I’ve always found the final factor in the Drake Equation to be the most telling. Trying to get a rough idea of how many other civilizations there might be in the galaxy, Drake looked at factors ranging from the rate of star formation to the fraction of planets suitable for life on which life actually appears. Some of these items, like the fraction of stars with planets, are being clarified almost by the day with continuing work. But the big one at the end — the lifetime of a technological civilization — remains a mystery.

By ‘technological,’ Drake was referring to those civilizations that were capable of producing detectable signals; i.e., releasing electromagnetic radiation into space. And when we have but one civilization to work with as example, we’re hard pressed to know what this factor is. This is where Adam Frank (University of Rochester) and Woodruff Sullivan (University of Washington, Seattle) come into the picture. In a new paper in Astrobiology, the researchers argue that there are other ways of addressing the ‘lifetime’ question.

Image credit: http://www.ForestWander.com [CC BY-SA 3.0 us], via Wikimedia Commons.

What Came Before Us

The idea is to calculate how unlikely our advanced civilization would be if none has ever arisen before us. In other words, Frank and Sullivan want to put a lower limit on the probability that technological species have, at any time in the past, evolved elsewhere than on Earth. Here’s how their paper describes this quest:

Standard astrobiological discussions of intelligent life focus on how many technological species currently exist with which we might communicate (Vakoch and Dowd, 2015). But rather than asking whether we are now alone, we ask whether we are the only technological species that has ever arisen. Such an approach allows us to set limits on what might be called the ”cosmic archaeological question”: How often in the history of the Universe has evolution ever led to a technological species, whether short- or long-lived? As we shall show, providing constraints on an answer to this question has profound philosophical and practical implications.

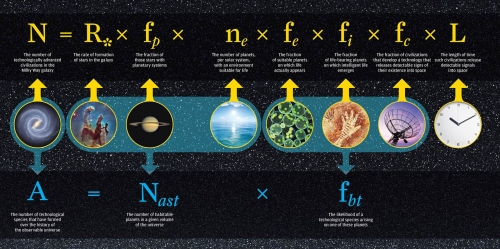

To do this, the authors produce their own equation drawing on Drake’s. Consider A the number of technological civilizations that have formed over the history of the observable universe. Rather than dealing with Drake’s factor L — the lifetime of a technological civilization — Frank and Sullivan propose what they call an ‘archaeological form’ of Drake’s equation. The need for the L factor disappears. The new equation appears in this form:

A = Nast * fbt

Where A = The number of technological species that have evolved at any time in the universe’s past

Nast = The number of habitable planets in a given volume of the universe

fbt = The likelihood of a technological species arising on one of these planets.

You can see that what Frank and Sullivan rely on are recent advances in the detection and characterization of exoplanets. We’re learning a great deal more about how common planets are and how many are likely to orbit in the habitable zone around their star, where liquid water could exist. Their term Nast relies on this work and draws together various terms from the original Drake equation including the total number of stars, the fraction of those stars that form planets, and the average number of planets in the habitable zone of their stars.

From the paper:

With our approach we have, for the first time, provided a quantitative and empirically constrained limit on what it means to be pessimistic about the likelihood of another technological species ever having arisen in the history of the Universe. We have done so by segregating newly measured astrophysical factors from the fully unconstrained biotechnical ones, and by shifting the focus toward a question of ”cosmic archaeology” and away from technological species lifetimes. Our constraint addresses an issue that is of particular scientific and philosophical consequence: the question ”Have they ever existed?” rather than the usual narrower concern of the Drake equation, ”Do they exist now?”

The paper is short and interesting; I commend it to you. The result it produces is that human civilization can be considered unique in the cosmos only if the odds of a civilization developing are less than one part in 10 to the 22nd power. Frank and Sullivan call this the ‘pessimism’ line. If the probability of a technological civilization developing is greater than this standard, then we can assume civilizations have formed before us at some time in the universe’s history.

And yes, this is a tiny number — one in ten billion trillion. Frank says in this University of Rochester news release that he believes it implies technology-producing species have evolved before us. Even if the chances of civilization arising were one in a trillion, there would be about ten billion civilizations in the observable universe since the first one arose. As for our own galaxy, another civilization is likely to have appeared at some point in its history if the odds against it evolving on any one habitable planet are better than one in 60 billion.

We fall back on cosmic archaeology in suggesting that given the size and age of the universe, Drake’s factor L may still play havoc with our chances of ever contacting another civilization. Sullivan puts it this way:

“The universe is more than 13 billion years old. That means that even if there have been a thousand civilizations in our own galaxy, if they live only as long as we have been around—roughly ten thousand years—then all of them are likely already extinct. And others won’t evolve until we are long gone. For us to have much chance of success in finding another “contemporary” active technological civilization, on average they must last much longer than our present lifetime.”

We can play with this a bit. Taking the Milky Way and choosing a probability of 3 X 10-9, we are likely to be one of hundreds of civilizations that have arisen. But drop that probability to 10-18 (one in a billion billion) and we are likely the first advanced civilization in the galaxy. Yet even with the latter constraint, that would still mean we are one of thousands of civilizations that have developed at some time in the visible universe.

I always appreciate work that frames an issue in a new perspective, which is what Frank and Sullivan’s paper does. We can’t know whether there are other civilizations currently active in our galaxy, but it appears that the odds favor their having arisen at some time in the past. In fact, these numbers show us that we are almost certainly not the first technological civilization to have emerged. Is the galaxy filled with the ruins of civilizations that were unable to survive, or is it a place where some cultures have mastered the art of keeping themselves alive?

The paper is Frank and Sullivan, “A New Empirical Constraint on the Prevalence

of Technological Species in the Universe,” Astrobiology Vol. 16, No. 5 (2016). Preprint available.

N is the “number of technologically advanced civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy (such as our own)”.

However, with the final variable Fc, “the fraction of civilizations that develop a technology that releases detectable signs of their existence into space”, that final clause selects us out doesn’t it?

In other words, we are among the myriad civilizations N that do not release detectable signs of their existence into space. Seems to be a disconnect there.

Problems I have with this approach:

1. The universe may be 13bn years old, but that doesn’t mean civilizations can develop at the start of the universe.

First we only have populations of stars without metals. That population has to create the higher mass elements widely enough to create star popuklations dominated with planets formed with metals.

Then we have the issue of how long it takes to create a civilization. On Earth about 4.5bn years.

To me that suggests that there will be a long period from the birth of our universe before any civilizations appear.

Outside the scope of the paper, there is then the issue of archaeological detection. Human structures are barely 12,000 years old, although there are hints on ones 100,000 years old. While new techniques are unearthing new sites, the remains are sparse. After a million years they will be gone.

If dinosaurs had built a technological civilization, there would be no traces left, as far as our detection techniques can manage.

Which creates a problem for falsifying the paper. It may be broadly correct, but even if we had human, FTL star flight, would we find evidence of civilizations on other worlds from the deep past? I think we might only do so where structures or artifacts have been left on worlds like our Moon; geologically inactive and airless, allowing preservation.

The only other artifact that might survive on a living world for long periods might be biological, evidence of non-evolutionary tinkering with life encoded in the DNA.

Now intriguingly recent research has shown that new genes (not from existing genes in the organism or even horizontal transfer other organisms) appear more frequently than expected, with peaks at major turning points in evolution, e.g. Cambrian. While I adssume a natural solution, it is just possible that this could be artificial. We are on the brink of rapid development of genetic manipulation technologies, organisms of which might just survive after humans have disappeared, leaving a living record of our passing that might survive for millions of years.

Might our star probes detect the presence of past civilizations from such life signs?

Hi Alex,

I vaguely remember hearing about the incidence of new genes appearing on the scene more frequently than expected, do you happen to know what source/paper that comes from?

I don’t have a paper, but this article might get you started.

How New Genes Arise From Scratch

All of this assumes that all aliens species would live, evolve at the same rate.

What about species arising in low energy environments. Where a full life cycle of single celled organisms lasts 10 years. That is from fission to fission event. Additionally on such a world multi-celled animals have a lifespan of 1,000 years, and Higher order sentient beings live 5,000 years.

It is a mistake to assume all life forms will have the same

biological metabolic rate. There could be surprises out there.

As I’ve stated previously, there maybe/have been many budding

proto-sentient life forms. And just an equal number of natural upsets waiting to make them extinct in the span of millions of years.

Against 10^-11 for this galaxy, we’re good to go. Let the good times roll. We’ll find them in short order.

Biology seems to be getting much closer to testable theories regarding the evolution of complex life.

For example, the most recent book by Nick Lane, “The Vital Question”, (2015) W.W. Norton & Co., N.Y, N.Y, (ISBN 978-0-393-08881-6), is pretty upbeat about those chances, at least in 2nd or later stellar generations with significant metellicity.

Fascinating speculations, but with many suggestions regarding experiments now in progress or ‘doable’ in the near future.

I am afraid this is only Nick Lane being upbeat. The rest of the field has no such optimism. The origin of life is rife with exciting speculation, but devoid of known facts or (dis-)provable theories.

““The universe is more than 13 billion years old. That means that even if there have been a thousand civilizations in our own galaxy, if they live only as long as we have been around—roughly ten thousand years—then all of them are likely already extinct. And others won’t evolve until we are long gone”

Broadly speaking this is not an entirely new concept. I vaguely remember this being the premise of Frederick Pohl’s novels where aliens hide in black holes slowing the passage of time until other civilizations develop.

I am pretty sure this wasn’t limited to his writing.

But we are still in the dark. Until we start analyzing exoplanet’s atmospheres for biomarkers, getting their images and conducting wide search for mega engineering projects we simply are left to pure speculative theories.

It is also possible that we see archeology remnants in front of us but interpret it as natural weird phenomena.

Alex T,

You said, “If dinosaurs had built a technological civilization, there would be no traces left, as far as our detection techniques can manage.”

To me, this seems an odd point of view. I can’t even begin to imagine how long it would take Earth to erase all traces of humankind over hundreds of millions of years. All the technological junk we have made. From bricks and arrowheads, now to harder things like metal objects, glass, plastics, cans, auto engines, etc, etc,… into landfills choking with all kinds of non-natural waste that will have some percentage fossilized.

All this stuff will get integrated into the crust and persist…and persist.

I think the result will be a thin stratum of material due to concrete, perhaps enriched with some metal oxides. So that would be detectable. No doubt some parts of the crust would preserve this better than others.Some deeply buried structures not exposed to erosion may even preserve more of the structure, if future explorers could find those locations.

Ocean sediments might even preserve a trace of plastics that might be detectable assuming no organisms evolve to digest the materials.

No doubt our analytic techniques will continue to improve, so that we can detect things we can scarcely imagine today. And if we could observe events in the deep past directly… ?

There’s also our satellites. The first French sat will be up there for 1 million years. LAGEOS 1, with Carl Sagans’ plaque will be in MEO for about 8.4 million years. Our GEO sats may survive a lot longer… granted you’d need to be nearby but any radar pinging should show the Earth surrounded by swarms of debris long after all our surface evidence has eroded/rusted/sub-ducted.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/LAGEOS

Good point. Although I thought Kessler syndrome would leave these objects in tiny pieces over that time. But clearly they would provide proof of a past space using technological society. I wonder if that cloud of metallic debris could be detectable by spectroscopy?

I think this is a good paper. I do wonder about adopting A=0.01 , I mean that’s a good starting point. It has been cloudy for a long time if all the terms in the Drake equation are statistically independent. The term A might have really large error bars, I mean really large uncertainties.

Also normalizing the lifetime of civilization with the parent star lifetime might not fit a universe where there is interstellar flight. A civilization that became independent of its local astronomical environment would make the ‘normalized time’ extremely uncertain.

One keeps in mind they are trying for a lower bound in this paper , I can just see the popular press picking up a number like 10^-22 and putting up a headline that say SCIENTISTS DETERMINE THERE ARE NO EXTRATERRESTRIAL CIVILIZATIONS!

You cannot create data with mathematics, or with assumptions. That’s all they seem to have proven.

They jumbled together a bunch of assumptions (not necessarily good ones, as a few others noted) and calculated an expected value. That’s only part of the story. Statistics can also tell us the quality of that expected value. For such a data-free result the variance equals the expected value. That’s not a useful result. Nor is it data.

It is encouraging that SETI and astrobiology have finally been allowed to sit at the grownups’ table in astronomy (even if they’re still way down at the end sharing a piano bench). One result has been that “life” and even “technological activity” are now something an astronomer can at least speculate about when discussing weird observations — as witness the recent buzz over KIC 8462852.

My personal theory (and I’m putting it out here so I can gloat someday) is that we may discover that something we’ve been seeing for years and explaining as a natural process will turn out to be the work of intelligence. The one-sentence version is “why do advanced civilizations like to arrange stars into big spirals?”

I prefer this formula: i=0.24((p^0.87)/(d^0.4))

Information accuracy about the people of being a ratio of distance to and population of .

Accuracy of information about proxima%=0.24((Population of Proxima (ex. 1 billion aliens)^0.87)/(2.498 x 10^13 miles from earth)^0.4)

Care to do the math?

I agree with Ron S. This is a bad paper, as, despite its erudite tone, it merely substitutes one unknown for another.

Frank and Sullivan’s paper is mistitled, as they do not offer any “new empirical constraint”. Their recourse to probabilistic arguments “to set a lower limit on the probability that technological species have ever evolved anywhere other than on Earth” gives the impression of an increase in our knowledge without delivering one. We already know that probability: in any specified volume of space it is either exactly zero or exactly unity, and until we look we don’t know which.

In my “Parameter Space” paper, I proposed that the Drake Equation and Fermi Paradox should be retired from use. I demonstrated that the Drake Equation applies to only a subset of the possible permutations of our ignorance. (See JBIS, vol.67 no.6, June 2014, p.224-31.) Frank and Sullivan have ignored the possible scenarios in which the Drake Equation is radically simplified to a step function, or is simply invalid (if we are the first to industrialise).

The only way to make genuine progress in this subject is to pursue the work now being done by Icarus Interstellar, and to pursue the expansion of our civilisation to the stage where launching such direct probes of neighbouring planetary systems becomes feasible.

Stephen

Oxford, UK

I have always thought that “L” should be UPGRADED to “L*”, which would include the “continued functionality factor” of a now extinct biological species’ MACHINES. If, for example, Benford Beacons IN SPACE could SELF-REPAIR and remain functional for MILLIONS OF YEARS before the inevitable collision with asteroid debris large enough to destroy them, this would DRAMATICALLY INCREASE THE ODDS of us detecting one in our OWN galaxy. ALSO: The production of biologically destructive dipole antennae artificial dust “blackbox” screens(from Brian Lacki’s recent paper titled: Level III Civilizations [Apparently] Do Not Exist {google it ASAP}) to enclose anything from planetary systems and Kuiper belts to Oort clouds to EVEN ENTIRE GALAXIES could CONTINUE via machine LONG AFTER COMPLETE BIOLOGICAL EXTINCTION HAS OCCURED!! To me, the ODDS GREATLY FAVOR the detection of a mechanically active but biologically dead civilization by either DESIGN(i.e. the EVOLUTION from biological to mechanical intelligence)OR by trajic accident! If, AGAINST INCREDIBLE ODDS, KIC8462852′ lightcurves are NOT of natural origin, it will probably turn out to be the INDIRECT BY-PRODUCT of a VERY LONG DEAD biological species!

But if we are indeed the first, then Lacki’s conclusions are wrong. We may have a bright future ahead of us, it just depends on us, not some ghastly cosmic filter.

+

The uncertainties regarding the emergence of life give this statistical analysis a hollow feeling. The huge numbers of their analysis are equally problematic. We only have evidence of life emerging once. How does their formula change if life similar to earth life is found on Mars (related life)? Or if unrelated life is found on Titan. It would be interesting to see the formulas generate these scenarios.

You are right. In answer to your question: The situation would change dramatically. The discovery of a second form of life would prove beyond reasonable doubt that the f_bt factor is much larger than 10^-22, or even 10^-11. Without such a discovery, the only evidence we have is that none of these A civilizations have ever come here and trampled on our progenitors, despite billions of years of opportunity to do so. And that evidence has to be counted against f_bt being greater than 10^-11.

Interesting paper. As far as I am concerned, the more papers like this that look at the likelihood of our being alone, the better. I think the reason that we have not heard from other civilizations is that the nearest ones are probably billions of light years away. I look to a Tripartite solution to the Fermi Paradox: (i) there is a bottleneck in the formation of life from non-living matter so much so that such an event takes place once per 1000 galaxies, (ii) once life emerges from non-life, there is a bottleneck in the formation of complex life so much so that such an event takes place in perhaps 1 out of every 1 million large galaxies, and (iii) once complex life arises, there is a bottleneck in the complex lifeforms forming a technological civilization so much so that such an event takes place in perhaps 1 out of every 1 billion large galaxies AND, once the technological civilization forms, the laws of physics prevent the creation of any FTL travel or communication. Given that there are ~100 billion large galaxies in the observable Universe, this would mean that there are only about 100 technological civilizations in the entire visible Universe. Further, many of these enormously separated societies might not overlap in time, as Paul mentions the importance of the L factor in their equation.

That would be a very depressing universe.

However the universe and physics don’t care for our feelings.

Personally I think you are a bit too sceptical about emergence of life, my hunch is that it isn’t that rate, most likely uncommon but relatively easy to find in galaxy, but transformation to complex life is much rarer and to technological civilization probably very, very unique.

Still these are only our assumptions, we need more data to base them on. Thankfully we live in a time where some answers will be found out hopefully within a decade or two.

I don’t find it depressing. It is, rather, the only version that allows us a bright future. No big filter, no murderous aliens, lots of available real estate.

Why stop at 100? I find it much more satisfying to think that there is exactly 1 technological civilization in the universe. That would offer an explanation of the size of the universe: The universe is as big as it is because that is what it takes for us to exist.

In other words: A universe could well be smaller, but then that could not be our universe. Our universe could well be larger, but that would be inconsistent with Occam’s razor. One civilization is enough to produce the observed effect, more would be unnecessary complexity.

It was my understanding that the size of the Universe has to do with the underlying cosmological theory. In the case of inflation, for example, the Universe as a whole is very likely much larger than the part we can see, but the exact details regarding how much larger are related to how long inflation lasted and at what energy scale inflation took place. Measurements of Omega_tot tell us that the spatial curvature scale is much larger than the horizon size.

You are right, inflation is what makes our universe so big. Inflation is a very “Occamish” way of making the universe really, really large. It is a parsimonious explanation of how there could be as many planets as needed to get one instance of life.

To clarify: It depends on whether you think the underlying cosmological theory is unique, or whether different theories could be equally valid, for different types of universes. If the former is the case, we are just incredibly lucky that this unique theory creates a universe large and complex enough to contain us. In the latter case, it follows from our existence that the universe we are in has to be one that’s large enough, so only that subset needs to be considered. Theories that allow for inflation are particularly likely to be in that subset, because they can compensate for the astronomical improbability of abiogenesis by an astronomical amount of opportunity.

How rare do you think abiogenesis is?

Once in the universe. The entire universe, not just the observable one. The probability of it happening on any given planet would be the inverse of the number of all “habitable” planets in the universe. I don’t think this number is known, but my guess is it could be anywhere between 10^22 to googolplex. And beyond. Some, I believe, think the universe is of infinite size. That would wreak havoc with my theory, but it would not make it any more likely that we’d run into extraterrestrial life.

So if we detect life elsewhere you view would be that it is due to panspermia (but unlikely if we detect life in other galaxies).

Given our current lack of data, why assume such a low probability of abiogenesis rather than take a Copernican view based on our existence that life is common? Both positions seem equally unlikely to me, although I think that panspermia, despite its low probability by natural means, is likely to occur to some extent.

So what is the basis of your logic that abiogenesis has occurred just once in teh universe?

No. If we detect life elsewhere, there are two possible conclusions: If the life is related to us it means panspermia, as you say, 100%. If the life is unrelated, it means I am wrong and abiogenesis is common. It will be obvious which one is the case.

The Copernican view does not imply that life is common. A single instance of life is consistent with the Copernican view, as long as the “chosen” place is chosen at random, from a distribution that has no obvious center.

I have explained my logic. I will try to summarize:

1) There is a huge gap in complexity between the most complex non-living systems and the most primitive living systems. An exponentially low chance of abiogenesis must therefore be the default assumption.

2) The fact that, or the timing when, life arose on Earth is not evidence, because it is fully explained by observation bias.

3) The only data that we have on the question of whether there is other life is the fact that we have not seen any of it, despite its propensity to go everywhere it can. This data, the significance of which can be argued, nevertheless points towards life being rare.

4) Applying Occam’s razor, and given that there is a large variety of possible universes, we would expect the universe we inhabit to be the least complex one consistent with our existence. If abiogenesis is very rare (see 1), this complexity will be dominated by the need to provide enormous size, in order to balance the low chance of success with a large number of trials (i.e. planets). One success is sufficient to explain the outcome (us), so by Occam, one is going to be it.

Note that this is not proof, it just makes sense to me, and is what I go by in the absence of evidence to the contrary.

This sounds rather like Michael Behe’s argument of “irreducible complexity” to me. He has been shown to be wrong regarding evolution. Is his argument possible for abiogenesis? There are many hints that both metabolism and information storage are self organizing with the right starting components and conditions. Just hints, but certainly enough to suggest that this may eventually provide the solution.

If/when we find extraterrestrial life, and we can determine that a second genesis has happened, then we should have many more clues to how abiogenesis could have occurred. Unfortunately that probably won’t happen in my lifetime.

To some extent, I shudder to admit, my argument is similar to Behe’s “irreducable complexity”. Except, obviously, this irreducability is not absolute. We do know that life can form from non-life, because it has. So, Behe’s argument is proven wrong in principle, but it remains meaningful in suggesting that the probability of abiogenesis is extremely low.

Yes, there are hints that autocatalytical cycles could have gotten some primitive form of evolution started under the right conditions, but the path from there to autonomously reproducing organisms is extremely long. Also, those “conditions” appear extremely unlikely as well, in as far as we can speculate what they might have been.

1. Abiogenesis is an unknown. Since we only have a sample size of 1, and even that is not well understood, it’s difficult to project how common or rare it is in the universe. However, there is the hydrothermal vent theory. From wiki:

[blockquote]

Experimental research and computing modeling indicate that the surfaces of mineral particles inside hydrothermal vents have similar catalytic properties to enzymes and are able to create simple organic molecules, such as methanol (CH3OH) and formic acid (HCO2H), out of the dissolved CO2 in the water.[25][26][/blockquote]

2. Earth is not special. It is a planet consisting of common elements/minerals around a G class star. There is an enormous number of exoplanets and solar systems in the universe, and our observations have only scratched the surface. We know that a multitude of life inhabiting every possible niche, along with intelligent life and civilization, have arisen at least once in the universe. If there are no severe bottlenecks on this development, then why should that not be the case elsewhere? While Occam’s Razor is quite useful, I don’t think it applies here.

It would be like a prehistoric tribe, without contact with other tribes, assuming that they are the only humans in the world. The earth is just large and complex enough to support their tribe, and Occam’s Razor rules out the existence of other tribes and societies. In this case, they’re overlooking the fact that there’s no local exceptionalism to human life and society – if it can happen in one temperate part of the world, it can happen in another. Likewise, without severe bottlenecks, I don’t see why life shouldn’t have arisen multiple times on other planets (the frequency of which is unknown). Considering the discovery of exoplanets, we seem to have a trend against bottlenecks (one proposed bottleneck was that terrestrial planets/solar systems are rare, which has been proven wrong).

3. Our observations are so limited that we can’t make any definite statements on the frequency of exobiology. We haven’t ruled out the existence of simple lifeforms elsewhere in our solar system. While we haven’t found any signals/evidence of ETI, this too is limited. Besides, I believe that intelligent life and civilization is relatively rare compared to the abundance of life.

My equation is: an inverse relationship between the commonality and complexity of life.

4. Again, this depends on whether abiogenesis is a bottleneck, and to what extent. In my view, the existence of civilization faces these hurdles: abiogenesis, complex life, sentient cognition, and social organization (arguably a fifth would be preservation of civilization and avoidance of exinction). The facts are not yet in, but the current state of things supports my inverse theory. I think there is alien life, but civilizations of intelligent aliens will be far less common than simple lifeforms.

(pardon me for messing up the blockquote format yet again. angle brackets, not square brackets!)

To add onto this, Eniac – I fully understand your logic, but I believe you’ve set your filter at the wrong hurdle. Instead of abiogenesis, why shouldn’t it be sentience? According to my inverse theory, sentient beings are like the capstone of the life pyramid. So, it would satisfy Occam’s Razor if the universe was vast and complex enough for intelligent civilization to arise, as this is the rare peak of an enormous biology.

Why abiogenesis as the most likely “big filter”? Because it is the only increase in complexity that is not easily explained by mutation and natural selection. These two “workers of wonder” require life, and thus were not present to help abiogenesis.

That remains to be seen. While what you’re saying is true, our knowledge of abiogenesis is mostly a blank. It is not certain how common or rare it is, or what processes are involved. However,

That’s the conservative estimate. The fact that life on earth seemed to spring up as soon as it possibly could is evidence in my mind that abiogenesis is not an imposing filter. However, with a sample size of 1, this is speculation.

On the other hand, in spite of the variegated complexity, long history, and vast extent of Earth’s life, intelligent life and civilization has only arisen once (as far as we know). This leads me to speculate that sentience is the big filter.

Although we disagree, I appreciate the response.

And why should that be that the universe is exactly big enough to produce precisely 1 civilization, and not 0, 2, 3, 50 or a million?

I can only interprete your assumption as a form of intelligent design lite – the universe designed for us and thus with exactly the properties needed for us and no one but us to exist.

Zero is obviously not an option: We can exclude that based on the evidence. The others (2, 3, 50 or a million) are possible. I reject them based on Occam’s razor, aka parsimony: Given multiple equally valid explanations of an observation, the simplest one is most likely to be correct.

Here is an example: You work at an ice cream stand. Your tipping jar is empty. You leave for 30 minutes and when you return you find one dollar. There are multiple explanations for this: 1) One person might have given a dollar. 2) One person might have given $2 and another person might have stolen one dollar. 3…) An infinity of other, similar explanations.

I think that, despite the large number of possible explanations, you will feel pretty sure you know what happened. You make the parsimonious default assumption, and most often you will be right.

You interpret my assumption wrong: I am not saying that universe was designed for us. That would be nonsensical. By definition, nothing exists outside the universe, much less someone able to design things.

Rather, I am saying, our universe is selected from all possible universes by the posterior observation that we exist. It is Bayesian reasoning, from consequence to cause. The same kind of reasoning that lets you conclude that it must have rained recently when you find the pavement to be wet.

If the universe was infinite, it would contain Boltzmann Brains, i.e. random fluctuations of matter that are exactly like a (my?) brain. However, because a finished brain is ludicrously harder to form by chance than a primitive bacterium, Boltzmann Brains would be a lot rarer than planets with life and evolution and technological civilization. Ludicrously rarer. So, from my point of view, chances are overwhelming that I am a part of the latter, rather than the former. Good thing, too…

Paul:

I don’t think so. If the odds are less than 10^-22, they do, in fact, not favor this. Are you talking about the odds of the odds being so small? That, in my view, makes no sense at all. There are no odds on the odds.

Again, I do not think they do, because there is this one number we do not know, and just because 10^-22 seems small does not make it implausible. Remember, we are talking about the first self-replicating organism arising spontaneously, the chicken or the egg.

You are missing the most important question: Are there lifeforms that have gone beyond their home planet and started to spread across the galaxy?

Abiogenesis need not be a sudden process. It’s entirely possible that it is a drawn-out process during which a clear distinction between life and not-life cannot be made. There could be lots of planets where this process never concluded and forms of proto-life have arisen but never developed into actual life.

I agree. And for all we know about the process (which is practically nothing) it may easily only succeed once in 10^22 trials.

Ron S — “You cannot create data with mathematics, or with assumptions. That’s all they seem to have proven.”

Technically this is correct. However, flipping the coin over, what we have is another paper that helps the detection science end of things narrow down the types of things to look for. Speculation that uses even created data is useful if it is based on reasonable assumptions. It helps define the probabilities of what endeavours will be successful. And frankly we are so blind right now that assumptions based loosely on scientific principles are far better as a starting point than complete guesswork [e.g. Drake.] I expect that in say 25 years hence when we are capable of detecting faint biological signatures in exoatmospheres [bacteria, most likely, rather than E.T.] via spectroscopy that we may stumble upon a correlation [e.g. proximity to nebulae] that were heretofore unknown. Anything that narrows the guesswork.

I believe we are going to find it awfully lonely out there, maybe we will find the occasional swamp rat.