You would think that a star anywhere from 400 to 200,000 times wider than the Sun would be fairly easy to detect. But not if it’s a ‘dark star,’ the name for a new, theoretical entity about to make its appearance in Physical Review Letters. Astrophysicist Paolo Gondolo (University of Utah) makes the case that dark matter would have affected the temperature and density of the gases that formed the first stars. Dark stars would mostly contain normal matter — hydrogen and helium — but they would have been much larger than the Sun, glowing largely in the infrared.

So how would the early universe have produced a dark star? Gondolo looks at neutralinos, one type of the weakly interactive massive particles (WIMPS) that may explain dark matter. Calculating how dark matter would have affected the earliest stars, the team’s findings suggest that dark matter neutralinos would have annihilated each other, producing quarks and anti-quarks. A proto-stellar cloud trying to shrink into a star would encounter resistance as dark matter interactions kept it hot and large.

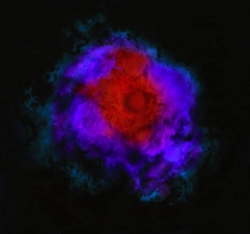

Image: This artist’s conception shows what an invisible “dark star” might look like when viewed in infrared light that it emits as heat. The core is enveloped by clouds of hydrogen and helium gas. A new University of Utah study suggests the first stars in the universe did not shine, but may have been dark stars. Credit: University of Utah.

“The heating can counteract the cooling, and so the star stops contracting for a while, forming a dark star,” some 80 million to 100 million years after the big bang, says Gondolo. “This is our main result.”

Imagine a ‘star’ as large as 2000 AU, large enough to hold 15,000 solar systems like ours. Such an object would throw off a host of interesting particles including gamma rays, neutrinos, positrons and antiprotons. Gondolo argues that these particles show characteristic signatures when derived from dark matter. The possible existence of dark stars, then, could help in the quest to identify dark matter in the early universe. Or perhaps the later universe, depending on how long such objects would survive, an issue that has not remotely been resolved.

When a theory like this emerges, the next step is to go to work looking for observational evidence. If objects of this sort exist, spewing gamma rays, neutrinos and antimatter, they may be detectable because they would be associated with cold, molecular hydrogen gas that wouldn’t be expected to produce such energetic particles. Or perhaps dark stars simply turn into conventional stars over time. The balance between dark matter heating and gas cooling inside the star would tell the tale.

I’m reminded of the hunt for something almost as preposterously exotic as dark stars. Wormholes may or may not exist, but observing a wormhole’s characteristic signature would produce the first hard data to make their reality convincing. A paper on just how to do that, by John Cramer and a team of collaborators, has already appeared, though the wormhole signature defined there has yet to be seen (more on this later). Will dark stars ever generate the kind of observational anomaly that turns this unusual theory into a true revision of stellar evolution?

This idea of dark matter stars reminds me of a passage from Robert W Chambers’ The King In Yellow:

And here I was thinking that I was the only one around who still read Chambers! The King in Yellow, by the way, is available via Project Gutenberg for those who haven’t sampled it:

http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/8492

On the other hand, I love my old beat-up, non-electronic edition…

I wonder if there are such stars as blackstars but not in the blackhole sense, nor in the nuetron star sense or cooled white dwarf sense. I am referring to Ultra Violet Stars. Such stars if they exist would have elemental composition and perhaps some type of dark matter wherein their mass would be so large that their surface temperature would be on the order of 0.5 million K or so and so would radiate away in the extreme ultraviolet soft x ray spectrum. Given the T EXP 4 dependance on total integrated spectral emmisions for an ideal blackbody, the star would have to have a great deal of matter and have some way of settling down to shine after the contraction of its precursor protostar and then a means to suddenly start shining very hotly without blowing itself apart nor shedding its outer layers to quickly as a result of thermal expansion and escape of the outer layers of the star.

Thus, the escape velocity at the surface of the star would need to be very high thus presumming a relatively compact star. I can imagine that a surface escape velocity on the order of 2,000 km/sec to 3,000 km/sec would be required to hold the surface gas in for any significant length of time.

Now I have heard of Blue Super Giant Stars with surface temperatures of perhaps at most 50,000 K, but the bad boys I am referring to above would emit 10,000 times the power per unit surface area than a blue super giant would. I imagine that such stellar bodies would be rare freaks but fascinating ones nonetheless. They might make excellent sources for powering locally manufactured and launched interstellar space craft, locally to the black star that is.

Jim

Small “helper” stars needed for formation of massive stars,

UC Berkeley, Princeton researchers report

http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=24862

“In order for a rare, massive star to form inside an interstellar

cloud of gas and dust, small “helper” stars about the size of the

sun must first set the stage, according to a new theory proposed

by astrophysicists at the University of California, Berkeley, and

Princeton University.”

Well if there could be dark matter stars could there be dark matter planets etc