I’m not surprised that Michael Chorost continues to stimulate and enliven the SETI discussion. In his most recent book World Wide Mind (Free Press, 2011), Michael looked at the coming interface between humans and machines that will take us into an enriched world, one where implants both biological and digital will enhance our experience of ourselves and each other. You’ll recall that it was a cochlear implant that restored hearing to this author, and doubtless propelled the thinking that led to this latest book. And it was the issue of hearing and communication that we looked at in an earlier discussion of Chorost’s views on SETI.

That conversation has continued in Michael’s World Wide Mind blog, as he ponders some of the comments his earlier ideas provoked on Centauri Dreams. In particular, how would we ever come to understand an extraterrestrial civilization if it differed fundamentally from us? Chorost thinks the problem is not biological, that no matter how aliens might look, we could study them to understand how they function. What would be far more tricky are questions of technology and culture, and here he brings into play Ken Wilber’s ideas about evolutionary development, notions that can be summarized in the chart immediately below.

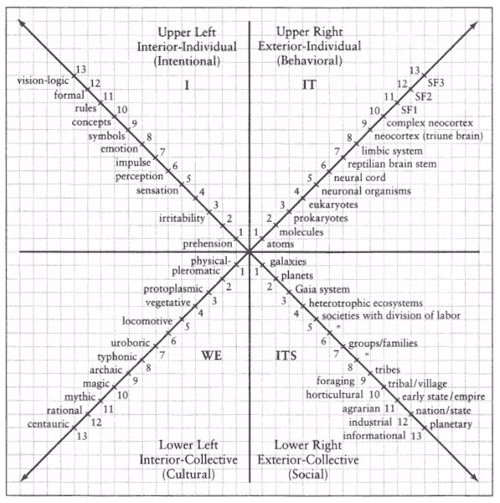

Image: Based on Ken Wilber’s ideas of an ‘all-quadrants, all-levels’ model of evolutionary development, this chart shows four axes that trace the development of a society. Credit: Ken Wilber via Michael Chorost.

If you browse through the diagram, you’ll note the likelihood that a society at level 10 on one axis will be at level ten on the other three. Chorost explains:

For example, level 10 in the upper-left quadrant is conceptual thinking. It’s aligned with level 10 in the other quadrants, which are the complex neocortex, the tribe/village, and magical modes of thought. When brains developed complex neocortexes, that was when they were able to sustain the social structures of tribes and villages, along with rituals of propitiation. One could also put it the other way around: tribal structures facilitated the development of the modern neocortex. These are all intimately related and mutually constituting. Each level on each axis is dependent upon, and enables, the others.

All of which seems to make sense, but what we should be pondering are the implications of extending each axis indefinitely. An advanced extraterrestrial species could easily register well beyond 10 on the chart along all four axes, making our need to relate human experience to what we encounter that much more difficult. We may, in fact, lack the neural structures to conceptualize and analogize these advanced levels because an alien culture would have developed modes of thought based on its own experience that are too remote from our more limited grid.

It’s always fascinating to portray encounters with aliens and always a bit aggravating when they show up in Hollywood as clearly human with a few tweaks to make them seem different. But even as we fuss with the producers of such shows for their lack of imagination (or budget), we’re missing the bigger picture. The problem is that we may find our galactic neighbors to be incomprehensible on every level. Here I think, as I often do, of the Strugatsky brothers’ novel Roadside Picnic, in which alien visitors have no apparent interest in humans at all, leaving behind them artifacts that no one can figure out. Their presence tells us that we are not alone, but their departure leaves us with questions of intent — what was their purpose here, and what are the ’empties’ (the book’s term for artifacts) that the aliens have abandoned?

In fact, Roadside Picnic gets across the sense of the inexplicably alien better than almost any novel I have ever read — it should definitely be on the short-list for Centauri Dreams readers. The so-called ‘Visitation’ in the novel involves six different places where the aliens appeared, though they were never actually seen by people living nearby. The ‘zones’ of visitation are filled with unusual phenomena and bizarre items like the ‘pins’ found by the protagonist, who is himself a ‘stalker’ who finds and sells alien oddities like these:

In the electric light the pins looked shot with blue and would on rare occasion burst into pure spectral colors — red, yellow, green. He picked up one pin and, being careful not to prick himself, squeezed it between his finger and thumb. He turned off the light and waited a little, getting used to the dark. But the pin was silent. He put it aside, groped for another one, and also squeezed it between his fingers. Nothing. He squeezed harder, risking a prick, and the pin started talking: weak reddish sparks ran along it and changed all at once to rarer green ones. For a couple of seconds Redrick admired this strange light show, which, as he learned from the Reports, had to mean something, possibly something very significant…

But what? The novel is shot through with ambiguity and mystery. It’s the mystery of Wilber’s diagram extended indefinitely in all four directions, assuming structures of thinking that may be so far beyond our experience as to defeat our every inquiry. In human terms, we can imagine the difficulty in trying to explain sunset colors to a color-blind person. Chorost uses a much better example: The difference between a non-literate society and a literate one. Could science develop in the absence of a written language in which to couch its arguments and record its findings? And just how you would explain these questions and the need to perform these functions with language to someone who had never experienced reading or writing?

It’s possible to see ways around these problems, as Chorost explains:

I’d like to be optimistic. I’d like to think we’d be better off than preliterates puzzling over Wikipedia on an iPad. In his book The Beginning of Infinity, David Deutsch argues that humans crossed a crucial threshold with the scientific method. We now know that everything is explainable in principle, if we make the effort to understand it. Arthur C. Clarke famously said that any sufficiently advanced technology will seem like magic. This may be true, but we will not mistake it for magic. We have a postmodern openness to difference, a future-oriented culture, and well-established methodologies for studying the unknown. Our relative horizons are much larger than our ancient ancestors’ were.

I’m a bit more ambivalent. Yes, we would make every effort to explain an extraterrestrial culture. But I think that even our best methodologies will have trouble untangling motives and intent if confronted with a civilization substantially older than our own. The solution may not be in our hands but theirs (if they have hands). How concerned will they be in establishing a relationship with us? In the Strugatskys’ novel, the aliens have come and gone, leaving behind them little more than enigma. Roadside Picnic gives us a glimpse of what an extraterrestrial encounter may be like unless the culture we meet finds us worth the effort to introduce itself.

AI computer pioneer Marvin Minsky wrote a paper in 1985 addressing the very issue of whether humans and an alien intelligence could understand each other.

Minsky says yes based on the fact that intelligence has to have certain common parameters regardless of where a mind may have evolved or in what body it may be housed.

The article is online here:

http://web.media.mit.edu/~minsky/papers/AlienIntelligence.html

To quote from the beginning of his piece:

“Communication with Alien Intelligence”

Marvin Minsky

In memoriam: Hans Freudenthal

Published in Extraterrestrials: Science and Alien Intelligence (Edward Regis, Ed.) Cambridge University Press 1985. Also published in Byte Magazine, April 1985.

“When first we meet those aliens in outer space, will we and they be able to converse? I’ll try to show that, yes, we will–provided they are motivated to cooperate–because we’ll both think similar ways.

“My arguments for this are very weak but let’s pretend, for brevity, that things are clearer than they are. I’ll propose two reasons why aliens will think like us, in spite of different origins.

“All problem-solvers, intelligent or not, are subject to the same ultimate constraints–limitations on space, time, and materials. In order for animals to evolve powerful ways to deal with such constraints, they must have ways to represent the situations they face, and they must have processes for manipulating those representations.”

A few years ago I attended a SETI talk by John McCarthy (not long before his death) where he though that evolutionary convergence would apply to models of thought and that therefore humans and aliens could communicate. I personally think he was way out of his area of expertise on that one.

OTOH, Keith Devlin has talked at SETI and suggested that even our fallback of mathematics may not work with aliens.

To throw another issue into the mix, there is the assumption that we all work on roughly the same time frame due to the physical nature of our world and the interactions between organisms being co-evolved. However if plants had thoughts, we wouldn’t know it as it is probably quite slow. Similarly, alien “nerve communication” might be much faster or slower than terrestrial ones. At some point that mismatch would make initiating communication unlikely as the modes are not recognizable to each other. This may really be an issue with machine intelligences, as they may operate on time scales that are not based on biological restraints. We can already see that with our own attempts at AI.

Paul nice article as usual. I found this interesting, “We may, in fact, lack the neural structures to conceptualize and analogize these advanced levels because an alien culture would have developed modes of thought based on its own experience that are too remote from our more limited grid.”

I remember back in college, when we were programming neural nets. I created a visual neural net program that showed visually how it learned a pattern, you could see that after many iterations the program would never come to 100%, it hovered around 99%. This show that a neural net and to some extent the human mind may never be able to fully learn anything.

We understand things by being able to recognize patterns. If the patterns are too complex then the behavior appears to be random. Do civilizations appear more random to an outside observer as they become more complex? Using our current civilization as an example, at the very detailed level, what the members of our society do have fairly simple explanations (eating, sleeping, working, procreating, etc.). Viewing our civilization from street level is much more complex (politics, marketing, altruism, competition, etc.). At 10,000ft we look like an ant colony with pieces of our civilization moving here and there. At 200 miles we look like a fluorescent algae infestation on the planet’s surface.

We are not algae. Aliens may appear like fluorescent algae from a distance but closer inspection would likely reveal that their behavior is not random and can be understood. The question of whether we can get close enough to gain that understanding is another matter.

PS: There is no guarantee that an alien civilization will have more than one member in it. The entire civilization could have collapsed down to the equivalent of one organism where the individual “cells” would not be aware of the overall group consciousness.

“If a lion could speak, we would not be able to understand him.” — Wittgenstein

Roadside Picnic is a great portrayal of truly alien aliens, but I think my favourite for that is Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris.

It reminds me of a quote, I think from an essay Doug Vakoch wrote, but he may have been paraphrasing someone else. Either way, it described scientific development as climbing a mountain. We’ve found our own way up the mountain but other alien civilisations may find an alternative route, or even be climbing a different mountain altogether. I rather liked that analogy.

Thanks for the tip on Wide World Mind and Roadside Picnic…..I’m here for that reason alone….One more thing, though….intelligence and biology, like the evolution of the stars, may develop during similar time lines and may not be so incomprehensible after all….Rosetta Stones may be the missing piece we’ll need….Ask the Singularity…..When it gets here…..Downplaying humanity’s potential may be a risky bet….Example….Wide World Mind and Roadside picnic…..JDS

Alex,

Your comments about the potential disconnect between timeframes required for us to discern a recognizable pattern from their communication or behavior is very interesting. I think scale could also fit into this framework. If one is so close to a human being that all you can see is the behavior of one of our neurons, then this behavior would look fairly simple but would not seem to contain any informational value (randomness). The scope of view would seem to be important for determining meaning.

The question is can we attain the proper scope (time and scale) to recognize the patterns.

This article reminded me of a discussion in a Philosophy of Science Fiction class I took at university. We discussed the very ideas presented in this article.

One of the most interesting discussions revolved around a “metaphoric” language. That is a language that uses metaphors, similes, and allegories to communicate information. These discussions centred on an episode of Star Trek TNG called Darmok in which the crew of the enterprise attempt to communicate with a race that communicates with such a language. Wiki article: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darmok

In this episode the trouble with communicating comes down to a problem of semiotics. The computer has no point of reference on the alien history therefore it can not translate the alien’s symbols into human symbols. How far away is English from a metaphor language? There are a lot of terms and expressions used in everyday speech that are metaphoric and without understanding human history and culture it would be difficult to communicate these ideas. We see this enough between languages on our own planet.

We also discussed the Ender series of books by Orson Scott Card. In these books card presents a “Hierarchy of Foreignness”. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Concepts_in_the_Ender's_Game_series#Hierarchy_of_Foreignness

Card, however, presents cultural misunderstandings in his fiction. The Humans and Buggers did not understand at first because the hive minded Bugger’s and Human’s concepts of murder were completely different. Killing a single bugger was the equivalent of a human loosing a hair, a couple brain cells, ie rather insignificant. Where as we humans value individual lives much more. These different values led to war between the two species.

If I attempt to think about the topic I am left with the notion that if two species are in fact intelligent and do in fact want to communicate with each other they will be ingenious enough to find some sort of common ground through which they can communicate, even if it means creating a history together. Simply: If two species can come to trust each other enough to attempt dialogue then they will succeed.

Paul, you wrote above “…it should definitely be on the short-list for Centauri Dreams readers.” What else is on the Centauri Dreams readers? I see many blogs publishing lists of relevant books, I think it would be great if you did too. A post that listed the five or ten most important books on this blogs topic would be very interesting.

MattJ, I put together an extensive list for my book and have updated it since, but I need to go ahead and put together the comprehensive list for publication here. I’m way behind on this but I’ll try to get to it after the Houston symposium (100 Year Starship). Thanks for the jog!

Tulse writes:

Absolutely! Solaris is stunning, unforgettable. I always find Lem’s work rewarding.

Phil wrote: “If I attempt to think about the topic I am left with the notion that if two species are in fact intelligent and do in fact want to communicate with each other they will be ingenious enough to find some sort of common ground through which they can communicate, even if it means creating a history together. Simply: If two species can come to trust each other enough to attempt dialogue then they will succeed.”

I think this is a good concept. If the alien civilization wants to be to be understood, then they will take steps to accomplish this goal. Understanding their motives and intentions without cooperation from them would be very difficult regardless of their level of development.

By the same token, what if we were to encounter a diverse sample of alien intelligences and find that among all the differences there were some consistent areas of conceptual similarity or modes of thought? That would raise some interesting questions too.

Phil said, “If I attempt to think about the topic I am left with the notion that if two species are in fact intelligent and do in fact want to communicate with each other they will be ingenious enough to find some sort of common ground through which they can communicate, even if it means creating a history together. Simply: If two species can come to trust each other enough to attempt dialogue then they will succeed.”

What happens if it’s just impossible to find common ground? The “alien-ess” is just to big a divide? What if an alien lives for millions of years and takes decades to enunciate a single word? or they live so quickly that generations literally pass before we can say “hello”? I can only imagine what kinds of perspectives an intelligent being such as these would have, and these are the ones I can only imagine, to often the universe throws us things we could never imagine.

That “Roadside Picnic” sounds quite intriguing although I think that it’s only due to have a limited run and also in certain select cities rather than everywhere. From what I read in Discover magazine its description stated that they believed the aliens had come for a, sort of, family picnic if you would. They left behind their rubbish quite different from the usual debris left behind.

I’d just like to throw out one comment concerning the Curiosity mars probe. I have to admit truthfully that I didn’t think it would work; it just seemed too complex and too many things had to occur exactly in sequence to permit it to come together as it should. They said that there was something like 79 different pyros that had to go off in a certain sequence, etc. I guess this just goes to show that provided you’re willing to pay sufficient and intense attention to all the details the final product can be relied upon to work as designed. This is a lesson I think for any type of interstellar voyages: they will be of considerable complexity and they will be completely utterly on their own with no one or anything to be in communication with them, so they have to work right because there’ll be no second chance if there is even a single point of failure of sufficient seriousness.

I find it pretty exciting that Michael Chorost found my original comment interesting enough to analyze my thoughts in his article in Psychology Today. However, I was not arguing that aliens will be so different from us biologically that we can never hope to understand them with the scientific method.

My argument is that an alien society may have developed so differently from ours that we can’t understand them if we retain all our human biases, and that there is probably no absolutely universal definition of sanity. Many popular depictions of the SETI program seem to assume the sort of “kindred intelligence” that wants to help us or at least spread the warm and fuzzy feeling of cosmic community, and I think this clouds our thinking about aliens. People expect aliens that can be easily understood in human terms, but to understand an alien, we have to objectively examine it without trying to apply human thought patterns to its behavior.

Moving on to how we might actually try to understand aliens, I agree with Michael that bizarre alien bodies are likely to be the easiest differences to understand, but I think he underestimates how different an alien society may be. An alien race’s anatomy, means of reproduction and care of young, environment, development of technology, etc. influence what kind of society will result. So while bizarre alien bodies aren’t our biggest barrier to understanding, a different society will result among aliens who have entirely different bodies and live in an entirely different environment.

Here is an example. Humans have a smaller gut than other primates, allowing for extra blood to go to our energy-hungry brain. Because of this, we need to cook our food- we can’t live on a diet of raw food, because our guts just aren’t up to digesting it. Out of this adaptation comes cooking. An nowadays, we have books, TV shows, and web sites devoted to sharing recipes and so on. But what if an alien arrived who had found a different solution to the brain vs. gut problem? This alien would be faced with an entire aspect of society that was ultimately the result of a particular evolutionary development that had never occurred on its home planet. We can expect the same to occur for aliens- a single biological difference could result in a whole aspect of society.

Do I disagree with Michael? Not really, since I think we can study and understand aliens- and their differences from us- should we ever come across them. I never argued that science couldn’t get a grip on alien societies. My question is, can the bulk of humanity deal with an alien society when humans can hardly get along with each other? There could be wonderful things, ancient civilizations, whole different ways of thinking and living out there among the stars, but are we really ready to deal with them?

“Anything that’s strange is no good to the average American. If it doesn’t have Chicago plumbing, it’s nonsense. The thought of that! Oh, God, the thought of that! And then- the war. You heard the congressional speeches before we left. If things work out they hope to establish three atomic research and atom bomb depots on Mars. That means Mars is finished; all the wonderful stuff gone. How would you feel if a Martian vomited stale liquor on the White House Floor?”– “June 2001: And the Moon Be Still as Bright”, The Martian Chronicles, Ray Bradbury

Looks like a fascinating novel, something to be turned into a movie someday.

Though I am a complete layperson with regard to ET, I would argue that any advanced intelligence (meaning: advanced enough to build a technological civilization capable of space travel or at least spae communication) will have a few basic things in common:

– mathematics and problem solving abilities.

– curiosity and the drive to explore.

– some kind of common morality.

In other words, I am comvinced that any such advanced ET would be highly interested in us.

Whether they would also show us a kindness and morality beneficial to us is an entirely different matter.

I think Chorost should be a little more careful:

“Arthur C. Clarke famously said that any sufficiently advanced technology will seem like magic.”

The actual quote from Clarke is:

” Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

That is way different from being ‘like’ magic.

In fact someone refined this to sharpen the idea by saying:

” Any sufficiently advanced technology will be indistinguishable.”

(Can’t remember who it was.)

A theme explored in 2001: A Space Odyssey , at least the 1968 film and novel version … the real core of the film being Clarke’s Childhood’s End. (One might say Kubrick trumped Clarke , because when the sequel 2010 was offered to Kubrick he did not like the change in the Monolith Makers from transcendent beings to Cosmic Lego diddlers…. (tho mainly because Kubrick did no do sequels to his films, what a refreshing idea!)

Ditto on Solaris, I am still astounded that two films were made from this very sophisticated and mostly philosophical novel.

(While the great baroque SF space opera THE STARS MY DESTINATION is still on the sidelines with ‘make me!’ pained in red letters all over it!)

Anyway….. besides Solaris, Childhood’s End , Phol’s Heechee stories, Le Guin’s exquisite Left Hand of Darkness, Blish’s A Case of Conscience , the often forgotten Algis Budrys novel Rogue Moon … and so many more… modern science fiction has explored XT ‘indistinguishability’ in so many ways it’s hard to know where to start.

Of course, the reality will be even stranger.

Decent SF has tried hard to bridge the imagination gap, to understand the truly alien. My favourite depiction of multiple alien species trying to interact, with varying degrees of mutual incomprehension, is C.J.Cherryh’s “Chanur” stories. Of course, what we fail spectacularly at imagining are entities far larger and older than us. The motivations of such vast, semi-immortal species would be very hard to know. Fred Hoyle’s “Black Cloud” was too much a reflection of the scientists communicating with it. A multitude of vast and weird aliens that we can somehow relate to have been depicted – or left off-stage and hinted at by their semi-sentient automation. An unfairly under-rated depiction of beings truly alien and hostile to us, for reasons we barely grasp, is found in Sean Williams & Shane Dix’s “Orphans” trilogy.

I hope the reality will be more benign, but there are no guarantees.

Hi Paul,

I’ve been reading Ian Banks’ Culture novels. I must say that I am fairly widely read in SF but Banks’ conception of a galaxy full of aliens and how they interact is simply–well, it’s thoughtful, different, believable, and at the same time entirely personal.

That’s the thing about Roadside Picnic as a vision of aliens that leaves me a bit wanting. Banks shows us how a universe full of stunningly different critters would interact: a full range of humans separated by thousands of years’ history (kings on the one hand, sublimated individuals on the next planet), plus odd aliens barely intelligible.

I admit that the huge space opera is my favorite genre (Hamilton, for example). But Banks–who I’ve avoid for years because I once picked up a book and saw that there was a king and a princess in it and put it back down– Banks is nearly an entire genre. I can’t recommend this work enough. Thankfully he has nearly a dozen of these very long novels!

What if intelligence follows a fractal pattern and can therefore be understood based upon the scale of the problems that intelligence is able to solve? For example, looking back at the times before massive ocean-going ships. People knew it could be done but just didn’t know how to apply it in practice. Same as the problems we now face with potentially transporting people around the solar system, we know it can be done we’re just not clear on the best way to go about it. Same again as some point in the future, when travel across the solar system is as common as air travel across the globe is today, when we begin contemplating travel between the stars.

Perhaps if the above is applicable then we may be able to begin understanding an alien intelligence and possibly use that as a foundation for establishing communication. Assuming that all intelligent species are faced with, and attempt to solve, the same problems maybe that common ground could be all that is required.

Christopher Phoenix said on August 8, 2012 at 19:45:

“My argument is that an alien society may have developed so differently from ours that we can’t understand them if we retain all our human biases, and that there is probably no absolutely universal definition of sanity. Many popular depictions of the SETI program seem to assume the sort of “kindred intelligence” that wants to help us or at least spread the warm and fuzzy feeling of cosmic community, and I think this clouds our thinking about aliens. People expect aliens that can be easily understood in human terms, but to understand an alien, we have to objectively examine it without trying to apply human thought patterns to its behavior.”

SETI’s limitations, which its pioneers recognized early on, mean that until we can start ramping up a serious set of programs to look in multiple places and way, we are pretty much stuck with hoping that we can find intelligences not too different from our own. The beings that float among a Jovian style world’s clouds or swim in deep alien waters will have to wait, unless they’ve also got a radio beacon program going.

On the plus side, the fact that we have to search for ETI familiar to us could mean that communication may be more likely. And it would not be very surprising if ETI conducting their own SETI have set parameters similar to their own species, also out of necessity if not a bias such as only their kind could possibly be intelligent and worth talking to.

Roadside Picnic is available in English online here:

http://lib.ru/STRUGACKIE/engl_picnic.txt

Michael Spencer writes:

I discovered Banks thanks to readers like you who had recommended him, and have now read about half his Culture novels. The man is a superb and thoughtful writer, and the interactions you describe are believable indeed. But I think the Strugatskys’ scenario is just as likely, a universe where the degrees of separation between alien species are almost too vast to bridge.

Greg said, “What happens if it’s just impossible to find common ground? The “alien-ess” is just to big a divide? What if an alien lives for millions of years and takes decades to enunciate a single word? or they live so quickly that generations literally pass before we can say “hello”? I can only imagine what kinds of perspectives an intelligent being such as these would have, and these are the ones I can only imagine, to often the universe throws us things we could never imagine.”

See that is the thing, would either of these species even recognize that the other is intelligent. If they do not even notice each other then of coarse they have no hope of ever communicating, however, if they do notice each other, and they are intelligent, and WANT to communicate then they would figure it out.

I was thinking about this some more after I made my post above. I was trying to figure out what Aliens and Humans would have in common. I came to a conclusion which I would be interested in hearing others thoughts on.

GAME THEORY.

Aliens and Humans should have concepts of game theory. That is they should be able to put themselves in our shoes and ask, “What would I do if I was in that situation?” Or, “what action will bring the most good to this creature?” This ability is one of the corner stones of intelligence. When we test animals for intelligence this is one of the things that is tested, can the animal imagine itself in the position of another animal, or its future self?

Personally, I can not imagine an intelligent being (besides perhaps a Boltzmann Brain) that would not have a concept of game theory. Perhaps it is not formalized as we humans have attempted to do, but they must have at least an intuitive sense of its existence. I do not have strong arguments for this, but I just can not imagine an intelligent being evolving without this ability.

Therefore, perhaps the best way to communicate with an alien would be to play a game with it. Once the game is complete both parties would have some common ground around which a dialogue could be created.

A. A. Jackson said on August 9, 2012 at 6:08:

“A theme explored in 2001: A Space Odyssey , at least the 1968 film and novel version … the real core of the film being Clarke’s Childhood’s End. (One might say Kubrick trumped Clarke , because when the sequel 2010 was offered to Kubrick he did not like the change in the Monolith Makers from transcendent beings to Cosmic Lego diddlers…. (tho mainly because Kubrick did no do sequels to his films, what a refreshing idea!)”

LJK replies:

I also did not like how Dave Bowman went from being the literal next step in human evolution (in the 2001 novel, the evolved Dave had the ability to divert and detonate several nuclear missiles fired at him from his perch in Earth orbit) to a cosmic messenger boy in 2010.

Perhaps that was just one of his duties as Human 2.0, but the sequel seems to say that after his staring at Earth at the end of 2001 as a giant fetus and pondering what to do next, he just floated around in space until the Soviet spacecraft Leonov showed up at Jupiter.

Kubrick knew he could not top or equal 2001: A Space Odyssey, nor has anyone else in the last 40-plus years. This does not mean there hasn’t been some good SF before and after 2001 (especially in the decade or so before Star Wars came along and lobotomized the genre), but I am still waiting for its like.

A. A. Jackson then said:

“Ditto on Solaris, I am still astounded that two films were made from this very sophisticated and mostly philosophical novel.”

LJK replies:

Lem did not care for either film version of Solaris. In fact I believe he refused to watch the second one as he felt they tried to turn it into a cosmic soap opera, missing the main point of the novel.

I thought the first one was closer to the feel and ideas of the Lem novel, but Andrey Tarkovskiy veered off in his own direction towards the end. Apparently he also put in a very boring beginning to chase away the Soviet censors, so he could then do the rest of the film the way he wanted. I understand and appreciate that artists have the right to express and interpret via art in their own ways, but I am still waiting for the definitive Solaris film. Or perhaps it will always remain better in novel form.

But yes, if you want not only great science fiction as literature and aliens that are truly alien, where humans are not the focus of their whole existence or even of much interest to them (just like the literal Universe), then Lem is your author. I also recommend his 1968 novel His Masters Voice. It makes most other SF, especially written by Westerner, look like kids stuff.

Frank Belknap Long, Jr. , in his short story, The Last Man, wrote an unhappy tale about an accident of Nature; grasshoppers suddenly evolved into six foot long flying big brained creatures who tried their damndest to make pets of individuals among the surviving race of men. It didn’t work. The last man continued to rebel against being anybody’s pet. He finally dies by his own hand rather than live in a gilded cage….Hollywood could have just changed the ending and had another Planet of the Apes on its hands….JDS

Phil said, ” if they do notice each other, and they are intelligent, and WANT to communicate then they would figure it out.”

Okay if you take my example of a life form that lived for millions of years and took a decade to say one word, and lets say we were mutually aware of each other as intelligent beings. We could find away to communicate certainly, over centuries! To us whatever we could learn would be moot since waiting for centuries to discuss an idea would loose it’s meaning to us.

You’ve mentioned Game Theory; here is Wikipedia’s article on Drama Theory, a variation which involves emotional and possibly irrational responses, leading players to redefine the game.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drama_theory

Google gives plenty of other results for the phrase.

@LJK

Agreed on the Tarkovskiy version of Solaris , tho quite thin, the Steven Soderbergh 2002 version does treat the novel with respect, and is one of the those rare US science fiction films that , at least, trys for serious science fiction.

Yet Lem’s novel is unique , in it’s way , in exploring the anthropomorphic limitations of limitations of communication with an alien intelligence. Lem spends a lot of time on this philosophy, of profit to anyone interested in SETI, actually sobering for our human confined box.

Yet, this is a prose entity, and , I don’t think, lends itself to a visual narrative, a great novel but that’s all.

Lem was quite a curmudgeon , he wrote fine novels , other works, yet seemed oddly latched to bad impressions of lessor modern SF.

I know, once when in Poznan, working with a scientific collaborator, who was an SF fan, he showed me how much Phil Dick was in the local bookstore.

And he knew Lem was a fan of Dick. Yet my friend could not puzzle out if Lem had ever read Sturgeon or even if a copy of Left Hand of Darkness ever came his way.

My Polish , science fiction reading friend, thought Lem had a blind spot for top modern science fiction.

Ronald writes: “Looks like a fascinating novel, something to be turned into a movie someday.”

The idea was loosely adapted into Stalker, by Andrei Tarkovsky, the same director who did the first adaptation of Solaris. It doesn’t follow the book closely at all, but uses the central conceit of the inexplicable alien artifacts with bizarre powers and zones prohibited by the government, and “stalkers” who illegally enter the zones to scavenge for those artifacts, or guide others through the zone. The film is more of a psychological study, and uses no special effects to speak of, but I find it unforgettable.

If we’re talking about inexplicable aliens and space opera, I’ll put a plug in for Alastair Reynolds’ Revelation Space novels. In some cases, the aliens in his universe are so “other” that despite their power it isn’t even clear if they are sentient (such as the Pattern Jugglers and Inhibitors). Another interesting feature of his novels is that biotechnology has been used among various groups of humans to effectively make them alien to each other (such as the hive-mind-based Conjoiners).

Ronald:

I must say I agree with this. It is hard to know anything, of course, having zero data on other intelligences. However, I tend to be with those who think that intelligence, like eyes and limbs and wings, is just a tool developed throughout evolution for a particular purpose. As eyes are for seeing, limbs for walking, and wings for flying, intelligence is there for navigating the world.

Just as we are likely to recognize eyes and limbs and wings on alien animals, we are likely to be quite able to understand extraterrestrial thinking, if there is any out there.

Of course, admittedly, this is a boring belief. It is much more fashionable, and a noble challenge in SF, to outdo one another in imagining how much different aliens will be from us. And then go further and claim that aliens will be even much more different than we could ever imagine. To me, this is the kind of flight of fancy that regularly develops wherever there is a profound lack of data. It is not to be taken seriously, except as an interesting diversion.

So maybe The Twilight Zone episode “People Are Alike All Over” is more on target than we might imagine – just change the location from Mars to Alpha Centauri.

http://twilightzonevortex.blogspot.com/2012/03/people-are-alike-all-over.html

This famous quote from Solaris might explain in yet another sense why SETI (and METI and CETI and interstellar colonization) has yet to work (more comments after the quote):

“We take off into the cosmos, ready for anything: For solitude, for hardship, for exhaustion, death. Modesty forbids us to say so, but there are times when we think pretty well of ourselves. And yet, if we examine it more closely, our enthusiasm turns out to be all sham.

“We don’t want to conquer the cosmos, we simply want to extend the boundaries of Earth to the frontiers of the cosmos. For us, such and such a planet is as arid as the Sahara, another as frozen as the North Pole, yet another as lush as the Amazon basin.

“We are humanitarian and chivalrous; we don’t want to enslave other races, we simply want to bequeath them our values and take over their heritage in exchange. We think of ourselves as the Knights of the Holy Contact. This is another lie. We are only seeking Man.

“We have no need of other worlds. We need mirrors. We don’t know what to do with other worlds. A single world, our own, suffices us; but we can’t accept it for what it is. We are searching for an ideal image of our own world: we go in quest of a planet, of a civilization superior to our own but developed on the basis of a prototype of our primeval past.

“At the same time, there is something inside us which we don’t like to face up to, from which we try to protect ourselves, but which nevertheless remains, since we don’t leave Earth in a state of primal innocence. We arrive here as we are in reality, and when the page is turned and that reality is revealed to us — that part of our reality which we would prefer to pass over in silence — then we don’t like it any more.”

http://www.remq.edu.ec/libros/Stanislaw%20Lem%20-%20Solaris.pdf

Maybe there are really advanced (or really different – or both) ETI which do things in places so far out of our ken that it doesn’t matter if we ever encounter each other or not. Or maybe other ETI make Starship Troopers to be another more accurate rendition of what is out there and what will happen if we meet up in our current or near-current state.

There may be alien beings similar to humans, but they will never be THAT similar ala Star Trek. And if that similarity includes expanding versions of themselves and their home worlds….

“The Twilight Zone” (1960s version) had two Alien contact episodes that acted as bookends to the series. The first episode “The Galaxy Being” is about the attempts (and failures) to communicate with a very alien yet sympathetic creature.

The last episode of the series “The Probe” is about an automated probe that accidentally picks up survivors from a plane wreck. The characters have to figure out a way of communicating with the probe (or the creatures that sent it) before it takes off. They also have to tell it that the probe itself has been contaminated with a dangerous creature.

Both episodes are notable for their believable attempts at communicating with aliens (by 60s standards).

FrankH writes:

I haven’t seen ‘The Probe,’ but ‘The Galaxy Being’ was actually on The Outer Limits, so I think that’s the series you mean. I’ll check, as I have the show on DVD.

Could it be that we wouldnt recognize our own evolutionary development until we have moved on to the next phase? The process hidden by proximity? Sometimes you cant see the tree because you are looking to closely at the leaves

I would imagine that it would simply depend on which alien species we encounter. All possibilities being possible. One possibility being that we are actually the most advanced species and its up to us to bridge tthe gap to the others. Or maybe the reason we havent had any contact is because “they” are waiting for us to reach the correct level of evolution. Our society could be of great interest already. Especially if the technology was “indistinguishable ” . Size of the alien could be a factor. A n alien of sufficient size could look like a galaxy to us. Transformers? Aliens. Mcouldbe mechanical and highly indistinguishable from trees. For that matter we have aliens that have evolved right next to us that we cant commu

I’m really having a lot of fun with these discussions and the comments spinning off of them. I’m grateful to Paul Gilster and to everyone who is taking time to read and share their thoughts.

I read Roadside Picnic last week and posted my thoughts on it here (http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/world-wide-mind/201208/the-uncanny-valley-alien-technology). As terrific as it was, I thought there were better novels that explore the weirdness of alien technology, and I discuss two, Macroscope and His Master’s Voice (and, as LJK says, HMV makes most other SF look like kid stuff.)

Christopher Phoenix: You’re right, we aren’t really disagreeing with each other. In a way, the subject matter is too big and amorphous for people to really disagree. It’s like people arguing over where to go in a cavern when there’s no lights to show the shape of the place. I was really just using your intriguing comment as a departure point for thoughts going off in a different direction.

A.A. Jackson: Point taken – I should have quoted Clarke accurately. I’ve revised the entry.

Michael Spencer, Ian Banks sounds fascinating and I will try one of his novels.

Phil, I was intrigued by your comment about game theory. This is not something I know a lot about, though in his book THE BETTER ANGELS OF OUR NATURE Steven Pinker suggests that when one models human interactions with game theory, reductions in violence and increases in moral standards fall naturally out of the analysis. That aside, I’d say that if two alien civilizations _want_ to communicate, they will find a way even if they are very different.

As an aid to anticipate what aliens might be like, why not first attempt investigate what we are really like?

I will start the ball rolling by taking aim at what has already been pointed out as our most likely distortion. We tend to view outgroups as more similar to each other than they really are, so why not examine the possibility that it is us who are closer to the hive mind type among sentient species.

I notice in politics if a popular theme ever gains currency, most start to think it true, no matter how false. Our greatest problem here is that everything in the political world is very complex and yet we fool ourselves it is simple. And that makes this a particularly fruitful ground to study the real nature of our own minds. Sure, most of us desire simple explanations to comfort us – but why do we all cling onto the same catchphrases. I suspect that if this matter were put to objective study, its uptake would turn out to correlate to the repetition, and be irrespective of the logic from unbiased evidence.

I think the reason that the hive nature of sane humanity has gone unnoticed is that war *feels* so similar to individual aggression, yet it is marked by its high levels of cooperation and willingness to die for other members of the ingroup. Even accounts where someone leaps on top of a live grenade to save his *brothers in arms* do not seem that uncommon in the heat of battle – nor does that battle have appear as a fight against other humans, but could equally be against a battle ship.

Also the puzzle springs to mind as to why the ratio of killings in war to murders always seems so high in male humans. Why are the mentally well so reluctant to kill given circumstances of personal gain, and so keen to for reasons of group gain.

More typical ETI’s might be horrified by all this collectivism, and have developed under an ultra capitalist type system whereupon externalities become akin to a sacred duty in addressing. Perhaps then they will be most horrified by the small proportion of time that our governing bodies address such causes.

To us most ETI’s would then seem obsessed by identifying internal threats, the governments would only seem interested in the very long term, and their individuals would be outrageously dangerous to meet.

Ken Wilber’s ideas of “evolutionary development” or as commenter david here “evolutionary level” is of course first of all a tautology but more importantly the old failed paradigm of “ladder of descent”. That was a hold over from philosophy and religion, and has failed in test against evolution*s behavior. Evolution has no specific directions, no guarantee of development of traits.

In fact, over half the extant species are parasites in one way or other, and parasites are most often simplified from earlier body plans (albeit they can have complex life cycles). Hence there is more “evolutionary simplification” than “evolutionary complexification”. The early complexification is understood on a basis of a simple first universal common ancestor. (The UCA period was ~ 40 % of genome family evolution according to modern genome research, see Goldman et al.)

In general it is noted that if evolution would be restarted, it would not show the same pathway due to contingency. The question of frequency of evolution of complex multicellular is an open question in astrobiology. The same goes for spoken linguistic capability. As the elephant trunk, the trait has only evolved once so far. Elephant and human analogs may be very rare.

This is the most likely prediction right now, if you ask biologists at the same time they confess they do not really know as of yet but that is what the theory predicts. In other words, it is too unconstrained a question to think of consequences of “contact”. We can’t predict what that would be.

Torbjörn Larsson:

This is an interesting idea. What, really, is an elephant trunk? If you define it generally as a prehensile appendage, it has evolved numerous times. Human arms and squid tentacles spring to mind. It only becomes unique when you isolate it with enough qualifications, such as “prehensile appendage also used as a breathing tube, containing no bone”. By adding enough qualifications, you can easily make anything unique.

It is not much different with “spoken linguistic capability”. Is whale song included? bird song? Apparently not, but is the distinction sufficiently fundamental? Can we even express the distinction coherently?

That said, I agree with you on language/intelligence. I would consider it in fact, unique. But I would not take that as an indication of rarity, but rather of disruptiveness. Anything sufficiently disruptive trait evolves only once, because it eliminates its own origin. There is no chance a second species could evolve language or intelligence while we are around to keep it from happening.

Torbjörn Larsson:

In astrobiology, perhaps, but not in regular biology. It is well known that multicellularity evolved independently many times. For example, here:

Bonner, John Tyler (1998). “The Origins of Multicellularity”. Integrative Biology: Issues, News, and Reviews 1 (1): 27–36.

http://courses.cit.cornell.edu/biog1101/outlines/Bonner%20-Origin%20of%20Multicellularity.pdf

I see Stanislaw Lem has been mentioned a fair bit in the comments, although I don’t think anyone has mentioned his analysis of _Roadside Picnic_, which is the final chapter of _Microworlds_ (1984).

Personally, I’ve never read _Roadside Picnic_, only Lem’s analysis. Lem thinks the events of the novel are best explained as follows (I condense as much as is possible):

“A spaceship filled with containers that held samples of the products of a highly developed civilisation came into the vicinity of the earth. It was not a manned ship, but an automatically piloted space probe. […] In the approach to earth, the vessel sustained damage and broke into six parts, which one after another plunged from their orbit to earth. […] The senders, unable to be absolutely certain that no catastrophe would befall their spaceship during its landing, must at least have provided for a minimising of the consequences, and have done so precisely by installing on board a safety device that would not allow the effects of the catastrophe to spread.“