerobes. It is not an immutable feature of human society, we can ensure that we don’t pollute, that expansion improves rather than destroys ecosystems. Cities are far cleaner and more pleasant to live in than they once were. Those pretty ruins of ancient cities may look nice, but modern humans would have trouble living in the filth and stench of those cities. Rome may have housed as many as 1 million inhabitants at its peak, modern cities are far larger and more livable. Why should that not continue to improve?

Unlike animals, humans preserve parts of the natural world by law. Unthinking cancers don’t keep parts of the body off limits to maintain it.

Human stupidity may cause civilization to fall, but human thinking could also create civilizations that far surpass ours in terms of possibilities for humans (and nature) to develop.

“Those pretty ruins of ancient cities may look nice.” Yes indeed. That’s because only the stone structures survive. The wooden or canvas dwellings of the slaves rotted away centuries ago. Gone too are the open sewers, slums, slaughter pens, brothels, etc that existed in these once great cities.

I understand and agree with you, Joy.

Occasional injections of humility (not humiliation) are good for individuals and for societies, for they make it possible to slow down and experience–even if only for brief periods–contentment. For individuals at least, it isn’t even necessary to experience humility and contentment as results of some setback or “hard knock”; just intentionally stepping back from our busyness of life is sufficient to get there. Also:

I disagree with Mr. Nielsen’s point (that he expressed himself, and also via a quotation from Gilbert Murray) that asceticism and mysticism are symptoms of a failure of nerve. Not only have some of the greatest scientists also been mystics (Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton are two famous examples; more recent ones include Descartes, Bohm, Tesla, and Einstein), but engaging in mysticism–as I know personally from shamanic drumming experiences–requires both daring (the very opposite of “failed nerve”) and humility.

Humility is required because one must admit that the human mind *isn’t* necessarily the highest intellect or agent of empathy around (before one can even try it, one must first “get over one’s own pride”). Daring is required in equal measure, because one is connecting with other entities and realms, and it is immediately clear who the junior partner in all such contacts is (although it is fortunately not a common occurrence, some who have not shown due respect have been chastised, very occasionally to the point of being driven mad). In addition:

Far from engaging in mysticism (and asceticism is just one method, among several, of reaching the appropriate state to do so) being a symptom of pessimism about this world, those who engage in it–including myself–do so because the world that we see is just a small portion of all that is. (One might just as well say that those who explore the oceans are pessimistic about the land, or that those who engage in space exploration are pessimistic about the Earth, when nothing could be farther from the truth; they are simply fascinated by new and different places to explore.) As well:

I too see the social order that we now have as being cancerous, because it can’t survive unless it can keep growing, and rapidly. (I fight it by *not* participating in it–by not accumulating more and more “stuff” that I don’t need, to impress people I don’t even know.) It also, at the present time, appears fragile and vulnerable (it certainly is economically; a few big blows due to terrorism or a new war might bring it down). But:

Unlike the hippies, I don’t cheerfully shout, “Bring it all down, man!”, because what replaces the current order could just as easily be worse–and perhaps far worse–rather than better. (While most advocates of off-Earth colonization think in terms of *physical* survival, having “spare tire” human societies elsewhere could also help ensure that at least some humans can continue to live in freedom and prosperity.) And in that connection:

While the material and energy resources available in space are indeed vast, the difficulties of building and maintaining artificial habitats out there would, I think, make the “endless, rapid growth” model that currently hold sway on Earth less tenable off the Earth; slow, gradual growth seems more likely. (At the very least, denizens of off-Earth communities would learn that “The best things in life are free,” such as the magnificent views!) Another, purely human, factor should also operate in favor of this outcome:

How many people, when one really gets down to brass tacks, would actually move out there? Talking about it and its advantages is one thing, but even the physicist Freeman Dyson–who is very interested in such matters–admitted that to him, life in an O’Neill space colony would be too sterile for his liking. Unless warp drive or something much like it is developed, the rosters of volunteers for interstellar journeys would likely be even slimmer (particularly if truly Earth-like planets, where one could live as on Earth, are either non-existent or unreachable), because they would be leaving the Earth behind for decades (and more likely, forever). While endeavoring to help end hunger, want, and disease for others, we must learn–or rather, remember–how to be happy where we are.

This is such a wonderfully detailed and well thought out comment that it deserves a response of similar scope, but I’m not prepared for this at the moment. I hope to return to this.

Nick

Thank you, Nick. I advocate off-world settlement, for those who wish to do it, and I’m sure some people would go–even on the most spartan, multi-generation “slow-boat” interstellar voyage. (While I wouldn’t care to live on the Moon, Mars, an O’Neill space colony, or even an Earth-like exoplanet for the rest of my life, I would love to visit such settlements if two-way travel was comparable in speed, safety, and cost to terrestrial travel [that would of course require Alcubierre’s warp drive, Forward’s “twistor drive,” Tipler’s “time reversal,” or stable wormholes, in the case of exoplanet visits].)

My only disagreements concern why it should be done, and how those who go should conduct themselves. Ripping up other worlds with abandon to obtain resources, “just because there are no natives to complain about the ugly scars in the ground” (I would like to think that many of the settlers themselves would object to resource extraction done with no consideration of other worlds’ natural beauty and their environments, however hostile they might be to life), would not be a hallmark of a maturing civilization.

Such considerations were advocated in the World Space Foundation’s 1990 book, “Project Solar Sail,” and Arthur C. Clarke predicted–in his 1968 book, “The Promise of Space”–that two hundred years from then, committees of earnest (lunar) citizens would be fighting tooth and nail to save the last unspoiled vestiges of the lunar wilderness.

‘led by a brigade from Latvia’

1000 to 4000 men, Hardly a huge army !

A dictators downfall is that his reach is always greater than that of which he can hold.

Dear Joy,

Thank you for you kind words about me personally, and I understand that our differences are not a matter of rancor, but of a fundamental difference of viewpoint.

You have cited the story of Prometheus, and this is instructive. Prometheus stole fire from the gods for mankind, and was punished by Zeus for this transgression. When Prometheus was bound to a rock and a great bird came to peck away at his liver each day, Hermes came to Prometheus with a kind of a peace offering: apologize to Zeus and all will be well again. For me, it is one of the most thrilling moments in western literature that Prometheus spurns the offer and accepts his punishment.

Somewhere in one of his lectures, Joseph Campbell compares the story of Prometheus to Job, who, when shown the power of God in a whirlwind, says, “I abhor myself, and repent in dust and ashes.” Campbell rightly notes that “No Greek would have ever said that.” Prometheus did not abhor himself. Here we are presented with a fundamental temperamental difference that has, over the course of human history, been implicated in fundamentally different central projects of civilization. And this is why Tertullian famously said, “What, after all, has Athens to do with Jerusalem?”

I am an unabashed admirer of Prometheus and the Promethean spirit, and I look forward with great anticipation to humanity further harnessing the gift of fire, even if we continued to be punished by the gods for our hubris, and even if, those whom the gods destroy, they first drive mad.

Very Respectfully Yours,

Nick

Spoken in the true Faustian spirit!

Those are, to me (the attitudes of Job and Prometheus) two extremes of human attitude, neither of which is either useful or flattering. Human beings usually think of good and bad, or positive and negative, as being at opposite ends of a scale, but what is desirable usually lies in the middle, with opposite but equally undesirable things at either end.

The Gray Path (also called the middle way) seems more desirable than either a cringing “We’re not worthy!” attitude on the one hand, or a prideful “our race can do whatever it wants–WE are the pinnacle of nature, and can conquer it!” attitude on the other. Between the two lies the “sane center,” whose attitude (toward exploits both on and off the Earth) can be expressed this way:

“We will use the resources of the Earth and other worlds in order to survive and thrive, but not at the expense of the continued existence of other creatures thereon–whether they be intelligent or not–because we cannot exist, or even be happy, totally apart from nature [this is becoming painfully obvious here on Earth]. We are a part of nature, so we need not be intimidated by it–we have as much right to be here as the cougar and the buffalo–but we must not commit the folly of thinking that we can set ourselves above it or beyond it, unaccountable and untouchable by the consequences of our attempts to subdue nature. At most, we may bargain with nature–using its laws to our advantage–but never to excess, as the harm that accrues therefrom will always affect us.”

We can see that Prometheus is truly a myth. A clever historical Greek would have apologized to Zeus to end the torture, because the apology did not require that mankind give back the gift of fire.

You say that Promethean (Luciferian) civilization will “stumble” again. This is precisely the Spenglerian viewpoint, although he calls our current civilization the “Faustian” civilization. His thesis is that all Cultures rise, evolve (harden) into Civilizations, and then decay.

Personally, I disagree. I think that the phenomenon of the Enlightenment and the consequent great development of science and technological knowledge has presented a new situation, and collapse and decay (which you seem to welcome) is by no means inevitable.

As for all the other stuff in your post, I completely reject it, but since it is all off-topic, I won’t discuss it.

As for all the other stuff in your post, I completely reject it, but since it is all off-topic, I won’t discuss it.

The subject of Mr Nielsen’s article makes poster Joy’s comments very much on topic. Although CD generally tends to discourage political and metaphysical considerations, he has opened the door for these kinds of discussions in comments here. To do otherwise would be grossly unfair. We certainly may discuss it and I hope Mr Glister will concur.

The level of discourse in comments on this article is very high. So many of the things I would say in reply have already been said. I appreciate Mr Nielsen’s thoughts and welcome his article exploring this dimension of the human or trans-human journey. I also think there are many assumptions and some conflations in his writing but am glad his article has provided the community an opportunity to explore these ideas.

Prometheus, Lucifer, Faust… these are emblematic names for the struggle of the human spirit’s struggle on its own abilities. 2001 – a Space Odyssey” movie did not choose “Also Sirach Zarathustra” for no reason. It is a clear philosophical reference to the superman who is beyond the limits good and evil.

That world can indeed be represented as a civilisation that requires “…confidence in the society in which one lives, belief in its philosophy, belief in its laws, and confidence in one’s own mental powers.”

Some will question if such a civilisation truly has the “big picture” where there are more things in heaven and Earth than are dreamt of in such a philosophy. Certainly, the counter-culture explored an expanding universe of worlds beyond ken without physically leaving the planet.

Carl Sagan, the hero of interstellar dreamers and wormhole wonderers everywhere, smoked pot. What about the credo “War is unhealthy for children and other living things.” We shouldn’t mischaracterise a counter-culture which, to its credit, was never monolithic.

The counter-culture won the culture war. The evidence is all around us; for example, legalisation of cannabis and the resilience of the Affordable Care act to name a few.

At the same time, dialectic reaction propels us in the opposite direction.

Will there be a synthesis, and for how long?

STEM is a trendy acronym in education today, however in my experience it stands for Science Teaching Enfeebling Mendacity. I was a science and math teacher in a former life, and a physics student in a life before that. Education is not advancing, it has been dumbed down for more than a generation. Science education is not empirical, it is rote learning. It is dogmatic Aristotelianism. It destroys the intelligence of our youth and inhibits true innovation. Look at the considerable resistance in these threads to empirical evidence encountered in breakthrough propulsion that suggesting that there are holes in our basic understanding of physics. I think this is the real stagnation and failure of nerve if we are to go where no man has gone before.