Anomalies in our models are productive. Often they can be explained by errors in analysis or sometimes systematic issues with equipment. In any case, they force us to examine assumptions and suggest hypotheses to explain them, as in the case of the unusual acceleration of stars that has turned up in two areas. Greg Matloff has written about one of them in these pages, the so-called Parenago’s Discontinuity that flags an unusual fact about stellar motion: Cool stars, including the Sun, revolve around galactic center faster than hotter ones.

This shift in star velocities occurs around (B-V) = 0.62, which corresponds to late F- or early G-class stars and extends down to M-dwarfs. In other words, stars with (B-V) greater than 0.61 revolve faster. The (B-V) statement refers to a color index that is used to quantify the colors of stars using two filters. One, the blue (B) filter, lets only a narrow range of wavelengths centered on blue colors through, while the (V) visual filter only passes wavelengths close to the green-yellow band. Hot stars have (B-V) indices closer to 0 (or negative); cool M-dwarf stars come out closer to 2.0. Proxima Centauri’s (B-V) number, for example, is 1.90. The (B–V) index for the Sun is about 0.65.

What the Soviet space scientist Pavel Parenago (1906-1960) had observed is that cooler stars, at least in the Sun’s neighborhood, revolve about 20 kilometers per second faster around the galactic center than hotter, more massive stars. Work in the 1990s using Hipparcos data on over 5,000 nearby main sequence stars clearly showed the discontinuity. An early question was whether or not this was an effect local to the Sun, or one that would prove common throughout the galaxy.

Image: Soviet space scientist Pavel Parenago. Credit: Visuotin? Lietuvi?.

The answer came in the form of a paper by Veniamin Vityazev (St. Petersburg State University) and colleagues in 2018. The scientists hugely expanded the stars in their sample by using the Gaia Data Release 1 dataset,. The Gaia release included some 1,260,000 stars on the main sequence and a further 500,000 red giants. As we saw yesterday, the Gaia mission, which launched in 2013, is continuing to gather data at the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point, using astrometric methods to determine the positions and motions of a billion stars in the galaxy.

You may remember that the Vityazev paper (citation below) and its consequences was the subject of a 2019 dialogue in these pages between Greg Matloff and Alex Tolley (see Probing Parenago: A Dialogue on Stellar Discontinuity). And for good reason: The Gaia dataset allowed the Russian scientist and colleagues to demonstrate that Parenago’s Discontinuity was not a local phenomenon, but was indeed galactic in nature. All of this naturally leads to questions about the mechanisms at work here — Matloff’s interest in panpsychism as one explanation is well known and discussed in his book Starlight, Starbright (Curtis, 2019).

But in a new paper with Matloff, Roman Ya. Kezerashvili (New York City College of Technology) and Kelvin Long (Interstellar Research Centre, UK) point to another noteworthy datapoint. The extensive Gaia dataset showed a feature that turned up in the Hipparcos data as well. There was what the authors call a ‘strange bump in the curve of galactic revolution velocity versus (B-V) color index between (B-V) ? 0.55 and (B-V) ? 0.9…’ This would take in stars of the spectral classes G1 through K2, and the authors add that the bump is apparent only in the direction of stellar galactic revolution, like Parenago’s Discontinuity itself. Is this to be construed as a subset of the discontinuity or a separate effect? We don’t yet know.

What we do have is apparent acceleration in the direction that stars rotate around the galaxy, an unusual effect that adds up: In a billion years, the positional shift between a star without this acceleration vs. with the acceleration is about 1,500 light years.

This second apparent acceleration has yet to be confirmed by other researchers, as the authors acknowledge. But as we await that result, the new paper investigates the physical processes that could account for it. If we consider a star expelling material in a specific direction, we can model the system by analogy to a rocket and its expelled fuel, and thus examine velocity change with the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation. From the paper:

There are a number of physical mechanisms responsible for expelling mass during the stars’ life. These include but may not be limited to: unidirectional or focused electromagnetic (EM) flux, solar wind, accelerated solar wind, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), unidirectional neutrino flux, and solar wind thermonuclear fusion. Each mechanism can be treated as an exhaust velocity Vex with a mass flow rate so that the acceleration of the star is analogous to a rocket thrust F = VexMs.

What stands out here is how big the force F = 1016 N — the force needed to accelerate stars like the Sun to this level — is from our terrestrial perspective. It is the equivalent of the force exerted by two billion 106 kg rockets, each accelerating at 3g. Backing out to cosmic scale, though, the force appears less daunting, being 5 orders of magnitude less than the mutual gravitational force between the Earth and the Sun.

The mechanisms of mass loss are many and varied, as noted above, and the paper goes to work on eight of them:

- Unidirectional or focused stellar electromagnetic flux

- Galactic cannibalism

- Stellar mass loss by thermonuclear fusion

- Non-isotropic stellar wind

- Accelerated unidirectional stellar wind

- Coronal mass ejections

- Unidirectional neutrino flux

- Solar wind thermonuclear fusion

Note how many of these demand an existing advanced technology to implement them. In fact, of the eight, only two have solutions that are what Matloff calls ‘mechanistic;’ i.e. operational within nature without technological intervention. These are galactic cannibalism and stellar sass loss by thermonuclear fusion. Neither show promise as a cause for stellar acceleration of this order.

Galactic cannibalism refers to interactions between dwarf galaxies and large galaxies like the Milky Way, with the satellite galaxies being absorbed. This adds to the mass of the primary galaxy and may increase star orbiting velocities, but the authors discount the process because stellar nurseries are also accelerated by galaxy mergers, just as pre-existing stars. Stellar mass loss by thermonuclear fusion due not only to fusion within the core but via the stellar wind — which is in any case omnidirectional — likewise fails to produce the observed acceleration effect across classes of stars.

The other six options all involve the application of advanced technologies to create stellar motion in a specific direction, and some of these don’t work either. Unidirectional coronal mass ejections, for example, even if they could be shaped as thrust, fail to provide the needed energies. What emerge as viable candidates are the combined effects of a unidirectional neutrino jet and an accelerated unidirectional stellar wind “in conjunction with the unidirectional photon jet ejected from the star and non-isotropic stellar wind.” Thus on the accelerated unidirectional stellar wind:

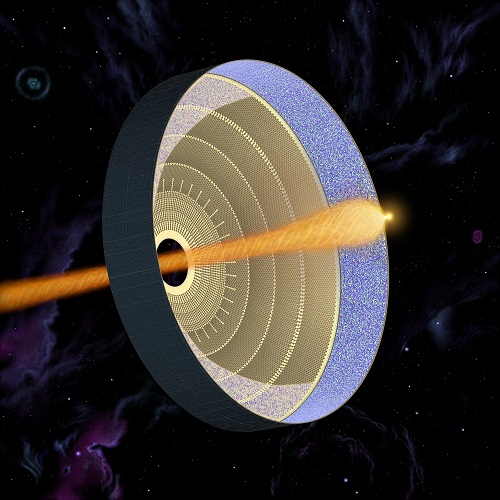

Consider the case of a dual-purpose Dyson/Stapledon megastructure constructed around a star. Confirmation of the existence of such a megastructure would constitute evidence for the existence of a Kardashev Level 2 or higher civilization. A fraction of the star’s radiant output is used to accelerate a fraction of the star’s stellar wind as a unidirectional jet.

Obviously these options take us into science fiction territory, such as the recent Greg Benford/Larry Niven collaboration beginning with Bowl of Heaven (Tor, 2012), where a star in directed motion carries with it a vast environmental shell. So as an example of just one way to do all this, let me quote from an article Benford wrote for Centauri Dreams in 2014 (see Building the Bowl of Heaven):

Our Bowl is a shell more than a hundred million miles across, held to a star by gravity and some electrodynamic forces. The star produces a long jet of hot gas, which is magnetically confined so well it spears through a hole at the crown of the cup-shaped shell. This jet propels the entire system forward – literally, a star turned into the engine of a “ship” that is the shell, the Bowl. On the shell’s inner face, a sprawling civilization dwells…

The jet passes through a Knothole at the “bottom” of the Bowl, out into space, as exhaust. Magnetic fields, entrained on the star surface, wrap around the outgoing jet plasma and confine it, so it does not flare out and paint the interior face of the Bowl — where a whole living ecology thrives, immensely larger than Earth’s area.

Image: Moving a star as depicted in Bowl of Heaven. Credit: Don Davis.

But the idea of moving stars via technology has a long pedigree. As just one example, let me quote Fritz Zwicky, that fiercely independent and prescient thinker, from an article he published in June, 1961 in Engineering and Science:

In order to exert the necessary thrust on the sun, nuclear fusion reactions could be ignited locally in the sun’s material, causing the ejection of enormously high-speed jets. The necessary nuclear fusion can probably best be ignited through the use of ultrafast particles being shot at the sun. To date there are at least two promising prospects for producing particles of colloidal size with velocities of a thousand kilometers per second or more. Such particles, when impinging on solids, liquids, or dense gases, will generate temperatures of one hundred million degrees Kelvin or higher-quite sufficient to ignite nuclear fusion. The two possibilities for nuclear fusion ignition which I have in mind do not make use of any ideas related to plasmas, and to their constriction and acceleration in electric and magnetic fields…

So could an advanced culture pull this off? The authors are quick to point out that the eight mechanisms they evaluate do not exhaust the range of possibilities, but thus far the physical mechanisms under investigation fail the test unless assisted by a technology. The first order of business, of course, will be to verify the apparent stellar acceleration and then to ponder stellar kinematics in their combined light.

But while we can envision advanced cultures developing the tools to move individual stars, as breathtaking as the concept seems, it appears unlikely in the extreme that entire stellar classes are being moved about simultaneously by megastructures or other technologies.

I think the existence of an explanation within the realm of nature has to be assumed. The question, of course, is just where it is to be found. This spirited paper, cheerfully speculative, contains an open call to the community to investigate anomalous stellar accelerations and produce other hypotheses explaining this curious behavior.

The paper is Kezerashvili, Matloff & Long, “Anomalous Stellar Acceleration: Causes and Consequences,” JBIS Vol. 74 (2021), pp. 269-275 (full text). The Vityazev paper is V. V. Vityazev et al., “New Features of Parenago’s Discontinuity from Gaia DR1 Data,” Astronomy Letters 44, 629-644 (2018). Abstract.

Good to see that the Gaia data confirms the Parenago Effect so that this is not a local anomaly, but a more general phenomenon.

What I don’t see is any suggestion that the acceleration is due to the interaction of the stellar magnetic field and the galactic field. We saw recently that M_Dwarfs have much stronger magnetic fields (Habitability: Similar Magnetic Activity Links Stellar Types. We also know that the galaxy has a magnetic field. Interactions between these fields do not require directional flares, but it is possible that varying strength of these stellar fields vs stellar mass, might be the cause of this phenomenon, especially if the galactic field is rotating.

I have no idea if the field strengths can account for the acceleration and velocity, but just maybe this is the underlying cause.

As our host says:

.

I agree.

Dear Alex

How very nice to hear from you. First, we acknowledged your contribution in our recent paper, which is free on Researchgate and the BIS website.

I don’t know whether magnetic effects can explain this phenomenon. But I encourage you to check into it.

Finally, I simply don’t know if ET, sentient stars, or a “mechanistic” explanation other than those we considered is the most plausible explanatio. But I do know that a colleague of the late Prof. Vityazev is checking te stellar acceleration results using Gaia DR3 data.

Regards, Greg

That’s good to know, Greg. I was going to ask about DR3.

Hi Greg,

Thank you for the acknowledgment in the paper. Perfect.

As far as magnetism, this might be a clue:

Stellar magnetism: empirical trends with age and rotation. Figure 2 shows that magnetism is linearly inversely proportional to age of the star and that there is 2-3 orders of magnitude range.

What may be more important for motion is the magnetic field strength relationship to mass, and this seems to cover a smaller range, suggesting that young stars might have stronger field/mass ratios.

As velocity is age-dependent, any force would be integrated over time, so the net result would be age, mass, and field strength dependent.

What might be the force operating on a star’s magnetic field? There are a some possibilities including the galactic field. One idea that could be simulated is the random closure of distance between stars. Large stars closing in on small stars would tend to result in the small star being pushed away from the large star. Is it possible that net-net that this results in small stars being pushed faster, and that over time this accumulates in one direction?

The only reason I prefer this sort of explanation relying on magnetic field strengths is that it does not require any directional ejection of stellar mass that should be observable. What I don’t like about the idea is that if it depends on relative stellar movements, these must be non-random, and worse, as the velocities increase, one would expect that over time the net force would be retarding as teh small stars run into large stars. A rotating magnetic field that pushes all the stars would seem a better bet, the net velocity being dependent on field strength, mass, and age of the star. A key question is what field strengths are required to result in the velocities observed.

One feature of either of these 2 hypothesis mechanisms requires that the stellar magnetic fields are similarly aligned. This might be observable simply by detecting the star’s rotation angle. This also requires it to be stable over long periods and not subject to random wander or “flipping” over time. Is there evidence that stellar birthplaces result in the young stars with aligned rotations and magnetic fields, or are they random?

It does seem to me that computer simulations could indicate whether magnetic fields are a possible mechanism to result in the Parenago Effect or whether the result would be random with no general velocity alignment.

Acceleration by the galactic magnetic field does seem plausible. Is this field constant? Over the lifetime of the Milky Way? How is it generated and re-generated?

Given: Cooler starts revolve “too fast”.

Or is it that hotter stars revolve “too slow”? Is this against an expected value ….or just compared to each other?

Given: Smaller, cooler stars live longer.

Perhaps they burn more efficiently than hotter stars due to convection? They’re also more prone to flares and CME’s, which are also contributors to mass loss.

Just for ease of number crunching, lets say a cool star lasts 10 billion years, and converts 10% of it’s mass to energy over it’s life span, so it effectively loses 10 % of it’s birth mass and accelerates or spirals away from the galaxy core. Lets assume this happens at a constant rate. This should move it further out in orbit at about 1500 light years per billion years, or 15,000 light years over it’s 10 billion year life. That’s a significant fraction of the radius of our galaxy. It should be quite noticeable now, there should be a segregation of stellar populations since the galaxy was born. That’s not what we see.

Do other galaxies exhibit Parenago’s discontinuity?

Dear Deanna

Thanks for the comments. I don’t really know enough about the galactic magnetic field to answer your question. But I can’t rule out magnetic effects in star motion. A Sun-like star will convert about one-ten-thousandth of its mass to energy in its 10-billion year life time. I don’t think that even Gaia is sensitive enough to tell us about Parenago’s Discontinuity in other galaxies.

Regards, Greg

I think this is probably just pseudoscience. Parenago discontinuity was not about stars having different orbital speeds (and thus experiencing different accelerations) but about stars having different velocity dispersions. This is something currently well explained as massive stars (bluer in this case) tend to be concentrated in the thin disk while the cooler stars have larger scale heights over the Galactic disk

Dear Michelangelo

Thanks for your comment. Dispersion was the initial explanation of Parenago investigators. It was abandoned because the discontinuity is ONLY in the direction of stellar galactic revolution. Then Parenago scholars including Dr. Binney began to look at the possibility of Spiral Arms Density Waves as an explanation. For this to work, dense diffuse nebula drag along less massive stars they encounter than massive stars. But the Vityazev et al paper shows that the discontinuity exists over a greater area than any diffuse nebula in the Milky Way or neighboring galaxies. Please don’t hesitate to contact me at GMatloff@citytech.cuny.edu if you need more information. I have many Parenago papers in my Parenago Folder.

Regards, Greg

First of all, thank you for your kind reply and I would certainly love to see the “parenago papers”. I will also pat attention yo your new paper in case I’ve missed the point.

For now, I strongly disagree with the way this is presented here. I will cautiously read It all again to better reply why but I’m levaing some comments that might hint in what direction I not following the arguments.

Dear Michelangelo

Please send me your e-mail address and I will send some Parenago papers. My e-mail is either GMatloff@citytech.cuny.edu or gregmat0@aol.com, I will also send the paper discussed in this Blog article. If you have coments about improving the article, please send them to Paul.

Regards, Greg

Greg, please send me a of of this paper–striking!

Dear Greg

I will be happy to do so. I have already sent one to your brother. If you don’t receive it soon, please write with an updated e-mail address. I may only have an old one. C sends her best.

Regards, Greg

I suspect this is a gravitational effect of stellar interactions in the stellar formation nebula. Stars scatter out of their formation nebula, and an interaction between a giant star and a dwarf star will result in a greater scattering velocity for the dwarf star.

Dear Dave

I don’t think that this will work. But please evaluate it further. Good luck with the concept.

Regards, Greg

I couldn’t find this on ArXiv. Such effects seem like they could be worth looking out for – we know dark matter only by its gravity, and only from astronomy, and do we know without careful observation that it pulls on all stars with precisely equal force? Could stars make an extreme test of conservation of weight that Earth-based physicists were never able to do? (I highly doubt this is the explanation but as the state lottery pushers will say, “you never know…”)

Dear Mike

Unfortunately, the paper is not on the Archive. We elected “Gold Open Access” so it is for free on the JBIS website. It is also in Researchgate. Please contact me at GMatloff@citytech.cuny.edu and I will e-mail a copy. I also wondered about Dark Matter (DM) as an explanation–but if a configuration of DM accelerates local stars, by mutual gravitation the DM should be decelerated. Then we would find DM effects closer to the galactic center rather than farther out, a s seems to be the case.

Regards, Greg

This paper attributed the shift in galactic V velocities to the _age_ of the stars (which is correlated with temperature – once you remove the white dwarfs, all the really hot stars are young). The idea is that the younger stars are closer in velocity to the orbital speed of the _gas_ in the Milky Way, which is confined by gas drag mostly to circular motions in the disk.

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2515-5172/ab2130

But if the hot(young) stars are confined initially by the gas drag, why are the older stars not so constrained? Age seems to result in higher velocities, which implies some force acting on them over time. A plateau implies some constraint on maximal velocity, or possibly an event that resets ti velocities so that the star’s age can be greater than the event’s age.

With time, stellar encounters scatter stars. And old stars have had plenty of time. This is very rarely seen on blue massive stars because of age only, but still there are runaway stars as a example. Many runaways are known to be produces by gravitacional scattering (e.g. hill’s mechanism or triple interactions like the triad of mu Col, AE Aur and Iota Ori).

There are even more scattering events to consider in the life of a star: some runaways clearly come from ejection scenarios involving supernovae. The smaller star (which Will obviusly live longer) is ejected by the kick of the shockwave of the companion.

Both dynamical ejections and supernova kicks, are able to correlate stellar mass to stellar velocities since massive stars have more inertia.

Thus there are at least two reasons why blue massive stars have lower speeds and speed dispersions, It is beacuse they are younger and they have more inertia. No need to invoke extraterrastrial intelligence of stellar consciousness here.

The mechanism you suggest would imply that there might be a higher average velocity change with older stars, but the direction would be random, not aligned with the rotation of the galaxy. It is the directionality of the average velocity difference that is puzzling.

Dear Michelangelo

You are correct about dispersions–which act in all directions. But Parenago’s Discontinuity is confirmed by researchers to act only in the direction of stellar motion around the center of the galaxy. This is why stellar kinematics experts discounted dispersion as a possible explanation. I sent you the papers your requested earlier. If you need more, please write.

Regards, Greg

Dear Marshall

The problem with explaining this phenomenon or Parenago’s Discontinuity with gas drag is that that the radius of the largest known diffuse nebula is less than the radius of the Gaia DR1 star sample, centered on the Sun.

Regards, Greg

Why not consider some kind of drag, like that of the star’s magnetic field with the ISM?

Dear Antonio

Roman, Kelvin and I could not find any magnetic drag effect that might work. But please don’t let that stop you from trying. Our purpose with going public on the Blog has beento stimulate interest. Feel free to e-mail me at GMatloff@citytech.cuny.edu to test any ideas.

Regards, Greg

In the introduction to this problem, it is stated:

“What the Soviet space scientist Pavel Parenago (1906-1960) had observed is that cooler stars, at least in the Sun’s neighborhood, revolve about 20 kilometers per second faster around the galactic center than hotter, more massive stars.”

My inclination on this is similar to several others: that the effect is related to interactions between stars of different mass, either as genuine attached binaries or in interaction within clusters.

When Parenago observed this is critical. Say, if it were circa 1930, there might not have been sufficient information to determine based on color and brightness which stars were more massive than others (e.g., mass luminosity relations). Secondly, use of the Hertzsprung Russell diagrams describing color and brightness were originally used to sort out qualities of stars within clusters. Some very tightly packed, some

more loosely. Now, we generally use the color and brightness information of a local HR diagram to derive mass, surface temperature, luminosity and presence on the main sequence or evolution off. But now, if we were to look at an individual star cluster and tag on the radial velocity variations (line of sight), I believe we would find wider velocity dispersions in the less massive stars. Stars interacting in a tight cluster would tend to shift local velocities in the same way that a chamber full of gas would have hydrogen molecules moving faster than oxygen ones.

In addition, the more massive star sampling would decrease with the age of the cluster since they would retire from the main sequence – or else gum up the theory or observation by turning into white dwarfs.

Another consideration is that IF there is such a division in rotational motion, then the picture should be held up against that of dark matter as presently understood. Our picture of dark matter (sic) is based on

galactic rotation rates presumably integrated from individual stars of varying mass and brightness. Maybe my ear has been in the wrong direction, but I haven’t heard any outcry about this issue from that quarter yet.

Best regards…

Dear WDK

Yes, Parenago’s early observations must be thought of as very preliminary. But more recent observations of larger stellar populations using Hipparcos and now Gaia beautifully show the reality of the phenomenon. Also, the Discontinuity has nothing to do with dispersion–it is only in the direction of stellar galactic revolution. But thanks for your comment.

Regards, Greg

Version that explains Parenago effect by super civilization involvement caused me to accept whole paper as huge joke…

The findings that the stellar velocities on a galactic scale do not follow the expected values are, in itself, very interesting and provocative regardless of the nationality of the researchers. The author’s speculative musings were opened-mindedness which is valued at this we site and is good science. These musings were no more outlandish than speculations made by highly respected scientists that Oumuamua may an artifact of an extraterrestrial civilization.

The paper is not a “huge joke”. The authors are to be commended for their investigations.

Dear Patient Observer

Thanks for your letter of support. My reasons for getting into this field have been described elsewhere. When I checked for data to test the hypothesis of volitional stellar motion (due to Olaf Stapledon), I was bowled over by the data. To be honest scientists, we must follow the data no matter what the level of criticism. Avi Loeb indeed is very courageous for his stance on Oumuamua.

Regards, Greg

Not a joke!

Could this be because of the LMC and SMC encounter with milky way? These younger massive stars may have been created in recent encounters. The giant Omega globular star cluster also swept thru the galaxy along with many others globular clusters on a regular basis. Omega was probably a dwarf galaxy before the last encounter and there are many dwarf galaxies surrounding the milky way. The star burst type galaxies may of been what the milky way was not to long ago – the starburst of large bright stars. As in quantum entanglement maybe the milky way has a more vivid history to tell…

Dear Michael

I don’t think that this works, but I may be wrong. Please check the numbers. If the milky Way were a starburst galaxy earlier in its evolution, why did this excessive star production end before our galaxy became a giant elliptical??

Regards, Greg

Greg, The Globular star clusters and Dwarf galaxies orbit around the Milkyway and cross thru its arms roughly the same as our revolution around the galaxy. So every 135 million years they pass thru the arms.

When they go thru the thicker areas of the arms this should set off a local starburst of large short lived stars O,B,A and maybe upper end of the F. The larger galaxies such as LMC and SMC are on a much larger orbit but would also cause a much larger starburst area as they moved thru the Milkyways arms. Another words there are starburst going on all the time as you can see when two large galaxies collide.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/Antennae_galaxies_xl.jpg/1920px-Antennae_galaxies_xl.jpg

https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/thumbnails/image/potw1909a.jpg

https://www.astrobin.com/full/287667/0/

This is anecdotal, of course, but Barnard’s star ( cool, faint and very close) has a high proper motion even for its proximity. It is suspected of being one of those interlopers from cluster passages.

Dear WDK

You are correct. Barnard’s Star is a Pop. 2 star, probably from a globular cluster in our galaxy’s halo. It may have been scattered to our neighborhood by “gravity assists” with cluster stars.

Regards, Greg

Could it be the UV that these massive stars put out, they would ionise huge swaths of gases and dust in space which perhaps the galatic magnetic fields interact with and so creates a braking effect.

A bit like this,

http://www.outerspacecentral.com/images/bow_shock.jpg

How these observations agree with orbital mechanics? If in a given volume of galactic space, some stars have more orbital velocity, it means elongated orbits with periapses near this volume and apoapses on the opposite side of GC. But if redder population just has more elliptic orbits, and major axes are oriented randomly, then equal subpopulation would have apoapses in the same volume, with apparent velocities slower by the similar amount. Or there would be an excess of slower-moving stars outwards of our position. Likewise, directional velocities discontinuity could be explained with different inclinations for different populations.

I expected that after Gaia data releases, Parenago discontinuity would dissolve or give way to more detailed explanation, maybe some differences in kinematics due to early tidal or galactic merger event(s), or some combinations of these.

In is interesting although, if the precision and statistics of Gaia DRs could allow for studies of non-gravitational interactions (or maybe non-uniform dark matter distribution?). Heliosphere interactions are responsible for stellar spin-down, which could amount to several hundreds of km/s of rotational velocity – it is natural to suppose that they could influence orbital velocities to some extent as well. Stellar magnetospheres are much more widespread than planetary ones, due to the interlock of stellar winds and magnetic fields – they are somewhat akin to plasma-inflated M2P2 sails. With this in mind, it’s much easier to believe that interaction between vanishing galactic magnetic fields and huge stellar mass, over eons, could result in some visible effects on orbital motion. And much less easy to think of observable effects of stellar orbital engineering. Unambigous signs have to be something more subtle, like some impossible precise arrangements (searched by a low-entropy-seeking neural), or outstanding, like a star flying at a fraction of c on an in-bound trajectory.

I will toss this idea in the mix with no expectation of serious consideration. The B-V index is likely correlated with stellar mass. Could the much-discussed MOND gravity conjecture used to account for the apparent discrepancy in stellar orbital velocity (rather than the presence of Dark Matter) be at work through some secondary effect? It would be helpful if researchers could investigate the correlation between stellar mass and the discrepant velocity.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modified_Newtonian_dynamics

I have a question for Greg: The orbital velocity of stars around the galaxy around where the sun is 250 km/sec. 20 km/sec is about 8% of this. If you have an object in a circular orbit and increase its velocity by 8%, its going to go into an elliptical orbit. Did you look into any correlation between the orbital eccentricity of star and their color index?

That is an interesting suggestion. What if the stars are getting some extra velocity and we are seeing an orbital change, e.g. a gravitational assist from the galaxy’s BH? Would the stellar type relationship to age and hence excess velocity be due to the number of passes of this slingshot? 2 BHs in orbit around each other at the core could be a gravitational slingshot and we are seeing the result of this effect on stars after a number of passes.

The problem I see with this idea is that the orbit would likely be highly eccentric and thus the velocity in the direction of the core would be both high and in excess in both directions (inward and outward bound). Possibly the path of the star travels outwards and then gets influenced by the stars in the spiral arms so that the orbit becomes more circular. But if so, are multiple passes possible, or is this a one-shot event and has something to do with stellar mass alone?

Alternatively binaries with massive stars in alignment with the galactic rotation, but out in the spiral arms might well offer the same gravity slingshots, although the direction of the slingshot seems to be rather constrained. Why would this model not generate random slingshot directions?

Another thought. The rotation of the stars in the galaxy does not conform to an orbit around a gravitational point, but rather is faster as the radial distance from the galaxy’s center increases. IOW, the stars at the galaxy’s edge have a higher velocity than those further in.

Now suppose a star on the edge starts to fall inwards towards the core. It will retain its velocity and probably also increase its velocity. By the time it reaches our neighborhood, it is travelling faster than the local stars.

What about stellar type? If age is truly a factor, it would be due to the amount of radius reduction, IOW, how long the star has been falling inwards. Older stars would have had more time to lose their orbital radius and hence be traveling faster than the local stars, whilst younger stars will only have reduced their orbital radii a little and their relative velocity to the local stars would be less.

If that model is correct, the issue then becomes what is the perturbing force that sets stars on a course that reduces their orbital radius in the galaxy – galactic collision? something else?

A BoE calculation for an M_dwarf spiraling in from a slightly greater distance to the galactic center than our sun.

Using:

solar distance to center of galaxy = 26 kly

solar rotation velocity = 227 kps.

Assume a simplified galaxy of uniform stellar density such that the rotation velocity obeys:

V = V_R(r/R) where: r = solar distance to center, R is radius of the edge of the galaxy disk, V_R = rotation velocity of stars at edge of disk.

Let us use R=33 kly as an example of the disk edge as is often depicted for the sun, rather than 50+ kly.

227 = V_R*(26/33), V_R = 288 kps.

Assume that a local M_dwarf has spiraled in from an orbit that is further out from the center of the galaxy, and is now 20 kps faster than the sun’s orbit due to retaining its velocity from its original orbit.

V = 227 + 20 = 288*(r/33).

r = 28.3 kly.

Thus the M_dwarf started at 28.3 kly out, or 2.3 kly further out than the sun, and has spiraled in after 5 by or so.

because the eqn is linear, the value of R is immaterial, and the same values work for R = 50 kly, with a concomitant V_R of 436.5 kps.

Younger, hotter stars would have had less time to spiral inwards, and thus their starting orbit would be between that of our sun and the M_dwarfs in this caluculation.

The calculation doesn’t require this simple model, just that the rotation of the stars in the galaxy is not Keplerian so that stars further from the galaxy center rotate faster than those closer to the center. A more accurate model can be used to make a similar calculation.

I make no hypothesis as to what is the force that is causing stars to spiral inwards, other than this model does explain the observation with the proviso that the “Parenago plateau” seems to occur at around the assumed stellar age of ~ 7by which might indicate that the perturbing event started 7 bya.

Nit on paper.

Eqn 1 uses the standard version V = SQRT(GM/r) to determine mass at the center of the galaxy. However, we know the stars in the galaxy do not obey this as the rotation speed is more constant due to the hypothesized halo of dark matter around our galaxy.

Doesn’t this affect your calculation of the mass of the stellar matter inside the solar orbit of 10^11 solar masses?

Galaxy rotation of M33.

Rotation curve of stars in M33 galaxy

The rotation rate looks much flatter for our galaxy, which would falsify my hypothesis if the rotation rate stays constant as indicated in this image. [However, note the far wider error bars compared to M33 data and the limited radius of the data. Perhaps the M33 data is a better example of the true nature of our galaxy’s rotation rate.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milky_Way#Galactic_rotation (Milky Way

Whatever the reason for any inward spiraling of stars, the Parenago Effect seems to limit any continuous spiraling in for about 7 by. This is about 1/2 the age of the galaxy. This suggests that the start of the inward movement of stars started during the galaxy’s middle-age, perhaps due to some event, such as a galaxy collision.

This 2019 paper shows that from 5-25 kpc the rotation velocity has a very shallow decline with radius.

The Circular Velocity Curve of the Milky Way from 5 to 25 kpc

If this relationship holds beyond 25 kpc, it invalidates my hypothesis as the M_dwarfs would have to migrate outwards rather than inwards and still maintain their higher velocity. The change in velocity with radius is so shallow that I don’t think this can work at all, so the hypothesis probably falsified.

Alex, my thinking on this over the weekend is the following:

Suppose we turn the narrative on its head and assume that most of the stars in the galaxy are normal, but that the Blue Giants are going 20 km/sec slower on average than everything else.

This can be account for if we assume that the giants have more elliptical orbits, on average, than other stars.

For modeling purposes, assume a uniform galaxy with stars rotating around its center faster towards the center and slower further out. Now, assume most stars follow near circular orbits around the galaxy, but the blue giants for some reason have elliptical orbits.

For half their orbit, the giants will be moving faster than the surrounding stars. For the other half the orbit slower. But an orbiting body in an ellipse spends more time at its apogee than its perigee, so at any given time you will see more blue giants near their apogee than their perigee. This will mean that when average out their velocities, their average velocity around the galaxy will appear to be slower than the surrounding stars.

This effect can be enhanced if the number of blue giants falls off with distance. There will be less blue giants plunging in past the observer than rising from the inner galaxy.

I understand what you are saying,. What I don’t understand is why are the heavier stars in more elliptical orbits than lower mass stars? Any idea why that might be?

I could come up with some suggestions, like for instance, blue giants often form in triples, which are unstable until one star is ejected and the other two settle into a close binary; but the main thrust of my explanation is that this behavior can be accounted for through simple orbital mechanics and that exotic explanations aren’t needed unless the simple ones first fail (Occam’s razor.)

What I think is needed now is more information about the orbital parameters and orbital distribution of these stars.

This 2019 paper shows that from 5-25 kpc the rotation velocity has a very shallow decline with radius.

The Circular Velocity Curve of the Milky Way from 5 to 25 kpc

If this relationship holds beyond 25 kpc, it invalidates my hypothesis as the M_dwarfs would have to migrate outwards rather than inwards and still maintain their higher velocity. The change in velocity with radius is so shallow that I don’t think this can work at all, so the hypothesis is probably falsified.

From: “Passing Starship”

To: https://centauri-dreams.org/2021/08/20/how-to-explain-unusual-stellar-acceleration/

Subject: “On ‘How to Explain Unusual Stellar Acceleration?’: The Virial Theorem.”

Timestamp: 20210823-20 UTC

I’m a long time lurker on this site, but I feel that I must post what I think is the most likely answer.

The Virial Theorem states that for gravitationally bound systems in dynamic equilibrium, the mean kinetic energy of its constituents is equal to half their mean potential energy. The fact that this is true for what is otherwise a very complicated dynamical system is somewhat akin to thermodynamic results, such as ‘temperature’ is a measure of kinetic energy that is not in the form of a bulk motion, but instead randomised motion relative to that bulk motion.

In these systems, there tends to be an equipartition of energy, so that for a mixed gas of oxygen and hydrogen, then (as “wdk” wrote above on 21 August 2021 at 20:51), the hydrogen molecules have a much higher mean speed (by four times, I think), as they have one sixteenth the mass of oxygen molecules. This equipartition comes about because the multitude of collisions between molecules provides the mechanism to exchange kinetic energy, and each kind of molecule tends to gain equal averages of energy.

I suspect what happens for the stars of a galaxy is that a multitude of close stellar passes allows exchanges of kinetic energy, too. (These need the rest of the galaxy’s mass to act as a ‘third body’ to allow the exchange, of course.) However, just as hydrogen molecules end up moving faster than oxygen molecules by virtue of being so much lighter, so too light stars end up being flung on faster trajectories than heavy stars. Yet, the stars (as part of a galaxy’s general revolution) have had their trajectories largely set by the orbital angular momentum they inherited at birth, and as “Dave Moore” wrote above on 22 August 2021 at 15:13 the scattering effect seems to be of order 8% of general orbital motion. So, unlike for a thermodynamical system such as a gas, the stars still tend to have a dominant bulk orbital motion, so the divergence in orbital speed is highly directional.

So, what I’m thinking is that the myriads of mutual stellar encounters that stars have will tend to cause heavy stars to give kinetic energy or orbital angular momentum away to light stars. Heavy stars will tend to slow down, and so sink towards the galactic centre, while light stars will tend to speed up and drift away from the galactic centre.

Now, people might think: “but wait a moment, if a heavy star can drop by accelerating a lighter star outward, why can’t it be equally likely that a heavy star can raise by flinging a lighter star inwards, or pulling the lighter star back?”

I concede this can happen, but I think the Parenago effect comes about because there is a bias as to which kind of encounter is more likely.

I can think of two natural manifestations of this effect.

1) The Trapezium star system and ‘hierarchical multiple star systems’. Michelangelo Pantaleoni mentioned above on 21 August 2021 at 17:47 the runaway stars Mu Col, AE Aur, and Iota Ori. I recall that these trace back to the Trapezium system (in the Orion Nebula, M42), and are believed to have been ejected by the heavier stars in the system. The remaining stars (four of them) orbit in a hierarchcal manner: the heaviest is at centre, the next heaviest is next out, and so forth. It seems that during settlement, the most likely outcome is that the heaviest stars sink furthest to the centre of the system. Note though that for the lightest stars to have moved to the farthest orbits, they would have to have been given an orbital speed boost to get out there (and orbital circularisation could have been provided with extra-system stellar encounters in the formational cluster). Please note to avoid confusion: I’m not mentioning the runaway stars of the Trapezium system here as the cause of the Parenago effect, as I think Michelangelo Pantaleoni was suggesting, but as an illustration of the mechanism that is the cause. I hope I’m clear.

2) Planetary Systems. I know there are exceptions, but by the same token as above, I suspect most planetary systems will also have their heaviest planets (the gas giants) arranged in a similar hierarchical manner. In our system, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, follow this pattern almost perfectly (and the Nice model has it that they used to follow it perfectly, with Uranus and Neptune swapped). In general, if planetary systems undergo phases where the largest planets form in the same regions, they will perturb each other, but the heaviest will tend to drop towards their star the most (hence why there are ‘Hot Jupiters’), yet the lightest planets will tend to scatter outwards even more, such as Neptune and perhaps the proposed Planet Nine.

Now, Alex Tolley’s comment of 22 August 2021 at 20:05 is interesting. First, he’s close to suggesting what I have, but I think there’s something backwards: the Parenago effect is not a result of the non-Keplerian galactic rotation curve, but a partial (yet minor) contribution to it. As the galaxy maintains its Virial theorem balance, all those light stars are being pumped upwards and outwards by heavy stars falling inwards and downwards. These light stars are the most numerous, and must have an excess of orbital speed compared to circular orbits most times to be able to keep on drifting outwards. As for the age of stars, I think that’s a red herring. Most of the mass of a massive star will remain close to where the star should have been even after its death.

I wonder if the Asteroid Belt shows a similar effect to Parenago’s?

If my proposal turns out not to be true, I’ve got Arnold J Rimmer here telling me it’s definitely aliens! :)

If anyone needs a response from me, as I like to stay quiet and anonymous on the interwebs behind Tor+Tails (I don’t actually have even a real e-mail address and never enable javascript), it’ll have to be right here on this comments section. Just ask.

According to general astrophysics, the mass of the individual star is ignored due to the larger mass of the galaxy inside the stars orbit. Our galaxy has a differential rotation based on the distance star so it’s orbital velocity increases the further away it is from the center of the galaxy starting at 220 km per second and reaches 250 km pre second at 8 kiloparsecs. Consequently all classes stars move relatively the same speed at the same distance. The difference is the gravity on the star which is controlled by generally relativity and not newtons third law as in a rocket since there is angular momentum and free fall around the black hole at the center

Also firing some high energy particles at nearly the speed of light at the surface of the Sun will not produce nuclear fusion in an efficient way because the particle radiation cross section and particle density is too low there, but the radiation cross section, gravity and pressure is very high at the center of the Sun which is why the temperatures necessary for fusion only exits in the inner 25 percent of the Sun. We could detonate hydrogen bombs on the surface of the Sun, but that would not be efficient to move the Sun and I don’t think stars can be made into rocket engines or move in such a way due to their large mass. Why not just build one’s own efficient nuclear fusion rocket engine which would be a lot less massive and expensive and make the Dyson sphere completely obsolete since fusion is the power source of our future, it’s just a matter of time.

The fusion of hydrogen into helium also requires confinement and compression and the magnetic field and gravity are not strong enough to do that on the surface of the Sun.

Also hydrogen is not fused directly into helium in all classes of stars which always need the intermediate steps through the weak nuclear force in a process called the proton proton chain. The final state of the proton proton chain combines two helium 3 atoms together. There is no helium 3 on the surface of the sun but only in the center. Accelerating particles into relativistic stream into the Sun would not allow enough control of the fusion so once in a while a few particles might fuse and one would have to fire several isotopes of hydrogen at the same time.. In other words, virtually no fusion radiation cross section

I have seen mention of the Galaxy’s BH (in the center, quite a beauty!) only a couple of times, or so. I have not, however, seen the following possibility explored:

Let us assume that the GBH is exerting a tremendous magnetic field throughout the Galaxy. It’s possible; it’s that big. This is to be differentiated from the general magnetic field of the general Galaxy. This one could be emanating from a rotating object. While I have not seen research on rotation of our GBH, I suspect it might be considerable. So, what if the GBH’s rotation is causing a rotating magnetic field? And, what if this rotating magnetic field is interacting with stars in a way that produces the motions observed? It would be like a very powerful magnet that is interacting with other magnets. The force on the other magnets would be different based on their strength and strength of interaction with the primary magnet. Would this be a possible explanation? If it is, could further research reveal more information about the GBH?

A magnetic field is part of the electromagnetic force which only is strong on the small scales and short distance like magnets. There are an equal number of positive and electric charges which cancel each other out in large bodies so the EM force can’t more large bodies like stars, planets etc Gravity dominates on the large scales.

So ion engines cannot work? ;) Gravity can dominate, but that doesn’t mean that weaker forces cannot perturb bodies, especially is the effect is cummulative.

Ion engines can’t push planets and stars.

Sure they can. You just are not thinking big enough. Use the same technique as a robotic probe to move an asteroid by gravitational attractor. Place Ion engines away from the sun with enough mass to pull the sun towards it, while simultaneously thrusting away from the sun to maintain its distance. This is fundamentally no different than using deflectors to create an asymmetric solar radiation emission to move the sun. The acceleration is very small, but the velocity will accumulate over billions of years.

Gravity will overcome any wind opposing the fall of a snooker ball to fall to the ground if dropped. But place that ball on a snooker table, and even a gentle breath can move it.

Apply the same reasoning to a star. An orbit balances the pull of gravity so that the orbital path is now like that snooker table. Any small force on that star applied over time will move it, regardless of how low the acceleration is.

Technically, you are correct Alex Tolley, but compared to gravity and space warp technology, ion power is stone knives and bear skins. Gravity is much more powerful for propulsion, the ultimate in efficiency, energy saving, and ability to move large objects over long distance.

Force or dissipation of force in what we would consider low density media are often difficult to evaluate. E.g., when it comes to upper atmosphere drag, I often find I make mistakes because my sense of drag forces on a log scale is rather weak. Ditto for this situation with a possible galacticdrag providing a decelerating or accelerating magnetic field.

Beside the relative intensity and dimensions of a G2V magnetic field and that of a red dwarf there is also their inherent mass densities.

Since Jupiter and the sun are about the same density, but differ in mass by a factor of a thousand, we should stop to consider the density of red dwarfs of about a tenth the radius of the sun and about a tenth its mass.

To that rough order they are about 100 times as dense.

So, for accelerating or decelerating objects in the galactic medium, this

would have two consequences. Calculation of surface magnetic field

intensities would differ, but also the nature of the bowling ball rolling

through a retarding medium, how much its momentum would be dissipated.

In effect, why not suggest that the more dense objects maintain more of their original momentum and the less dense objects tend to dissipate more? I would also suspect that a 25 km/sec difference ( out of 250 km/sec nominal orbital) would have some more spread ( plus or minus) when other features are examined (e.g., age and spectral classification).

As I had no idea that the densities of stars were so different, I have added this reference table to illustrate your point:

Number Densities of Stars of Different Types in the Solar Vicinity

A. T.,

Thanks! That is a useful table: for densities, population distributions and likely more when I get a chance to delve into it.

Perhaps I am not alone in being confused in which stars are being compared to which in this enterprise. I had just sent off a note comparing red dwarfs and solar main sequence stars based on density. Also, like others I examined the issues of main sequence binaries of differing mass, or else interaction events. However, I now note that the Vityzev paper abstract does not address such comparisons. Rather it is examining main sequence stars and red giants. As to whether Parenego

in his earlier work was addressing one or the other, I hesitate to say.

But from the standpoint of trying to find an explanation for velocity dispersions, this consideration does make a difference: with respect to magnetic field – and certainly stellar density. Mass of a giant like Betelguese is not much different from the sun’s but OVERALL density is different by orders of magnitude. I suspect that in the case of core densities the relation is reversed. But if overall magnetic field is interacting with a galactic field, the overall cohesion of the star would favor the surface layers and core moving together.

As to the case of the Bowl of Heaven as illustrated, that just might leave something behind….