By Larry Klaes

Apropos of yesterday’s story on the possible cometary origin of the Tunguska Event in 1908, Tau Zero journalist Larry Klaes looks at the NExT (New Exploration of Tempel) mission, which gives us a second crack at observing comet Tempel 1. Ancient artifacts of the early Solar System, comets can tell us much about its earliest days, but as Larry points out, getting data out of the Deep Impact mission proved to be unexpectedly complicated. NExT is a useful re-purposing of an earlier mission that may unlock further cometary secrets when it returns to Tempel 1 in 2011. If a comet did cause Tunguska, here’s hoping such events continue to be rare, but in the meantime, garnering all the information we can about how comets are made is as important for planetary security as it is for the study of Solar System origins.

An Impact to Remember

Late on the Fourth of July in 2005, while fireworks brightened the sky across the United States, another group of American citizens were making another type of explosion millions of miles away on a small alien world, a form of fireworks being done in the name of science. A robotic space probe, aptly named Deep Impact, lobbed a heavy copper ball at an ancient comet called Tempel 1, smashing into its surface and creating a crater over 300 feet across and almost 100 feet deep in the icy crust.

Mission members had hoped to peer into the crater they made with Deep Impact’s camera eyes to study the deeper and therefore older layers of Tempel 1’s surface. However, they were surprised to discover that the debris kicked up from the impact made a very fine dust cloud that hovered over the crater long after Deep Impact had left the vicinity of the comet, heading back into interplanetary space.

Image: Deep Impact’s impactor collides with Tempel 1. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Inventing a New Mission

Meanwhile, another comet probe named Stardust was winding its way back home after successfully collecting particles from an ice ball named Wild 2 over one year earlier. Stardust would return those priceless samples of an alien world to Earth in early 2006 using a small capsule craft. Then Stardust, its primary mission complete, would swing back out into the void, presumably forever.

Thus the dilemma: Deep Impact had not been able to image the crater it made on Tempel 1 as originally planned and could not return to that comet, while Stardust became a still-functioning spacecraft with plenty of onboard fuel, but with nowhere to go. So some clever folks with the US space agency proposed to reroute Stardust to see what its sister vessel had actually done to Tempel 1 and achieve some other important science goals. NASA approved this mission on July 3, 2007 and Stardust was rechristened NExT, which stood for New Exploration of Tempel 1.

Though NExT will not encounter its cometary target until Valentine’s Day in 2011, mission scientists are already hard at work planning every little detail of the space probe’s one shot at Tempel 1 less than two years from now. Scientists from all over the country met at Cornell University on June 8 and 9 to discuss NExT with the astronomy department’s Joe Veverka, who is the Principal Investigator, or PI, for the mission and a veteran of space expeditions throughout the Solar System.

A New View of a Cometary Crater

One of those who traveled far to be at this meeting was H. Jay Melosh, a professor of planetary science at the University of Arizona at Tucson. A former member of the Deep Impact team, Melosh is a renowned expert on impact cratering and is naturally quite interested to see what that probe did create on the surface of Tempel 1 almost four years ago.

“We want to get there when the crater made by Deep Impact is in view of NExT’s cameras,” says Melosh, who also emphasizes the importance of precisely timing when the robot explorer would fly by the comet. NExT will be moving so fast on its arrival day that the space probe will zip past Tempel 1 in just 20 minutes.

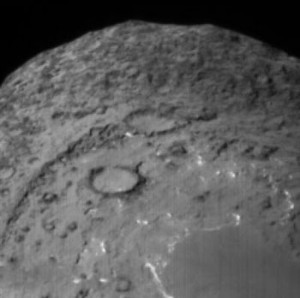

Image: Comet Tempel 1 just ninety seconds before the 2005 impact. The image was taken by the targeting sensor on Deep Impact’s impactor. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UMD.

Melosh and his team members also want to see how the comet’s surface may have changed both from the Deep Impact probe crash and natural cosmic effects during its five year orbit around the Sun. Although Tempel 1 is a fairly quiet comet compared to some of its more geologically active brethren, professional astronomers from around the globe monitoring Tempel 1 have noted that its 42-hour rotation rate has changed since humans first visited that little world in 2005. Melosh wants to know exactly how fast the comet is spinning on its axis now and when NExT arrives in 2011.

“Comets vent gas all the time,” explains Melosh, “so they have changing rotation rates as a result. Tempel 1 is a low activity comet, but its rotation rate still changed.”

On to Another Battered World

Though Melosh is now a geophysicist at his university’s Lunar and Planetary Lab (LPL), his first college degree from Princeton was in physics. When he attended Caltech in the early 1970s as a graduate student, Melosh became interested in glaciology and Earth science. He also got a chance to participate in the Mariner 10 space mission, the first vessel to encounter the planet Mercury. Melosh became fascinated with impact craters, which are widely found on this smallest of our system’s terrestrial worlds, during that time.

The scientist plans on exploring another battered celestial object in the near future with a mission labeled GRAIL, which stands for Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory. Launching the same year that NExT encounters comet Tempel 1, GRAIL consists of two identical craft that will study our Moon’s gravity field in detail both for science and to assist future lunar spacecraft navigating our neighboring world.

Lots of rubbish have been written about comets – that they’re dry and subject to arc discharges, that they harbour colonies of photosynthetic plants, and so on. My favourite is Edward Drobyshevski’s suggestion that they’re produced by explosions on the surfaces of ice moons. It seems that solid-state electrolysis can occur, with the ices decomposing into H2 + O2, trapped in the ice and then eventually reaching an explosive mixture level, before being triggered by an impact. No one disputes the electrolysis can occur but the storage of H2 has been doubtful in the fragmented ice breccia of icy moon crusts. If NExT finds a bigger crater than expected then maybe Drobyshevski is right, in which case landing on ice moons with hot exhaust jets will need to be a careful business…

http://www.technologyreview.com/blog/arxiv/23784/

Wednesday, July 01, 2009

Comets Seeded Earth’s Early Atmosphere

The ratio of nitrogen isotopes in several comets almost exactly matches the ratio on Earth, implying that our early atmosphere probably came from a cometary bombardment.

Astrobiologists have long puzzled over the origin of Earth’s oceans. But they’ve dwelt a little less long over a related question: where does the nitrogen in our atmosphere come from?

Now a new analysis by Damien Hutsemekers and pals at the Universite de Liege, in Belgium, suggests an answer to both questions.

One of the most attractive theories of the origin of our water is that Earth was once bombarded by icy comets that left a watery residue. The trouble is that the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen in water on Earth is much lower than it is in the few comets we’ve been able to measure it in (i.e., Halley, Hyakutake, Hale-Bopp, and C/2002 T7 LINEAR). So if these types of comets, which we know came from the Oort Cloud, did supply Earth’s water, it must have mixed with water already on Earth that had a very low deuterium content.

Now Hutsemekers and co have put a different kind of constraint on the cometary contribution by measuring nitrogen isotopes. They say that comets must deliver water and nitrogen together (although they don’t say why), so a comparison of nitrogen isotopes can also place limits on the amount of water that must have been delivered.

Their conclusion is that “no more than a few percent of Earth’s water can be attributed to comets.”

But that’s not the end of the story. Interestingly, they say that the ratio of nitrogen-14 to nitrogen-15 in cyanide and hydrogen cyanide in comets almost exactly matches that on Earth. “A significant part of Earth’s atmospheric nitrogen might come from comets,” they conclude.

That’s any exciting result because it implies a dual origin for our oceans and atmosphere.

Of course, the huge fly in this hypothetical ointment is that there may well be other types of comet out there that have hydrogen to deuterium ratios as well as nitrogen isotope ratios that more closely match our own.

But in the meantime, the idea that comets gave us our early atmosphere is cool enough to keep us a-wonderin’ for a while.

Ref: http://arxiv.org/abs/0906.5221: New Constraints on the Delivery of Cometary Water and Nitrogen to Earth from the 15N/14N Isotopic Ratio

August 17, 2009

Amino Acid Found in Stardust Comet Sample

Written by Nancy Atkinson

NASA scientists studying the comet samples returned by the Stardust spacecraft have discovered glycine, a fundamental building block of life. Stardust captured the samples from comet Wild 2 in 2004 and returned them to Earth in 2006.

“Glycine is an amino acid used by living organisms to make proteins, and this is the first time an amino acid has been found in a comet,” said Dr. Jamie Elsila of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“Our discovery supports the theory that some of life’s ingredients formed in space and were delivered to Earth long ago by meteorite and comet impacts.”

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/2009/08/17/amino-acid-found-in-stardust-comet-sample/