It was back in 2010 that Nir Goldman (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory) first predicted that the impact of a comet on the early Earth could produce potential life-building compounds like amino acids. Goldman was using computer simulations to make the call, studying molecular dynamics under the conditions of such impacts. He found that the shock of impact itself should produce amino acids and other prebiotic compounds, regardless of conditions on the planet. It was intriguing work because it suggested that impacts in the outer system (think Enceladus, for example) could produce enough energy to create the shock synthesis of prebiotics there.

Now Goldman, working with collaborators from Imperial College London and the University of Kent, has gone beyond the simulations to test the process in the laboratory. By firing a projectile into a mixture comparable to the material found on a comet — water, ammonia, methanol and carbon dioxide — the team was able to produce several different kinds of amino acids including D- and L-alanine and the non-protein amino acids α-aminoisobutyric acid and isovaline as well as their precursors. The high-speed gun, located at the University of Kent, propels steel projectiles at 7.15 kilometers per second into the target mixture. Says Goldman:

“These results confirm our earlier predictions of impact synthesis of prebiotic material, where the impact itself can yield life-building compounds. Our work provides a realistic additional synthetic production pathway for the components of proteins in our Solar System, expanding the inventory of locations where life could potentially originate.”

Planetary impacts from comets were surely widespread in the early Solar System, and we now know that they could produce prebiotic molecules and thus play a role in the development of life. What Goldman’s team has demonstrated is that the shock of impact itself is enough to produce the energy needed for the synthesis of complex organic compounds from the comet’s ices. It is possible that this process began life’s course on Earth during the Late Heavy Bombardment, the era between 4.1 and 3.8 billion years ago when collisions were rife in the inner system.

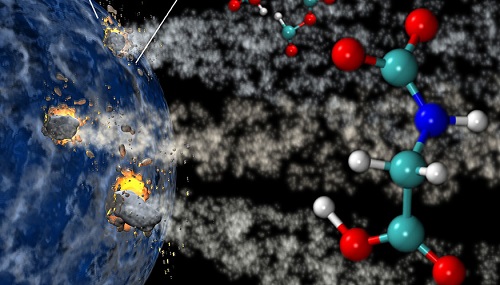

Image: Comets contain compounds such as water, ammonia, methanol and carbon dioxide that could have supplied the raw materials that, upon impact with the early Earth, would have yielded an abundant supply of energy to produce amino acids and jump-start life. Credit: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

The same building blocks can be produced by the impact of a rocky meteorite into an object with an icy surface, making the icy moons of outer gas giants an interesting environment for astrobiology. Mark Price (Imperial College London) notes how much still needs to be understood:

“This process demonstrates a very simple mechanism whereby we can go from a mix of simple molecules, such as water and carbon-dioxide ice, to a more complicated molecule, such as an amino acid. This is the first step towards life. The next step is to work out how to go from an amino acid to even more complex molecules such as proteins.”

For more, see this Imperial College news release and this release from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The paper is Martins et al., “Shock synthesis of amino acids from impacting cometary and icy planet surface analogues,” published online in Nature Geoscience 15 September 2013 (abstract).

2 points:

1. Amino acids have been found in space before, starting with meteorites (most notably the Murcheson) and extending to cometary surfaces, dust grains etc.

2. Getting to proteins is much harder as they require conditions that remove water when the peptide bonds form.

We seem to be going back to the early excitement of the 1950’s Urey/Miller experiment where abiotic synthesis of amino acids was seen as the basis for the origin of life. But life is composed of more than proteins, in particular RNA and, probably later, DNA. If cometary impact is yet another mechanism for AA synthesis, we are not really any further forward, as AAs are ubiquitous in space. More compelling would be mechanisms of AA synthesis with strong chiral bias, and RNA synthesis.

We may never know the origin of life on Earth, but we could get some good clues if we could find and analyze life elsewhere, particularly from other star systems. While I don’t expect that even a probe traveling at c will be of much help here because of the distances involved, if we chanced upon meteors that were demonstrably from another system and contained dormant/dead microbial life, that could shed light on a number of key questions about life.

This is excellent news and makes me more optimistic than ever that we will see biosignatures in exoplanet atmospheres sometime in the next 10 years.

Interesting that nonprotein AAs were formed as well. Maybe different AAs are components of proteins in other biospheres than the ones for Earth.

Thats interesting, Mr. Tolley, isn’t it? Whilst there are several proposed mechanisms for producing a L-chiralty bias, they all fail to explain the scope of our observations in space. A observation which extends far beyond our solar system.

What could be responsible for producing a L-chiralty bias on such a vast scale?

As Alex says, this whole issue has been very well covered in the 50’s with the Urey/Miller experiments, which do not require space or high velocities and presumably produced much more of the stuff, including nucleic acids. No reason here to look to space, except for the purpose of drawing attention.

Besides, the focus on amino-acids is puzzling. If they had found nucleic acids, that would have been more impressive. Life did not start with amino acids. They are not suitable for self-replication. The core of biological self-replication is nucleic acids, particularly RNA. As far as I remember, the Urey/Miller experiments produced all or most of the common nucleic acids.

The argument is pretty simple: DNA can replicate, but cannot form complex shapes. Proteins form complex shapes, but not replicate. RNA can do both. Both are needed for life, so RNA must have been first. DNA and proteins are subsequent adaptations.

Besides the above logical conjecture, there is also plenty of real evidence for this in the makeup of ribosomes and transcription complexes, which rely heavily on RNA components that are considered vestiges left over from all-RNA times.

Thermodynamics of origin of life: Why is there life?

(Why does life originate and exist now? It is the main question! How does life originate? It is the second question!)

The transition between the animate and inanimate matter is a slow. It was predestined by the action of “thermodynamic principle of the substance stability” ( http://www.mdpi.org/ijms/papers/i7030098.pdf ) which describes the forward and backward linkages at the transmission of information between structural hierarchies during the chemical and biological evolution. http://gladyshevevolution.wordpress.com/article/thermodynamic-theory-of-evolution-of-169m15f5ytneq-3/

http://gladyshevevolution.wordpress.com/

See: Thermodynamics and the emergence of life.

The phenomena of life can be explained on the basis of quasi-equilibrium hierarchical thermodynamics of dynamic systems which stands at the solid foundation of thermodynamics of JW Gibbs. Theory can be constructed without using the concept of dissipative structures of I. Prigogine and his ideas about negentropy.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CYr1G5TZO50 http://gladyshevevolution.wordpress.com/article/science-evolution-and-reality-169m15f5ytneq-12/

http://endeav.net/news/22-life-evolution-thermodynamics.htm

From the point of view of thermodynamics, the phenomenon of life is defined as: “Life is the process of existence of constantly renewed polyhierarchical structures during cycles of transformation of labile chemical substances in the presence of liquid water on the planet.”

Hierarchical thermodynamics establishes a common genetic code of life in the universe

Sincerely,

Georgi Gladyshev

Professor of Physical Chemistry

P.S. Biodiversity See: Thermodynamic mechanisms of formation and evolution of living systems On the sculpting living organisms and systems

Fomalhaut’s Stellar Sister’s Comets: Exoplanet Goldmine?

DEC 18, 2013 01:23 PM ET // BY IAN O’NEILL

Astronomers scoping-out the vicinity of the famous star Fomalhaut have discovered that its mysterious stellar sister is also sporting a rather attractive ring of comets.

This news is brought to you by the recently-defunct Herschel space observatory, a European-led infrared mission, that was especially fond of probing the infrared signals being emitted by cool nebulae, the gas in distant galaxies and, in this case, vast icy debris fields surrounding young stars. Sadly, the orbiting telescope was lost earlier this year as it ran out cryogenic coolant, but its legacy lives on.

Located 25 light-years away in the constellation Piscis Austrinus, Fomalhaut A is one of the brightest stars in Southern Hemisphere skies. The bright blue giant is notable in that it hosts a gigantic ring of cometary debris and dust. Embedded within this ring is the infamous Fomalhaut Ab, a massive exoplanet that has been the cause of much debate.

But this new research, published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, doesn’t focus on the stellar “Eye of Sauron,” it is actually centered around Fomalhaut’s less famous sibling, Fomalhaut C.

Fomalhaut C is a red dwarf star and was only confirmed to be gravitationally bound Fomalhaut A and Fomalhaut B in October. Fomalhaut is therefore a triple, or trinary, star system. The small red dwarf star may be the proverbial runt of the Fomalhaut stellar litter, but it appears to share some common ground with its larger sibling.

Full article here:

http://news.discovery.com/space/alien-life-exoplanets/fomalhauts-stellar-sisters-comets-exoplanet-goldmine-131218.htm

http://astrobiology.com/2014/01/the-atmospheres-of-earth-like-planets-after-giant-impact-events.html

The Atmospheres of Earth-like Planets after Giant Impact Events

Source: astro-ph.EP Posted January 8, 2014 10:55 PM 0 Comments

Impact event

It is now understood that the accretion of terrestrial planets naturally involves giant collisions, the moon-forming impact being a well known example.

In the aftermath of such collisions the surface of the surviving planet is very hot and potentially detectable. Here we explore the atmospheric chemistry, photochemistry, and spectral signatures of post-giant-impact terrestrial planets enveloped by thick atmospheres consisting predominantly of CO2, and H2O.

The atmospheric chemistry and structure are computed self-consistently for atmospheres in equilibrium with hot surfaces with composition reflecting either the bulk silicate Earth (which includes the crust, mantle, atmosphere and oceans) or Earth’s continental crust. We account for all major molecular and atomic opacity sources including collision-induced absorption. We find that these atmospheres are dominated by H2O and CO2, while the formation of CH4, and NH3 is quenched due to short dynamical timescales.

Other important constituents are HF, HCl, NaCl, and SO2. These are apparent in the emerging spectra, and can be indicative that an impact has occurred. The use of comprehensive opacities results in spectra that are a factor of 2 lower in surface brightness in the spectral windows than predicted by previous models. The estimated luminosities show that the hottest post-giant-impact planets will be detectable with near-infrared coronagraphs on the planned 30m-class telescopes.

The 1-4um region will be most favorable for such detections, offering bright features and better contrast between the planet and a potential debris disk. We derive cooling timescales on the order of 10^5-10^6 Myrs, based on the modeled effective temperatures. This leads to the possibility of discovering tens of such planets in future surveys.

R. E. Lupu, Kevin Zahnle, Mark S. Marley, Laura Schaefer, Bruce Fegley, Caroline Morley, Kerri Cahoy, Richard Freedman, Jonathan J. Fortney (Submitted on 7 Jan 2014)

Comments: 51 pages, 16 figures, preprint format; ApJ submitted

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:1401.1499 [astro-ph.EP] (or arXiv:1401.1499v1 [astro-ph.EP] for this version)

Submission history From: Roxana Lupu [v1] Tue, 7 Jan 2014 04:04:19 GMT (4788kb,D)