Planetary migration can play a huge role in the evolution of a solar system, as witness the thinking that it was a migration of the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn that brought about the Late Heavy Bombardment, a time four billion years ago when impacts from space pock-marked the Moon and inner planets. The migration model, first proposed at the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur and thus known as the Nice model, posits a long-lasting cometary bombardment caused when gravitational effects of the migration scattered icy bodies in the Kuiper Belt. Most of these would have been ejected from the system, but others would have been sent on planet-intersecting paths.

If the Nice model is correct, then we may have an explanation for at least part of the water that wound up on our blue and green planet today, with obvious consequences for the development of life. That makes events similar to the Late Heavy Bombardment of considerable interest when we can find them in other solar systems, and new work with Spitzer Space Telescope data says we’ve now done just that. The nearby bright star Eta Corvi is the site of a band of dust that shows up with the help of Spitzer’s infrared detectors. The star is approximately one billion years old, young enough to mimic what we believe was the situation around our own Sun in that era.

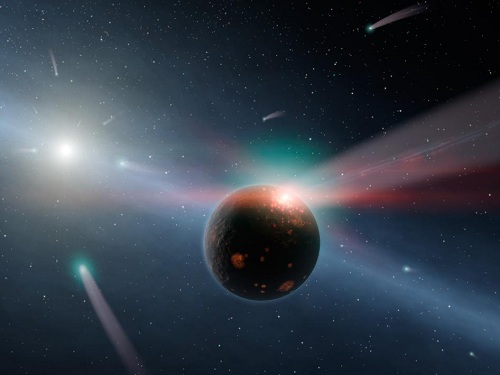

Image: This artist’s conception illustrates a storm of comets around a star near our own, called Eta Corvi. Evidence for this barrage comes from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, whose infrared detectors picked up indications that one or more comets was recently torn to shreds after colliding with a rocky body. In this artist’s conception, one such giant comet is shown smashing into a rocky planet, flinging ice- and carbon-rich dust into space, while also smashing water and organics into the surface of the planet. A glowing red flash captures the moment of impact on the planet. Yellow-white Eta Corvi is shown to the left, with still more comets streaming toward it. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

What we see around Eta Corvi is telling. The researchers found evidence in the dust disc of water ice, organics and rock, all of which indicate a cometary source. From the paper:

We interpret this as demonstrating that the parent body for the ? Corvi warm circumstellar dust was a large object created early in the system’s history, that it formed outside the ice line of the ? Corvi system, and that it retained much of its icy volatiles and primitive material.

Moreover, the dust band in question is close enough to Eta Corvi that Earth-like planets could exist there, leaving the implication that we’re looking at the results of a collision between a planet and one or more comets. Is this what our own Solar System might have looked like during the Late Heavy Bombardment? It’s a distinct possibility. Lead author Carey Lisse (JHU/APL): “We believe we have direct evidence for an ongoing Late Heavy Bombardment in the nearby star system Eta Corvi, occurring about the same time as in our solar system.”

Two bands of dust surround Eta Corvi, the second being a much colder ring at about 150 AU in a region that bears obvious analogies to our Kuiper Belt and may be a reservoir for comets. It’s intriguing that the light signature emitted by the inner Eta Corvi dust band resembles the composition of the Almahata Sitta meteorite, fragments of which were recovered in the Sudan in 2008. The Kuiper Belt may well have been the origin of the Almahata Sitta object. Eta Corvi thus becomes a wonderful laboratory for the study of cometary bombardment because it contains both warm and cold dust reservoirs with strong spectral features, and its rarity may itself be telling us something, as the paper goes on to note (internal references omitted for brevity):

Large photometric studies of many debris disks and targeted spectroscopic studies of individual debris disks conducted with the Spitzer Space Telescope have constrained the typical locations of debris-producing collisions, the evolution of the emission from these collisions, and, in some cases, the chemical composition of and events identified by the colliding parent bodies. Most debris disks have dust temperatures colder than ~ 150—200 K, consistent with debris produced from icy colliding planetesimals… The frequency of warm (> 200 K) debris dust is low, < 5—10% regardless of age, indicating that planetesimal collisions in the terrestrial zone or asteroid belt-like regions are rare or have a small observational window, consistent with expectations from theory...

That small observational window would certainly fit current thinking about the Late Heavy Bombardment as a period of intense activity that moderated following planetary migration. In any case, debris disks around young stars are proving their worth, suggesting as they do a reservoir of colliding planetesimals. Our own more mature system, of course, has two belts — relatively warm dust and metal-rich bodies in the asteroid belt between 2 and 4 AU and the cold dust and icy planetesimals of the Kuiper Belt beyond 30 AU. By studying such discs around other stars, we are looking at system evolution in action and learning more about our system’s past.

The paper is Lisse, et al., “Spitzer Evidence for a Late Heavy Bombardment and the Formation of Urelites in ? Corvi at ~1 Gyr,” accepted by the Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

The Hadean period is what the heavy bombardment period is called. An appropriate name.

The Hadean period? That is an extremely appropriate name- Hades’ realm is cold and dark, just as comets are; the collisions are hot and violent, just as fire exists in Hades’ realm beneath the Earth, and these collisions bring a wealth of resources- rock, water ice, organic molecules, etc.

It would be a fantastic journey to get up close to a comet as it swung in toward the sun, land on it, and ride it on its way back out. I’d want some good shielding so my craft would not be damaged by debris flung off of the comet. It might be a long trip, though- comets take years to swing out and return. Perhaps it would be best to simply tour the comet and then return to Earth.

Comet storms might have brought water to Earth a long time ago, but I don’t think we would want another series of comet storms to start. An object wandering too close to our solar system might disturb the Kuiper Belt and send a comet storm to Earth. This would possibly end civilization. Too many people think of these scenarios as merely science fiction, if they think about them at all. Watch those skies…

Bracing conditions for planet dwellers, to be in such a system, but for free space inhabitants such a system would be a precious jewel.

Eta Corvi is another addition to the set of evidence that includes the Late Heavy Bombardment in our own solar system and the huge volumes of dust around the several Gyr old binary BD+20 307 that indicates that even relatively old planetary systems can undergo extremely violent events. Some of the instabilities evidently take a long time to tease out.