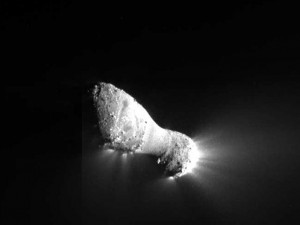

The Hartley 2 flyby was an outstanding event, and the only thing I regret about my recent travels was that I was unable to follow the action as the images first streamed in. By now, sights like the one at left have made their way all over the Net, so I won’t dwell on them other than to say that if you haven’t seen the short video clip of the EPOXI flyby, you should definitely give it a look. You’re getting the view from a spacecraft that closed to 700 kilometers or so of the surface, during an encounter taking place at a speed of 12.3 kilometers per second.

Image: Comet Hartley 2 can be seen in glorious detail in this image from NASA’s EPOXI mission. It was taken as the spacecraft flew by around 6:59 a.m. PDT (9:59 a.m. EDT), from a distance of about 700 kilometers (435 miles). Jets can be seen streaming out of the nucleus. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UMD.

I’ll go along with EPOXI principal investigator Michael A’Hearn’s description of the comet’s “stark, majestic beauty.” Interesting to learn that Hartley 2 has a hundred times less volume than comet Tempel 1, which was Deep Impact’s first target, but there’s plenty still to learn from the data that streamed in from 37 million kilometers away. Adds A’Hearn (University of Maryland, College Park):

“Early observations of the comet show that, for the first time, we may be able to connect activity to individual features on the nucleus. We certainly have our hands full. The images are full of great cometary data, and that’s what we hoped for.”

Thus we get the most extensive observations of a comet in history. This is the first time that two comets have been imaged by the same spacecraft and at the same spatial resolution. What next for Deep Impact and the EPOXI mission? Interestingly, the spacecraft has enough usable fuel, about four kilograms, to support continued science observations even after the Hartley 2 flyby. We’ll have to see whether tasking it with a new assignment is in the cards.

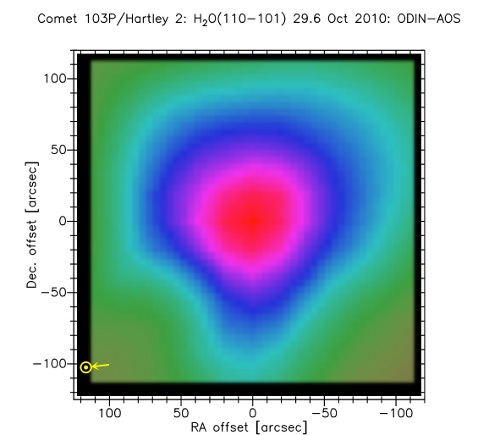

Hartley 2 has been under scrutiny from other sources as well, including the Odin satellite, a Swedish spacecraft created in collaboration with Canada, Finland and France. Odin studied Hartley 2 at the end of October and was able to detect its water signature line at 556.9 GHz with ease, as shown in the image. The rapid variations in water production are thought to be related to the rotation of the comet’s nucleus. Water vapor is released as the cometary nucleus is heated by the Sun — recall that Hartley 2 passed perihelion as recently as 28 October.

Image: A map of water in Comet Hartley 2, observed by Odin on 29 October 2010. Copyright 2010 Swedish Space Corporation/Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales/Observatoire de Paris.

With Hartley 2 creating a celestial display as cometary dust burns up in the Earth’s atmosphere (the comet passed within 19 million kilometers of our planet on 20 October), this is a comet we’ll long remember. Unfortunately, for me it’s associated with a long airline flight and a developing cold that settled in halfway home. It’s amazing how someone who writes so much about going to the stars dislikes all aspects of travel, but it’s the truth, and that reminds me of a story.

Some years back I talked with Bob Forward, Robert Forward’s son, about his late father. The elder Forward was, of course, a towering figure in interstellar studies, changing our perception of what is possible in terms of delivering payloads to other star systems. Bob told me that one night he asked his father this question: If an alien spacecraft landed on the front yard and you were invited to go out into the universe, with the proviso that you could never come back, would you go? And Robert Forward answered instantly (to the dismay of wife Martha), “Of course!”

Consternation reigned. Would Forward really leave his family behind to go to the stars? Well, yes. “You have to understand,” he went on to say. “This is what I have dreamed about all my life.”

I love the story, but I can only say that I’m on a different page. If the spacecraft lands, I’m all for somebody getting on board, but it won’t be me. What I do hope is that whoever goes has some way to get data back to Earth so I can write the story here. This morning, fighting a fever and a sore throat, nursing a lemon-and-honey hot toddy, I’m thinking that home has its charms, and I’m about ready to get back into bed.

Ha. I’ve got that same bug too. And the citron drink.

It’s too cold in space. Those long hard journeys may be a job for young men. Like soldiering.

Tarmen, you are so right! Ah, for a sturdier constitution and a few less years…

Get well soon, and thanks for all the work you do on this site.

Thank you, Istvan. I’m feeling much better as the day progresses :-)

The Fermi Question is now joined by the Forward Question: Where are they? Why, they’re here. Want to go?

If anyone has Centauri dreams, then they should be prepared to answer it, no hesitation. For myself, Forward’s answer sufficies. Of course, I want to make sure I wouldn’t wind up in a stew pot at the other end (the old “To Serve Man” scenario), but after my questions are answered satisfactorily (the alien equivalent of the Turing Test — anyone want to come up with questions for that?), I would be on my way faster than you can say “Steven Hawking.”.

Has anyone else been entranced by the image of Hartley? The center section is much more smooth than the ends and looks like a section that is being stretched like a glacier. Could it pull apart eventually from the effects of the rotation?

The Fermi paradox:

http://www.astrobio.net/pressrelease/3661/the-universal-need-for-energy

http://sites.bio.indiana.edu/~bauerlab/origin.html

I think planets with free Oxygen atmospheres are rare.

Of course ET might be more interested in settling down here after travelling all that way.

What a job of interplanetary driving! I’m stunned really by those space jockeys able to hit such a small target, so far away, and at huge speeds. And do it reliably.

Paul, my dear — here’s wishing you a big Get Well Soon. Owing to the fact that i’m way behind in my reading, you are probably already well. Just had to say it!

Connie, I am much improved — another day or so should do it. Many thanks for your kind thoughts!