An interstellar freebie like ‘Oumuamua or 2I/Borisov is priceless. We don’t need to travel light years to see it because it comes to us. Although we’re expecting to find a lot more such objects as instruments like the Vera Rubin Observatory come online, right now only two are known to have passed through our system. But only slightly less inaccessible places like the Oort Cloud also bring gifts in the form of long-period comets, and I don’t want the advent of C/2014 UN271 Bernardinelli-Bernstein to go unnoticed in these pages, given its startling size and already detected activity.

Pedro Bernardinelli (University of Pennsylvania), who along with colleague Gary Bernstein discovered the comet, estimates its nucleus as being between 100 and 200 kilometers (62 and 125 miles) long. This dwarfs Hale-Bopp, and Colin Snodgrass (University of Edinburgh) is quoted in the New York Times as saying: “With a reasonable degree of certainty, it’s the biggest comet that we’ve ever seen.”

The discovery involved reprocessing data from the Dark Energy Survey, data that had been acquired via the 4-meter Blanco instrument at Cerro Tololo in Chile between 2013 and 2019. Bernardinelli and Bernstein announced the find in June of this year.

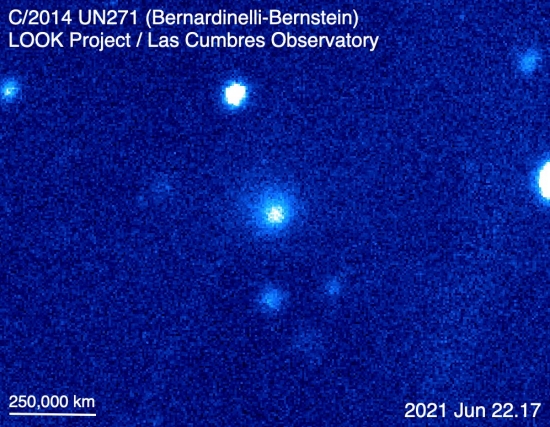

C/2014 UN271 was at roughly the distance of Neptune when first acquired in the data, although it is now about 20 AU out, or twice the distance of Saturn. While there was no statement about activity on the comet when the discovery was announced, astronomers at Las Cumbres Observatory quickly turned their network of telescopes on the object.

Las Cumbres offers a globally distributed network of telescopes with 24-hour robotic operation that is finely tuned to detect transients. Its instruments have now revealed that C/2014 UN271 is active, with the 1-meter LCO telescope at the South African Astronomical Observatory returning images that, in keeping with the international flavor of the observing effort, drew the attention of astronomers in New Zealand.

Thus Michele Bannister (New Zealand’s University of Canterbury):

“Since we’re a team based all around the world, it just happened that it was my afternoon, while the other folks were asleep. The first image had the comet obscured by a satellite streak and my heart sank. But then the others were clear enough and gosh: there it was, definitely a beautiful little fuzzy dot, not at all crisp like its neighbouring stars!”

Comet C/2014 UN271 was indeed active, that fuzzy dot indicating a coma. Volatile ices, likely carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, were already reacting to the scant sunlight available. The coma was active even with the comet almost three billion kilometers from the Sun. No comet has ever been observed to be active this far from Sol.

Image: Comet C/2014 UN271 (Bernardinelli-Bernstein), as seen in a synthetic color composite image made with the Las Cumbres Observatory 1-meter telescope at Sutherland, South Africa, on 22 June 2021. The diffuse cloud is the comet’s coma. Credit: LOOK/LCO.

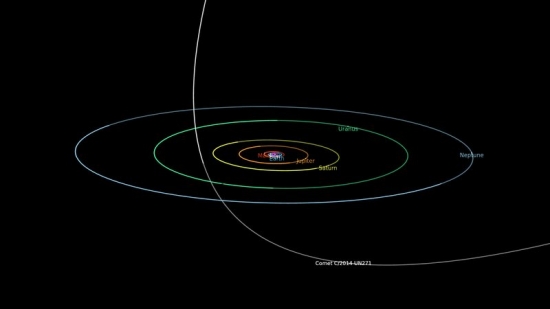

This is one useful object, particularly since it was discovered early in its entry into the realm of the planets. It should offer astronomers over a decade of observing time. Perihelion is not expected until 2031, although when it comes, the comet will still be well beyond Saturn. Its orbit is now projected to take three million years to complete.

Image: An orbital diagram showing the path of Comet C/2014 UN271 (Bernardinelli-Bernstein) through the Solar System. The comets’ path is shown in gray when it is below the plane of the planets and in bold white when it is above the plane. Credit: NASA.

The discovery of activity on C/2014 UN271 draws attention to the LOOK Project now active at Las Cumbres. LOOK stands for LCO Outbursting Objects Key, an effort that investigates unexpected brightening of comets through burst activity and other aspects of comet evolution. Out of all this we should get a better understanding of comet outbursts, of which C/2014 UN271 is offering such a tantalizing sample.

These findings should also feed into future space missions like the European Space Agency’s Comet Interceptor, using data from this and other wide field surveys. Las Cumbres staff scientist Tim Lister explains:

“There are now a large number of surveys, such as the Zwicky Transient Facility and the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory, that are monitoring parts of the sky every night. These surveys can provide alerts if one of the comets changes brightness suddenly and then we can trigger the robotic telescopes of LCO to get us more detailed data and a longer look at the changing comet while the survey moves onto other areas of the sky. The robotic telescopes and sophisticated software of LCO allow us to get images of a new event within 15 minutes of an alert. This lets us really study these outbursts as they evolve.”

That’s good news for the next interstellar object that wanders by as well. One of these days our growing network of instruments will be able to spot something like ‘Oumuamua in time for a spacecraft to pay it a visit.

A rendezvous of some kind, someday – perhaps even with a Rama?

Hi Paul & readers

Yes this is one interesting comet to follow, It would be nice to meet with Michele Bannister sometime too, she missed the conference last weekend.

I’m sure there will be lots more on this one to watch out for in the news

Cheers Edwin

I would love to see a 200 km comet diving into the solar corona as a sun-grazer. Immagine the explosive amount of activity we could see in our skies for months as billions of kg of ice are sublimated. A tail like that would cross the entire ineer solar system. And immagine the massive meteor showers we would get for thousands of years after that.

That happen not to long ago, about 12800 years ago of which we see the remnants of in the Taurid meteor shower today. Possibly causing the great flood that many ancient civilizations have myths about.

A comet impact may have paved the way for human civilization.

“The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis argues that a comet strike caused major changes to climate and human cultures on Earth about 13,000 years ago.”

https://bigthink.com/surprising-science/younger-dryas-impact

Very interesting Michael.

But IMO, this is not comparable at all.

The estimated size of the Younger Dryas impactor is 4 km. That is 50 times smaller than this new comet. In terms of mass, which is like saying energy release (asuming similar shape, density and velocity), the comet could be 125000 times more massive.

Even if you compare It with the Chixhulub impactor (considered to be around 15 km in diamter), which wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs, an impact of an object like 2014 UN271 would be 2370 times more devastating!

A comet the size of Mimas would probably be able to eradicate all complex life from Earth.

Anyway, I wasn’t talking about an impact scenario, wich is extremely improbable, but about a comet like this getting as close to the Sun as Halley or even closer. That would be a fantastic display of fireworks in the inner Solar System. Just again, immagine the meteor showers we would get with something like that.

An other quite disturbing thought here is that we just discovered a new member of a select group of observable Oort cloud members. Considering its size as a object, the size of the sample and that the Oort cloud is estimated to have trillions of comets this means that there probably many objects of this size. And if the Oort cloud population follows a mass power-law (like the asteroid belt does), this means that there can be larger comets.

Will we find Moon sized comets? Or even Earth size comets? That is terrifying to think about.

The original comet came in from a long period and was transferred to a short period Jovian family. It was very large and broke into smaller pieces after many close encounters to the sun. There was not just one impact but many and over a long period of time. The majority where in the oceans with little if any record left of their impacts except for the huge tsunami. These impacts go back a 10 of thousands of years and may be why so many of the stone age megaliths are related to astronomical alignments. The original ancient Antediluvian civilization in Sundaland was flooded by the impacts and the melting ice age and and they dispersed around the world.

https://atlantisjavasea.files.wordpress.com/2020/12/younger-dryas-dispersal.png

https://atlantisjavasea.com/2015/09/29/sundaland/

Look up Clube, Napier, Sweatman. They hypothesize that a comet similar in size to this one entered the inner Solar System a few 10k years ago, disintegrated and created the “zodiacal light”, comet Enke (merely a remnant), the Taurid meteor stream, and several impactors that kicked off the Younger Dryas cooling. The evidence is mounting.

I wonder if its orbit can place more restrictions on the possible planet X.

Couple of questions based on teh Wikipedia entry:

1. The inbound (40,000 AU) and outbound (54,000 AU) aphelions are different. Does this mean that the comet has been given a gravitational kick after perihelion?

2. Size. There seems to be some dispute about the size, suggestion that it may be much smaller that stated in the eOP, perhaps no bigger than Hale-Bopp (diameter 60 +/- 20 km)

I do see variation in size depending on which source you look at, though I haven’t run into any mention of it being no bigger than Hale-Bopp. Don’t know the answer to the first question, I’m afraid.

I don’t the answer to the first question also. I’ll Google it. According to Nasa, interstellar object 1I/2017 U1 has a faster speed on the way out 89,000 than it’s cruising speed through interstellar space. It will eventually end up with the same cruising speed of 59.000 when it exits the solar system so the gravity of the Sun takes time to slow it down. It’s top speed was 196,000 miles per hour. We can use it as a model for the interstellar comet. https://www.nasa.gov/planetarydefense/faq/interstellar The speed of the orbit changes based on it’s distance from the Sun based on Kepler’s third law and Newtons law of universal gravitation.

I could be wrong, but a comet this large (the comet is 2E+2/1.4E+9 radians = 0.06 arc sec I think, but we can use the much larger radius of the Earth and some of the orbital distance the Earth sweeps in a day, plus some satellite orbits, I think) seems bound to eclipse quite a number of stars on its journey. Is there a plan afoot to observe these eclipses, determine the duration of each from several vantages to develop a high-resolution model of the comet’s shape, and measure the absorption frequencies of its “atmosphere” to maybe find some interesting organic chemicals?

There is yes, check out the Comets-ml Group: https://groups.io/g/comets-ml/topics