Colonies on other worlds are a staple of science fiction and an obsession for rocket-obsessed entrepreneurs, but how do humans go about the business of living long-term once they get to a place like Mars? Alex Tolley has been pondering the question as part of a project he has been engaged in with the Interstellar Research Group. Martian regolith is, shall we say, a challenge, and the issue of perchlorates is only one of the factors that will make food production a major part of the planning and operation of any colony. The essay below can be complemented by Alex’s look at experimental techniques we can use long before colonization to consider crop growth in non-terrestrial situations. It will appear shortly on the IRG website, all part of the organization’s work on what its contributors call MaRMIE, the Martian Regolith Microbiome Inoculation Experiment.

by Alex Tolley

Introduction: Food Production Beyond Hydroponics

Conventional wisdom suggests that food production in the Martian settlements will likely be hydroponic. Centauri Dreams has an excellent post by Ioannis Kokkinidis on hydroponic food production on Mars, where he explains in some detail the issues and how they are best dealt with, and the benefits of this form of food production [1]

Still from a NASA video on a Mars base showing the hydroponics section.

A recent NASA short video on a very stylish possible design for a Mars base (see still above) shows a small hydroponics zone in the base, although its small size and what looks like all lettuce production would not be sufficient to feed one person, and that is before the monotonous diet would drive the crew to wish they had at least some potatoes from Mark Watney’s stash that could be cooked in a greater variety of ways.

I would tend to agree with the hydroponic approach, as well as other high-tech methods, as these food production techniques are already being used on Earth and will continue to improve, allowing a richer food source without needing to raise animals. Kokkinidis raises the issue of animal meat production for various cuisines, but in reality, the difficulties of transporting the needed large numbers of stock for breeding, as well as the increased demand for primary food production, would seem to be a major issue. [It should be noted that US farming occupies perhaps 2% of the population, yet most commentators on Mars groups seem to think that growing food on Mars will be relatively easy, with preferred animals to provide meat. How many Mars base personnel would be comfortable killing and preparing animals for consumption, even mucking out the pens?]

Hydroponics today is used for high-value crops because of the high costs. Many crops cannot be easily grown in this way. For example, it would be very difficult to grow tree fruits and nuts hydroponically, even though tree wood would be a very useful construction material. On Earth, hydroponics gains the highly desirable much-increased production per unit area coupled with a very high energy cost. It also requires inputs from established industrial processes which would have to be set up from scratch on Mars. Should there need to be lighting as well, low-energy LEDs would be hard to manufacture on Mars and would, initially at least, be imported from Earth.

Hydroponics is attractive to those with an engineering mindset. The equipment is understood, inputs and outputs can be measured and monitored, and optimized, and it all seems of a piece with the likely complexity of the transport ships and Mars base technology. It may even seem less likely to get “dirt under the fingernails” compared to traditional farming, a feature that appeals to those who prefer cleaner technologies. Unfortunately, unlike on Earth, if a critical piece of equipment fails, it will not be easily replaceable from inventory. Some parts may be 3D printable, but not complex components, or electronics. Failure of the hydroponic system due to an irreplaceable part failure would be catastrophic and lead to starvation long before a replacement would arrive from Earth. If ever there was a need for rapid cargo transport to support a Martian base, this need for rapid supply delivery would be a prime driver [4].

Soil from Regolith

Could more traditional dirt farming work on Mars, despite the apparent difficulties and lack of fine control over plant growth? The discovery that the Martian regolith has toxic levels of perchlorates and would make a very poor soil for plants seems to rule out dirt farming. If the Gobi desert is more hospitable than Mars, then trying to farm the sands of Mars might seem foolhardy, even reckless.

However, after working on a project with the Interstellar Research Group (IRG), I have to some extent changed my mind. If the Martian regolith can be made fertile, it would open up a more scalable and flexible method to grow a greater variety of plant crops than seems possible with hydroponics. Scaling up hydroponics requires far more manufacturing infrastructure than scaling up farming with an amended regolith if regolith remediation does not require a lot of equipment.

So the key questions are how to turn the regolith into viable soil to make such a traditional farming method viable, and what does this farming buy in terms of crop production, variety, and yields?

The first problem is to remove the up to 1% of perchlorates in the regolith that are toxic to plants. While perchlorates do exist naturally in some terrestrial soils, such as the Atacama desert, they are at far lower concentrations. Perchlorates are used in some industrial processes and products (e.g. rocket propellant, fireworks), and spills and their cleanup are monitored by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the USA. Chlorates were used as weedkillers and are potent oxidizers, a feature that I used in my teenage rocket experimentation, but are now banned in the EU.

There are 2 primary ways to remove perchlorates. If there is a readily available water supply, the regolith can be washed and the water-soluble perchlorates can be flushed away. The salt can be removed from the perchlorate solution with a reverse osmosis unit, a mature technology in use for desalination and water purification today. In addition, agitation of the regolith sand and dust can be used to remove the sharp edges of unweathered grains. This would make the regolith far safer to work with, and reduce equipment failure due to the abrasive dust damaging seals and metal joints. Agitation requires the low technology of rotating drums filled with a slurry of regolith and water.

A second, and more elegant approach, is to bioremediate with bacteria that can metabolize the regolith in the presence of water [5,6,7,8]. While it would seem simple to just sprinkle the exposed Martian surface with an inoculant, this cannot work, if only because the temperature on the surface is too cold. The regolith will have to be put into more clement conditions to maintain the water temperature and at least minimal atmospheric pressure and composition. At present, it is unknown what minimal conditions would be needed for this approach to work, although we can be fairly certain that terrestrial conditions inside a pressurized facility would be fine. There are a number of bacterial species that can metabolize chlorates and perchlorates to derive energy from ionized salts. A container or lined pit of graded regolith could be inoculated with suitable bacteria and the removal of the salt monitored until the regolith was essentially free of the salt. This would be the first stage of regolith remediation and soil preparation.

There is an interesting approach that could make this a dual-use system that offers safety features. The bacteria can be grown in a bioreactor, and the enzymes needed to metabolize perchlorates extracted. It has been proposed that rather than fully metabolizing the salt to chloride, enzymes could be applied that will stop at the release of free oxygen (O2). This can be used as life support or oxidant for rocket fuel, or even combustion engines on ground vehicles. The enzymes could be manufactured by gene-engineered single-cell organisms in a bioreactor, or the organisms can be applied directly to the regolith to release the O2 [10]. The design of the Spacecoach by my colleague, Brian McConnell, and me used a similar principle. As the ship used water for propellant and hull shielding, in the case of an emergency, the water could be electrolyzed to provide life-supporting O2 for a considerable time to allow for rescue [9]. Extracting oxygen from the perchlorates with enzymes is a low-energy approach to providing life support in an emergency. A small, portable, emergency kit containing a plastic bag and vial of the enzyme, could be carried with a spacesuit, or larger kits for vehicles and habitat structures.

After the perchlorate is removed from the regolith, what is left is similar to broken and pulverized lava. It may still be abrasive, and need to be abraded by agitation as in the mechanical perchlorate flushing approach.

So far so good. It looks like the perchlorate problem is solved, we just need to know if it can be carried out under conditions closer to Martian surface conditions, or whether it is best to do the processing under terrestrial or Mars base conditions. If the bacterial/enzyme amendment can be done in nothing more than lined and covered pits, or plastic bags, with a heater to maintain water at an optimum temperature, that would be a plus for scalability. If the base is located in or near a lava tube, then the pressurized tube might well provide a lot of space to process the regolith at scale.

Like lunar regolith, it has been established that perchlorate-free regolith is a poor medium for plant growth. Experiments on Mars Regolith Simulant (MRS) under terrestrial conditions of temperature, atmospheric composition, and pressure, indicate that the MRS needs to be amended to be more like a terrestrial soil. This requires nutrients, and ideally, structural organic carbon. If just removing the perchlorates, adding nutrients, and perhaps water-retaining carbon was all that was needed, this might not be too dissimilar to a hydroponic system using the regolith as a substrate. But this is really only part of the story in making fertile soil.

Nitrogen in the form of readily soluble nitrates can be manufactured on Mars chemically, using the 1% of N2 in the atmosphere. It is also possible nitrogen rich minerals on Mars may be found too. Phosphorus is the next most important macronutrient. This requires extraction from the rocks, although it is possible that phosphorus-rich sediments also may be found on Mars.

To generate the organic carbon content in the regolith, the best approach is to grow a cover crop and then use that as the organic carbon source. Fungal and bacterial decomposition, as well as worms, decompose the plants to create humus to build soil. Vermiculture to breed worms is simple given plant waste to feed on, and worm waste makes a very good fertilizer for plants. Already we see that more organisms are going to have to be brought from Earth to ensure that decomposition processes are available. In reality, healthy terrestrial soils have many thousands of different species, ranging in size from bacteria to worms, and ideally, various terrestrial soils would be brought from Earth to determine which would make the best starting cultures to turn the remediated regolith into a soil suitable for growing crops.

Ioannis Kokkinidis indicated that Martian light levels are about the same as a cloudy European day. Optimum growth for many crops needs higher intensity light, as terrestrial experiments have shown that for most plants, increasing the light intensity to Earth levels is one of the most important variables for plant growth. This could be supplied by LED illumination or using reflective surfaces to direct more sunlight into the greenhouse or below-ground agricultural area.

One issue is surface radiation from UV and ionizing radiation. This has usually resulted in suggestions to locate crops below ground, using the surface regolith as a shield. This may not be necessary as a pressurized greenhouse with exposure to the negligible pressure of Mars’ atmosphere, could support considerable mass on its roof to act as a shield. At just 5 lbs/sq.in, a column of water or ice 10 meters thick could be supported. It would be fairly transparent and therefore allow the direct use of sunlight to promote growth, supplemented by another illumination method.

Soil is not a simple system, and terrestrial soils are rich ecosystems of organisms, from bacteria, fungi, and many phyla of small animals, as well as worms. These organisms help stabilize the ecosystem and improve plant productivity. Bacteria release antibiotics and fungi provide the communication and control system to ensure the bacterial balance is maintained and provide important growth coordination compounds to the plants through their roots. The animals feed on the detritus, and the worms also create aeration to ensure that O2 reaches the animals and aerobic fungi and bacteria.

Most high-yield, agricultural production destroys soil structure and its ecosystems. The application of artificial fertilizers, herbicides to kill weeds, and pesticides to kill insect predators, will reduce the soil to a lifeless, mineral, reverting it back to its condition before it became soil. The soil becomes a mechanical support structure, requiring added nutrients to support growth.

Some farmers are trying new ideas, some based on earlier farming methods, to restore the fertility of even poor soils. This requires careful planting schedules, maintenance of cover crops, and even no-tilling techniques that emulate natural systems. Polyculture is an important technique for reducing insect pests. Combined, these techniques can remediate poor soils, eliminate fertilizers and agricultural chemicals, improve farm profitability, and even result in higher net yields than current farm practices. [11]

Without access to industrial production of agricultural chemicals and nutrients, these experimental farming practices will need to be honed until they work on Mars.

Given we have regolith-based soil what sort of crops can be grown? Almost any terrestrial crop as long as the soil conditions, drainage, pH, and illumination can be maintained.

Unlike on Earth where crops are grown where the conditions are already best, on Mars, it might well be that the crops grown will be part of a succession of crops as the soil improves. For example, in arid regions, millet is a good crop to grow with limited water and nutrients as it grows very easily under poor conditions. Ground cover plants to provide carbon and that fix nitrogen might well be a rotation crop to start and maintain the soil amendment. As the soil improves, the grains can be increased to include wheat and maize, as well as barley. With sufficient water, rice could be grown. None of these crops require pollinators, just some air circulation to ensure pollination.

For proteins, legumes and soy can be grown. These will need pollinating, and it might well be worth maintaining a greenhouse that can include bees. Keeping this greenhouse isolated will prevent bees from escaping into the base. As most of our foods require insect pollination, root crops like potatoes, carrots, and turnips, can be grown, as well as leafy greens like lettuce, and cabbage. The pièce de résistance that dirt farming allows is tree crops. A wide variety of fruit and nuts can be grown. Pomegranates are particularly suited to arid conditions. The leaf litter from such deciduous trees will be further input to improve the soil.

So the soil derived from regolith should allow a wider variety of crops to be grown, and with this, the possible variety of cuisine dishes can be supported. Food is an important component of human enjoyment, and the variety will help to keep morale high, as well as provide an outlet for prospective cooks and foodies.

Are there other benefits? As any gardener knows, growing food in the dirt is less time-consuming than hydroponics as the system is more stable, self-correcting, and resilient. This should allow for more time to be spent on other tasks than constantly maintaining a hydroponic system, where a breakdown must be fixed quickly to prevent a loss.

Meat production is beyond the scope of this essay. I doubt it will be of much importance for two main reasons. Meat production is a very inefficient use of energy. It is far better to eat plants directly, rather than convert them to meat and lose most of the captured energy. The second is the difficulty of transporting the initial stocks of animals from Earth. The easiest is to bring the eggs of cold-blooded animals (poikilotherms) and hatch them on Mars. Invertebrates and perhaps fish will be the animals to bring for food. If you can manage to feed rodents like rabbits on the ship, then rabbits would be possible. But sheep, goats, and cows are really out of the question. A million-resident city might best create factory meat from the crops if the needed ingredients can be imported or locally manufactured. My guess is that most Mars settlers will be Vegetarian or Vegan, with the few flexitarians enjoying the occasional fish or shrimp-based meal.

If you have read this far, it should be obvious that dirt farming sustainably, is not simple, nor is it easy or quick. A transport ship carrying settlers to Mars will have to supply food to eat until the first food crops can be grown. That food will likely be some variant of the freeze-dried, packaged food eaten by astronauts. Hopefully, it will taste a lot better. The fastest way to grow food crops will be hydroponics. All the kit and equipment will have to be brought from Earth. With luck, this system will reduce the demand for packaged food and become fairly sustainable, although nutrients will have to be supplied, nitrogen in particular. I don’t see sacks of nitrogen fertilizer being brought down to the surface, but instead, there may be a chemical reactor to extract the nitrogen in the Martian air and either create ammonia or nitrates for the hydroponic system.

But if the intention, as Musk aims, is to make Mars a second home, starting with 1 million residents, the size of the population that is large enough to provide the skills for modern civilization, then food production is going to need to be far more extensive than a hydroponics system in every dome or lava tube. The best way is to grow the soil as discussed above. This will not be quick and may take years before the first amended regolith becomes rich loamy, fertile soil. The sterile conditions on Mars mean that there will be no free ecosystem services. Every life form will have to originate on Earth and be transported to Mars. But life replicates, and this replication is key to success in the long term. There will be a mixture of biodiverse allotments and tracts of large-scale arable farming. Without some new technology to deflect ionizing radiation, the Martian sunlight will probably need to be indirect and directed to the crops protected by mass shields. Every square meter of Martian sunlight will only be able to support ½ a square meter of crops, so there may need to be an industry manufacturing polished metal mirrors to collect the sunlight and redirect it.

Single-cells for artificial food

Although our sensibilities suggest that the Martian settlers will want real food grown from recognizable food crops, this may be a false assumption. In the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick ignored Clarke’s description in his novel of how food was provided and eaten, with the almost humorous showing of liquid foods with flavors served to Heywood Floyd on his trip to the Moon.

Still from the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. The flight attendant (Penny Brahms) is bringing the flavored, liquid food trays to the passenger and crew.

Because the Moon does not have terrestrial day-night cycles, the food was single-celled and likely grown in vats, then processed to taste like the foods they were substituting for.

Michaels: Anybody hungry?

Floyd: What have we got?

Michaels: You name it.

Floyd: What’s that, chicken?

Michaels: Something like that.

Michaels: Tastes the same anyway.

Halvorsen: Got any ham?

Michaels: Ham, ham, ham..there, that’s it.

Floyd: Looks pretty good

Michaels: They are getting better at it all the time.

Still from the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. Floyd and the Clavius Base personnel select sandwiches made from processed algae. Above is the conversation Floyd (William Sylvester) has with Halvorsen (Robert Beatty) and Michaels (Sean Sullivan) on the moon bus on his way to TMA1.

This is where food technology is currently taking us.

Single-cell protein has been available since at least the 18th century with edible yeast. Marmite or Vegemite is a savory, yeast-based, food spread that is an acquired taste. Today there is revived interest in various forms of SCP, some of which are commercially available for consumers, such as Quorn made from the micro-fungus, Fusarium venenatum. The advantage of single cells is that the replication rate is so high that the raw output of bacterial cells can be more than doubled daily. The technology, at least on Earth, could literally reduce huge tracts of agricultural land use, especially of meat animals. However, it does require all the inputs that hydroponic systems require, and further processing to turn the cells into palatable foods including simulated meats. Should such single-cell food production become the basic way to ensure adequate calories and food types for settlers, I suspect that real food will be as desirable as it was for Sol Roth and Detective Thorn in Soylent Green.

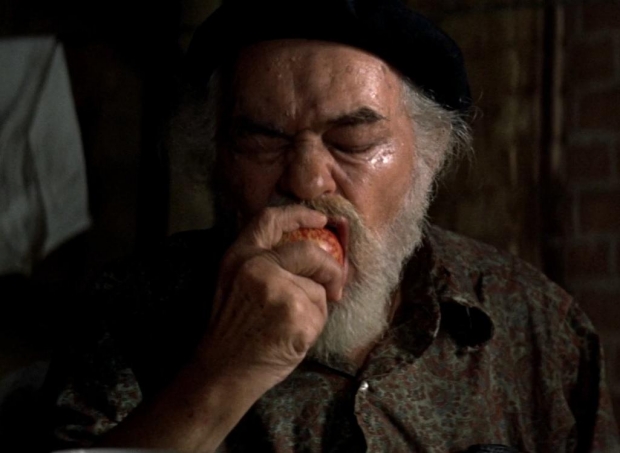

Still from the movie Soylent Green. Sol Roth (Edward G. Robinson) bites into an apple, stolen by Detective Thorn (Charlton Heston), that he hasn’t tasted in many years since terrestrial farming collapsed.

Physical and Mental Health with Soil

However, even if single-cell bioreactors, food manufacturing, and hydroponics do become the main methods of providing food, that does not mean that creating fertile soils from the regolith is a waste of effort. Surrounded by the ochres of the Martian landscape, the desire to see green and vegetation may be very important for mental health. Soils will be wanted to grow plants to create green spaces, perhaps as lavish as that in Singapore’s Changi Airport. Seeds brought from Earth are a low-mass cargo that can exploit local atoms to create lush landscaping for the interior of a settlement.

Changi Airport, Singapore. A luxurious and restful interior space of tropical plants and trees.

There is a tendency to see life on Mars not just as a blank canvas to start afresh, but also as a sterile world free of diseases and other biological problems associated with Earth. Asimov’s Elijah Bailey stories depicted “germ-free” Spacers as healthier and far longer-lived than Earthmen In their enclosed cities. We now know that our bodies contain more bacterial cells than our mammalian cells. We cannot live well without this microbiome that helps us withstand disease, digest our foods, and even influence our brain development. There is even a suggestion that children that have not been exposed to dirt become more prone to allergies later in life. Studies have shown that most animals have a microbiome with varying numbers of bacterial species. As Mars is sterile, at least as regards a rich terrestrial biosphere, it might well make sense to “terraform” it at least within the settlement cities. Creating soils that will become reservoirs for bacteria, fungi, and a host of other animal species will aid human survival and may become a useful source of biological material for the settlers’ biotechnology.

If Mars is to become a second home for humanity, it will need more people than the villages and small towns that the historical migrants to new lands create. The needed skills to make and repair things are vastly larger than they were less than two centuries ago. Technology is no longer limited to artisans like carpenters, wheelwrights, and blacksmiths, with more complex technology imported from the industrial nations. Now technologies depend on myriad specialty suppliers and capital-intensive factories. Mars will need to replicate much of this in time, which requires a large population with the needed skills. A million people might be a bare minimum, with orders more needed to be largely self-sufficient if the population is to be the backup for a possible future extinction event on Earth. Low-mass, high-value, and difficult-to-manufacture items will continue to be imported, but much else will best be manufactured locally, with a range of techniques that will include advanced additive printing. But some technologies may remain simple, like the age-old fermentation vats and stills. After all, how else will the settlers make beer and liquor for partying on Saturday nights?

References:

Kokkinidis, I (2016) “Agriculture on Other Worlds” https://centauri-dreams.org/2016/03/11/agriculture-on-other-worlds/

Kokkinidis, I (2016) “Towards Producing Food in Space: ESA’s MELiSSA and NASA’s VEGGIE”

https://centauri-dreams.org/2016/05/20/towards-producing-food-in-space-esas-melissa-and-nasas-veggie/

Kokkinidis, I (2017) “Agricultural Resources Beyond the Earth” https://centauri-dreams.org/2017/02/03/agricultural-resources-beyond-the-earth/

Higgins, A (2022) “Laser Thermal Propulsion for Rapid Transit to Mars: Part 1”

https://centauri-dreams.org/2022/02/17/laser-thermal-propulsion-for-rapid-transit-to-mars-part-1/

Balk, M. (2008) “(Per)chlorate Reduction by the Thermophilic Bacterium Moorella perchloratireducens sp. nov., Isolated from Underground Gas Storage” Applied and Environmental Microbiology, Jan. 2008, p. 403–409 Vol. 74, No. 2

https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/AEM.01743-07

Coates J.D., Achenbach, L.A. (2004) “Microbial Perchlorate Reduction: Rocket-Fueled Metabolism”, Nature Reviews | Microbiology Volume 2 | July 2004 | 569

doi:10.1038/nrmicro926

Hatzinger P.B. &2005) , “Perchlorate Biodegradation

for Water Treatment Biological reactors”, 240A Environmental Science & Technology / June 1, 2005 American Chemical Society

Kasiviswanathan P, Swanner Ed, Halverson LJ, Vijayapalani P (2022) “Farming on Mars: Treatment of basaltic regolith soil and briny water simulants sustains plant growth.” PLoS ONE 17(8): e0272209.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272209

Gilster, P “Spacecoach: Toward a Deep Space Infrastructure“, https://centauri-dreams.org/2016/06/28/spacecoach-toward-a-deep-space-infrastructure/

Davila A.F. et all (2013) “Perchlorate on Mars: a chemical hazard and a resource for humans” International Journal of Astrobiology 12 (4): 321–325 (2013)

doi:10.1038/nrmicro926doi:10.1017/S1473550413000189

Monbiot, G. (2022) Regenesis: Feeding the World Without Devouring the Planet Penguin ISBN: 9780143135968

“If Mars is to become a second home for humanity, it will need more people than the villages and small towns …”

it needs more than people to make a village – it will need a Hillary Clinton …

Since HRC will most likely be pushing up daisies by the time the Martian villages and towns are to be created, does that mean that the whole enterprise is going to be futile? ;-)

“…does that mean that the whole enterprise is going to be futile?”

if it (the whole enterprise) means its going be like her, then I’d have to answer : Yes.

Rust free wheat…trees to grow with no parasites. Dutch Elm…ironwoods?

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ironwood

To keep the base plants disease free, all the plant material will have to be sterilized on Earth before shipping, just as plants shipped to California from certain locations must be. This suggests that to be safe, seeds will have to be the principal imports, backed up with sterilized cuttings.

The biggest issue for me is that apart from wind pollination of grass crops, most crops we eat need insect pollinators. Will bees need to be included on the base, or will workers have to do the pollination with brushes? When you consider the effort, it may be that SCP is the easier solution.

How is pollination handled in greenhouses and vertical farms when growing insect-pollinated fruit like strawberries?

Plant multiplication material is NOT sterilized before shipped because in that case along with the pathogens you also sterilize the plant, which defeats the purpose. What you do is follow generally accepted phytosanitary protocols such as shipping the plant without the ball of soil its rooting system is in or washing it out and then planting in some mineral inert material. Also do actual molecular tests on the plant to see that it does not have any infections including fungi. There are also other system methods to reduce infectants, such as growing potatoes for multiplications in high altitude or windy places to ensure aphids, which would carry viruses, do not have a chance to infect the plant. Making sure that your multiplication material is pathogen free is an entire industry which is why between practices and certification a plant intended for multiplication is way more expensive than a run of the mill plant for your pot.

As for how pollinators are used in a greenhouse, well there are boxes of bees available for this purpose:

https://files.greenhousegrower.com/greenhousegrow/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Koppert-feature.jpg

You can buy them from suppliers. Be aware though, tomatoes can be multiplied parthenocarpically, but those sexually reproduced are way tastier, have seeds and are less succeptible to pathogens

What would be the issues of having bees in the Mars colony? Can they survive in the greenhouse atmosphere? Can they be kept out of the living areas and reliably confined to the greenhouses? Can the queen and drones be transported on the belong journey to Mars, or will it require a colony? Like plants, it will be important that the bees are disease free when imported. At least bees can only reproduce with a queen and male drones, so it is unlikely that a new colony will appear where it isn’t wanted.

Bees have flown in space and the have been able to function decently in microgravity. Otherwise all I can say is that we will uncover what are the issues when we get to Mars

Indoor vertical farming has shown that no soil is needed to grow crops. No Sun either, and here on Earth over 90% less space and water than traditional farms.

Can you elaborate on your “no soil” comment. Are you saying that vertical farms are using hydroponics, or some other approach to anchor the plants and provide nutrients?

If you want to grow grass crops like wheat, are there any examples of this being achieved in a vertical farm?

If you want fruit and nut crops, how would you grow trees in a vertical farm? Is there any efficiency to be gained from trees given their height?

It is my understanding that vertical farms work only for high-value crops to be delivered to local markets. The cost of building and operating vertical farms is very high, precluding most commodity crops. For a Mars colony, unless you can locally manufacture the structures and lighting, is there any advantage of going with the vertical farm approach over a more traditional greenhouse?

Though they contradict all common sense, there are remarkable results posted for vertical farms. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2002655117 According to that, wheat can grow 24 hours a day under constant light; they mention hydroponic or aeroponic root systems. Despite this, the capital and electricity costs, competing against farms that I think are now receiving about 40% subsidies, vertical farming isn’t profitable. Once the cost of pressure domes over vast fields is factored in, that changes. :)

https://www.agrifarming.in/profitable-crops-for-vertical-farming-a-full-guide suggests a height limit of about 30 cm for vertical farm crops. But according to them NASA is the agency that pioneered aeroponics and vertical farms for space exploration in the first place, so I bet they can invent a clever way to stack up apple and almond trees if someone gives them a mission of sufficient duration.

In my garden, I have both a lemon tree and a lemon “bush” (ie a very small tree that tops out at 6 feet but has its lower branches just above the ground). I suspect the best way to have fruits and nut trees is to breed/engineer varieties that are small, possibly ground-hugging. That would allow stacking if desired, and certainly easier to harvest by hand or robot. Perhaps just careful pruning is the way to go, for example creating espaliers as was done in Europe when the climate was cooler.

I don’t foresee redwood trees growing on Mars unless it is terraformed (a very expensive, long-term project), so lumber cut from tree trunks seems very unlikely. However, engineered wood from wood shavings from woody shrubs and small trees may be present. OTOH, maybe realistic lumber, or at least veneers, might be 3-D printed from cellulose and lignin.

Bamboo laminates would be a good option for Mars, if they wanted “wood”.

There is also hemp to make furniture and building materials.

Not to mention pharmaceuticals; for export only, of course!

They could call it Mighty Martian Maroon.

This is a very good article and I like the references to my essay here from a few years ago. Here are though a few comments, with numbers for reference:

1. The fundamental purpose of animals in a farming system is to convert food sources that are not palatable to humans into sources that are. It will be a while for cows, pigs and chickens, especially since poultry may even fly on Mars gravity. Have you thought though of rabbits? Small, reproduce quickly, do not take much space. As for squeamishness, well, you relatives in the villages do things that are quite squeamish to urban folks and vice versa. The typical American food model with meat in all three meals a day and even in a few snacks inbetween beyond being atypical and unhealthy is simply unsustainable on Mars because Mars does not have the large ranges that the US has where plant culture is hard to impossible. As recently as the 1950s in Greece meat was something the typical family ate on Sunday at best, assuming that it was not lent. I have always assumed that a Martian diet would look like that.

2. Hydroponics far predates electronics. Electronics failure will simply means that you will need to put up some alarm clocks to turn on and off the fertigation lines. But yes, it does require more care that plain soil based agriculture

3. For soil remediation there is a panacea: it is called compost. You can create it quite easily by co-composting biosolids, in other words what comes out of the water treatment plant, with hard plant material such as corn stalk. Leave in a place with good aeration for 45-60 days overturning it a few times. Alternatively what come out in the root bags after you have harvested pleurotus mushrooms, or most mushrooms for that matter, is a soil amendment on its own. No need for fancy bioreactors or reverse osmosis for soils, though osmosis may be necessary for water. After washing out regolith just mix what is out there with soil compost and you have ready to use mineral soil. At your nearest land grant college there is at least one professor which specializes in soil remediation and they have most likely already treated something far more toxic than washed Martian regolith.

4. Cover crops are for the American/North European growing cycle of planting in the spring and harvesting in fall. As a south European it made no sense in me until I came to this country, nothing can really grow unirrigated in a Mediterranean summer. As for soil organic content, no need for that kind of treatment. In the old world there are fields that have been farmed for some 10,000 years now that are extremely low in organic matter. Plants do grow there, so long they get their nutrients

5. A small emendation: inside a Martian greenhouse there will be the illumination of North Europe, i.e. North of the Alps. Think something like Amsterdam, not Ierapetra. End result we can plan for a greenhouse than looks like one from Amsterdam as opposed to one from Ierapetra.

6. In the USSR and its successor states local government (think region to county level) maintains a standard farm where they practice agriculture without any chemical inputs, such as fertilizer, which is then compared with what is grown in actual farms to see how many times the standard farm they can achieve and thus evaluate the farms. Low to no input extensive agriculture also means far higher area is needed plus crop rotations and no crop grown every 3-4 years so as to help the soil recover. Also polyculture like the three sisters of the Americas. Honestly it is a balancing act, what is easier, have fertilizers or have 4-5 times the area under agriculture?

7. What is grown on earth depends on pedoclimatic, financial and economic factors. It is not so much that soil A is good for crop 1 but not for crop 2 and soil B good for crop 2 but not 1 though there are exceptions, most importantly tobacco which grows best in bad soils and rice that needs flooded soils most other crops can’t grow. It is more like in soil A crop 1 will produce $10/1000 m^2 and crop 2 $8/1000 m^2 while on soil B crop 1 will produce $3/1000 m^2 while crop 2 $4/1000 m^2. A good soil is good for all crops and I would refer you to your state’s soil yield database such as Virginia’s VALUES or North Carolina’s RYE. In Mars where we will need to provide all inputs, it is a different calculation

8. So far it is not known how much single cell protein is safe to eat for a human or even an animal. SCP has proven too expensive compared to field grown crops for this sort of experiment so far especially since the funding agencies e.g. USDA-NIFA are not funding this kind research. We definitely need someone to fund this kind of research

Please do not take my comments as a take down, I really enjoyed this article.

Thank you for your kind comments.

Meat is not just to convert unused plant material. That can be done by fungi. Meat historically is a very energy-dense food, great if you are hunting or live where plants are rare, such as the Arctic.

I don’t envisage Martian crops grown in a Mediterranean climate. The med is too dry in summer. [I also read many years ago that there was evidence that the Ancient Greeks exhausted their soils and had to move their farms, much like early American cotton farmers.] If you have a greenhouse, you can create almost any climate you like. Kew Gardens in London has a set of joined greenhouses that recreate a number of terrestrial biomes, as does, I think, the Eden Project in SW England. More to the point as you note, soil conditions will also determine suitable crops. So poor dry soils will support millet, while flooded soils are needed for rice. Neither crop would grow in the other’s soil.

SCP (as cultured meat cells rather than bacteria) is already sold in Singapore and is expected to be sold in the US soon. My guess is if there are problems, they will be subtle and not known for years. Similarly, processed yeast cell has been available as Marmite/vegemite since before I was born. Yeast cells are still alive in home-fermented alcohols, so they are safe. IIRC, BP’s SCP from bacterial using methanol as a feedstock was not going to be allowed for human consumption because of the methanol, but not the bacteria. Given our knowledge of the microbiome, I would guess that carefully selected strains of bacterial species will prove safe, especially if the product is processed to ensure that the cells are dead or destroyed. We can always feed new varieties to animals if we are unsure of their safety, even if that defeats the purpose of their use to reduce grazing land and CO2 emissions on Earth.

What does seem self-evident to me, is that space limitations will force Martian farming of traditional crops to be very intensive – polyculture, multiple harvesting – and likely highly integrated with waste management to recycle nutrients. But I could be surprised if it turns out that cultured cells in bioreactors and then processed to look and taste like traditional foods are possible and utilized on Mars to avoid space and labor used to grow crops. Maybe real foods are grown in pots in living quarters as a speciality treat or gift, as oranges once were in Northern Europe. [Do orangeries still exist now that they can be easily transported in bulk from where they are grown?]

“I would guess that carefully selected strains of bacterial species will prove safe, especially if the product is processed to ensure that the cells are dead or destroyed. ”

I am NOT going to (knowingly) increase my daily alotment of specially selected strains of bacterial species; whether cells are dead or destroyed.

You ingest bacteria with your food whether you know it or not. Where do you think your microbiome comes from? The trick is to avoid pathogens that can make you very sick.

Interestingly enough, microbiome modification by ingesting cell cultures already exists.

There is also snails which would eat waste organic material. Also there are parts of Mars that offer magnetic protection I believe almost as strong as the earths.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Schematic-of-the-solar-wind-interaction-with-Mars-from-Brain-et-al-2015-The-solar_fig2_285393397

“You ingest bacteria with your food whether you know it or not. ”

I said knowingly…

I can accept than a Martian settlement of 10,000 people will not have animals grown for meet, but not a settlement of 1,000,000. I know that I am opening a can of worms here because people have strong opinions about food, but plant food and animal food is not the same. Beyond the low hanging fruit such as Vitamin B12 which cannot come from plant based sources there is the issue that even if their nutrients belong to the same category they are not the same. For example the protein of reference for human nutrition is albumin, which is egg protein. You can get proteins from plants too, but pea protein does not have the same nutritional value as albumin. Veganism is more of a 20th century thing and before the abundance of a variety of nutritional sources that modern trade brings practicing often meant a rather short and unhealthy existence. My philosophy has always been ??? ?????? ???????, in other words Everything in Moderation which is attributed to the (tyrant) Cleobulus of Lindus, one of the Seven Sages of Ancient Greece. Yes, fungi can also break down hard material, yes they can provide some nutrition but a long term balanced diet does require animal sources.

Plants inside a greenhouse are grown preferably in their optimum environment, at least as much as the general environment allows. Plant A will grow better at something like 15-25 C (degrees Celsius) and will survive without growth say 5 C. However economically it does not make sense to have the heater on permanently at night to keep the plant at 15 C, you will keep it at 5 C and let the temperature rise during the day. Also once it gets to 25 you start opening windows to allow it to cool off and new CO2 to enter. We will not be seeing on a Mars greenhouse 40 C in the summer and 40% humidity, sure an olive tree can survive that but it is not its optimum and is not very productive under these conditions. Also it is cheaper to heat a greenhouse from the 0 C which is the maximum Mars gets in its equator to 20 C rather than 40 C.

My comment about feeding animals SCP has to do with that usually we first test new food on animals before the give to humans. Someone needs to fund studies where animals are fed SCP as a high proportion of their diet before advocating that people eat SCP as a high proportion of their diet. There was a study in late December 2022 that made the news where Dutch researchers analyzed all vegan sausages in the Dutch market, I no longer remember if they also fed them to animals or people. With the exception of tempeh based sausages, the metals in their content, meaning Fe and Zn if I remember correctly, were not bioavailable because they became bonded to phytase. Tempeh did not have that problem because the phytase had been reduced though the fermentation that created tempeh. I do eat the meat substitutes available in Fresno when it is Lent, we are not there in taste compared to what they are substituting and nutrition wise also we are not there.

It is pretty well known among soil scientists that with the exception of river valleys all ancient soils have been exhausted to eroded due to millennia of agriculture. We did go up Mt Parnitha when on a field trip as an undergrad and we were shown a soil formation that can only form under a meter of soils that was exposed to the surface because of erosion after 6 millennia of agriculture. We were also shown pictures from Spain and Portugal where after three centuries of intensive agriculture the field had been reduced to an O-R horizon so they abandoned agriculture and took up silviculture because it was impossible to grow row crops any more. This, along with phytosanitary reasons (when you grow in the same greenhouse the same crop constantly pests get out of control) is why hydroponics was adopted in the 1960s in large scale staring in the Netherlands.

I thought that was a myth. I know very healthy adult vegans. One definitely doesn’t was to make a developing child vegan, but once adult, that is no longer an issue. It may require some extra vitamins like B12, but AFAIK veganism is not a health problem.

In principle, I would agree with you. However, other new foods are introduced without animal testing. However, it reminds me of the attempts for Britain to find alternative food sources during WWII when German U-boats were making food imports very difficult. Marine zooplankton was harvested with an innovative net. The cooked zooplankton was fed to rats in increasing fractions of their regular chow. Apparently, once the ratio got to around 30%, the indigestible chitin exoskeletons clogged up the rats’ intestines. That was definitely a case of animal testing being needed before the food was foisted on the general public.

Last time I was in Mt Athos in the summer of 2022 I was told the story of a monk who during the German occupation, that would be WWII, developed tuberculosis and was told by the doctors to start drinking milk. He left for Ouranoupolis where he started consuming dairy- the diet of Orthodox monks is vegan to pescatorian, and did get better. I am pretty sure that you know many healthy vegans, especially today that we know what constitute a healthy diet molecularly, what are the necessary elements you need to get and there is a global supply chain to provide them for various sources. Also note we live in relatively fair weather conditions in terms of health, COVID 19 is the first pandemic in a century as opposed to the early modern period where there was a plague epidemic once a decade between the black death and the 18th century. Every new environment people live in brings about new discoveries that we did not know off. For example that human shed so many skin cell constantly was not known until it was discovered in the closed environments of submarines. Also much as evolution is not static and does not have an end point, it is certain that modern innovations often run into unexpected demands from our bodies. The sedentary office life is comfortable, but our body does need to exercise which is a why you are healthier if you go to the gym regularly. I am fully aware how the genes that allow adults to process dairy are associated with people of origins where diary animals were domesticated and just how many lactose intolerant people are out there. This is why I am willing to err on the conservative side, let’s try to eat everything people on earth eat than remove something and try to see if it is really necessary. There will be Martians that will want to eat meat and not just the easier to grow mealworms and snails just as there are many Norwegian Americans that want to eat lutefisk for cultural reasons, even though the description I have is that it is barely palatable to American palates.

Future Martians will need to make sure that are getting enough protein, for example, rice and beans which eaten together give you a complete protein source.

Lettuce and alot of other vegetables provide variety and vitamins , but are largely water and cellulose.

A non animal protein, similar to yeast, is a naturally occurring fungus called fusarium venenatum (commercially known as Quorn)…

And dont forget the wide range of mushrooms which dont require light to grow.

However, consideration should probably be given to bringing chickens.

1) they produce eggs, which provides a periodic repeatable source of high quality protein, instead of a one time butchering like pigs, cows, rabbits, etc.

2) they’re fairly compact

3) even in low light levels of winter some breeds continue to lay

4) they’re great at recycling scraps

5) theyll eat stuff you may find distasteful like meal worms, crickets, etc.

6) their waste provides a high quality manure for crops

It appears that there are large expanses of permafrost on mars. Liquifying that water would potentially provide a habitat for any number of seafood, including cold water tolerant fish. I cant help but be reminded of the ocean life living under the ice caps.

Regarding light sources, I think Id feel safer with reflective surfaces concentrating the light. They’re lower tech, unlikely to fail, and probably far easier to manufacture on site than LEDs.

“Regarding light sources, I think Id feel safer with reflective surfaces concentrating the light. They’re lower tech, unlikely to fail, and probably far easier to manufacture on site than LEDs.”

The only issue would be dust storms sticking dust to the reflectors but there should be ways to clean them automatically. As for LED’s they could be used to boost needed frequencies of received light. Fungi offer a good source of proteins and can grow in cold weather.

https://nph.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00177.x

And can be used to make clothing.

The material is made in a process called bio-fabrication which means it’s grown in a lab. Fungi root system, called mycelium, is being harvested for the process. The result is a leather-like material that can be used for both clothes and furniture’s.

See my comment lower down regarding reflectors. I think we are in broad agreement.

Fungi will likely be an important part of the soil production process, although mushrooms may be a specialized part of the food crop. As for using their structures for clothing manufacture, that is possible. IDK of any fungal fabrics on the market currently – it is mostly research material AFAIK. Plant fibers are far more established, and bamboo can be used for a range of manufactures from cloth to flooring. Gene-engineered organisms can be used to make synthetic silk, and I wouldn’t rule out synthetic fibers either. Weaving machines are lo-tech so any process that can make long fibers that can be spun into thread and woven could be present on Mars. Given the likely shortage of goods, I would expect the need to display individuality may be expressed in clothes, fabric colors, and designs. What I don’t expect is cotton growing, or sheep rearing for wool. Without large animals like cows, there will not be leather, although leather substitutes may be available.

What we should be wary of is visualizing Martian settlers as in any way similar to those in North America, especially the American West. If anything, it may be more like the more dense populations of India, North Africa, Indonesia, and China, but with much of the architecture below the surface, yet still crowded, with food smells and a distinct “Martian” culture developing to meet the needs of that environment. Independent miners and farmers seem unlikely in such a harsh environment that will need lots of help from others to survive.

As a building material.

https://happho.com/an-emerging-sustainable-construction-material-mycelium-bricks/

As clothing

https://www.labroots.com/trending/earth-and-the-environment/3587/mushroom-made-twist-clothing

Also perhaps the Martian moons would be of value with minerals which can be dropped down to the surface.

The technology we live with and available to the settlers might be as much of a handicap as a benefit. I often think that more primitive technologies might be better for survival, simply because they can be repaired with simpler methods and therefore less reliant on manufactured imports. farmers in the 1940s US that seem to be what Heinlein envisaged as colonists, might be a better bet than modern agronomists requiring electronics and computers. No-one is farming outside on the surface, it will all be inside. It is possible farming with not happen at all, with food being produced from cell growth and processed to mimic foods we eat, or perhaps more like the biscuits in “Soylent Green”. Would we even bury the dead, rather than recycle them? My post is about options and considers other issues beyond foods as nutrients.

Clever and inventive use of local resources will be an important skill on Mars, much as it is in any relatively isolated settlement. Unlike earth, there is no indigenous macroscopic life to exploit, just a mostly sterile, rocky surface, and whatever can be cultivated from seeds and eggs. Wood, for example, would be the rarest of materials, and therefore an extravagant luxury import, even after a generation when some trees have reached maturity to harvest.

While I would want to visit the Moon and, given time, Mars, I wouldn’t want to live there. Mars will be a harsh place to live, and very limited and constraining, despite the apparent unexplored surface.

“Would we even bury the dead, rather than recycle them?”

While recycling of bodily waste and, in fact, pretty much everything else is likely to be an essential part of a functioning Mars colony, I still have doubts that loading dead bodies into a recycling plant is likely to be considered acceptable.

Mind you, strictly speaking burial *is* a form of recycling. While cemeteries are not usually considered suitable places to grow crops, most do have trees and gardens, which presumably benefit from extra nutrients provided by the inhabitants…

On Mars, I’d imagine cremation is likely to be considered both acceptable and efficient, with the ashes scattered on green places – a practice common enough here on Earth.

Soil from cemeteries is particularly fertile. Very useful where the soils can be poor.

I agree that Martians will not likely want their bodies tipped into a recycler. OTOH, the culture may differ. Think of the fictional Fremen recycling to extract the water from the dead in Dune.

There are/were different burial methods on Earth, and a new one is eco-burial to prevent the use of fossil fuel-powered cremation. If carbon fixation on Mars is easy, then cremation may be the method of choice. OTOH, if soil manufacture is hard, then maybe burial in special soil-making pits might be preferred. I suspect it will all depend on culture and resources as to the method[s].

Reflective surfaces will need the equivalent of feather dusters and/or pressure hoses to periodically clean off accumulated dust.

I think chickens would be a useful farm animal on Mars for a few reasons

– they turn insects and scraps into eggs

– their droppings are useful fertilizer

– in the low gravity of Mars, they could fly, which I think they would enjoy

Also, I would say that artificial fertilizers will be heavily used in the early days at least. It’s a well-understood technique and Mars will need a mature chemical industry anyway.

They like too scratch the ground up so would help mix up the soil and birds can live in lower pressure enclosures than humans due to their higher efficiency lungs.

Chickens, like other animals, will need to be managed on the months-long journey from Earth. Even starting with fertilized eggs most of the journey will require managing adult birds. As for food, I do not envisage insects as being freely available in the Martian base. Any escapees from food-producing areas will likely be eradicated as fast as possible. They certainly won’t want pests, especially cockroaches. If chickens are present, settlers may have to be vetted for allergies to chicken feathers, as there is no escape from the allergens.

If Mars is to use fertilizers, it will need the infrastructure to support production, especially of nitrates. Yet more mass to transport, and initially bringing sacks of fertilizer on the ship seems unlikely to me. Better to avoid such fertilizer as much as possible, IMO.

It takes around 21 days for the egg to chick cycle, we could send the eggs on an express rocket after all there is no big infrastructure need for their journey upkeep. They could be housed in a lava tube setup with part LED lighting with lower pressure enclosure requirements which substantially reduces the building structures.

What “express rocket are you speaking of? You seem to imply that there is one in the wings that can do the Mars run in less than 21 days. I know of no such ship, although the “Wind Rider” can be inferred to have that sort of mission time. If we can get such short delivery times to Mars, a lot of opportunities open up.

The payload would be quite small and if attached to a very powerful rocket it could get to mars quite quickly, 21 days is rather fast though. But there are other birds with longer incubation periods of up 80 days such as the albatross and ostriches at around 50 days.

It would be terrible if on arrival, the eggs were all broken and all that was left was a lot of dead chicks just prior to hatching. The developing chick embryos still need life support as the egg shells require gas exchange. Unless O2 is provided, and waste CO2 vented, the embryos will suffocate. I don’t raise chickens, but don’t the eggs need turning in the hatcheries? Is gravity important for embryo development?

Perhaps spin stabilisation of the craft to provide a small amount of g forces. Eggs do not require a lot of air and upkeep and we could quite easily do some experiments on earth.

https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2015/11/16/goats-on-boats-a-u-s-navy-tradition/

Don’t count goats out. They used to be common on sailing ships. Can eat anything and adapts well to life at sea. One goat apparently sailed around the world with Captain Cook. If any animal can survive a trip to Mars a goat can.

Slow cooked old goat curry anyone? Special dish served every First Landing Day

Saved but for the smell of these lovely creatures.

That might be part of the social or justice system.

Drunk & disorderly? 30 days mucking out the goat pens after your regular work shift. Teenagers need to spend a year helping on the farms including the goat pens.

Martian lava tubes could be a good place to grow crops with a mirror system to send concentrated sunlight down through them. The amount of water on Mars in ice beneath the surface could be used to create lakes in these 3000 to 10,000 foot diameter lava tubes on Mars. Could the soil underground be better then surface soil?

https://www.cnet.com/science/scientists-find-mars-lava-tubes-could-be-roomy-habitats-for-humans/

https://www.universetoday.com/147360/lava-tubes-on-the-moon-and-mars-are-really-really-big-big-enough-to-fit-an-entire-planetary-base/

I favor reflective surfaces over light modules for the manufacturing issue. However, reflective plates, whether glass or metal will be both covered in dust and need regular cleaning and abraded reducing their reflectivity. Extended dust storms reducing light levels cannot be avoided by this method. Pragmatic settlers may use both mirrors and lighting. Surface greenhouses don’t need lighting when the sky is clear when sited near the equator, as light levels are similar to those in Northern Europe. But the trade off is increased radiation exposure, not just for the crops, but any human worker in the green house.

Lava tube living solves the radiation issue, but then lighting must be provided by reflectors through ports, and interior lighting. Without views, living underground can be oppressive. Martian settlers might complain that they have come millions of miles to live in a new home with “room to breathe” but are stuck in a dark tube. In any case, the limited number of tubes means that the growing population will either need surface structures or create subsurface living and working areas. Jablokov’s “River of Dust” novel depicts a Martian civilization that has built underground cities. I don’t recall the novel explaining how food is grown. The same food supply issue is found in McDonald’s “Luna” trilogy, where the lunar cities are underground, but there seems to be no mention of any ag areas. Food production must be entirely synthesized from unicellular organisms. Real coffee is extremely expensive and imported. Most lunarians drink mint tea.

As for the soil issue, I have no idea. The regolith, if any of the tube floors, should be almost perchlorate free. However, the inside of the tubes may be just solid rock, and possibly very hard rock. Without exposure to impactors and day/night fracturing, ,there will not be any regolith to collect as the basis for soil production. This doesn’t stop settlers from bringing regolith into the tubes, but then it will be contaminated with perchlorates.

Easy way to get around the dust problems is put the mirrors in orbit. 2 mile across lava tubes 100 miles long with 1000 feet deep lakes. Dust stormd effect everyone no matter where they are at

except below ground.

Even orbiting mirrors cannot push sunlight through the dust storms. A storm weeks long will keep the surface quite dark for during this time. As long as the storm doesn’t last months, the plants may be fine as long as they are not cooled. However, if they are integral to ECLSS O2 production, that could be an issue.

KSR’s Mars trilogy had solettas in orbit to help with the terraforming project. Orbiting mirrors have been proposed to illuminate cities at night, but how do you position them to illuminate the daytime? [This is different from ground-based mirrors.] Is the solution to reverse the day/night cycle for the ag areas?

Looks like another problem with surface based crop production;

Influence of Martian Radiation-like Conditions on the Growth of Secale cereale and Lepidium sativum.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fspas.2021.665649/full

The Fact and Fiction of Martian Dust Storms.

“Once every three Mars years (about 5 ½ Earth years), on average, normal storms grow into planet-encircling dust storms, and we usually call those ‘global dust storms’ to distinguish them,”

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/the-fact-and-fiction-of-martian-dust-storms

The dust storms will not damage ground bases mirrors according to the article, they just need to be cleaned off or covered during the storm.

As for living in an environment on the surface a giant lava cave would be able to develop a complete close ecosystem of plants, fish, shellfish, worms etc… that we do now on earth based aquamarine systems or Aquaculture ponds. https://www.examplesof.net/2018/09/10-examples-of-artificial-man-made-ecosystem.html

Large ground based metal mirror systems do not need the accuracy of telescope mirrors and multiple concentrators of sunlight could be routed above the ground near the roof of the cave for miles and directed down to illuminate below. Gravity on Mars is only 38 percent of earth so infrastructure projects would be much easier to build. The Martian surface has a large number if nickel/iron meteorites on its surface plus many more asteroids coming nearby from the asteroid belt. Surface based and space based production of raw materials with 3D Printing Machines producing metal products.

Plenty of ice…

Elsewhere I have suggested that ice would make both a good, but light transparent, radiation shield and a suitable mass to relieve the pressure on the surface greenhouses from blowing out.

Elsewhere I have discussed the issue of radiation in unprotected ag areas in surface greenhouses. [OGH, PG, has suggested that this article will be posted on CD.]

Good to hear that dust storms will not abrade surface mirrors, although I await actual experience to confirm that. Surface mirrors will be a lot easier to manufacture and reorient with the sun to maintain the light tunnel being illuminated. But again, they will not be useful during these global dust storms, and as Ioannis has indicated, Martian illumination levels around the equator are not that different from those experienced in greenhouses in Holland.

As Robin has suggested that a feather duster could be used to clean the mirrors, I will try StableDiffusion to paint an image of a robot dusting a mirror on Mars.

According to https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328319061 the hardness of Martian dust is only Mohs 4.3, so I think you shouldn’t even need special glass to avoid abrasion. So far as I know the problem with Mars rovers is simply that there is no one to wipe the panels off. I don’t understand why NASA hasn’t worked out a solution, whether it be something as simple as a windshield wiper or electrostatics, or some new technology. Given recent impressive advances in acoustic holography ( https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abn7614 ) … I wonder if engineers could place an array of acoustic transmitters on solar panels or reflectors so that the main force of the entire array can be focused to raster scan the entire surface, systematically cleaning away the dust without macroscopic moving parts.

There was a paper saying that supplementary wind power can help to cover gaps in solar availability. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-022-01851-4 It will also be interesting to see if some recent suggestions of ongoing geologic activity can lead to sites where geothermal (nay, areothermal!) energy is an efficient option.

Interesting, since the area around Cerberus Fossae region has had recent floods and geothermal activity. The nearby Elysium Planitia and Elysium Mons volcano looks to have a high number of lava tubes. Wind power makes sense and abundant humans to fix any problems. The big three, solar, wind and geothermal plus the indications of large supplies of underground water/ice make this a good place to set up camp.

Recent aqueous floods from the Cerberus Fossae, Mars.

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2001GL013345

Magma on Mars likely, study finds.

https://phys.org/news/2022-10-magma-mars.html

InSight locates marsquakes in the Cerberus Fossae region.

https://www.dlr.de/content/en/images/2020/1/insight-locates-marsquakes-in-the-cerberus-fossae-region.html

Fossae: long, narrow, shallow depressions

Cerberus: The three-headed watchdog that guarded the entrance to Hades. Cerberus was the child of a giant and a half-woman/half-snake.

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/images/pia06842-cerberus-fossae

Close to the Martian equator for good solar illumination…

In order to grow things on other worlds, we’ll have to live there for a long time just to learn how.

But we’ll not ne able to live there for any length of time unless we have an established agricultural technology and lots of experience under those conditions.

There is a chicken and egg issue, I agree. In practice, I think prepackaged food supplies will be the mechanism to feed the settlers until local food production is working. At this time, the favored method is hydroponics, as Ioannis deftly explained in his article and much of the Mars Underground work seems to suggest. But there is the issue of expansion, and this is where other approaches may be used and which I highlight in the OP.

The point is, do we need to go through all this trouble? Sure, it may be good for survey crew morale to have the occasional fresh salad with their frozen food concentrates, but there is really no need to have a permanent base there requiring a full-fledged agricultural establishment and the enormous investment, research and support that would require. Even here on earth, with our advanced agricultural science and millennia of accumulated experience, crops still fail and farmers still go broke. Too many things can go wrong for us to bet the lives of a survey team on the success of a farm where we never had one before.

I can see the potential need for a semi-permanent scientific base on Mars, like we have in Antarctica, but these attempts to colonize another world are a waste of time and effort. We already have a viable planet with plentiful under-utilized stretches, like the ocean basins and the polar regions and vast expanses of desert. We have the capability to settle these places now, although I doubt we could do so in away that produced more resources than it consumed. If you have to make your own air and water and chemically stabilize the soil so it isn’t poisonous, it becomes a fantasy, not a future. Even on our own remote terrestrial artificial habitats, like military bases, offshore rigs, mines in remote places, or scientific observatories, we have to bring in almost everything we need to survive by sea and air.

We live on a perfectly hospitable planet, one which is much more productive than any environment we could hastily devise in vacuum. If we should pollute the earth so badly we were forced to leave it, we would not have sufficient earth-generated resources to build and maintain space settlements until they became self supporting. And if they should ever become necessary, for whatever reason, putting them at the bottom of a gravity well makes no sense.

The space groupie colonization fantasy is like the sci-fi terraforming fantasy. Its not impossible, it is just unnecessary .

If our population is confined to Earth, then there will be fairly finite limits to economic growth, limits that we will reach fairly quickly even would all the necessary changes to avoid a climate and biosphere catastrophe.

What that means is that human expansion into the galaxy is effectively “off the table”.

Mars is certainly not the best 2nd home for humans. If we could build large O’Neill space habitats, that may be a better solution, even if each habitat has a hull surface area no greater than islands, and certainly not content or world sized. Building the habitats with multiple interior levels like the fictional “Babylon 5” makes more sense, and technology can create substitutes for views of the interior, like the Venice Casino in Las Vegas. Alternatively, robots could be the spacefaring economic entities to expand the terrestrial economy, but then wouldn’t they be the best colonists in the galaxy for the same reasons as humans not colonizing Mars?

It seems to me that traditional SETI almost assumes your position, with ETI limited to its home world, certainly not beyond its home system, and using em communication to reach other ETIs. KSR’s “Aurora” novel seems to be sympatico with the futility of living on even apparently suitable exoplanets, and that even an ecologically enclosed starship has a finite life span as the systems slowly degrade over time, implying space colonies are not the long-term solution either. All rather depressing for space cadets, especially poignant if it turns our life is rare and mind even rarer. As the conversation between Ellie Arroway and her father about ETI in “Contact” (movie version):

I’m certainly not opposed to the exploration of space or the expansion of our species; on the contrary, I support it and am willing to work for it. I just don’t think it will ever provide a home for our population in the event our planet is overcrowded, hopelessly polluted or threatened. I agree space may teach us much we may need to know, but no one is going to live “out there” except a tiny minority supported by the work and resources of the vast majority of those left behind. No “huddled masses yearning to breath free”, just a bunch of pampered technocrats who can afford the price of a ticket. A highly subsidized ticket, I might add.

That is an fundamentally elitist program, and I am opposed to it.

The problems of both industrial pollution as well as overpopulation have been largely solved without having gone to space. The purpose of going to space is not to flee a messed up Earth. Rather it is to have a frontier where any self-interested groups can go out on their own and have autonomy from political systems they do not share.

What concerns me is that space might become a place where toxic and malignant philosophies can go and fester, to nurture and perfect their social pathologies so they can force them on the rest of us.

Our own history of colonization here on earth is rarely about noble pioneers fleeing the oppression of the Metropole; its mostly about social misfits, predators and opportunists seeking the “freedom” to inflict their tyranny on others with total impunity, either the the wildlife, the natives, or their fellow colonists. My vision of the frontier isn’t hardy homesteaders, noble sodbusters and quaint churches, its ruthless cattle barons, greedy miners and endless water wars.

As for ” industrial pollution as well as overpopulation [being] largely solved “, well, I’ll not even bother to comment, let others make up their mind for themselves about that.. We may have the technical knowledge to address these problems, but those eager to cavalierly dismiss them

(or cheerfully export them to other worlds) are interested in no one’s political autonomy but their own.

Its no accident that techno-boosterism, entrepreneurial fantasies and authoritarian politics are so highly correlated.

I do agree that off-planet communities will lead to cultural diversity in the human species, something that seems to be quickly eroding on our crowded home world. But when its phrased in those terms, it may not seem quite as appealing.

This blogger seems to reflect your thoughts.

Against Mars: Space Colonization and its Discontents

Commenters on FB’s Mars Society group seem overly optimistic about the ease of Mars colonization. I partly blame Zubrin for this.

Enthusiasm is good, but there seems to me little realism about the difficulties, and an almost tech bro naivety about how humans behave. While I would expect that the mortality rate will be a lot lower than that experienced by the many that made the wagon treks across the North American continent to start farms, I don’t expect human nature will change that much to prevent the many social pathologies that were common in the absence of effective law enforcement. The US has only just made lynchings a crime, so it wouldn’t surprise me if Heinleinian summary judgments were made and executed by chucking unsuited people out of the airlock, as just one example.

Saadia is right so far as he goes. A Mars colony must be a technological achievement, and in our society technology is defined as what gives an elite who control it power over the commoners who do not.

Yet there is a larger context. If backward ideas might fester on Mars, they also fester on Earth. If technology destroys freedom on Mars, what can we say of each week’s news here, where science consists mostly of wearable sensors and trackable devices and enhanced AI threat analyses and every manner of surveillance?

If humanity does not belong on Mars, it also does not belong on Earth. The great powers play odds with nuclear war, and the people of the world ignore them, because they don’t know if that is the worst that could happen. Not when so many bright minds work on brain-machine interfaces and automated suppression of opinion.

Mars represents an escape – if not from Earth, then from thought, about the sad realities of humanity. A few outposts would pose little real risk of surviving to spread slavery to the stars. Perhaps they will discover something amazing. Perhaps one day the Fravashi will discover their ruins and run simulations of how the human race went wrong, such as the one we live in now.

“What concerns me is that space might become a place where toxic and malignant philosophies can go and fester, to nurture and perfect their social pathologies so they can force them on the rest of us.”

Thats not alays true; thats just propaganda that people drill into others for political purposes.

Q.E.D.

A Martian base should have some farm animals for sake of the ecosystem as well as practical uses. Parts of any farmed plant are inedible to humans, and that biomass needs to be recycled quickly into fertilizer. A very expensive mission with limited spaces for humans will not have room for cows soon, but there are other options; for example guinea pigs are widely farmed for meat in cramped environs, and could also be used in research or as pets.

The problem with farm animals is getting them to Mars. A trip of months, probably in micro-g will require careful management, not to mention food and oxygen. Large animals like cows seem highly unlikely. Rabbits a better chance.

Elsewhere a commenter stated that the Ancient Romans were able to ship large animals from Africa to Rome, so why not Mars. However, the trip time from Egypt to Rome by sea is far less than a trip to Mars, and the air is free. They also didn’t need to stay out of reach of land for feeding, except for the short hop from Tunisia to Scicilly, requiring only a couple of days to make that leg before they were in reach of places to load food. None of this is possible for the Mars trip as it stands, even with the fastest propulsion systems proposed.

On top of this, any crop failure results in having to cull your animals to try to feed the settlers. One doesn’t want to do this with a heavier animal like a cow or even a goat brought for milk.

So small mammals, fish, and invertebrates seem like the best bet. Going Vegan/Vegetarian might be the best option for Mars settlers.