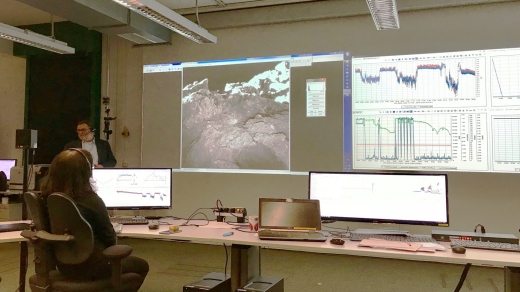

To me, the image below is emblematic of space exploration. We look out at vistas that have never before been seen by human eye, contextualized by the banks of equipment that connect us to our probes on distant worlds. The fact that we can then sling these images globally through the Internet, opening them up to anyone with a computer at hand, gives them additional weight. Through such technologies we may eventually recover what we used to take for granted in the days of the Moon race, a sense of global participation and engagement.

We’re looking at the MASCOT Control Centre at the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) in Cologne, where the MASCOT lander was followed through its separation from the Japanese Hayabusa2 probe on October 3, its landing on asteroid Ryugu, and the end of the mission, some 17 hours later.

Image: In the foreground is MASCOT project manager Tra-Mi Ho from the DLR Institute of Space Systems in Bremen at the MASCOT Control Centre of the DLR Microgravity User Support Centre in Cologne. In the background is Ralf Jaumann, scientific director of MASCOT, presenting some of the 120 images taken with the DLR camera MASCAM. Credit: DLR.

As scientists from Japan, Germany and France looked on, MASCOT (Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout) successfully acquired data about the surface of the asteroid at several locations and safely returned its data to Hayabusa2 before its battery became depleted. A full 17 hours of battery life allowed an extra hour of operations, data collection, image acquisition and movement to various surface locations.

MASCOT is a mobile device, capable of using its swing-arm to reposition itself as needed. Attitude changes can keep the top antenna directed upward while the spectroscopic microscope faces downwards, a fact controllers put to good use. Says MASCOT operations manager Christian Krause (DLR):

“After a first automated reorientation hop, it ended up in an unfavourable position. With another manually commanded hopping manoeuvre, we were able to place MASCOT in another favourable position thanks to the very precisely controlled swing arm.”

MASCOT moved several meters to its early measuring points, with a longer move at the last as controllers took advantage of the remaining battery life. Three asteroid days and two asteroid nights, with a day-night cycle lasting 7 hours and 36 minutes, covered the lander’s operations.

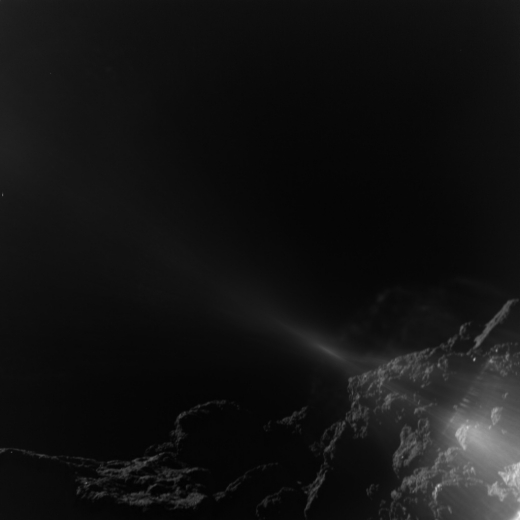

Image: The images acquired with the MASCAM camera on the MASCOT lander during the descent show an extremely rugged surface covered with numerous angular rocks. Ryugu, a four-and-a-half billion year-old C-type asteroid has shown the scientists something they had not expected, even though more than a dozen asteroids have been explored up close by space probes. On this close-up, there are no areas covered with dust — the regolith that results from the fragmentation of rocks due to exposure to micrometeorite impacts and high-energy cosmic particles over billions of years. The image from the rotating MASCOT lander was taken at a height of about 10 to 20 meters. Credit: MASCOT/DLR/JAXA.

The dark surface of Ryugu reflects about 2.5 percent of incoming starlight, so that in the image below, the area shown is as dark as asphalt. According to DLR, the details of the terrain can be captured because of the photosensitive semiconductor elements of the 1000 by 1000 pixel CMOS (complementary metal-oxide semiconductor) camera sensor, which can enhance low light signals and produce usable image data.

Image: DLR’s MASCAM camera took 20 images during MASCOT’s 20-minute fall to Ryugu, following its separation from Hayabusa2, which took place at 51 meters above the asteroid’s surface. This image shows the landscape near the first touchdown location on Ryugu from a height of about 25 to 10 meters. Light reflections on the frame structure of the camera body scatter into the field of vision of the MASCAM (bottom right) as a result of the backlit light of the Sun shining on Ryugu. Credit: MASCOT/DLR/JAXA.

We now collect data and go about evaluating the results of MASCOT’s foray. The small lander had a short life but it seems to have delivered on every expectation. As Hayabusa2 operations continue at Ryugu, we’ll learn a great deal about the early history of the Solar System and the composition of near-Earth asteroids like these, all of which we’ll be able to weigh against what we find at asteroid Bennu when the OSIRIS-REx mission reaches its target in December.

Image: MASCOT as photographed by the ONC-W2 immediately after separation. MASCOT was captured on three consecutively shot images, with image capture times between 10:57:54 JST – 10:58:14 JST on October 3. Since separation time itself was at 10:57:20 JST, this image was captured immediately after separation. The ONC-W2 is a camera attached to the side of the spacecraft and is shooting diagonally downward from Hayabusa2. This gives an image showing MASCOT descending with the surface of Ryugu in the background. Credit: JAXA, University of Tokyo, Kochi University, Rikkyo University, Nagoya University, Chiba Institute of Technology, Meiji University, University of Aizu, AIST.

Bear in mind that the the 50th annual meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) is coming up in Knoxville in late October. Among the press conferences scheduled are one covering Hayabusa2 developments and another the latest from New Horizons. The coming weeks will be a busy time for Solar System exploration.

“Anyone with a computer at hand”. Yes I agree that is fantastic. Everyone with a smart phone has access to this data anywhere anytime virtually everywhere on the planet. However, global availability cannot be equated with global exposure. Even with smart phone in hand the story will only register if its shared. Astro stories like nonmedical primary science stories in general get widest coverage when a wow effect is created. And that too often relies on novelty. The participation and engagement you refer to is otherwise restricted to the nerds who actively seek these stories. Its always been that way. 1972 Apollo died because…”been there. done that”. Joe and Josephine Blow don’t care about the science only the spectacle. Sad but true.

That is a good point, but there is a big difference between 1972 and today, here in the Philippines the locals do not have books, magazines or even a newspaper is hard to find. TV is just becoming the norm for most of the community but, android phones have just become common and cheap in the last two years. Students have them in HS and collage but most use them for FB, but eventually they will use it to learn and study. That is making a big difference very quickly in the poorer parts of the country – a real revolution is happening that will change the whole of human understanding and most in the 1st world have very little inkling of what is happening!

The mainstream media does not focus on events like space and science unless something dramatic happens (like this morning’s Soyuz rocket launch abort – the two space travelers are okay) or there is some kind of political tie-in, etc.

Even the supposedly enlightened NPR seldom covers space and science and when they do, the stories usually come at the end of their news hours. Then they often do it in a humorous manner, with one of their “funny” reporters. They also ask questions which belie the fact that not only does the reporter not know their subject matter, but they did little research on it, nor do they intend on learning about it either then or in the future.

I get almost all my space and astronomy news from the Internet. That can also be a mixed bag, but I know how to filter the wheat from the chaff. The problem is, does Joe/Jane Public know the difference?

Our public education system is also to blame, but that is another story.

Hmm.. Is there any chance we are looking at an old, boiled – off comet? Thinking of the Rosetta expedition, how would a comet, an icy body, look after all the ice has disappeared? Gas from the sublimation would vent into space and eject the dust present along the way, leaving coarser structure on the surface of the increasingly dry body?

It looks to me more like the tailings left over from the last interstellar mini-black-hole dredging operations 65 million years ago. :-o

In one of those old science fiction Heavy Metal magazine wannabes from the late 1970s, I recall a story about two planetoid prospectors coming upon a perfect black sphere in Sol’s Main Planetoid Belt. They had never seen such a thing before and naturally wanted to know what it was.

Eventually they and the readers discover the sphere is what was once the core of an extinct Jovian world that existed between Mars and Jupiter: The Planetoid Belt is what is left of its existence.

Unfortunately for the two astronaut-miners, they realize this just before their laser drill punctured the sphere (they were naturally trying to get a sample of its interior) and discovered that the object was under tremendous pressure, which the laser beam released in an instant. The End.

It is amazing that the more we know (the increasing volume of a sphere), the more we realize what we don’t know (the increasing surface of the sphere: the interface with the known unknowns). Yet beyond the surface may lie an infinitude of unknown unknowns. Exploring an asteroid is yet another infinitesimally small step into the unknowns, helping chart a path into those regions. As did the “seven-league boots” of the Hubble Ultra-Deep Field.

This earlier image makes me think of heated carbon. It may be a trick of the lighting, but those bright flecks could be carbon that has crystallized after charring or coal that is cleanly broken revealing a flat face.

Like Jens, I also wondered if it is a dead comet, a dusty surface of debris insulating a still frozen core. Using the Wikipedia data for mass and diameter, I calculate that the average density is approximately 1. 4 g/cm^3 (Assuming Ryugu as a sphere) to 2.75 g/cm^3 (assuming it is 2 cones). Comet densities are very low ~ 0.5 – 0.6 g/cm^3, whilst carbonaceous meteorites are 2.5-3.5 g/cm^3. This suggests that most likely Ryugu is a solid carbonaceous chondrite and not a dead comet.

Just wonder what the temperature variation is between night and day and as it orbits around the sun? I suppose they used coal burning dredges. :-)

A large planetary body inferred from diamond inclusions in a ureilite meteorite.

“Asteroid 2008 TC3 fell in 2008 in the Nubian desert in Sudan1, and the recovered meteorites, called Almahata Sitta, are mostly dominated by ureilites along with various chondrites2. Ureilite fragments are coarse grained rocks mainly consisting of olivine and pyroxene, originating from the mantle of the ureilite parent body (UPB)3 that has been disrupted following an impact in the first 10?Myr of the solar system3. High concentrations of carbon distinguishes ureilites from all other achondrite meteorites3, with graphite and diamond expressed between silicate grains.

There are three mechanisms suggested for diamond formation in ureilites: (i) shock-driven transformation of graphite to diamond during a high-energy impact4, (ii) growth by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) of a carbon-rich gas in the solar nebula5, and (iii) growth under static high-pressure inside the UPB6. Recent observation7 of a fragment of the Almahata Sitta ureilite (MS-170) revealed clusters of diamond single crystals that have almost identical crystallographic orientation, and separated by graphite bands. It was thus suggested that individual diamond single crystals as large as 100??m existed in the sample, which have been later segmented through graphitization7. The formation of such large single-crystal diamond grains along with ?15N sector zoning observed in diamond segments7 is impossible during a dynamic event8,9 due to its short duration (up to a few seconds10), and even more so by CVD mechanisms11, leaving static high-pressure growth as the only possibility for the origin of the single-crystal diamonds.”

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-03808-6

https://www.asteroidmission.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/BennuRyuguComparison.png

Type B and C – interesting to see what Bennu is, as it’s a B-type asteroid.

Jason Davis • October 19, 2018

Collecting a sample from asteroid Ryugu is going to be dicey

The scientists and engineers behind Japan’s Hayabusa 2 mission are giving themselves more time to prepare for a hair-raising sample collection from asteroid Ryugu’s surface.

Hayabusa 2 arrived at Ryugu in June, deployed three hopping rovers in September, and dropped a toaster-sized lander earlier this month. The spacecraft was scheduled to touch down on the asteroid and collect a sample later this month, but that has been delayed to early 2019 as Ryugu and Hayabusa 2 prepare for solar conjunction, a roughly month-long blackout period where they are on the opposite side of the sun from Earth.

“Once the angle between the spacecraft, Earth and Sun is less than about 6 degrees, the radio noise from the Sun interferes with communication too much to send a signal to Hayabusa2,” said Elizabeth Tasker, an associate professor at the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA. “As that angle shrinks even more, there is also a point where the Sun is physically in the way.”

JAXA officials say the delay will give them more time to study Ryugu’s surface in preparation for touchdown, while learning more about the performance of their spacecraft.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/jason-davis/ryugu-sample-dicey.html

Japan’s asteroid rovers continue to send back amazing images of its alien surface

Mike Wehner

December 13, 2018 at 9:02 PM

It’s been a couple of months since the Japanese space agency (JAXA) deployed robots to the surface of the asteroid known as Ryugu. The Hayabusa-2 “mothership” sent the bots down to examine the space rock’s surface and send back readings to Earth, and we got to see the images shortly after they arrived.

Now, as JAXA prepares for the most daring maneuver of the entire mission — a touchdown that will allow Hayabusa-2 to snag a sample of the rock’s surface before heading back to Earth — the space agency is showing off more of the awesome images snapped by its rovers.

Full article and new images here:

https://bgr.com/2018/12/13/hayabusa-2-probe-jaxa-ryugu-asteroid-surface/

The two hopping Hayabusa 2 rovers have new names….

https://www.space.com/42753-japan-hayabusa2-asteroid-rovers-names.html

To quote:

To date, the duo have been known as MINERVA-II1A and MINERVA-II1B, which are more designations than names. But that has changed: MINERVA-II1A is now called HIBOU, which is short for “Highly Intelligent Bouncing Observation Unit” and also French for “horned owl,” while its sibling is OWL (“Observation unit with intelligent Wheel Locomotion”), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) officials announced yesterday (Dec. 13).