The spectacular success of New Horizons inevitably leads to questions about what an orbiter at Pluto/Charon might accomplish. It’s heartening that NASA has funded the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) to look further into the matter, the Institute having already examined the question on its own. Now a Pluto orbiter becomes one of ten mission studies NASA is sponsoring as we look toward the next National Academy Planetary Science Decadal Survey. Beginning in 2020, the survey will outline science objectives and recommend missions over a ten year period.

The NASA decision leverages all the work SwRI has put into the Pluto orbiter concept, and brings the focus to what we might accomplish with such a mission that a flyby could not. Particularly significant will be the choice of science instruments, which a spacecraft achieving global coverage will demand. And because we have a system at Pluto with five moons, we have a range of targets that can be subjected to detailed study. There is even the possibility of taking the mission to other targets, as New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern explained:

“In an SwRI-funded study that preceded this new NASA-funded study, we developed a Pluto system orbital tour, showing the mission was possible with planned capability launch vehicles and existing electric propulsion systems. We also showed it is possible to use gravity assists from Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, to escape Pluto orbit and to go back into the Kuiper Belt for the exploration of more KBOs like MU69 and at least one more dwarf planet for comparison to Pluto.”

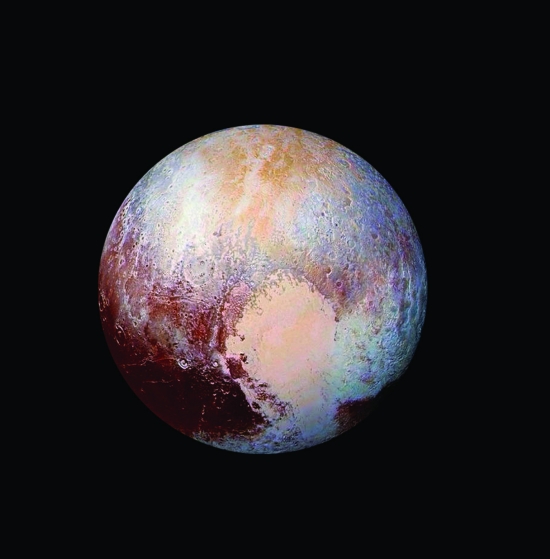

Image: To follow up on NASA’s New Horizons mission that revealed Pluto’s “heart,” SwRI is studying a new Pluto orbiter mission for NASA. SwRI has shown it is possible to orbit Pluto and then escape orbit to tour additional dwarf planets and Kuiper Belt Objects. Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI.

New Horizons carries seven instruments, all of which are still functioning well, as we learned from Stern in his latest PI’s Perspective. Having flown past Ultima Thule (2014 MU69), New Horizons continues to explore the Kuiper Belt, and it will be instructive to see how long it continues to return data. The Voyagers have demonstrated longevity far beyond the expectations of those who built them, Right now the spacecraft is continuing to return data on the Ultima Thule flyby, a process that will last another year or so, according to Stern, but New Horizons is also continuing to observe KBOs as it moves ever further out..

The seven scientific instruments aboard the spacecraft have just been put through a thorough calibration, the first such campaign run since just before the Pluto/Charon flyby. As with the Ultima Thule data, the complete calibration results will be returned with the dataflow over the next year, though Stern says the instruments ‘performed flawlessly.’ The crucial Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) has received a software upgrade designed to detect fainter targets than before as well as to enable longer exposures. The new capability will be in place by December for further Kuiper Belt exploration.

We still don’t have a dedicated mission to the interstellar medium, meaning one with an instrument package expressly designed for operations beyond the heliosphere, but we do have continuing dust and plasma observations of the outer heliosphere from New Horizons. This is useful stuff, because we are building a dataset that complements what the two Voyagers have given us, though the New Horizons instrument package is more capable. Planetary scientists will take advantage of observations like these in learning more about how the surfaces of KBOs and dwarf planets are affected by the environment through which they orbit.

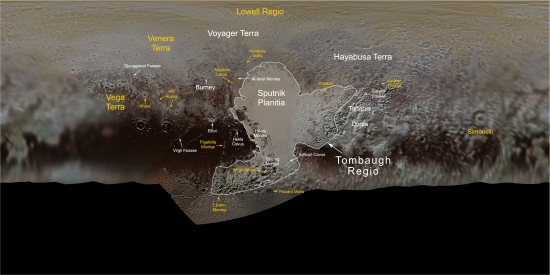

A number of science papers on Pluto/Charon and Ultima Thule are about to be submitted, with dozens of new results reported at the recent Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Geneva. You can see that New Horizons is very much an ongoing mission, even as we look toward the benefits of a Pluto orbiter that is at least under study not just at SwRI but NASA. The continued naming of Pluto surface features is a reminder of how much we’ve learned, but imagine how we can fill out these young maps with features yet to be observed in detail.

Image (click to enlarge): This map, compiled from images and data gathered by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft during its flight through the Pluto system in 2015, contains Pluto feature names approved by the International Astronomical Union. Names from the newest round of nominations, approved in 2019, are in yellow. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Ross Beyer.

Looks like the alignment for Jupiter and Saturn is pretty good right now for a gravity assist, but in maybe 12 years only Jupiter could be any help.

So two questions instantly arose from me in reading this article. Wouldn’t it be a wise thing to construct the spacecraft that aside from it’s obvious scientific collection efforts could also be dedicated to doing automatic hardware repair while at great distances from the earth say at distances that represent Pluto and beyond.

The thinking behind this is that if you recall, Project Daedalus was designed with the objective in mind that it could be a self repairing robotic probe. Shouldn’t we have at this point in time begun to explore the concept of a self repairing robotic probe in actuality ? It seems like such a proof of concept on an actual probe in deep space would be a learning experience for future missions that would be out of contact with earth and would further serve as a benchmark as to what problems we could be reasonably expected to encounter.

The second thing that I wanted to ask was whether or not there had been any gravitational mapping of the gravitational field of Pluto, even though the flyby was a very short extent there would have been I would assume some indication of what the expected gravity field would be in a mathematically and physically develop sense. Does anyone know if any kind of even partial gravity model was developed for Pluto ?

Seems like so long ago that the last planetary decadal was released. And there are still 3 years to wait for the next one.

A Pluto Orbiter will be way down the list I’m afraid.

What should the top planetary priority be?

In terms of public and political interest exobiology seems to be currently dominating the discourse well ahead of all other subsets of planetology. However, despite the political wish to fund a mission that discovers “alien life”, we all know that biosignatures are the maximum we’re going to get from Europa even with its putative plumes and even with a lander. For a variety of reasons there will be no life detection there without direct ocean contact. Read cryobot.

Enceladus at least offers the meager chance of surface bioremnant detection. An Enceladus (plume)ice sample return mission (Stardust style or via lander) seems the obvious first choice in the run for the prize of first exobio detection.

But, the odds are long even for direct ice extraction.

If we set ourselves the goal of finding a second emergence of life that is clearly independent of Earth, then in the absence of plume ice bound biomass, only the development and deployment of a cryobot/submarine combination has a chance to succeed. This must be clearly communicated to the political class. With all due respect for John Culberson’s efforts visavis Europa, I suspect he thought his funding could achieve the ultimate detection. That illusion helped at least secure funding for Clipper. But, the scientific lobbying for funding was a little disingenuous. At the least the potential of the results was played up. We need to address the search for life in the solar system more candidly. Clipper is a necessary first step but will not find life. We now need to prioritize the development of the necessary tools and techniques needed to reach ocean world water.

The irradiated surface of Europa won’t give us even a fragment of a cell and if the Enceladus plume ice shows nothing that’s it for the “easy” routes.

Recent NASA budgets make this a non-starter, as it should be. We have been there and learned much, but it is very far away and we have much more important missions to accomplish in our backyard. The water-ice hidden in Shackleton crater at the lunar south pole should be priority number one, two and three. Free rocket fuel in a gravity well that allowed Apollo astronauts to achieve lunar orbit in something the size of an SUV holds the potential to open the solar system to humanity.

Good point!

We’d learn a Lot about building functional long-range spacecraft if we could get an orbiter out there And slow it down to get it into orbit all within a reasonable number of years. Not to mention then moving on to some other target(s).

Surely a Uranus or Neptune orbiter would be a higher priority.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NASA_Uranus_orbiter_and_probe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neptune_Orbiter

The Cassini mission showed how it can be done at Saturn. Such a successful mission.

Earlier this year a Neptune flyby proposal was made by the JPL under the name “Trident” for inclusion in the Discovery program. The concept includes flybys of Jupiter and Neptune with a focus on Neptune’s largest moon, Triton.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trident_(spacecraft)

– Triton , which is almost certainly a captured Kuiper Belt Object too. As to Trident surely the old axiom, flyby, orbiter, lander applies ?

In terms of Pluto how long would an erstwhile orbiter take to travel with enough braking factored in en route to allow capture by that dwarf planet’s tiny gravity. Twenty years ? Atleast. And to what end.mThanks to New Horizons and Dawn we have now had both flyby and orbiting surveys of three dwarf planets and an additional KBO . Time to look elsewhere .

I’m sure the upcoming Decadal will finally have an Ice Giant Orbiter in pride of place – planetary science wise anyway . Jupiter gravity assists open for both Uranus and Neptune from 2029-2031 and SLS could get a probe to either in under ten years ( 8 for Uranus) – even without promising but untested atmospheric braking on arrival.

The NASA Outer Planets Advisory Group, OPAG, have priposed various mission concepts for either with decent science for around $3 billion. Collaboration with other space agencies will expand this further whilst capping costs to NASA. Gold plated flagships like Galileo and Cassini I fear are beyond NASA’s capacity alone anymore. ( even cost limited Clipper was largely driven by Culberson and Congress) With such planets likely the most common type in the galaxy, close up exploration is surely a sine qua non with Cassini style extended moon surveys a nice bonus .

I reckon an Enceladus “life finder” will be the target of a future New Frontiers mission. Utilising instrument flight spares and design heritage from Europa Clipper, New Horizons and Dawn to create a cut price low energy science payload supported by a single MMRTG. Unless Nasa mission approvers change their conservative attitude to ultra high performance solar arrays , like ROSAT, at 9 AU .

I agree. Planing for a Pluto orbiter is fine, as developing the means to reach outer system targets as fast as possible while also then slowing enough for orbital insertion will be a very valuable skill set. But such a mission at this point in our exploration of our system while neither of the Ice Giants in our system have yet to have received in depth attention seems miss directed. A mission to Neptune seems very attractive, as in addition to an Ice Giant we would be able to study another Kuiper belt object (it’s captured moon Triton).

My thought exactly: an argument against visiting Uranus/Neptune was always that it’s more difficult/costly to do orbital insertion then with Jupiter/Saturn. Now that Pluto is reconsidered, what happened to these arguments? How would a Pluto orbital insertion now not be a problem, or be easier to solve?

We can learn a lot from comparing Triton with Pluto, and Triton is also an active world with clouds and a young surface.

I see that the Pluto orbiter would use the Dawn method of jumping from object to object, which seems hardly realistic to me, seeing the larger distances between objects in the Kuiper Belt unless we would have the patience to approach this a multi-generational mission: escaping the Pluto-Charon system with gravity assist can only be so powerful.

(The achievement of this proposed Pluto plan would be monumental, but we have still some leaps to make before doing that, what I would actually like to see is for the far future is a ‘Voyager-like’ plan to visit a string of Kuiper belt objects if there’s an interesting alignment coming up.)

If I recall correctly, the Pluto New Horizons departed on an Atlas V with, as noted above, a Jupiter and Saturn alignment for a boost.

In the background of this discussion, there is the problem of setting a mission which requires propulsion performance – and allocating resources to both the mission and the means to perform it. A decadal survey has its eyes on objectives such as exploring specific places and then there is pie of a certain size.

No problem? Then why was there such stagnation in propulsion for many years? In the 1990s, Soviet technology was imported into NASA programs and not exploited remarkably well, considering that RD-180 and other engines were not licensed for manufacture or recovered after flight.

Currently, there are a number of new main propulsion systems associated with the larger commercial space programs. Some of them were result of finally building concepts talked about for a long time – and partly due to the arrival of 3-d printing or additive manufacturing applied to the alloys required for high performance rocket engines.

Additionally, solar electric propulsion is not going to cut it headed to Pluto. A great deal can be done with it inside the snow line, but the

capabilities to explore gas giant planets or Pluto is curtailed considerably without a high thrust, high specific impulse system that can run in the dark.

That might be a matter more of public trust in lobbing something like that into orbit above our heads, but unless something like that can

be arranged, then Falcon Heavy or SLS capabilities might be the limiter on outer planet explorations with chemical upper stages. And lithium batteries, I guess.

And, of course, this issue becomes even more acute with interstellar studies.

I suspect that someday, if we can get off this globe to any substantial degree, some of the propulsion systems we really want to try out can be better built and tested in some of those already vacated regions in the solar system.

It’s a conundrum, of course. And I suppose a time traveler going back to the 19th century insisting that aluminum was essential to air travel. Or commercial distribution of products as fragile as bananas thousands of miles away from where they are grown.

How did they do it? Maybe they just backed into these infrastructures?