I jump at the chance to see actual images – as opposed to light curves – of exoplanets. Thus recent news of a Tatooine-style planetary orbit around twin stars, and what is as far as I know the first actually imaged planet in this orbital configuration. I’m reminded not for the first time of the virtues of the Gemini Planet Imager, so deft at masking starlight to catch a few photons from a young planet. Youth is always a virtue when it comes to this kind of thing, because young planets are still hot and hence more visible in the infrared.

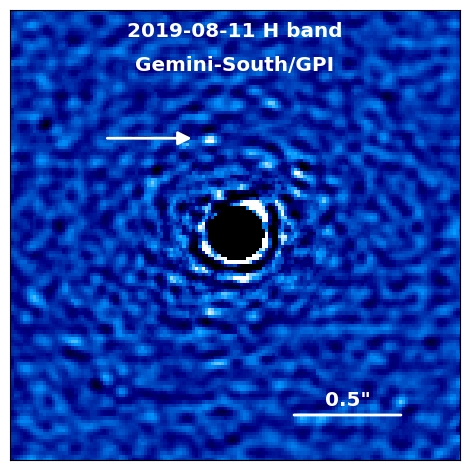

The Gemini instrument is a multitasker, using adaptive optics as well as a coronagraph to work this magic. The new image comes out of an interesting exercise, which is to revisit older GPI data (2016-2019) at a time when the instrument is being upgraded and in the process of being moved to Hawaii from Chile, for installation on the Gemini North telescope on Mauna Kea. This reconsideration picked out something that had been missed. Cross-referencing data from the Keck Observatory, what was clearly a planet now emerged.

Image: By revisiting archival data, astronomers have discovered an exoplanet bound to binary stars, hugging them six times closer than other directly imaged planets orbiting binary systems. Above, the Gemini South telescope in Chile, where the data were collected with the help of the Gemini Planet Imager. Photo credit International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/T. Matsopoulos.

European astronomers at the University of Exeter independently report their own discovery of this planet in a paper in Astronomy & Astrophysics using GPI data in conjunction with ESO’s SPHERE instrument. So this appears to be a dual discovery and the planet is now obviously confirmed. More about the Exeter work in a moment.

Jason Wang is senior author of the Northwestern University study, which appears in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. There are obvious reasons why he and his collaborators are excited about this particular catch:

“Of the 6,000 exoplanets that we know of, only a very small fraction of them orbit binaries. Of those, we only have a direct image of a handful of them, meaning we can have an image of the binary and the planet itself. Imaging both the planet and the binary is interesting because it’s the only type of planetary system where we can trace both the orbit of the binary star and the planet in the sky at the same time. We’re excited to keep watching it in the future as they move, so we can see how the three bodies move across the sky.”

So what do we know about HD143811 AB b? No other directly imaged planet in a binary system presents us with such a tight orbit around its stars. This world is fully six times closer to its primaries than any other planets in a similar orbit, which says a good deal about GPI’s capabilities. The planet itself is mammoth, six times the size of Jupiter, and evidently relatively cool compared to other directly imaged planets. Formation is thought to have taken place about 13 million years ago, so we’re dealing with a very youthful star but not an infant.

The stars are part of the Scorpius-Centaurus OB association of young stars. The HD 143811 system itself is some 446 light years away. And what a tight binary this appears to be, the twin stars taking a mere 18 Earth days to complete one orbit around their common barycenter. Their giant offspring (assuming this world formed from their circumstellar disk), orbits the twin stars in 300 years.

I suspect that the orbital period is going to get revised. As Wang says: “You have this really tight binary, where stars are dancing around each other really fast. Then there is this really slow planet, orbiting around them from far away. Exactly how it works is still uncertain. Because we have only detected a few dozen planets like this, we don’t have enough data yet to put the picture together.”

The European work, likewise consulting older GPI data, shows an orbital period with wide error margins, a “mostly face-on and low-eccentricity orbit” with a very loosely constrained period of roughly 320 years.” The COBREX (COupling data and techniques for BReakthroughs in EXoplanetary systems exploration) project specializes in re-examining data like that of the GPI, working with high-contrast imaging, spectroscopy, and radial velocity measurements. In this case, the work included a new observation from the SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch) instrument installed at ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile.

Image: HD 143811 AB b, now confirmed by two independent teams of astronomers, using direct imaging data from both the Gemini Planet Imager and the Keck Observatory. The Exeter team confirmed the discovery using ESO’s SPHERE instrument. Credit: Squicciarini et. al.

I mentioned the issue of the new planet’s formation. That’s one of the reasons this discovery is going to make waves. The overview from Exeter:

This discovery adds an important data point for comparative exoplanetology, bridging the temperature range between AF Lep b (De Rosa et al. 2023; Mesa et al. 2023; Franson et al. 2023) and cooler planets with a slightly lower mass, such as 51 Eri b (Macintosh et al. 2015). Together, these directly imaged planets of varying ages and masses offer a unique testbed for models of giant planet cooling and evolution. Moreover, HD 143811 b joins the small sample of circumbinary planets detected in imaging. Monitoring the binary with radial velocities and interferometry, along with astrometric orbit follow-up, will constrain the dynamical history of the system. While a characterization of the atmosphere is currently limited by the spectral coverage, broader wavelength and high-resolution observations especially in the mid-infrared will be essential for probing temperature structure and composition. This characterization will clarify the differences between circumbinary and single-star planets and their relation to free-floating objects.

The discovery was announced in two papers. The Northwestern offering is Jones et al. “HD 143811 AB b: A directly imaged planet orbiting a spectroscopic binary in Sco-Cen,” (11 December 2025). Now available as a preprint, with publication in process at The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The University of Exeter discovery paper is Squicciarini et al., “GPI+SPHERE detection of a 6.1 MJup circumbinary planet around HD 143811,” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 702 (2025), L10 (full text).