Imagine what we could do if we could attain speeds of 640 kilometers per second. That’s the velocity of a comet recently tracked just before passing across the face of the Sun and apparently disintegrating in the low solar corona. I’m just musing here, but it’s always fun to muse about such things. 640 kilometers per second drops the Alpha Centauri trip from 74,600 years-plus (Voyager-class speeds) to less than 2000 years. A long journey, to be sure, but moving in the right direction, and in any case, these are speeds that would allow exploration deep into the outer system. We’re a long way from such capabilities, but they’re a rational goal.

But back to the comet. The object was discovered on July 4, 2011 and designated C/2011 N3 (SOHO), the latter a reference to the ESA/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, whose Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph made the catch. On July 6, NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory was able to pick up the comet some 0.2 solar radii off the Sun, where it was tracked for a mere 20 minutes before evaporating some 100,000 kilometers above the solar surface. The Extreme-Ultraviolet Imager aboard one of NASA’s Solar-Terrestrial Relations Observatories (STEREO) was also able to observe the comet, allowing researchers to get a good read on its makeup, as the lead author of the paper on this work, Karel Schrijver (Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory), points out:

“This unprecedented passage of a comet through the solar atmosphere in view of our AIA cameras [the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly aboard the SDO] presented us with a remarkable opportunity. As we witnessed this comet evaporate as it traversed a known amount of space over a specific period of time, we were able to work backward to estimate its mass just before it reached the Sun. We’ve been able to bracket its size as between 150 and 300 feet long, with a greater likelihood that it lies at the upper end of that range. And it most likely weighed in at as much as 70,000 tons, giving it about the weight of an aircraft carrier, when it first became visible to AIA.”

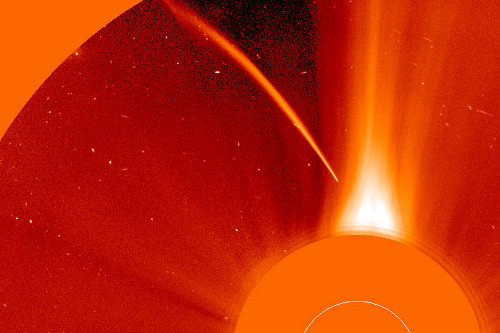

Image: Although it’s not C/2011 N3, this Sungrazer was also destroyed, its fiery fate recorded by the SOHO spacecraft’s Large Angle Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO) on December 23, 1996. LASCO uses an occulting disk, partially visible at the lower right, to block out the otherwise overwhelming solar disk allowing it to image the inner 5 million miles of the relatively faint corona. The comet is seen as its coma enters the bright equatorial solar wind region (oriented vertically). Spots and blemishes on the image are background stars and camera streaks caused by charged particles. Credit: LASCO, SOHO Consortium, NRL, ESA, NASA.

In addition to the image above, images of the ‘string of pearls’ comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 breaking apart before impact with Jupiter in 1994 inevitably come to mind, especially when we learn that C/2011 N3 likewise broke into a series of large chunks ranging up to 45 meters in size as it began to disintegrate. The comet’s coma — the envelope of ice, dust and gas surrounding its nucleus — is thought to have been some 1300 kilometers across, with a cometary tail approximately 16,000 kilometers long. The breakup of the comet was further flagged by pulsations in the brightness of the tail, a phenomenon Schrijver’s team was able to put to good use:

“I think the light pulses in the tail were one of the most interesting things we witnessed,” said Schrijver. “The comet’s tail gets brighter by as much as four times every minute or two. The comet seems first to put a lot of material into that tail, then less, and then the pattern repeats. Only because of these pulses can we measure how fast the tail falls behind the comet as its gases collide with those in the Sun’s atmosphere. And that, in turn, helps us measure the comet’s weight.”

A cometary demise is a spectacular event, but it turns out that the SOHO spacecraft has observed more than 2000 comets as they approached the Sun. The so-called Kreutz Sungrazers are comets whose orbits take them within one to two solar radii of the photosphere every 500 to 1000 years. This is the largest known group of comets, one which is thought to have resulted from the breakup of a massive progenitor body several thousand years ago. The smaller Kreutz group comets rarely survive perihelion. While the SOHO observatory now tracking a Sun-grazing comet on an average of once every three days, those that make it into the solar corona should be useful tools for extending our knowledge of cometary properties.

The paper is Schrijver et al., “Destruction of Sun-Grazing Comet C/2011 N3 (SOHO) Within the Low Solar Corona,” Science Vol. 335 no. 6066 pp. 324-328 (20 January 2012). Abstract available.

What gave it this spectacular velocity?

Paul Gilster said in the main article:

“While the SOHO observatory now tracking a Sun-grazing comet on an average of once every three days, those that make it into the solar corona should be useful tools for extending our knowledge of cometary properties.”

So if we can detect at least one comet every three days plunging towards the Sun, why aren’t we seeing more of them in our skies? And what does this say about the odds of Earth and other main Sol system bodies being hit by one? Especially as these kinds of comets only appear in our vicinity once every 500 to 1,000 years on average, as you say. Is space just that big, or have we just been that lucky? Or both?

Greg, my guess would be that velocity is simply that gained from falling this deep. Not useful for travel, really, as it must be given up again upon climbing back out the gravity well.

if we can direct this comet to impact venus and trigger ice-age there, maybe we can make venus habitable.

Nah… just weird idea of mine :D

ljk, nearly all of these comets are much smaller than the comets we can see further away from the sun. Many are smaller than Tunguska sized objects, which hit our planet every century or so (as compared to the millions of years between being hit by comets large enough to detect further out).

I’m curious as to how close these objects actually correspond to the family of objects we call “comets” further out in the solar system. If a perfectly dry asteroid got blasted by such a larger flux of solar energy, wouldn’t it also start to lose its surface regolith and produce a tail? What do spectroscopy studies say? (The long periods of the orbits do, of course, strongly suggest that the objects are indeed full of volatiles).

Solar surface escape velocity is 617.5 km/s. So Dr. Benford a has made a significant observation. If the comet’s velocity was reported accurately, it had even more kinetic energy than it would have gained by falling down Sol’s gravity well. It may have drifted into the Sol system from the Oort cloud of another star, or gained energy from a Jovian flyby.

@Greg

Yeah that’s greater than escape velocity from the Sun.

It can’t have gotten a hyperbolic excess from Jupiter since it is Kreutz group I and has an inclination of 144 degrees.

I don’t know about non gravitational perturbations from out gassing,

seems unlikely.

The Kreutz group are the largest number of sungrazers , almost 1400 observed in group I now.

Thought to come from a 200 km progenitor that seems to have split into two super fragments after a really close encounter with the Sun, maybe 2000 or so years ago.

Ikeya–Seki was a Kreutz group comet.

The Kreutz group progenitor may have been a Centaur object. These are Cis-Neptunian objects on chaotic orbits which makes most into Jupiter crossers , they are either ejected into from the solar system or into the inner Solar System!

2060 Chiron , 233 km in size may be swimming in rocky planet space in a few million years, that would be interesting to see!

Object 10199 Chariklo is nearly 260 km in size and may be in here in 10 million years.

I would worry more about Yellowstone.

Joy said on January 20, 2012 at 8:04:

“Solar surface escape velocity is 617.5 km/s. So Dr. Benford a has made a significant observation. If the comet’s velocity was reported accurately, it had even more kinetic energy than it would have gained by falling down Sol’s gravity well. It may have drifted into the Sol system from the Oort cloud of another star, or gained energy from a Jovian flyby.”

There is my next question: Have we yet detected any comets, planetoids, or KBOs/TNOs that have orbits which clearly indicate they came from outside our Sol system, even beyond the farthest reaches of our Oort Cloud?

And have any of them suddenly started braking? ;^)

Picking up on Joy’s (elaboration of Dr. Benford’s) point. I think she’s right. Correct me if I’m wrong, but … With the possible exception of an object that received a gravitational boost from a large planet, we should not be seeing ANY object inside the Solar System moving faster than solar escape velocity at any given distance from the Sun. By definition, any objects exceeding this velocity should have already been ejected from the Solar System, unless they originated outside of it.

If the comets tail is heating up much faster than the comet, and represents a very large fraction of its mass, could this push it along? Whatever the mechanism, Benford is right, such huge hyperbolic excesses (at the very least170 km/s, and way more than Jupiter can offer) occurring naturally must offer prospects that we may be able to build a rough and ready deep space probe that can also achieve such speeds.

In reading this latest entry into Centauri dreams an idea occurred to me which could seem preposterous on its surface but could actually have some merit insofar as it being able to be accomplished. So please don’t laugh until you heard me out.

The idea is simply this: intercept the comet when it still pretty far from the sun, maybe Neptune or something like that, with the spacecraft that in some fashion can attach itself to the cometary body. I’m well aware of the fact that there is an enormous difference in velocity vectors between the spacecraft and the comet but entertain the notion that it can be done. Once attached the spacecraft could be shielded by the cometary or asteroidal body as it swings around the sun protected from the intense heat. Once on a outward bound journey it would obtain solar escape velocity. Choosing the right celestial body could permit a detachment of the spacecraft at the appropriate moment to give it a velocity vector outward to a target star.

@ljk

“There is my next question: Have we yet detected any comets, planetoids, or KBOs/TNOs that have orbits which clearly indicate they came from outside our Sol system, even beyond the farthest reaches of our Oort Cloud?”

This is a good question. Back when I was doing planetary science several researchers over the years have studied the catalog of long period comets, these are the comets of most interest.

I don’t know what has been found in recent years , but an extensive study in 2005 found there is not a single ‘interstellar’ comet in long period comet catalogs. (1) We know they are there because the long term evolution of the Oort cloud shows that over the solar systems lifetime almost 90% of the Oort cloud that originated at the ‘last scattering’, before the solar system settled down , have been ejected into the Galaxy. Which means if planet formation proceeds as we think, other planetary systems should have ejected gobs of comets. The data from the study in [1] shows the interstellar comet density in the Sun’s vicinity is about 4.5×10^?4/AU^3.

There comets in the catalog unbound from the Sun, but these are guys who maybe gravitational swingbys of Jupiter that got ejected.

There should be billions of ‘interstellar’ planets too, thankfully the Sun seemingly has not seen one of these over it’s life time. (Shades of Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer!)

[1] Francis, Paul J. (2005-12-20). “The Demographics of Long-Period Comets”. The Astrophysical Journal 635 (2): 1348–1361.

@ljk:

While objects large enough to be classed as comets or asteroids have not (to my knowledge) been found yet, there does seem to be some evidence for a stream of interstellar meteoroids originating in the direction of Beta Pictoris.