James Gunn may have been the first science fiction author to anticipate the ‘new Venus,’ i.e., the one we later discovered thanks to observations and Soviet landings on the planet that revealed what its surface was really like. His 1955 tale “The Naked Sky” described “unbearable pressures and burning temperatures” when it ran in Startling Stories for the fall of that year. Gunn was guessing, but we soon learned Venus really did live up to that depiction.

I think Larry Niven came up with the best title among SF stories set on the Venus we found in our data. “Becalmed in Hell” is a 1965 tale in Niven’s ‘Known Space’ sequence that deals with clouds of carbon dioxide, hydrochloric and hydrofluoric acids. No more a tropical paradise, this Venus was a serious do-over of Venus as a story environment, and the more we learned about the planet, the worse the scenario got.

But when it comes to life in the Venusian clouds — human, no less — I always think of Geoffray Landis, not only because of his wonderful novella “The Sultan of the Clouds,” but also because of his earlier work on how the planet might be terraformed, and what might be possible within its atmosphere. For a taste of his ideas on terraforming, a formidable task to say the least, see his “Terraforming Venus: A Challenging Project for Future Colonization,” from the AIAA SPACE 2011 Conference & Exposition, available here. But really, read “The Sultan of the Clouds,” where human cities float atop the maelstrom:

“A hundred and fifty million square kilometers of clouds, a billion cubic kilometers of clouds. In the ocean of clouds the floating cities of Venus are not limited, like terrestrial cities, to two dimensions only, but can float up and down at the whim of the city masters, higher into the bright cold sunlight, downward to the edges of the hot murky depths… The barque sailed over cloud-cathedrals and over cloud-mountains, edges recomplicated with cauliflower fractals. We sailed past lairs filled with cloud-monsters a kilometer tall, with arched necks of cloud stretching forward, threatening and blustering with cloud-teeth, cloud-muscled bodies with clawed feet of flickering lightning.”

Published originally in Asimov’s (September 2010) and reprinted in the Dozois Year’s Best Science Fiction: Twenty-Eighth Annual Collection, the story depicts a vast human presence in aerostats floating at the temperate levels. Landis has explored a variety of Venus exploration technologies including balloons, aircraft and land devices, all of which might eventually be used in building a Venusian infrastructure that would support humans.

We’ve already seen that Carl Sagan had written about possible life in the Venusian atmosphere, and an even more ambitious Paul Burch considered using huge mirrors in space to deflect sunlight, generate power, and cool down the planet. Closer to our time, an internal NASA study called HAVOC, a High Altitude Venus Operational Concept based on balloons, was active, though my understanding is that the project, in the hands of Dale Arney and Chris Jones at NASA Langley, has been abandoned. Maybe the phosphine news will give it impetus for renewal. The Landis aerostats would be far larger, of course, carrying huge populations. I have to wonder what ideas might emerge or be reexamined given the recent developments.

Image: Artist’s rendering of a NASA crewed floating outpost on Venus

With Venus so suddenly in the news, I see that Breakthrough Initiatives has moved swiftly to fund a research study looking into the possibility of primitive life in the Venusian clouds. The funding goes to Sara Seager (MIT) and a group that includes Janusz Petkowski (MIT), Chris Carr (Georgia Tech), Bethany Ehlmann (Caltech), David Grinspoon (Planetary Science Institute) and Pete Klupar (Breakthrough Initiatives). The group will go to work with the phosphine findings definitely in mind. Pete Worden is executive director of Breakthrough Initiatives:

“The discovery of phosphine is an exciting development. We have what could be a biosignature, and a plausible story about how it got there. The next step is to do the basic science needed to thoroughly investigate the evidence and consider how best to confirm and expand on the possibility of life.”

Phosphine has been detected elsewhere in the Solar System in the atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn, with formation deep below the cloud tops and later transport to the upper atmosphere by the strong circulation on those worlds. Given the rocky nature of Venus, we’re presumably looking at far different chemistry as we try to sort out what the ALMA and JCMT findings portend, with exotic and hitherto natural processes still possible. On that matter, I’ll quote Hideo Sagawa (Kyoto Sangyo University, Japan), who was a member of the science team led by Jane Greaves that produced the recent paper:

“Although we concluded that known chemical processes cannot produce enough phosphine, there remains the possibility that some hitherto unknown abiotic process exists on Venus. We have a lot of homework to do before reaching an exotic conclusion, including re-observation of Venus to verify the present result itself.”

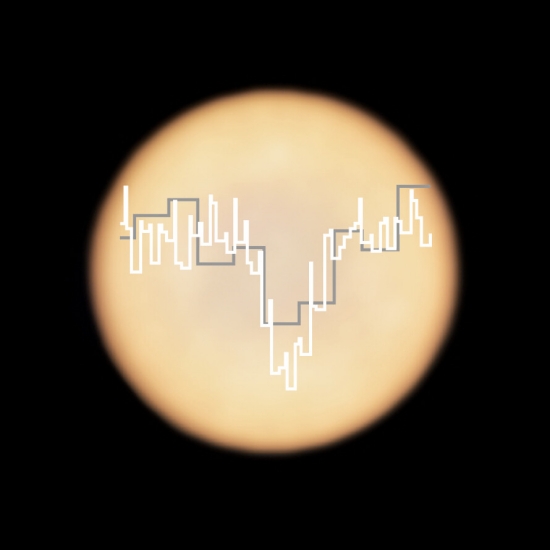

Image: ALMA image of Venus, superimposed with spectra of phosphine observed with ALMA (in white) and JCMT (in grey). As molecules of phosphine float in the high clouds of Venus, they absorb some of the millimeter waves that are produced at lower altitudes. When observing the planet in the millimeter wavelength range, astronomers can pick up this phosphine absorption signature in their data as a dip in the light from the planet. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), Greaves et al. & JCMT (East Asian Observatory).

I’ll close with the interesting note that the BepiColombo mission, carrying the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and Mio (Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, MMO), will be using Venus flybys to brake for destination, one on October 15, the other next year on August 10. It has yet to be determined whether the onboard MERTIS (MErcury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer) could detect phosphine at the distance of the first flyby — about 10,000 kilometers — but the second is to close to 550 kilometers, a far more promising prospect. You never know when a spacecraft asset is going to suddenly find a secondary purpose.

Image: A sequence taken by one of the MCAM selfie cameras on board of the European-Japanese Mercury mission BepiColombo as the spacecraft zoomed past the planet during its first and only Earth flyby. Images in the sequence were taken in intervals of a few minutes from 03:03 UTC until 04:15 UTC on 10 April 2020, shortly before the closest approach. The distance to Earth diminished from around 26,700 km to 12,800 km during the time the sequence was captured. In these images, Earth appears in the upper right corner, behind the spacecraft structure and its magnetometer boom, and moves slowly towards the upper left of the image, where the medium-gain antenna is also visible. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0.

And keep your eye on the possibility of a Venus mission from Rocket Lab, a privately owned aerospace manufacturer and launch service, which could involve a Venus atmospheric entry probe using its Electron rocket and Photon spacecraft platform. According to this lengthy article in Spaceflight Now, Rocket Lab founder Peter Beck has already been talking with MIT’s Sara Seager about the possibility. Launch could be as early as 2023, a prospect we’ll obviously follow with interest.

A final interesting reference re life in the clouds, one I haven’t had time to get to yet, is Limaye et al., “Venus’ Spectral Signatures and the Potential for Life in the Clouds,” Astrobiology Vol. 18, No. 9 (2 September 2018). Full text.

Thanks for posting the Limaye et al. paper. You are one of the few. It was the first to propose a number of mechanisms for a microbial life cycle built upon the work of many others. Reading some of the quotes from the Phosphine team you might be led to believe that Seager et al’s Astrobiology paper was the first. It was not.

Venus is the Best Place in the Solar System to Establish a Human Settlement (2003)

In a brief paper prepared for the February 2003 Space Technology and Applications International Forum in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Landis made a compelling case for Venus, not the Moon, nor Mars, nor a twirling sphere, torus, or tube in open space, as the ideal place to establish an off-Earth human settlement.

Specifically, he set his sights on the Venusian atmosphere just above the dense sulfuric-acid clouds. Landis called it “the most earth-like environment (other than the Earth itself) in the Solar System.”

Full article here:

http://spaceflighthistory.blogspot.com/2020/08/venus-is-best-place-in-solar-system-to.html

Various quotes:

The twin three-meter-diameter, helium-filled balloons deployed between 50 and 55 kilometers (34 and 31 miles) above the Venusian surface — that is, just above the cloud-tops, in the zone Landis saw as promising for human settlement. Their small instrument payloads transmitted data for approximately two days — until they exhausted their chemical batteries.

In that time, the balloons rode the carbon dioxide winds from their deployment points over the nightside into bright Venusian daylight. The Vega 2 balloon travelled about 11,100 kilometers (6900 miles) and the Vega 1 balloon travelled 11,600 kilometers (7210 miles). When their instrument payloads exhausted their batteries, the balloons carrying them showed no sign of imminent failure. They might have lasted for months or even years.

…

The fragile balloons could last so long because 50 kilometers above Venus, just above the cloud tops, the temperature ranges from between 0° C to 50° C (32° F to 122° F) and the atmospheric pressure approximates Earth sea-level pressure. A thin fabric cover was sufficient to shield each balloon from sulfuric acid droplets drifting up from the cloud layer.

Venus settlers would float where Vega 1 and Vega 2 floated, but Landis rejected helium balloons. He noted that, on Venus, a human-breathable nitrogen/oxygen air mix is a lifting gas. A balloon containing a cubic meter of breathable air would be capable of hoisting about half a kilogram, or about half as much weight as a balloon containing a cubic meter of helium. A kilometer-wide spherical balloon filled only with breathable air could in the Venusian atmosphere lift 700,000 tons, or roughly the weight of 230 fully-fueled Saturn V rockets. Settlers could build and live inside the air envelope.

The air envelope supporting a settlement would not necessarily maintain a spherical form. Lack of any pressure differential would allow the gas envelope to change shape fluidly over time. It would also limit the danger should the envelope tear. The internal and external atmospheres would mix slowly, so the settlement atmosphere would not suddenly turn poisonous, nor would the settlement rapidly lose altitude.

A repair crew would not require pressure suits, Landis explained. They would, of course, need air-tight face masks to provide them with oxygen and keep out carbon dioxide; adding goggles and unpressurized protective garments would keep them safe from acid droplets.

Acid droplets in the Venusian atmosphere would no doubt be annoying, but Venus would lack the frequent toxic dust storms of Mars. Orbiting nearly twice as close to the Sun as does Mars, a Venusian solar farm would have available four times as much solar energy at all times — and with no dust storms to get in the way. Landis noted that solar panels could collect almost as much sunlight reflected off the bright Venusian clouds as they could from the Sun itself.

Mars, the Moon, and free-space habitats all must contend with solar and galactic-cosmic ionizing radiation. A settlement 50 kilometers above Venus, by contrast, could rely on the Venusian atmosphere to ward off dangerous radiation. Radiation exposure would be virtually identical to that experienced at sea level on Earth.

Many aspiring space settlers assume that humans and the plants and animals they rely on (or simply like to have around) will be able to live in one-sixth or one-third Earth gravity — the gravitational pull felt on the Moon and on Mars, respectively — with no ill effects. The hard reality, however, is that no one knows if this is true. It is possible that astronauts living in hypogravity — that is, gravity less than one Earth gravity — will experience health effects similar to those they experience during long stays in microgravity (for example, on board the International Space Station).

Venus is nearly as dense and as large as Earth, so its gravitational pull is about 90% that of humankind’s homeworld. The likelihood that hypogravity will make long-term occupancy unhealthful might thus be reduced.

The Venusian atmosphere is rich in resources needed for life and the Venusian surface, while hellish, would lay only 50 kilometers away from the settlement at all times. Landis suggested that Venus settlers might use a suspended super-strong cable to lift silicon, iron, aluminum, magnesium, potassium, calcium, and other essential chemical elements to the floating settlement. He noted that laboratory experiments aimed at producing robots hardy enough to function on Venus for long periods had already begun; operators might use such rovers to remotely mine the surface from the comfort of the floating settlement.

…

As the journeys of the twin Vega balloons illustrate, Venus atmosphere settlements would ride fast winds. Those near the equator would circle the planet every four days. This would mean, Landis explained, that they would experience a day/night pattern of two days of darkness followed by two days of light. He expected that settlements eager for a more Earth-like lighting pattern could migrate to the Venusian circumpolar regions, where a circuit around the planet would be shorter.

If many “cloud cities” were eventually established in the atmosphere of Venus, then a preference for the poles might lead to crowding. If, on the other hand, any latitude were fair game, then Venus would offer for settlement a total area 3.1 times Earth’s land area — that is, more than three times greater than the surface area of Mars. Landis wrote that, eventually, a “billion habitats, each one with a population of hundreds of thousands of humans, could. . . float in the Venus atmosphere.”

In other words, as much as the Venusian atmosphere creates problems for those attempting to visit the planet’s surface, the thick, rich air also has its advantages over other worlds which either have a very thin air envelope or essentially none at all.

Venus definitely deserves a second and third chance with humanity.

Just don’t go outside the envelope without an acid-resistant full environmental suit. Maybe something like a thick polyethylene positive pressure suit would suffice. And don’t fall…

I agree Alex, I would rather live at the south pole in a nice warm habitat than be floating above a furnace. This floating cities of Venus idea is ridiculous at face value. PS 60 tons of space crap fall to earth every day…sounds like a Venusian Hindenburg in the making.

A thought question on terraforming Venus. Would it be technically possible to literally siphon off most of the atmosphere to space using technology derived from space elevator concept? I can envision the floating cities idea being used to support hundred to thousand km long tubes that would initially pump then vent the gas to space. Would the gas just fall back? If so, maybe it would take a very long time? Would it disperse if vented high enough? Would the solar wind carry it away?

Here are some sources on terraforming Venus that might help answer your question, which is definitely intriguing.

This first paper mentions “heat pipes” which may be what you are looking for:

https://www.orionsarm.com/fm_store/TerraformingVenusQuickly.pdf

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268569275_Terraforming_Venus_A_Challenging_Project_for_Future_Colonization

https://science.howstuffworks.com/terraform.htm

https://www.academia.edu/4198039/Chapter_7_The_Terraforming_of_Venus

https://www.sciencealert.com/new-paper-explains-how-venus-hellscape-could-have-once-been-habitable

https://crowlspace.com/?p=1959

https://terraforming.fandom.com/wiki/Venus

http://www.worlddreambank.org/V/VENUS.HTM

https://www.inverse.com/science/venus-map-with-water

https://www.tor.com/2018/12/12/the-trouble-with-terraforming/

Thanks! I was thinking more of flexible hoses that suck the atmosphere out to space and allow the solar wind to sweep it away. Probably starting from the top and working down. I’m not sure if it would work and it would have to be modeled.

You can’t actually “suck” the atmosphere away: Space is already a vacuum, it’s doing as much “sucking” as is allowed by the laws of physics, over the entire planet. The problem is that there’s enough gravity to counter the suction.

You’d have to launch the atmosphere into orbit, as though it was a payload. Maybe a rotovator with scoops? Or orbital scoops in elliptical orbits? But however you do it, there’s a lot of energy involved in lifting that much mass.

You may be correct in that flow through an evacuated tube could not go any higher than the atmosphere. But it still could be pumped by force I think. That would then be equivalent to launching just as a space elevator to geostationary orbit is the equivalent of launching. It could be electrically driven and powered by solar energy. Thanks.

Besides, you want Venus hot, so as to use the heat for industrial purposes. Titan is good for plastics and hydrocarbons.

I wonder if Powell’s Airship to Orbit might be a good answer for Venus habs—just fly out to it pre-deployed.

A rigid airship can act as a rectenna, with ion wind propulsion in atmo’

I might want to extract some CO2 and acids and try to get CS (tear gas) as a working fluid. That is what you put in your heat pipes

Robert that is exactly what I have been thinking for years. If you can raise a crawler up a cable why not a pipe and siphon the dense atmosphere to space, though it may take a long time. Regardless of the technically proficient naysayers in the present (and we always need them to keep us straight), there is always the future and its long coattail of dreamers and miscreants who once in a while get it right. Watching a Falcon 9 booster return to the pad would have been science fiction to Neil and Buzz. We should/must dismiss the past when thinking about the impossible. I should/will get on the math of this by looking at the current state of affairs with the space elevator concept and the proposed mass of the crawler. We can easily estimate a flow rate if the pipe was a cable. The hard part will be determining the pipe part of the equation. In theory, a pipe of proper strength should be more stable and resilient under pressure than a simple cable, but will weigh much more and thus need to have a more massive and distant counter weight. I would suspect the show stopper could be the ultra-hypersonic flow of the 90 plus atmosphere of Venus burning the pipe to dust as soon as it turns on.

A pipe made of a few layers of graphene might fill the bill, but I think that the mass of atmosphere you are lifting makes this a non-starter.

KSM’s 2312 suggested turning the CO3 into a salt[?] so that it precipitated out was a solition to making Venus habitable.

If only one could transport the CO2 to Mars to make it warmer and thicken the atmosphere to 1 bar to make it far more habitable for humans…

Perhaps a skyhook that throws frozen CO2 in the direction of Mars?

One way is to blast it off, get enough deuterium from the outer solar system and then accelerate it using perhaps a Daedalus type probe. We need around I think 600 km/s at collision with Venus to cause a fusion reaction and I think around several billion tons of it. No mean feat I would believe. I suppose cooling towers at the poles could help as the atmosphere mass is the issue, turning over quick may do the trick. Either way a huge engineering task, but I do like the idea of floating cities though !

Once you get a proper siphon started the atmosphere could be jello and it still wouldn’t matter a hoot. The only show stopper is the raging flow rate said siphon creates.

The transportation of large volumes of gas from one planet to another might work by unfamiliar rules. Imagine you could accelerate a molecule of gas directly from the base of the exosphere of Venus so that its trajectory would take it to Mars. Conceptually you could do this with a much larger number of molecules from a wide area of Venus, creating a “beam” of gas which, in its rest frame, would initially be very cold – even if the molecules collided, they would adhere by virtue of being much below their freezing point. Sunlight would warm the gas over time, but even then, being at extremely low pressure, it might reach Mars before it could disperse too far. Now of course how to prepare each molecule for an interplanetary space mission is quite another question … but it seems somewhat related to laser cooling experiments. If there were two satellites in orbit around Venus, positioned to send just the right kinds of EM radiation through the exobase at one another, could they efficiently convert the solar energy they collect into providing molecules with a desired trajectory?

Billionaire boosts missions to the clouds of Venus.

New website at; https://venuscloudlife.com/

“MIT planetary scientist Sara Seager, one of the authors of the research paper published this week in Nature Astronomy, is leading the Breakthrough Initiatives’ project as principal investigator. There’s already a website devoted to the study, VenusCloudLife.com, and a virtual kickoff meeting is set for Sept. 18, she told me today.”

https://cosmiclog.com/2020/09/16/billionaire-boosts-missions-to-the-clouds-of-venus/

I found Landis’ 2003 paper “Colonization of Venus” at NTRS here:

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20030022668

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20030022668/downloads/20030022668.pdf

I also found this extensive article:

Will We Build Colonies That Float Over Venus Like Buckminster Fuller’s “Cloud Nine”?

By Robert Walker

January 12, 2014 at 07:02 AM

This idea dates back to the Russians in the early 1970s. The surface of Venus is far too hot, and the atmosphere too dense, for Earth life. However, our air is a lifting gas on Venus with about half the lifting power of helium on Earth. A habitat filled with normal air will float high in the dense Venus atmosphere, The atmospheric pressure there is the same as Earth sea level (1 bar). Temperatures are perfect for Earth life too, just over 0°C.

Also, just as weather balloons naturally rise to their operating level high in our atmosphere – so it works in the same way for our habitats on Venus. They float at a level where the pressure is equal inside and out, and can be of light construction. It is arguably the most hospitable region for humanity in our solar system, outside of Earth itself.

Venus cloud colony habitats can draw on our experience of buildings for the Earth surface, especially Buckminster fuller type lightweight domes. In this way, humans perhaps could colonize floating colonies just at the tops of the clouds of Venus. The surface of Venus is harsh in the extreme, way outside the range of habitability for any known form of Earth life. However, the environment at the cloud tops is surprisingly habitable.

Full article here:

https://www.science20.com/robert_inventor/will_we_build_colonies_that_float_over_venus_like_buckminster_fullers_cloud_nine-127573

If we do develop the technology to mine the near Earth asteroids it might pay to put a few in low orbits around Venus and mine them to build those

high-altitude colonies.

By the way, James Gunn’s short story can be found here: http://www.luminist.org/archives/SF/STA.htm.

The James Gunn “The Naked Sky” story is online:

https://archive.org/details/Startling_Stories_v33n03_1955-Fall

I like the idea of a manned balloon over Venus, but the highest a balloon can go on Earth is 23 miles and blimps or airships might have difficulty reaching 23 miles, but maybe they might with a little modification. The air pressure on Venus at that height is still five bars which is a problem. The airship would have to be able to go much higher which might be possible, for there still is a problem of the high wind speed and visibility as no balloon or air ship could go high enough to get above the cloud tops and haze into thin enough air to get a clear view of the cloud tops below as the one’s in the illustration in this article since the atmosphere of Venus is much thicker than Earths and the pressure is always greater in Venus atmosphere than Earth’s at the same altitude. Venus gravity is slightly less than Earth’s and an airship might fly a little higher, but I don’t think that is enough to get a clear view as the one’s in the illustration in this article. Venus gravity is slightly less than Earth’s and an airship might fly a little higher, but I don’t think that is enough. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atmosphere_of_Venus

I hope NASA can come up with a better Venus mission than just to test it’s atmosphere, but that is better than nothing. I was hopping for a well designed Venus orbiter and landing capsule with high resolution radar mapping capability, and all types of spectrometers, a passive radiometer, etc., but the lander must have spectrometers especially designed to probe the chemical composition of the rocks in the hostile surface conditions. Maybe we can have a joint mission with other countries contributing if that cost too much. There must be some way to drill into the rocks or ground or use a x ray spectrometer to determine their chemical composition.

I’m not clear why the 23 miles altitude is valid for Venus. On Earth, the air pressure at that altitude is about 0.04 bars. But if the pressure on Venus is 5 bars, isn’t there plenty of room to rise further until the airpressure in the lift vehicle reaches a level whether the lift is just sufficient to overcome the mass of the envelope and any payload?

As for the terrestrial altitude limit, J P Aerospace want to build a high altitude crewed station “Dark Sky” around 140,000 ft (about 26.5 miles altitude). I gather the record height is about 33 miles with just a gas-filled ballon. Theoretically, a rigid, but strong envelope, of zero mass, filled with a vacuum, could float on top of the atmosphere at LEO heights.

An interesting speculation of Venus gloating cities with numbers:

Will We Build Colonies That Float Over Venus Like Buckminster Fuller’s “Cloud Nine”?

An aerogel could do well here with a polymer coating.

Thanks Paul

I need to read all the papers, and like your other reading I liked your other post and this one.

A lot here to catch up on

Cheers Laintal

Hi Paul,

Sorry to side-track this wonderful discussion on an intriguing topic of immense interest, could you please, in one of your subsequent posts, also discuss about a recent paper titled “Planet discovered transiting a dead star” which was published in the latest print of Nature? It seems like a super interesting paper!

The link is here:

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02555-3?WT.ec_id=NATURE-20200917&utm_source=nature_etoc&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=20200917&sap-outbound-id=FD0AD71355740AC1ACF6C50FA4F0445B6C71632D

Interesting indeed, and yes, it’s already in queue for early next week.

I like Sci-Fi ideas about high altitude Venus colonization, but do not like the connection between H3P detection and colonization, on my opinion it totally unconnected issues, even more two this factors are extremely antagonistic.

If the H3P – is real biosignature, so there is native live in Venus clouds, in this case human colonization can cause Venus’s native life extinction, as we caused extinction of many live organisms on the Earth…

In dame time no life in higher atmospheric levels i.e. abiotic source fir H3P on the Venus does not mean impossibility of human colonization, opposite, no native life – means homo sapience cannot harm anything live – and this is the real good news…

The Limaye paper is a treasure trove, and its 2007 reference is also fascinating: http://lasp.colorado.edu/~espoclass/ASTR_5835_2015_Readings_Notes/Grinspoon%20&%20Bullock_Et_Al-EVTP.pdf The latter paper estimates the pH according to height, proposing a remarkably gentle value of 0.5 around 60 km, due to the accumulation of water in the upper acid droplets. They discuss a wide range of organisms capable of surviving those conditions … and worse. Apparently the Iron Mountain Superfund site in California, with acidic pyrite drainage pH -3.6, is far more acidic than Venus! [I’ll skip over the ‘G-plasma’ archaeans and snotites from H2S-rich caves with pH 0 to 1]

Now being written in 2007, Grinspoon et al. lamented that conditions below pH 0 were destroying their culture media. Since then, culture-independent DNA sequencing has taken off and so we see publications like https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4378227/ about the promisingly named Sulfobacillus acidophilus from the Iron Mountain site. The metabolic pathways of this organism seem adapted to more reducing conditions, but the overall concept from the Limaye paper of exchange of electrons between sulfur compounds and Fe2+/Fe3+ remains relevant. (We should expect this: iron-sulfur clusters exist even within our own cellular respiration, and iron was the main method of respiration for Earth life in the oceans right up until photosynthesis “poisoned” our atmosphere with oxygen)

Even if there is not life on Venus, thanks to the treasured biodiversity of our planet’s rich heritage of snotites and industrial pollution we might at least be able to put together a care package to get it started. [pending the issue of trace element requirements]

Excellent find. That there are organisms that can live at the acidic conditions believed to exist in the cloud zone certainly removes one constraint that seemed hard to overcome. It also makes Bain’s physical demonstations of the effect of concentrated sulfuric acid on organic matter in the BBC’s Sky at Night presentation rather irrelevant.

If Grinspoon et al are correct in their modeling then it seems plausible that microbial life could exist at that clement altitude. We’ll see how this shakes out. Oh, for a sample of that life if it exists!

Largest impact feature in the solar system is on Venus at over 8000 miles (13000 km) across.

http://www.largeigneousprovinces.org/sites/default/files/2011Feb-fig-1.png

This is the original article on Large Igneous Province (LIP) on Venus:

Artemis, the largest LIP on Venus—and perhaps in our Solar System.

Introduction

For Valentines Day 2011 it is a pleasure to present this month’s Large Igneous Province (LIP)—Artemis (named for the Greek goddess of the hunt) that forms a portion of Aphrodite Terra (named for the Greek goddess of love), on Earth’s sister planet, Venus—the Roman goddess of love. Venus’ Artemis forms a feature that is both spectacular and unique (perfect for any Valentine gift). Spectacular because Artemis’ signature extends over a 13000 km diameter area of Venus’ surface and its formation likely involved the planet’s core, mantle and lithosphere; and unique, because there is no similar feature recognized on Venus—or any other planet to date.

As historically defined Artemis includes an interior topographic high surrounded by Artemis Chasma (a 2100-km-diameter, 25–100-km wide, 1–2-km-deep nearly complete circular trough) and an outer rise (2400 km diameter) that transitions outward into the surrounding lowland. However, recent geologic mapping indicates that the traditional view of Artemis included only the center ‘seed pod’ of a much more expansive axisymmetric Artemis (Fig. 1), with an additional broad topographic trough (5000 km diameter) and suites of radial dikes and concentric wrinkle ridges extending in petal-like fashion away from the recognized center, with diameters of 12,000 and 13,000 km, respectively (Hansen & Olive 2010).

http://www.largeigneousprovinces.org/11feb

The hypothesis is that this is a large plume that has deformed Venus surface but if you look at: Ganymede: Largest Impact Crater in the Solar System? you’ll notice that the characteristics are very similar.

https://centauri-dreams.org/2020/08/20/ganymede-largest-impact-crater-in-the-solar-system/

Venus had a much thinner crust very similar to earth’s oceanic crust and probably at the time of impact was mostly covered by a deep ocean. The original impact was most likely destroyed and what we see now is the features that developed when the lithosphere, mantle and core rebounded from the super impact and after the new crust was forming.

Venus’ Ancient Layered, Folded Rocks Point to Volcanic Origin.

September 17, 2020. (Or maybe sedimentary rocks!)

“Tesserae are tectonically deformed regions on the surface of Venus that are often more elevated than the surrounding landscape. They comprise about 7% of the planet’s surface, and are always the oldest feature in their immediate surroundings, dating to about 750 million years old. In a new study appearing in Geology, the researchers show that a significant portion of the tesserae have striations consistent with layering.”

“While the data we have now point to volcanic origins for the tesserae, if we were one day able to sample them and find that they are sedimentary rocks, then they would have had to have formed when the climate was very different – perhaps even Earth-like.”

https://news.ncsu.edu/2020/09/venus-tesserae-volcanic/

SEPTEMBER 28, 2020 BY MATT WILLIAMS

Ancient Terrain on Venus Looks Like it Was Formed Through Volcanism.

In this respect, these research findings could be a step in the direction of resolving the debate of what caused Venus’ surface features: Oceans? Volcanoes? A little from column A, a little from column B?

https://www.universetoday.com/148000/ancient-terrain-on-venus-looks-like-it-was-formed-through-volcanism/#more-148000

Interesting article on a limit to the biomass possible of around 6 million tons to produce the observed results.

http://astrobiology.com/2020/09/on-the-biomass-required-to-produce-phosphine-detected-in-the-cloud-decks-of-venus.html

The notion that James Gunn had Venus pegged before we even entered the space age, made me curious whether he was (like some sf writers) a professional astronomer. Turns out he was a professional writer and English professor, among other pursuits. But thinking back to that era, when many Venus stories were set in Jurassic swamps, the closest description to the situation I can remember from a pop science writing astronomer was the suggestion that there might be boiling seas, but the seas would have soda water – so you would need a mixer. Like Giordano’s assertions about stars before telescopes and parallax measures, Gunn’s surmise before radio telescope soundings remains one for the records.

Still, along with the issue of dropping into a car battery if you lose anything over the rail of your dirigible ( no trash pickup, trash pickdown), there might be one consolation. If you can find a sailing region at 1 atmosphere or less and HZ temperate, the prevailing medium is CO2 with molecular weight of 44. Keep your windows shut. Now if you had molecular hydrogen (2) or monatomic helium (4)….

But that’s the whole problem.

The wind speed at one bar is 123 to 134 miles per hour at an altitude of 34 to 37 miles. An airship can go that high and an astronaut would be really riding the wind or gong fast. I would like to the see the exact physics of how they intend to pull off the inflation of the airship in the hurricane speed winds. Maybe it is inflated at a higher altitude without wind or in thinner, faster winds? The atmospheric pressure between 34 and 37 miles is only one bar to half a bar which is o.k. The lower cloud layer begins at 29 miles so the airship would be well inside the clouds with a limited visibility. The physics takes a little away from the romantic vision and a robot with a computer pilot might be safer than manned flight.

An manned airship or blimp above Mars might be safer and easier to make. It could be designed to drop to a lower altitude.

The raw wind speed doesn’t really tell us that much. If the entire atmosphere were to move as one, it would be no trouble. Now to be sure, there is turbulence – https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1982Icar…52..335W/abstract – the question is, how much turbulence, and can it be avoided?

At the other end, Earth is developing many clever carbon fibers and an appetite for renewed airship development. It seems most realistic that people would learn how to make luxury airships for long-term habitation here – hopefully with enough confidence in their integrity to be able to use hydrogen or at least methane in our atmosphere – before trusting lives to the system on Venus.

The clouds of Saturn await comparable development – but their winds are much faster than those of Venus!

Venus: science and politics

Even the discovery of a potential biosignature in the atmosphere of Venus cannot escape geopolitics. Ajey Lele discusses a claim made after the discovery by the head of Roscosmos that Venus is a “Russian planet.”

by Ajey Lele

Monday, September 21, 2020

https://www.thespacereview.com/article/4029/1

To quote:

There is a concept called Common Heritage of Mankind (CHM) introduced during the 1960s. This is an ethical concept and a general concept of international law. However, CHM does not have global acceptance. There is need to put CHM in the context of the solar system and interstellar space. It is important to argue that planets and other celestial bodies should belong to all humanity and an individual state or private agency should not own the resources over them.

Meet Calypso, a daredevil mission concept to explore the surface of Venus

By Paul Sutter a day ago

Just because it’s hard doesn’t mean we shouldn’t do it.

https://www.space.com/venus-calypso-surface-survey-idea.html

To quote:

Even nearly 40 years after the last Venera mission, we do not have the technology to build a reliable, long-term probe to survey the terrain of Venus like we do on Mars. What’s more, with all the interest in Mars exploration, including possible human visits, nobody really wants to spend the money on developing the technologies needed for a still-risky Venus venture.

But there could be another way to do it, and it’s called the Calypso Venus Scout, as outlined in a white paper recently posted to the preprint site arXiv.org. Calypso isn’t under NASA consideration right now; the paper’s author wrote about it to give the decadal survey, the government’s long-term planning process for planetary science, a broader sense of current options.

The mission tries to balance the twin challenges of Venus: The surface of Venus is just too dang hot, but orbital missions trying to study the surface are hampered by the miles and miles of thick, hazy cloud layers, making precise measurements incredibly difficult.

So Calypso would go in between.

Transfer of Life Between Earth and Venus with Planet-Grazing Asteroids.

September 21, 2020

http://astrobiology.com/2020/09/transfer-of-life-between-earth-and-venus-with-planet-grazing-asteroids.html

Transfer of Life Between Earth and Venus with Planet-Grazing Asteroids.

Amir Siraj, Abraham Loeb

Abstract.

Recently, phosphine was discovered in the atmosphere of Venus as a potential biosignature. This raises the question: if Venusian life exists, could it be related to terrestrial life? Based on the known rate of meteoroid impacts on Earth, we show that at least ?6×105 asteroids have grazed Earth’s atmosphere without being significantly heated and later impacted Venus, and a similar number have grazed Venus’s atmosphere and later impacted the Earth, both within a period of ?105 years during which microbes could survive in space. Although the abundance of terrestrial life in the upper atmosphere is unknown, these planet-grazing shepherds could have potentially been capable of transferring microbial life between the atmospheres of Earth and Venus. As a result, the origin of possible Venusian life may be fundamentally indistinguishable from that of terrestrial life.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.09512

There may be an easy way to tell if animal life was brought to Earth from Venus after the super impact ejected it. Asteroids and dust in orbit near Venus may have survived the 775 million years since the ocean world Venus was destroyed.

“Revealed!” –New Swarm of Asteroids Orbiting the Sun Alongside Venus.

Posted on Mar 13, 2019

“At first, it seemed likely that Venus’ dust ring formed like Earth’s, from dust produced elsewhere in the solar system. But when Goddard astrophysicist Petr Pokorny modeled dust spiraling toward the Sun from the asteroid belt, his simulations produced a ring that matched observations of Earth’s ring — but not Venus’.”

So they then explain how the square peg fits into the round hole!

The super impact fits!

(524522) 2002 VE68.

Provisional designation 2002 VE68, is a sub-kilometer sized asteroid and temporary quasi-satellite of Venus.[5] It was the first such object to be discovered around a major planet in the Solar System. In a frame of reference rotating with Venus, it appears to travel around it during one Venerean year but it actually orbits the Sun, not Venus.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/(524522)_2002_VE68

The population of Near Earth Asteroids in coorbital motion with Venus.

Abstract.

We estimate the size and orbital distributions of Near Earth Asteroids (NEAs) that are expected to be in the 1:1 mean motion resonance with

Venus in a steady state scenario. We predict that the number of such objects with absolute magnitudes H < 18 and H < 22 is 0.14 ± 0.03 and

3.5 ± 0.7, respectively. We also map the distribution in the sky of these Venus coorbital NEAs and we see that these objects, as the Earth coorbital NEAs studied in a previous paper, are more likely to be found by NEAs search programs that do not simply observe around opposition and that scan large areas of the sky.

https://www.oca.eu/images/LAGRANGE/pages_perso/morby/papers/MoraisVenus.pdf

“Revealed!” –New Swarm of Asteroids Orbiting the Sun Alongside Venus.

https://dailygalaxy.com/2019/03/revealed-new-swarm-of-asteroids-orbiting-the-sun-alongside-venus/

Co-orbital Asteroids as the Source of Venus’s Zodiacal Dust Ring.

Petr Pokorný1,2,3 and Marc Kuchner3

Published 2019 March 12 • © 2019. The American Astronomical Society

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ab0827/meta

Surprising Discovery Revealed After Sifting Through Solar System Dust.

https://scitechdaily.com/images/What-Scientists-Found-After-Sifting-Through-Dust-in-the-Solar-System.jpg

So these asteroids are what is left after the super impact and should hold the secret if advanced life on Earth came from Venus. Are we the descendants of Venus panspermia?

https://scitechdaily.com/surprising-discovery-revealed-after-sifting-through-solar-system-dust/

I suppose large cooling towers of 500 km in diameter reaching into the Venus sky’s at each pole could allow a turn over of the atmosphere. It’s easier to get rid of stored heat 50 km up than under a massive atmosphere.

Massive 800-million-year-old asteroid shower on Earth left dozens of huge craters on the moon.

“Around 800 million years ago, Earth was bombarded by meteorite fragments belonging to a huge, disintegrated 100-km-wide asteroid. The collective force of impact is believed to have been 30 to 60 times more than the Chicxulub impact — the asteroid that hit our planet off the coast of Mexico and wiped out the dinosaurs in one swift blow at the end of the Cretaceous.

However, you wouldn’t have any way of knowing this, as any crater older than 600 million years has been erased by the relentless grinding and sweeping of erosive forces. But the moon, which has such a minimal atmosphere it virtually doesn’t exist, still bears the pockmarks of this ancient onslaught that affected both Earth and its satellite.”

“Overall, 8 of 59 craters that the researchers examined were formed simultaneously. Based on crater scaling laws and collision probabilities, Terada and colleagues estimate that up to 5 trillion tones worth of meteoroids impacted the Earth-Moon system immediately before the Cryogenian (720-635 million years ago).”

”

Some of these fragments fell on Earth and the Moon, but also other terrestrial planets in the solar system, as well as the sun itself. Other fragments strayed into the asteroid belt, where they still roam today as part of the Eulalia family. Other remnants entered an orbital evolution as near-Earth asteroids, like Ryugu and Benny, which show rubble-pile structures. In 2018, JAXA landed two small rovers and a probe on the surface of Ryugu — marking an unprecedented feat.”

Snowball Earth and life thereafter.

After this massive meteorite shower bombed the Earth-Moon system, around 700 million years ago, the planet turned into a snowball. Virtually all of Earth’s surface became engulfed in polar ice sheets and the oceans turned to slush. Massive volcanic eruptions then spewed so much greenhouse gases into the atmosphere that Earth became so hot oceans were near their boiling point. Then, the ash-darkened skies triggered global cooling again, and Earth returned to its snowball form yet again.

It’s rather difficult to imagine a more inappropriate time for the tiny single-celled and multicellular organisms that came into existence. But oddly enough, this difficult geological period, known as the Cryogenian, coincides with the moment complex animal life evolved. Out of the alternating ice and inferno sprang the first complex creatures that would eventually evolve into jellyfish and corals, snails, fish, dinosaurs, birds, and, at some point, humans.

Where do these 800-million-year-old impacts fit into all of this? The study suggests that the meteorites deposited 100 billion tonnes of phosphorus on Earth, “which is one order of magnitude higher than the total phosphorus amount of the modern sea (assuming that the volume of modern seas is 13.5×10^8 km3 and the concentration of P is approximately 3 ?g/litre),” Terada told ZME Science.

“Interestingly, Reinhard et al. (Nature 2017) found that the average P content of late Tonian samples is more than four times greater than that of pre-Cryogenian samples and noted that a fundamental shift in the phosphorus cycle may have occurred during the late Proterozoic Eon after 800 Ma (until 635 Ma),” the Japanese researcher added.

https://www.zmescience.com/space/800-million-year-old-meteorite-shower-moon-craters-0423423/

Venus super impact.

Meteorites deposited 100 billion tonnes of phosphorus on Earth.

Asteroid shower on the Earth-Moon system 800 million years ago revealed by lunar craters.

https://phys.org/news/2020-07-asteroid-shower-earth-moon-million-years.html

There is a lot more to the story!

Lunar Exploration as a Probe of Ancient Venus.

[Submitted on 5 Oct 2020]

Samuel H. C. Cabot, Gregory Laughlin

“An ancient Venusian rock could constrain that planet’s history, and reveal the past existence of oceans. Such samples may persist on the Moon, which lacks an atmosphere and significant geological activity. We demonstrate that if Venus’ atmosphere was at any point thin and similar to Earth’s, then asteroid impacts transferred potentially detectable amounts of Venusian surface material to the Lunar regolith. Venus experiences an enhanced flux relative to Earth of asteroid collisions that eject lightly-shocked (?40 GPa) surface material. Initial launch conditions plus close-encounters and resonances with Venus evolve ejecta trajectories into Earth-crossing orbits. Using analytic models for crater ejecta and \textit{N}-body simulations, we find more than 0.07% of the ejecta lands on the Moon. The Lunar regolith will contain up to 0.2 ppm Venusian material if Venus lost its water in the last 3.5 Gyr. If water was lost more than 4 Gyr ago, 0.3 ppm of the deep megaregolith is of Venusian origin. About half of collisions between ejecta and the Moon occur at ?6 km s?1, which hydrodynamical simulations have indicated is sufficient to avoid significant shock alteration. Therefore, recovery and isotopic analyses of Venusian surface samples would determine with high confidence both whether and when Venus harbored liquid oceans and/or a lower-mass atmosphere. Tests on brecciated clasts in existing Lunar samples from Apollo missions may provide an immediate resolution. Alternatively, regolith characterization by upcoming Lunar missions may provide answers to these fundamental questions surrounding Venus’ evolution.”

https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.02215

Now we are getting somewhere! ;-}

Did a migrating Jupiter turn Venus into hell?

By Paul Sutter 8 hours ago

The giant planet’s long-ago migration likely had big impacts.

https://www.space.com/migrating-jupiter-turn-venus-into-hell

A theory from 2006 may explain the reason Venus surface has been resurfaced in the las 800 million years and why also its rotation rate is backwards (clockwise as seen from above its north pole, rather than counterclockwise, as it is for Earth and the other planets).

“Alex Alemi, at the California Institute of Technology, and Caltech planetary scientist David Stevenson suggested that Venus underwent not one but two large impacts. The first hit on the side of Venus that caused the planet to spin counterclockwise. It created a moon that began to drift away, like Earth’s. The second slammed into the side of Venus that caused it to spin clockwise–canceling the effect of the first collision. The cancellation need not have been exact; the sun’s gravity could have completed the task of slowing and even reversing Venus’s rotation. The reversal changed the gravitational interactions between the moon and planet, causing the moon to start moving inward and ultimately collide with the planet. The second impact may or may not have created a moon, too. If it did, this moon would have been swept up by the first one on its inward plunge toward doom.”

“Stevenson says that this model can eventually be tested by looking at isotopic signatures in Venusian rocks.”

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/double-impact-may-explain/

Interesting Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD) video of why every time Venus passes the Earth, it shows the same face to us!

https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap200603.html

Explanation: Every time Venus passes the Earth, it shows the same face. This remarkable fact has been known for only about 50 years, ever since radio telescopes have been able to peer beneath Venus’ thick clouds and track its slowly rotating surface. This inferior conjunction — when Venus and Earth are the closest — occurs today. The featured animation shows the positions of the Sun, Venus and Earth between 2010-2023 based on NASA-downloaded data, while a mock yellow ‘arm’ has been fixed to the ground on Venus to indicate rotation. The reason for this unusual 1.6-year resonance is the gravitational influence that Earth has on Venus, which surprisingly dominates the Sun’s tidal effect. If Venus could be seen through the Sun’s glare today, it would show just a very slight sliver of a crescent.

Assuming Earth’s gravitational influence has that effect on Venus, and Venus is such a near mass equivalent of Earth, it begs the question: What’s the gravitational effect of Venus on Earth? Or the Moon for that matter?

OCTOBER 7, 2020

Looking for pieces of Venus? Try the Moon

by Yale University

A growing body of research suggests the planet Venus may have had an Earth-like environment billions of years ago, with water and a thin atmosphere.

Yet testing such theories is difficult without geological samples to examine. The solution, according to Yale astronomers Samuel Cabot and Gregory Laughlin, may be closer than anyone realized.

Cabot and Laughlin say pieces of Venus—perhaps billions of them—are likely to have crashed on the moon. A new study explaining the theory has been accepted by the Planetary Science Journal.

The researchers said asteroids and comets slamming into Venus may have dislodged as many as 10 billion rocks and sent them into an orbit that intersected with Earth and Earth’s moon. “Some of these rocks will eventually land on the moon as Venusian meteorites,” said Cabot, a Yale graduate student and lead author of the study.

Cabot said catastrophic impacts such as these only happen every hundred million years or so—and occurred more frequently billions of years ago.

“The moon offers safe keeping for these ancient rocks,” Cabot said. “Anything from Venus that landed on Earth is probably buried very deep, due to geological activity. These rocks would be much better preserved on the moon.”

Many scientists believe that Venus might have had an Earth-like atmosphere as recently as 700 million years ago. After that, Venus experienced a runaway greenhouse effect and developed its current climate. The Venusian atmosphere is so thick today that no rocks could possibly escape after an impact with an asteroid or comet, Cabot said.

Laughlin and Cabot cited two factors supporting their theory. The first is that asteroids hitting Venus are usually going faster than those that hit Earth, launching even more material. The second is that a huge fraction of the ejected material from Venus would have come close to Earth and the moon.

“There is a commensurability between the orbits of Venus and Earth that provides a ready route for rocks blasted off Venus to travel to Earth’s vicinity,” said Laughlin, who is professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Yale. “The moon’s gravity then aids in sweeping up some of these Venusian arrivals.”

Full article here:

https://phys.org/news/2020-10-pieces-venus-moon.html

The paper is online here:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.02215

Surprising Insights Into the Asteroid Bennu’s Past, as OSIRIS-REx Prepares For a Sample-Collecting.

Could Asteroid Bennu be a rubble pile of material left over from the super impact 700 to 800 million years ago that destroyed Venus?

https://manyworlds.space/2020/10/08/surprising-insights-into-the-asteroid-bennus-past-as-osiris-rex-prepares-for-a-sample-collecting-tag/

https://i0.wp.com/manyworlds.space/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Screen-Shot-2020-10-07-at-6.27.52-PM.jpeg?w=1323&ssl=1

Viens in a Bennu boulder tell of running water on the asteroid’s parent body long, long ago. In the center are PolyCam images with the vein marked with a circle The same images on right have be photometrically corrected. The circled vein is ~8 cm wide and 52.5 cm long. (NASA)

Asteroid shower on the Earth-Moon system 800 million years ago revealed by lunar craters.

Some of the resulting fragments fell on terrestrial planets. Others stayed in an asteroid belt as the Eulalia family, and remnants had orbital evolution as a member of near-Earth asteroids.

Simulations suggest that Bennu has a 70% chance it came from the Polana family and a 30% chance it derived from the Eulalia family.

The Romantic Venus We Never Knew

Venus used to be as fit for life as Earth.

BY DAVID GRINSPOON

DECEMBER 8, 2016

http://nautil.us/issue/43/heroes/the-romantic-venus-we-never-knew

Is Venus a living hell? Conversation with astrobiologist David Grinspoon

by Leonard David — October 12, 2020

Over the years, space missions to hellish Venus have been few and far between. But the idea of intensely studying that nearby cloud-veiled globe has just received a renewed lease on life, quite literally.

A global team of researchers using ground-based observatories announced Sept. 14 the detection of phosphine gas wafting about in the clouds of Venus. On Earth, this gas is only made in significant quantities industrially — or by microbes that thrive in oxygen-free environments. The detection has given rise to the thought of extraterrestrial “aerial” life on hostile Venus.

This promising find begs the question: Now what?

SpaceNews contributor Leonard David discussed this issue with astrobiologist David Grinspoon, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute and an expert on surface-atmospheric interactions on terrestrial planets, such as Venus.

Full interview here:

https://spacenews.com/is-venus-a-living-hell-conversation-with-astrobiologist-david-grinspoon/

To quote:

You have been an advocate of cloud life at Venus since the 1990s. Are you heartened that others are now in pursuit of this viewpoint?

I have always been the guy at the conference in the Venus session giving that last talk about the possible life in the clouds. And people would roll their eyes. They kind of tolerated it because of my other work about the clouds, the surface and Venus’ atmosphere. The life idea I have been pushing was not really embraced. But recently it has been more embraced, not with the phosphine finding. It is because our models have been changing in the last few years.

It looks much more like Venus may have had a long habitable epoch on its surface, maybe billions of years of oceans. Then it should have had a biosphere. Therefore, you have to ask what happened to that biosphere when the surface went bad?

But I’m also wary of having life-friendly clouds as the only reason we’re interested in Venus. It needs to be broader than just the life question.

For instance, the exoplanet community is going to be finding a lot of planets in the Venus zone. They need ground-truth and want us to send missions to Venus. It will help them understand what is now a trickle, but will soon become a fire hose of information about terrestrial planets in the galaxy.

How OHB intends to bring scientific instruments into the atmosphere of Venus

DOES LIFE EXIST ON OUR EARTH’S CLOSEST NEIGHBOUR?

https://www.ohb.de/en/magazine/destination-venus-part-7-how-ohb-intends-to-bring-scientific-instruments-into-the-atmosphere-of-venus

Did Pioneer Venus detect phosphine in 1978?

https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/did-pioneer-venus-find-phosphine-first/

What about the Soviet Venera probes, especially the Vega missions of 1985?

Is Venus a living hell? Conversation with astrobiologist David Grinspoon

by Leonard David — October 12, 2020

Over the years, space missions to hellish Venus have been few and far between. But the idea of intensely studying that nearby cloud-veiled globe has just received a renewed lease on life, quite literally.

A global team of researchers using ground-based observatories announced Sept. 14 the detection of phosphine gas wafting about in the clouds of Venus. On Earth, this gas is only made in significant quantities industrially — or by microbes that thrive in oxygen-free environments. The detection has given rise to the thought of extraterrestrial “aerial” life on hostile Venus.

This promising find begs the question: Now what?

SpaceNews contributor Leonard David discussed this issue with astrobiologist David Grinspoon, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute and an expert on surface-atmospheric interactions on terrestrial planets, such as Venus.

https://spacenews.com/is-venus-a-living-hell-conversation-with-astrobiologist-david-grinspoon/