Among all the planets, Uranus seems to get the least play in science fiction, though it does have one early advocate whose work I’ve always been curious about. Although he wrote under a pseudonym, the author calling himself ‘Mr. Vivenair’ published a book about a journey to Uranus back in the late 18th Century. A Journey Lately Performed Through the Air in an Aerostatic Globe, Commonly Called an Air Balloon, From This Terraquaeous Globe to the Newly Discovered Planet, Georgium Sidus (1784) seems to be reminiscent of some of Verne’s work, even if it pre-dates it, in using a then cutting-edge technology (balloons) to envision a manned trip through space.

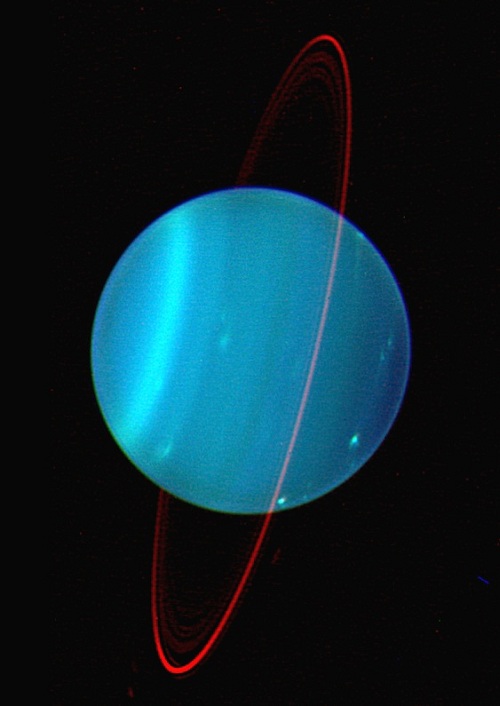

Image: Near-infrared views of Uranus reveal its otherwise faint ring system, highlighting the extent to which it is tilted. Credit: Lawrence Sromovsky, (Univ. Wisconsin-Madison), Keck Observatory.

When ‘Vivenair’ wrote, Uranus had just been discovered (by William Herschel in 1781). The author used it as the occasion for political satire, and not a very good one, according to critic James T. Presley, who described it in an 1873 article in Notes & Queries as ‘a dull and stupid satire on the court and government of George III.’ Vivenair evidently put the public to sleep, for Uranus more or less fades from fictional view for the whole of the 19th Century. More recent times have done better. Tales like Geoff Landis’ wonderful “Into the Blue Abyss” (2001) bring Uranus into startling focus, and Larry Niven does outrageous things with it in A World Out of Time (1976). But although it doesn’t hold up well as fiction, Stanley G. Weinbaum’s story about Uranus may sport the most memorable title of all: “The Planet of Doubt” (1935).

What better name for this place? The seventh planet has a spin axis inclined by a whopping 98 degrees in reference to its orbital plane — compare that to the Earth’s 23 degrees, or Neptune’s 29. This is a planet that is spinning on its side. Conventional wisdom has it that a massive collision is the culprit, but the problem with that thinking is that such a ‘knockout blow’ would have left the moons of Uranus orbiting at their original angles. What we see, however, is that the Uranian moons all occupy the same 98 degree orbital tilt demonstrated by their parent.

New work unveiled at the EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting in Nantes, France is now giving us some answers to this riddle. A team led by Alessandro Morbidelli (Observatoire de la Cote d’Azur) ran a variety of impact simulations to test the various scenarios that could account for Uranus’ tilt. It turns out that a blow to Uranus experienced when it was still surrounded by a protoplanetary disk would have reformed the entire disk around the new and highly tilted equatorial plane. The result would be a planetary system with moons in more or less the position we see today, as described in this news release.

But this is intriguing: Morbidelli’s simulations also produce moons whose motion is retrograde. The only way to get around this, says the researcher, is to model the Uranian event not as a single impact but as at least two smaller collisions, which would increase the probability of leaving the moons in their observed orbits. Given all this, some of our planet formation theories may need revision. Says Morbidelli:

“The standard planet formation theory assumes that Uranus, Neptune and the cores of Jupiter and Saturn formed by accreting only small objects in the protoplanetary disk. They should have suffered no giant collisions. The fact that Uranus was hit at least twice suggests that significant impacts were typical in the formation of giant planets. So, the standard theory has to be revised.”

The questions thus raised by the ‘planet of doubt’ may prove helpful in understanding how giant planets evolve. More on this when the paper becomes available.

Can someone explain why the explanation has to be an impact and cannot just be “wobble” due to [transient] non uniform composition? Is it a matter of the size of the forces, or the time needed to deliver the change, or some completely different factor?

Alex

I do not know… conservation of angular moment perhaps? The angle of the proto planetary disk would have defined the angle of the spin ( axis perpendicular to the disk) and assuming the disk was in a near circular orbit, the speed of the spin should have to do with the mass of the accumulated body, and the distance from the center of gravity of the disk ( where the sun was forming), and the total mass and distribution of matter in the protodisk. looking at the rest of the planets, things look pretty regular.

I’m curious if anyone has ever run the math on the results of an extrasolar body passing through the protoplanetary disk. It seems intuitive that a brown dwarf or “rogue planet” passing through could have tugged Uranus’ axis into its inclination if approaching from galactic north to south through the disk. It would also seem that this would result in reduced mass for moon formations as the body would attract material out of the solar system with it, which seems to be the case according to the wikipedia article: “The Uranian satellite system is the least massive among those of the gas giants.” [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moons_of_Uranus#Characteristics_and_groups]

Any thoughts on other possible effects of this scenario?

@jkittle

Except that it was noted that the impact with Uranus also shifted the satellite orbits with its axial change, which conventionally shouldn’t happen with simple models of dynamics and conservation of momentum.

Alex – so true.

Perhaps the moons are debris from the collision. it there were two collisions one might see two distinct populations of satellites.

We need to observe more solar systems to figure out how this all works.

I am waiting so see if they can identify any moons of some of these extra- solar gas giants that seem so ubiquitous among the stars.

For Saturn and Jupiter the interiors are hot enough they is probably no solid surface, below the think hydrogen helium atmospheres. Is it possible Uranus has a LIQUID and /or solid surface as one goes deeper? What about Neptune? given the lower gravity and temperature why are we not considering the possibility of ( microbial) life in the complex oceans of these “ice giants?”

Astrophoto: The Distant Worlds of Uranus and Neptune by Rolf Wahl Olsen

by Dianne Castaneda on October 9, 2011

Rolf Wahl Olsen captured this photo of the Uranus and Neptune system on October 3, 2011. Uranus and Neptune are currently the two farthest planets from the Sun after Pluto was demoted to a dwarf planet.

“The image was taken with my 10? f/5 Serrurier truss Newtonian and is a composite of short exposures for the planet discs and longer exposures for the fainter moons. Miranda, the smallest of Uranus’ five larger moons, was very close to Uranus when the image was taken and therefore lost in the glare of the planet itself in the long exposure image used to capture the moons. The orbits of the moons were added to illustrate the scale and orientation of the two systems as viewed from Earth, with South being towards the top of the image.

Both Uranus and Neptune are so far away from us that their angular diameters are only a few arcseconds, being 3.7? and 2.3? respectively. This makes it extremely difficult to discern any details on then and they nearly always appear as tiny cyan/blue balls except when imaged by large observatories or the Hubble Space Telescope. In fact, the entire orbit of Triton would easily fit behind the disc of Mars when the latter is at opposition. Still, with relatively modest equipment it is possible to get a good glimpse of these fascinating icy worlds.”

http://www.universetoday.com/89445/astrophoto-the-distant-worlds-of-uranus-and-neptune-by-rolf-wahl-olsen/

Liquid methane at extreme temperature and pressure: Implications for models of Uranus and Neptune

Authors: Dorothee Richters, Thomas D. Kühne

(Submitted on 20 Jun 2012)

Abstract: We present large scale electronic structure based molecular dynamics simulations of liquid methane at planetary conditions. In particular, we address the controversy of whether or not the interior of Uranus and Neptune consists of diamond.

In our simulations we find no evidence for the formation of diamond, but rather sp2-bonded polymeric carbon. Furthermore, we predict that at high tem- perature hydrogen may exist in its monoatomic and metallic state. The implications of our finding for the planetary models of Uranus and Neptune are in detail discussed.

Comments: 4 pages, 3 figures

Subjects: Chemical Physics (physics.chem-ph); Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP); Statistical Mechanics (cond-mat.stat-mech); Computational Physics (physics.comp-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:1206.4500v1 [physics.chem-ph]

Submission history

From: Thomas Kühne [view email]

[v1] Wed, 20 Jun 2012 14:00:54 GMT (38kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/1206.4500

Following up the dark spot on Uranus

Posted By Heidi Hammel

2012/09/04 06:38 CDT

Topics: pretty pictures, Uranus, optical telescopes

It was a surprise and delight to have our Icarus paper highlighted in Emily Lakdawalla’s blog. Thanks for highlighting Uranus, since it has gotten, ahem, a bum rap over the years. (You have no idea how hard we tried to come up with a paper title that did NOT say “dark spots on Uranus.”) A couple of grace notes.

It was Larry Sromovsky’s surprising discovery at the Gemini Observatory of the extraordinarily bright feature in October 2011, followed by valiant efforts of the world’s top amateur astronomers to image that feature, that allowed me to trigger the Hubble observations.

Had the feature persisted in — or increased beyond — its October brightness level, there’s a chance that more amateurs might have seen the feature. Unfortunately, it faded.

The Keck images on 10 November, while good, were not excellent due to a mis-aligned lenslet array in the adaptive optics system. In fact, we at first thought the two features were really just a horrible image of a single feature. The (still poor) images on 11 November continued to show two features, however, and it was clear they had moved relative to one another. The lenslet array was corrected and the images were exquisite but … on 12 November the feature was on the other side of the planet, and our time over.

We pleaded with the next observer, Bill Merline, to please please get us a picture of Uranus on 13 November, which he graciously did, and that allowed us to definitively identify and track the features.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/20120904-hammel-uranus-dark-spot.html

Uranus has Bizarre Weather

by Nancy Atkinson on October 18, 2012

Here’s the scene: a thick, tempestuous atmosphere with winds blowing at a clip of 900 km/h (560 mph); massive storms that would engulf continents here on Earth, and temperatures in the -220 C (-360 degree F) range.

Sounds like a cold Hell, but this is the picture emerging of the planet Uranus, revealed in new high-resolution infrared images from the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, exposing in incredible detail the bizarre weather of a planet that was once thought to be rather placid.

“My first reaction to these images was ‘wow’ and then my second reaction was ‘WOW,’” said Heidi Hammel, a co-investigator on the new observations. “These images reveal an astonishing amount of complexity in Uranus’ atmosphere. We knew the planet was active, but until now much of the activity was masked by noise in our data.”

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/98049/uranus-has-bizarre-weather/

To further quote:

The driver of these features must be solar energy because there is no other detectable internal energy source.

“But the Sun is 900 times weaker there than on Earth because it is 30 times further from the Sun, so you don’t have the same intensity of solar energy driving the system,” said Sromovsky. “Thus the atmosphere of Uranus must operate as a very efficient machine with very little dissipation. Yet the weather variations we see seem to defy that requirement.”

One possible explanation, is that methane is pushed north by an atmospheric conveyor belt toward the pole where it wells up to form the convective features visible in the new images. The phenomena may be seasonal, the team said, but they are still working on trying to put together a clear seasonal trend in the winds of Uranus.

“Uranus is changing,” he said, “and there is certainly something different going on in the two polar regions.”