How do we create our image of other worlds? The obvious answer — through instrumentation on space probes — is inadequate, because the raw data sent back by our spacecraft has to be assembled into the final images we see. Consider Hubble, which uses filters recording different wavelengths of light, and then combines them to create the image. Nor do we need confine ourselves to visible light, since we also get images in the infrared, and views filtered in whatever way will maximize science, like some of Cassini’s radar images of Titan. Instead of just seeing an image, we assemble it.

What you would see if you were actually there, in other words, isn’t necessarily what you get. I notice that Elizabeth Kessler, a doctoral student in the University of Chicago’s Committee on the History of Culture, has presented her work on Hubble and artistry at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington. The title of her talk, “Hubble’s Vision: Imaging, Aesthetics and Public Reception,” points to how much the Hubble data is in reality a translation by image specialists whose choices affect the final composition.

Here’s Kessler in a press release from the University of Chicago, made available via EurekAlert:

“There’s a lot of translation that occurs between the data the Hubble collects and the final images that are shared with the public,” Kessler explains. Translating raw data into the ‘pretty pictures’ that have become a staple of newspaper front pages requires careful image processing. Astronomers and image specialists strive for realistic representations of the cosmos, yet they make subjective choices regarding contrast, composition and color. The Hubble images are complex representations of the cosmos that balance both art and science. In that sense, as well as in their appearance and emotional impact, Kessler says they resemble 19th century Romantic landscape paintings, especially those of the American West.

“The aesthetic choices made result in a sense of majesty and wonder about nature and how spectacular it can be, just as the paintings of the American West did,” Kessler said. “The Hubble images are part of the Romantic landscape tradition. They fit that popular, familiar model of what the natural world should look like.”

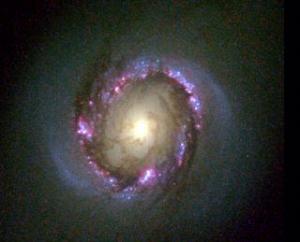

Image: Astronomical ‘art’ that feeds the imagination. This Hubble telescope snapshot reveals clusters of infant stars that formed in a ring around the core of the barred-spiral galaxy NGC 4314. This stellar nursery, whose inhabitants were created within the past 5 million years, is the only place in the entire galaxy where new stars are being born. Credits: G. Fritz Benedict, Andrew Howell, Inger Jorgensen, David Chapell (University of Texas), Jeffery Kenney (Yale University), and Beverly J. Smith (CASA, University of Colorado), and NASA.

Image: Astronomical ‘art’ that feeds the imagination. This Hubble telescope snapshot reveals clusters of infant stars that formed in a ring around the core of the barred-spiral galaxy NGC 4314. This stellar nursery, whose inhabitants were created within the past 5 million years, is the only place in the entire galaxy where new stars are being born. Credits: G. Fritz Benedict, Andrew Howell, Inger Jorgensen, David Chapell (University of Texas), Jeffery Kenney (Yale University), and Beverly J. Smith (CASA, University of Colorado), and NASA.

The image above is just one from Hubble’s endless gallery of celestial art. But consider, too, how often language has carried the sense of discovery that brings people to the study of astronomy and astrophysics. I recently re-read a creaky science fiction story from the 1930’s, Neil Jones’s “Planet of the Double Sun,” which ran in the February, 1932 issue of Amazing Stories. Jones would never be accused of being a great writer, but his depiction of the interstellar adventures of Professor Jameson, developed in a series of tales in the 1930’s, influenced Isaac Asimov’s robot stories (“What I responded to was the tantalizing glimpse of possible immortality and the vision of the world’s sad death,” Asimov would later say) and painted images of celestial wonders that shaped our view of interstellar travel.

Consider this scene from “Planet of the Double Sun,” in which Jameson and his robotic colleagues walk out onto a planet that, however scientifically inaccurate, surely helped give birth to that ‘sense of wonder’ that brought so many young people to the study of science:

From where he stood with his companions upon a comparatively lofty eminence, Professor Jameson gazed out over a silent sea whose waters spread away to meet the far distant horizon. The crystal clear atmosphere of the planet appeared to be of a rarefied nature, or else it supported little dust, for several stars of the first and second magnitudes were clearly visible within the sapphire vault of the sky’s illimitable depths. The blue sun, being of a slightly fainter intensity than its lesser companion, now occupied the zenith, being not quite directly overhead, while the orange sun rested upon the watery horizon, preparing to sink out of sight…

The orange sun’s burnished disc drew gradually toward the vague line which marked the blending of violet water with sapphire sky. The burning orb slowly sank among a few wisps of multicolored clouds drifting on the far distant horizon of water like dim ghost ships. Sinking, sinking, as if reluctantly bidding its blue contemporary farewell, it passed slowly into the translucent depths of the peaceful sea which lapped a distant shore.

We need the imagining of such places, even as we refine the science to understand why some celestial scenes are more likely than others. The blue star in Jones’ scenario presents a number of problems in orbital dynamics, but many of our recent breakthroughs have found places even stranger — who would have dreamed of the ‘hot Jupiters’ that hug their stars in orbits that take mere days to complete? And who knows what other scenes we’ll find that make the description of Jones seem tame by comparison? On that score, be aware that the superb space artist Lynette Cook will soon release Infinite Worlds: An Illustrated Voyage to Planets Beyond Our Sun, which brings many of these worlds, already found by science, to realistic life.