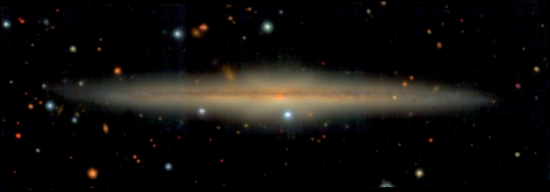

The galaxy UGC 10738 resonates with the galaxy described yesterday — BRI 1335-0417 — in that it raises questions about how spiral galaxies form. In fact, the team working on UGC 10738 thinks it goes a long way toward answering them. That’s because what we see here is a cross-sectional view of a galaxy much like the Milky Way, one that has both ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ disks like ours. The implication is that these structures are not the result of collisions with smaller galaxies but typical formation patterns for all spirals.

Nicholas Scott and Jesse van de Sande (ASTRO 3D/University of Sydney) led the study, which used data from the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. As you can see from the image below, the galaxy, some 320 million light years away, presents itself to us edge on, offering a cross-section of its structure. Key to the work was the team’s assessment of stellar metallicity, as van de Sande explains:

“Using an instrument called the multi-unit spectroscopic explorer, or MUSE, we were able to assess the metal ratios of the stars in its thick and thin discs. They were pretty much the same as those in the Milky Way – ancient stars in the thick disc, younger stars in the thin one. We’re looking at some other galaxies to make sure, but that’s pretty strong evidence that the two galaxies evolved in the same way.”

Image: Galaxy UGC 10738, seen edge-on through the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, revealing distinct thick and thin discs. Credit: Jesse van de Sande/European Southern Observatory.

Published in Astrophysical Journal Letters, the study argues that the thin and thick disks found in the Milky Way — and the similar structures found in UGC 10738 — indicate that rather than being the result of chance collisions with other galaxies, the different disks reveal a standard path of galaxy formation and evolution. They would be unlikely to be repeated elsewhere if the result of a rare and violent merger.

The ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ disks are interesting features, with the former primarily made up of ancient stars that show a low ratio of iron to hydrogen and helium. Tracing the metallicity of the thin disk stars reveals that they are younger and contain more metals. Our Sun is a thin disk star, and as the authors note, it is made up of about 1.5% elements heavier than helium (the definition of ‘metals’ in astronomical parlance). Stars of the thick disk show three to ten times less metal content, a striking difference.

Finding the same differences in the two disk structures in other spiral galaxies points to the likelihood that the Milky Way formed in a way common to such galaxies. Says Scott:

“It was thought that the Milky Way’s thin and thick discs formed after a rare violent merger, and so probably wouldn’t be found in other spiral galaxies. Our research shows that’s probably wrong, and it evolved ‘naturally’ without catastrophic interventions. This means Milky Way-type galaxies are probably very common. It also means we can use existing very detailed observations of the Milky Way as tools to better analyse much more distant galaxies which, for obvious reasons, we can’t see as well.”

So we have what the authors describe as a ‘tension’ between two formation scenarios, one stochastic, one common to spiral galaxies. But let’s get into the weeds a little. The paper goes on to widen the sample into other subtypes of galaxy:

This tension is further enhanced once early-type disk galaxies with [α/Fe]-enhanced thick disks are included in the population of present day galaxies with similar formation histories (Pinna et al. 2019b; Poci et al. 2019, 2021). That early-type disk galaxies are found to contain similar abundance patterns as found in the Milky Way (i.e. increased mean [α/Fe] off the plane of the disk) is unsurprising. Such galaxies represent one plausible end point for the Milky Way’s evolutionary history, suggesting a shared and generic evolutionary pathway for disk galaxies.

All of this harks back to Edwin Hubble’s classification of galaxies (the Hubble Sequence). The phrase “early-type” galaxies” refers to elliptical and lenticular galaxies, as opposed to spiral and irregular galaxies, without implying an evolutionary path from one type to another. So the authors are speculating when they talk about an ‘evolutionary end point’ for the Milky Way, but it’s an interesting speculation:

The Milky Way is often identified as a so-called ‘green valley’ galaxy (Mutch et al. 2011), a galaxy already undergoing a transition to the red sequence. When fully quenched (and assuming no dramatic structural changes in the mean time) the Milky Way will likely resemble a lenticular galaxy similar to FCC 170 (Pinna et al. 2019a).

The ‘green valley’ refers to galaxies where star formation has been slowed, either because they have exhausted their reservoirs of gas, or (in younger galaxies) have undergone mergers with other galaxies. Both the Milky Way and Andromeda are assumed to be green valley galaxies of the first kind.

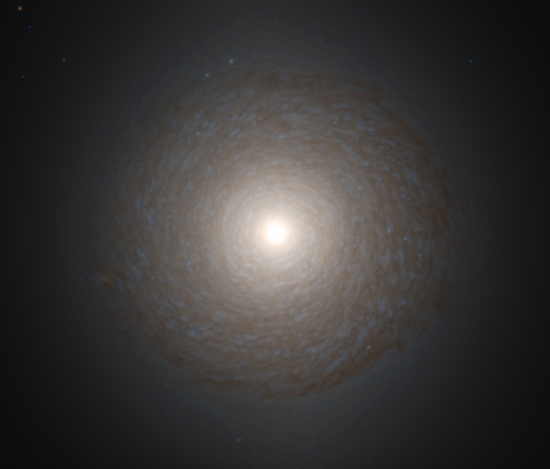

FCC 170 (NGC 1381) is a lenticular galaxy found in the constellation Fornax, about 60 million light years from Earth, a member of the Fornax Cluster (hence the FCC designation, standing for Fornax Cluster Catalogue). As a lenticular, it is in a middle stage between a spiral and an elliptical galaxy, with a large scale disk but lacking spiral arms on the scale of a true spiral galaxy. Is this the Milky Way’s future?

And then, of course, there is the merger with Andromeda to look forward to. How much we have to learn about how galaxies change over time!

Image: This is NGC 1387, a lenticular galaxy likewise in the Fornax Cluster, and better angled to show the lack of spiral structure in such galaxies than FCC 170. Credit: Fabian RRRR. Based on observations made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, and obtained from the Hubble Legacy Archive, which is a collaboration between the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI/NASA), the Space Telescope European Coordinating Facility (ST-ECF/ESA) and the Canadian Astronomy Data Centre (CADC/NRC/CSA). CC BY-SA 3.0.

The paper is Scott et al., “Identification of an [α/Fe]—Enhanced Thick Disk Component in an Edge-on Milky Way Analog,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 913, No. 1 (24 May 2021), L11 (abstract / preprint).

Is Barnard’s Star a thick disk star? It is fast (‘runaway”) and has low metallicity.

From Wikipedia:

Barnard’s Star has 10–32% of the solar metallicity.[3] Metallicity is the proportion of stellar mass made up of elements heavier than helium and helps classify stars relative to the galactic population. Barnard’s Star seems to be typical of the old, red dwarf population II stars, yet these are also generally metal-poor halo stars. While sub-solar, Barnard’s Star’s metallicity is higher than that of a halo star and is in keeping with the low end of the metal-rich disk star range; this, plus its high space motion, have led to the designation “intermediate population II star”, between a halo and disk star.[3][22] Although some recently published scientific papers have given much higher estimates for the metallicity of the star, very close to the Sun’s level, between 75 and 125% of the solar metallicity.[26][27]

Is Intermediate Population II “thick disk”?

“This means Milky Way-type galaxies are probably very common.”

The quoted sentence was a surprise to me. I don’t believe there is any need for the qualifier “probably”. There is a lot of statistical data on galaxy classification, most recently as a result of the Galaxy Zoo project. Am I seeing the sentence outside of its context?

I agree with this paper. If the disks are thicker because they are older, then all thicker disk galaxies are the result of mergers of two galaxies with thinner disks which means that a lenticular galaxy is the future of our galaxy and elliptical galaxies are the final stage of the evolution of galaxies made by the most mergers which would explain why they have the most stars.

If we think about density waves in the spiral arms of galaxies like water waves on the surface of water after a rock is thrown into the water, then it makes sense that the lenticular galaxies in the photo in this article would look different than the arms of a spiral galaxy, so we have a disruption of the spiral arms from more density waves caused by collision and merger with another galaxy.

My guess is that spiral arms are formed when the orbits of stars are coupled (an alignment of their semi-major axes); they interact with one another and density waves result. The waves race along the disk, at a constant speed, but the spiral pattern forms because at greater radii they have further to travel, they lag behind and can’t keep up. Remember, the star density, or the interstellar medium (ISM), is no different in the arms than it is in the spaces between the arms. What we are seeing is a compression wave that circles the galaxy and when it passes it compresses the interstellar medium causing new stars to “precipitate” from the ISM. The stars that are already there, or the new ones formed by the compression wave, are not affected by the passing wave, they aren’t dragged along with it. But some of these new stars are massive young giants, so bright they mark the passage of the wave long after its gone. These bright new giants evolve rapidly and quickly burn out, we don’t see them in the inter-arm gaps. Its analogous to the whitecaps, foam and spindrift that mark the crests of big seas in an ocean storm, they also survive for a brief while after the wave crest passes.

In other words, spiral structure is a consequence of the dynamical behavior of the galaxy, a collision with another galaxy would tend to disrupt this process, destroying the spiral pattern and leaving an elliptical or lenticular galaxy. This would tend to explain why the proportion of elliptical systems is so high in the centers of large clusters of galaxies where these collisions are more frequent.

In galactic collisions, the systems pass through each other and there are few, if any, stellar encounters. But the molecular clouds in the ISM violently interact and the orbits of individual stars perturb one another.

The density waves are disrupted and the spiral arms are disturbed.

Reading this article should remind us of how much remains to be learned in astronomy. Even the most basic anatomy of the Milky Way is just being worked out here, thanks to a precisely edge-on galaxy with similar characteristics to compare to. Even the most basic physics of the Milky Way – the tendency of everything to orbit at the same rate like a phonograph record instead of a Solar System – can only be answered with a mumble about “dark matter” of unknown characteristics. The sequence of formation of galaxies, and their fate, remains more hypothesis than theory.

This basic research, which can tell us so much, may have very useful applications. Galaxy shape and formation is what told us dark matter existed – a substance that makes up most of the universe and we know nothing about. If hot dark matter passes through us at relativistic velocities at every moment, imagine the unlimited energy that we could tap into if we could find a way to interact with it. Imagine the unlimited, practically “reactionless” propulsion we could have if we could interact with only dark matter moving in a specific direction. That is even before the physicists draw any other potential conclusions from such results. Carry on!

Thankyou for posting the details of the density wave in galaxies, Henry Cordova. It’s been a while since I read about it. It’s in the book 100 Billion Suns which is 1983, so it is interesting that that idea been around for a while, i.e., the principles of physics are still and always valid.

If I remember correctly, the density wave catches up with the gas and compresses it which starts the star formation. The position of the stars which take time to form through gravitational collapse is different than when there were in the density wave so the stars end up being behind the density wave. Wikipedia, Density wave theory and Kippenhahn 1983, ibid. My analogy with the stone in the pond should not be taken literally, of course as I meant to illustrate a wave or ripple on water is like the density waves in a galaxy. I read that somewhere online and I can’t remember the reference to site it.

Wikipedia has an excellent article on the subject, along with some wonderful diagrams and animations that make it all very clear.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Density_wave_theory