The death of Hans Bethe has been covered by the media worldwide, and William J. Broad’s obituary in the New York Times seems among the most thorough and accurate of the accounts of his life. But to me, Bethe will always be seen through Richard Feynman’s eyes, and I think Broad misses the point of the one Feynman anecdote he tells.

Feynman first worked with Bethe at Los Alamos during the days of the Manhattan Project, and he recalls the physicist’s openness to debate, and his focus on the issue at hand rather than personality. Here, Feynman has just arrived in Los Alamos, and work had just begun, as told in the wonderful Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! (New York: W.W. Norton, 1984):

Feynman first worked with Bethe at Los Alamos during the days of the Manhattan Project, and he recalls the physicist’s openness to debate, and his focus on the issue at hand rather than personality. Here, Feynman has just arrived in Los Alamos, and work had just begun, as told in the wonderful Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman! (New York: W.W. Norton, 1984):

“Every day I would study and read, study and read. It was a very hectic time. But I had some luck. All the big shots except for Hans Bethe happened to be away at the time, and what Bethe needed was someone to talk to, to push his ideas against. Well, he comes in to this little squirt in an office and starts to argue, explaining his idea. I say, “No, no, you’re crazy. It’ll go like this.” And he says, “Just a moment,” and explains how he’s not crazy, I’m crazy. And we keep on going like this. You see, when I hear about physics, I just think about physics, and I don’t know who I’m talking to, so I say dopey things like “no, no, you’re wrong,” or “you’re crazy.” But it turned out that’s exactly what he needed. I got a notch up on account of that, and I ended up as a group leader under Bethe with four guys under me.” (p. 112).

So the point wasn’t that, as Broad says, “Colleagues often balked” at Bethe’s ideas. The point is that most colleagues wouldn’t speak up the way Feynman did. When I first read Feynman’s account, I recalled Norman Eliason, a world-class medievalist I had the pleasure of working with at Chapel Hill. He was pushing me to do my dissertation on Anglo-Saxon metrics, as found in such Old English poems as Beowulf, and the experience was much the same as what Feynman encountered with Bethe. Although widely feared by graduate students, Eliason wanted to be challenged; he would lift his eyes to the heavens when you did so, and try to take you down a notch, preferably in a classroom setting. It was all part of the game. What he didn’t want was for you to back down (all too many did).

Bethe and Feynman were key players in the development of quantum electrodynamics (Feynman won a Nobel Prize for this work in 1965). We could use more of their provocative, inquiring spirit, unhampered by ego and any motive other than pure love for knowledge — what Feynman called ‘the kick in the discovery’ — wherever research is conducted on any subject.

Bethe’s output was legendary: “If you know his work,” said John Bahcall of the Institute for Advanced Study, delivering his own appreciation, “you might be inclined to think he is really several people, all of whom are engaged in a conspiracy to sign their work with the same name.” And anyone who’s getting up in years will admire a man who, at the age of 83, set about probing the immensely difficult lattice gauge theory, which deals with the transformation of nuclear materials into plasma at high temperatures. Much of his retirement, in fact, was devoted to the study of astrophysics.

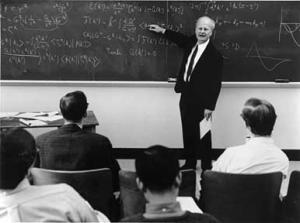

Finally, I note this wonderful description from Lee Edison’s 1968 profile of Bethe, as quoted in Broad’s obituary. Calling him “a tall, spare man with a deceptively distracted look,” Edison goes on to say:

“His graying hair seems permanently electrified; his shoes are scuffed, and his tie seems to have been studiously arranged to miss his collar button. He listens attentively, nodding his head as if in agreement, but – as devastated colleagues and adversaries have discovered – this habit is far from a sign of agreement. His ‘yes, yes, yes’ is rather a signal that his mental apparatus is receiving. What he does with the input is another matter.”

Cornell’s own press release on Bethe’s death is also worth reading. Bethe died in Ithaca at age 98. At his death he was emeritus professor of physics at Cornell, having joined the university in 1935 after fleeing Nazi Germany.