Kelvin Long and Richard Osborne have seen to it that the British Interplanetary Society’s conference on the highly influential science fiction writer and philosopher Olaf Stapledon has gone off without a hitch. Here is their report from the event, a conference evidently as rife with speculation and far-future musings as anything the author himself ever penned.

by K.F. Long & R. Osborne, Symposium Chairmen

During the summer the British Interplanetary Society (BIS) played host to a symposium on World Ships, possibly the first such dedicated conference ever on these grand, long-term planning concepts. However, the most recent BIS symposium is on a topic that covers eons. There was no one who thought bigger and over longer timescales than the philosopher and writer Olaf Stapledon. Once again, the BIS has organized another first in history. On the 23rd of November members and visitors gathered to discuss the philosophy and literature of Stapledon in the context of today’s current space exploration activities. The session was organized for the purpose of facilitating wider exposure to his ideas and as a way to invite those who may never have heard of him to discover a gem in the literature of space exploration and science fiction.

William Olaf Stapledon was born in Seacombe, Wallasey, on the Wirral Peninsula near Liverpool, England, on the 10th of May 1886. He died on the 6th of September 1950. He spent much of his childhood growing up in Egypt. He obtained a BA Modern History, 1909, from Balliol College, Oxford and a PhD Philosophy University of Liverpool, 1925. His thesis was “A Modern Theory of Ethics”, later the subject of a book. He had worked as a teacher at the Manchester Grammar School and served with the Friends’ Ambulance Unit in France and Belgium during World War I. He was married to Agnes Zena Miller and together they had two children — their daughter Mary Sydney Stapledon and a son, John David Stapledon, whose nephew Jason Shenai attended the BIS symposium, much to the delight of all those present. Imagine having an actual Stapledon in the room. Many of the attendees felt elevated to a higher state of humanity this day. During the lunch Jason was presented with a small gift from the Society by Stephen Baxter, a well known science fiction author who has followed in the tradition of Stapledon and Clarke. Jason said he was really enjoying the day and found the experience moving. He said his entire family were appreciative for the event and the respect shown to his distant relative.

The BIS and Stapledon already have a long history together. On the 9th of October 1948 Stapledon gave a wonderful lecture to members of the society at the invitation of Arthur C.Clarke. It took place at St.Martin’s School, 107 Charing Cross Road, London. The BIS advert read: “In his opening lecture Dr.Stapledon will discuss the profound ethical, philosophical and religious questions which will undoubtedly arise from interplanetary exploration, the possibility of finding intelligent life on other worlds, colonization of planets, interstellar communication, and the possibility of telepathic communication”. Stapledon wrote many books in his life, including Odd John, Sirius, Worlds of Wonder, Darkness and Light. But it is for Last and First Men (1930) and Star Maker (1937) that he is most famous. From these incredible books sprang a range of ideas such as planetary terraforming, genetic engineering, human evolution, transcendence, Dyson Spheres, interplanetary genocide, and the cosmic mind, to name just a few. Arguably the daring works of Stapledon are as important an influence on our culture as the works of William Shakespeare, and yet Stapledon is not very well known throughout the world.

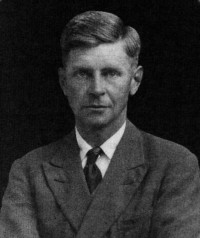

Image (top): Olaf Stapledon. The second image is of Jason Shenai, a Stapledon relative, accepting a gift from the British Interplanetary Society as presented by Stephen Baxter. Credit: Kelvin Long.

Consciousness and Convergence

To discuss his work some Stapledon thinkers came together on this special day. Kelvin Long (co-Chairman) discussed the concept of “universal mentality” and asked if it was at least credible. He pointed to possible physical limitations in the human brain due to the way neurons and axons were ‘wired’ and said this had been foreseen in Stapledon’s literature. Long argued that to become more intelligent we would converge further with technology, Homo Sapiens becoming Homo Electronicus, as Clarke had called it. Long said this would bring about a coupling to the extent that minds could join and the idea of a group mentality or cosmic union would become feasible. He discussed our own self-awareness that we are conscious and indeed aware of each other. He referred to work by the physicist Freeman Dyson who had argued in his book Disturbing the Universe that mind does appear to play a role in reality. This includes the observer dependence in the quantum description of reality and the potential for all our observations being represented by the analogue of a quantum wave function. He discussed the Hawking-Hartle wave function of the Universe. Long also talked about the various cosmic co-incidences in the universe, such as the many physical constants just being right for life, or even intelligent life to form, so-called anthropic reasoning. He ended with a discussion on the laws of physics and in particular the special theory of relativity, which demands the constancy of the speed of light. He said this would place fundamental limitations on any universal mentality or indeed the Star Maker, on how ‘it’ communicates with those that inhabit the universe. He said this law would have to be broken in order for the ‘Supreme Moment of the Cosmos’ (a term from Star Maker) to ever be feasible for all of the inhabitants of the universe simultaneously.

Andy Sawyer had visited from the Science & Science Fiction Library Special Collections and Archive of the University of Liverpool. He spoke about “The Future and Stapledon’s Visions” and quoted from Last and First Men directly: “The romance of the far future, then, is the attempt to see the human race in its cosmic setting, and to mould our hearts to entertain new values”. He talked about many of the books and ideas that had influenced Stapledon’s work in some way, such as The March of Intellect (1829) which depicted fantastic modes of transport such as balloons and steam transport. He referred to George Griffith’s images from The Angel of the Revolution (1893) and Olga Romanoff (1894). Charles Green had even set a major long distance record in a balloon by flying a distance of 480 miles, a record not broken until 1907. These sorts of developments would have found their way into Stapledon’s perspective on the world. Sawyer said that Stapledon showed that the idea of flight was linked to that of change. The culture of the First Men’s 24th-century World-State is based, technologically and spiritually, on aircraft. Sawyer impressed the audience by putting up a time chart that Stapledon had constructed for Last and First Men, complete with colored lines. Later, Andy would talk about the good work being done by the University of Liverpool Science Fiction Foundation, founded in 1971 and supporting 30,000 books and magazines in the fields of science fiction and related genres. The collection includes the Olaf Stapledon Archive and the Eric Frank Russell and John Wyndham Archives.

Patrick Parrinder, a former Professor of English at the School of English & American Literature, University of Reading, discussed “The Earth is My Footstool: Wells, Stapledon, and the Idea of the Post-Human”. Parrinder referred to Stapledon’s early life in Egypt and suggested that his mythical avatar was the Sphinx. His fiction was the portal to the mysteries of cosmic existence, unraveling the Sphinx’s riddle of the transformations of the human animal, and it does this with a Sphinx-like abstraction from domestic emotions and personal relationships. He said the Eighteenth Men whose outlook dominates in Last and First Men and Last Men in London are, we are told, both human and animal in nature, like the old Egyptian deities with animal heads. He said that later H.G.Wells had also taken the Sphinx as his symbol in a substantial work of fiction, The Time Machine, which stands alone among Wells’ novels for its unremittingly bleak view of human destiny. Stapledon apparently claimed not to have read this book when he wrote Last and First Men. The talk covered so much ground and in such a scholarly way it is impossible to do it justice in this brief article and the above is merely a snapshot of what was covered.

Kelvin Long presented a paper on behalf of Greg Matloff, Emeritus Associate Professor and Adjunct Associate Professor, New York City College of Technology. This talk was one of the most fascinating presentations of the day and was on the subject of “Star Consciousness: An Alternative to Dark Matter”. Matloff had looked for an alternative to explain the dark matter problem and proposed the hypothesis that stars may be conscious, as an exercise in philosophical speculation in the spirit of Stapledon’s literature. He pointed to models of stellar radiation pressure and stellar winds which failed to account for the anomalous stellar velocities and instead proposed psychokinetic action, a principle claimed to be now demonstrated in quantum fluctuations. He also pointed towards Parenago’s discontinuity to explain how stars can adjust their galactic velocity. Cool, red stars were said to move around the galaxy faster than hot, blue stars. Molecules were also said to be rare or non-existent in the spectra of hot, blue stars. If stars were ever found to be conscious, this would present a problem for the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) in terms of how we communicate with them. The presentation ended by saying that Descartes argued in favor of a separation of consciousness from the physical world but possibly, the entire universe may be conscious.

Technology and Paradox

After lunch Richard Osborne (co-Chairman) and a member of the BIS Council, spoke about “Dyson Spheres”. These are hypothesized artificial habitats built around a star by a civilization with sufficiently advanced technology, able to capture as much as possible of the power output of the star. Osborne said the idea had originated in 1927 from J.D.Bernal but Stapledon had included a reference to the concept in his book Star Maker: “Not only was every solar system now surrounded by a gauze of light traps, which focused the escaping solar energy for intelligent use, so that the whole galaxy was dimmed, but many stars that were not suited to be suns were disintegrated, and rifled of their prodigious stores of sub-atomic energy.” The physicist Freeman Dyson, after whom the concept was named, worked on the idea in some detail in 1960, in a paper published in Science titled “Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation”. Osborne described the various other spin-off concepts that had evolved from the original idea, including Dyson Swarms, Dyson Statite Bubbles and Dyson Shells. Other astroengineering megastructure concepts were described including Matrioshka Brains, Shkadov Thrusters, Klemplerer Rosettes, Alderson Disks and of course Ringworlds, now made famous by Larry Niven’s excellent novel of the same name.

Image: Richard Osborne presenting his work on Dyson Spheres. Credit: Kelvin Long.

Stephen Baxter then took the stage for an interesting discussion on “Where was Everybody? Olaf Stapledon & The Fermi Paradox”. He opened with a quote from Stapledon’s ‘Interplanetary Man’ lecture: “If, by one means or another, man does succeed in communicating with intelligent races in remote worlds, then the right aim will be to enter into mutual understanding and appreciation with them, for mutual enrichment and the further expression of the spirit. One can imagine some sort of cosmical community of worlds”. Baxter said that Stapledon had communicated with both H.G. Wells and Arthur C. Clarke although it doesn’t appear that H.G. Wells had any influence on the work of Stapledon’s two key publications, Last and First Men and Star Maker. He described the Fermi paradox first presented by the Italian born physicist Enrico Fermi in the summer of 1950 and pointed out it is unlikely Stapledon heard of the paradox, as he sadly passed away in September of that same year. Baxter said that the Fermi Paradox had turned out to be a good organizing principle and a great plot generator for science fiction whilst also being a deepening paradox. The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence had seen the discovery of exotic biologies on Earth, habitable realms in the solar system, the discovery of many exoplanets, the invention of multiple contact strategies, and yet there had been 50 years of silence. He said that most of the Fermi Paradox solutions tended to fall into one of three categories; ETI is here; ETI exists but has not communicated; ETI does not exist. Baxter said that both Fermi and Stapledon were cosmic thinkers but the visions of Stapledon were still not found to be consistent with the paradox that Fermi had seen that one afternoon in 1950.

Finally, Ian Crawford, a Reader in Planetary Science & Astrobiology from Birkbeck College, London, gave a masterful exposition on “Stapledon’s Interplanetary Man: A ‘Commonwealth of Worlds’ & The Ultimate Purpose of Space Colonization”. Crawford described the three main futures that Stapledon had defined; speedy (self-inflicted) annihilation, creation of a world-wide tyranny (implied stagnation), and the founding of a new kind of world where every body works for the good of the common human enterprise. But he said there are other possibilities Stapledon had not considered, such as the creation of tyrannies that may not result in technological stagnation and may still be compatible with space exploration. He said space exploration can still proceed without the prior creation of social or political utopias and pointed to Project Apollo as an example of how nation state competition had still led to progress in space.

Crawford also said that Stapledon appeared to downplay the economic and scientific motivations for space exploration, yet the former is important for maximizing human well-being and the latter is a key component of human intellectual development. He spoke about the race we appear to be in now, between cosmic fulfillment and cosmic death. A situation echoed by our current dilemma, to become a spacefaring civilization or face stagnation and decay. Crawford made the important point that in thinking about space exploration we had to justify why we want another planet and what we are going to do with it, given that we already have a planet and have not treated the Earth very well. He asked whether before we consider this question, we should consider what man ought to do first with himself. Crawford ended by pointing towards the September 2011 publication of “The Global Exploration Roadmap” by the International Space Exploration Coordination Group and said that if Stapledon were here today he would have approved of this as a sign of positive progress that humanity is starting to work together as a global community in the exploration of space.

Image: Ian Crawford discussing the possibilities in Stapledon’s fictional futures. Credit: Kelvin Long.

Kelvin Long rounded up the day with two quotes that he thought Stapledon would have approved of. The first was from Carl Sagan: “The Universe is not required to be in harmony with human ambitions”. The second was from William Hartmann: “Space exploration must be carried out in a way so as to reduce, not aggravate, tensions in human society”. In a foreword to an Orion Books reissue of Star Maker, science fiction writer Brian Aldiss said of Stapledon: “He is too challenging for comfort. The scientifically minded mistrust the reverence in the work; the religious shrink from the idea of a creator who neither loves nor has need of love from his creations”. It is well known that Arthur C. Clarke was influenced by Stapledon’s Last and First Men and he said: “No other book had a greater influence on my life…[It] and its successor Star Marker are the twin summits of [Stapledon’s] literary career”. Clarke’s work had embraced hard science fiction but with an almost mystical tone to some of his stories. Long speculated that perhaps this is a good place to be for a writer, at the boundary between what we know to be true and what we can only speculate may be possible, the boundary between reality and imagination. As C.S.Lewis once said of Stapledon, he was a corking good writer. Now is the time for others to discover the literature of Olaf Stapledon, and the imagination that sprang from the dreams within his grand philosophy. It is fitting and proper to end an article on Olaf Stapledon by giving him the final word:

“Is it credible that our world should have two futures? I have seen them. Two entirely distinct futures lie before mankind, one dark, one bright; one the defeat of all man’s hopes, the betrayal of all his ideals, the other their hard-won triumph.”

Dr. William Olaf Stapledon, Darkness and the Light (1942)

A full article on the BIS symposium will be submitted to the society’s magazine Spaceflight. The papers from the symposium will appear in a special issue of the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. Stapledon’s work, especially Star Maker and Last and First Men, remains widely available.

Concious stars? Beings made of spacetime? Certainly, if they are possible, what else may be? Surely, if we were capable of manipulating spacetime in such a way as to build a computer which is in turn capable of altering spacetime on the fine scale as we wish, what power we would have…

certainly, more than I’d trust mankind with in our current state. It certainly does push the envelope in terms of exotic life… forget biochemistries based on Hydrogen and Silicon: go for ones based on Quarks and using the strong nuclear force as an energy source.

It may turn out that the universe *is* queerer than we can suppose…

I ought to read those two books…

When I started to read SF at the end of 1952 , Olaf Stapledon had been out of print a long time. I think it took about 10 years before I noticed the Dover reprint of Last and First Men. Odd John had maybe gone into the public domain because in the early 60’s there was an odd lurid cover reprint.

When one had read 10 years’ worth of science fiction from the 1940’s and 1950’s Stapledon was a hard slog. Not that could ignore his work, like Wells he made a narrative of the philosophy of BIG THINKS. He influenced as every great SF writer. Except for Odd John I was put off by his textbook style, I found myself skimming and scanning his novels.

I always got the impression that he was strongly influenced by Darwin and set a standard for the cosmic evolution of humanity. A popular exploration was ‘homo superior’, demonstrated best by Clarke in Childhood’s End (which appears abstractly in both the film and novel version of 2001: A Space Odyssey). Theodore Sturgeon used the idea in his beautiful and breath taking novel More Than Human (1952) with it’s Gestalt being. Stapledon influenced sophisticated science fiction prose to such a subtle degree that as a writer he went off SF readers radar screens.

One notes that his ideas about sentient stars was explored in the Starchild Trilogy by the remarkable Frederik Pohl and the (forever writer) Jack Williamson ( The Reefs of Space (1964), Starchild (1965) and Rogue Star (1969)).

Stapledon’s speculations about the next step in human evolution, the homo superior idea, has taken a bit of a beating in recent evolutionary biology. However speculation on the evolution of human derived technology remains a burning topic and we don’t know where that is going.

We got the prize behind Stapleton’s door number two: “creation of a world-wide tyranny (implied stagnation)” Check out the 2005 book “Escaping the Matrix” by Richard Moore (Intel, “Moore’s Law, THAT Richard Moore!)

Leading to “defeat of all man’s hopes, the betrayal of all his ideals” At least on this material plane.

In addition to Stapleton and Clarke, there have been other SF writers and scientist/mystics who believed they had actually been contacted by ETI or metaphysical entities. Drug dreams, schizophrenia, or epiphany, is a matter of opinion.

Strongly recommended, “Radio Free Albemuth” by Philip K Dick and the autobiography of John C Lilly, “The Scientist”

Error, Richard Moore is a different Silicon Valley person than Gordon Moore of Intel, I apologize for the error, I was misled

For those interested in Stapledon’s life and thought, Robert Crossley’s biography, http://www.amazon.com/Olaf-Stapledon-Speaking-Utopianism-Communitarianism/dp/0815602812/ref=ntt_at_ep_dpt_5

is unreservedly recommended. By coincidence, I bought the book (used, it is too expensive new) recently and am about a third of the way through it. Nevertheless, I can confidently state that Crossley brings real love to his subject and I urge anyone interested in Stapledon to give it a go. Stapledon lead a remarkably interesting life and despite his limitations as a writer (though I personally have no problem with his style and even Virginia Woolf told him that “Star Maker” is the kind of book she wished she could write) and political thinker, his soaring, unstoppable imagination triumphed every time. Note: If the Crossley book is a bit much, “Last Men in London” is the closest to an autobiography. All his books warrant multiple readings.

What interests me about Stapledon is that while he was in many ways the standard issue english intellectual socialist, he came to have few illusions about socialism’s impact on humanity and remained profoundly pessimistic about it’s fate. As evidence, I point to his best novel qua novel, “Sirius.” The story of a super-dog, i.e. one possessing a human’s intelligence, serves as the ideal metaphor of an entity whose soaring spirit cannot escape it’s evolutionary constraints. There are a few smiles in the novel, but not many. The tale of the deep love between its owner, Plaxey, the daughter of the biologist who created the uber-dog, and Sirius is a great tragedy. It’s strong stuff even now; one wonders what people in the ’40s made of it. For those who worry about people getting giddy over Triumphalism, “Sirius” and “Odd John” are the cure. And if they aren’t enough, “Last Men in London” is about as downbeat as it gets.

I met a Stapledon grandson in London at a Templeton Foundation 2 day conference about Stapledonian ideas, about a decade ago. Dyson was there and felt Stapledon’s pessimism came from his experience in WWII and the obvious failures of the Soviet he once loved. I rather agree.

But as Al Jackson says the constraints of Darwinian evolution need not be ours. We have tech to help us, not just machine-man connections but better, our ability to control genetics. (One reason I started several genetics companies.)

Stapledon’s disillusion need not be ours, either. His work will live longer than I suspect he ever dreamed.

Is Greg Matloff’s paper, “Star Consciousness: An Alternative to Dark Matter”, available online? I am not sure whether to worry about him or admire his audacity. Maybe I should do both.

Hi All

LJK, the paper isn’t available, though one can always ask Greg for a copy. He makes an interesting argument, but it was more a lyrical possibility than a serious hypothesis – though testable like any good hypothesis.

Hi ljk, all the papers from the Stapledon symposium will be submitted to the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. Once published, you will just have to buy this unique issue, ;-)

I agree Greg shows great audacity here but this is the best of the scientific spirit in my view, free to speculate about what may be possible without restraint or fear of ridicule, but then of course we must always come back down to what science tells us.

Kelvin

ljk: “Is Greg Matloff’s paper, “Star Consciousness: An Alternative to Dark Matter”, available online?”

I’m interested too, but I’m rather skeptical regarding such a concept. That conscious beings do not only move according to — how should I say it? — “plain” physical laws is rather trivial and not at all an original idea.

There is really a problem. Example: If you hit me over my head and throw me from the roof of a tall building, my body will fall like any inanimate body; but, by just applying the laws of physics, no physicist is able to explain — choose your favorite: theoretically, today, … — the movements of my body while I’m writing this comment here.

But back to Matloff’s paper. I would like to know, why Matloff thinks, that conscious stars would or should move just in a way, that this does indeed correspond to the observed movement of stars in galaxies and of galaxies in galaxy clusters. Or is it a “philosophical” exercise which is completely unfounded?

On another thread from these pages I have just been disusing with kzb how the complex models that describe stellar motions in the galaxy might obscure simpler truths. My conclusion was that the simplest and most obvious of these should hail from the fact that thermodynamics dictates that if a group of stars were confined to within a common space, the distribution of the discrepancy of their velocities from their common local average will eventually be exactly inversely proportional to the root of their individual masses. Of course stars are not really so confined, so the outcome must be that “Cool, red stars were said to move around the galaxy faster than hot, blue stars”.

Thus my exasperation continues, as it seems that this fact is construed as mysterious in the quote I gave from the above passage.

I have often wondered if galaxies themselves are living beings of a kind way beyond our current experience and scale. Or if I am just anthropomorphizing here?

I distinctly recall the day I heard Carl Sagan say that we (as in all of humanity) are a way for the Milky Way galaxy to “know itself”. I then extrapolated the idea of other intelligent species also acting as galactic “minds”, since one little “brain” in such a big “body” would hardly suffice, just like certain huge dinosaurs needed collections of special nerves at key points along their bodies to assist the relatively small brains in their skulls in dealing with their massive, long bulks.

Lee Smolin has even speculated on entire universes being living beings or at least acting like one, assuming the Multiverse theory is true. As I said, it could just be us little humans trying to explain things way beyond our current limited perspectives. Not all that far off from our ancestors explaining various natural phenomenon as the actions of gods and spirits, I suppose.

If nothing else, these ideas serve to literally expand our paradigms and our appreciation for the true nature and our place in the Cosmos. We have a long way to go in our understanding of the rest of existence and looking at things from different perspectives, even if they turn out to be wrong, are a good step towards getting to the truth. And look at how much attention this particular topic, out of all the other things discussed in the Stapledon article, has garnered!

To expand upon my galaxies as living beings idea (well, I did not originate such an idea but I do have ideas on the idea, and yes I now wish I had written a paper on this for the conference).

Two possibilities on how galaxies might be alive and aware:

Galaxies might be living beings as part of their nature and makeup. As for any real intelligence with such a massive collections of stars, it may be the same as a colony of ants: They function as a unit in such a way as to appear highly organized and intelligent, but in reality are functioning more like little various software programs working in unison for the benefit of the whole – just smart enough to get their particular tasks done, but not able to truly comprehend what they are doing or why.

Small tangent: I have often wondered if this is one reason that certain advanced ETI have not bothered to contact us, as they may view us as we do the ants. Sure, we both have organized societies with hierarchies and large purposely-constructed dwelling structures, plus we both engage in similar activities such as farming, warfare, and raising our young.

However, as I said above, ants do these tasks as part of a basic evolutionary program going back millions of years, functioning like one giant organism. I can see highly advanced ETI viewing human civilization in a similar light; let’s face it, we may have some fancy, shiny toys and relatively tall buildings, but just a few centuries ago we were hardly more than an agricultural pre-industrial society and our biological traits are far more in line with chimpanzees and wolves and other lower creatures than many people often care to admit (why else would sex and sports be so widely popular with supposedly evolved intelligences? And look at how our endless political wranglings to gain social dominance have not changed in millennia).

I have always been intrigued at how galaxies seem to act like animals in that the big ones tend to “consume” the smaller ones and how ones of equal size tend to “crash” into one another: Could they be fighting or reproducing? Or maybe a strange but necessary combination of the two? As I said before, I am probably just planting my limited one-planet views on cosmic objects and forces.

My other idea on how galaxies become alive and aware is they do so via the collections of smaller beings which live around and between their stars. In this scenario, the galaxy itself is not alive, but the creatures such as humanity become its mind and sense organs. Perhaps they eventually evolve and merge to turn the galaxy into the actual massive living being, functioning on scales of space and time much longer than any living thing on Earth and limited only by the speed of light (unless such a Galactic Mind can find a way to transcend it as well – or perhaps a being that lives for many billions of years does not need to rush about anything).

I recall reading a science fiction story from one of the SF magazines about twenty ago (I can remember neither the title nor author, darnit) about two fellows living in a future interstellar-spanning society speculating on galaxies being alive. I wish I could recall all the details, but I do remember at the end they speculated that all the electromagnetic buzzing by the various civilizations communicating with each other across the Milky Way galaxy might be giving our galaxy the combination of a “headache” and interfering with its ability to think and talk with other galaxies in the Universe. Noting that while most galaxies are moving away from each other, the Andromeda galaxy and ours are actually headed towards each other, one character wonders if M31 is responding to the Milky Way’s request to help deal with its “pest” problem.

If anyone knows what story I am referring to and can send me a copy, I would greatly appreciate it, thank you. And thanks for bothering with my cosmic ramblings.

Three of Stapledon books are available as free downloads at the ManyBooks site, including Star Maker.

Here’s the link: http://www.manybooks.net/authors/stapledono.html

Rob Henry,

While that’s quite true the explanation lacks poetry.

I think we have a time scale problem here. If galaxies were alive, they would have needed time to evolve. It took us a tenth of the age of the universe to do this, those galactic beings would have had at most a few thousand generations.

Rob, in a way, stars are confined by their orbits around the galactic center. The question really is if they interact enough to thermalize during the few billion years they have had. If so, we should see lighter stars leave, i.e. “evaporate”, and heavier stars concentrate (precipitate?) towards the center. Or not?

Eniac, I always thought that those who pushed the possibility of living galaxies relied on a steady state model of the universe to fix that evolution problem.

As to that unrelated problem of larger stars in the galactic centre, their lifetimes are so short that their distribution should be dominated by their region of birth. The only effect that should be noticeable is a relative depletion of M dwarfs and these would be so hard to study at the distance of the galactic core, that I imagine that dissuasion on their distribution there might be infrequent. I note that all other stars have similar masses.

Eniac: “in a way, stars are confined by their orbits around the galactic center”

As far as I know, galaxy collisions occur rather often and lead to the exchange of stars between galaxies. So, many stars are not confined to their orbits around the center of one galaxy.

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2011/12/still-lookingfor-extraterrestrial-life.html

Monday, December 5, 2011

Still looking…for extraterrestrial life

Time for definitions…

Abstract:

When we try to search for extraterrestrial life and intelligence, we have to follow some guidelines. The first step is to clarify what is to be meant by “Life” and “intelligence”, i.e. an attempt to define these words. The word “definition”refers to two different situations. First, it means an arbitrary convention. On the other hand it also often designates an attempt to clarify the content of a preexisting word for which we have some spontaneous preconceptions, whatever their grounds, and to catch an (illusory) “essence” of what is defined. It is then made use of pre-existing plain language words which carry an a priori prescientific content likely to introduce some confusion in the reader’s mind.

The complexity of the problem will be analyzed and we will show that some philosophical prejudice is unavoidable. There are two types of philosophy: “Natural Philosophy”, seeking for some essence of things, and “Critical (or analytical) Philosophy”, devoted to the analysis of the procedures by which we claim to construct a reality. An extension of Critical Philosophy, Epistemo-Analysis (i.e. the Psycho-Analysis of concepts) is presented and applied to the definition of Life and to Astrobiology.

“Philosophy and problems of the definition of Extraterrestrial Life” by Jean Schneider:

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1112/1112.0222.pdf

The New Universe and the Human Future

How a Shared Cosmology Could Transform the World

by Nancy Ellen Abrams and Joel R. Primack

http://new-universe.org/

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2012/07/commonwealth-of-worlds-and-olaf.html

Monday, July 9, 2012

A Commonwealth of Worlds and Olaf Stapledon

Abstract…

In his 1948 lecture to the British Interplanetary Society Stapledon considered the ultimate purpose of colonising other worlds. Having examined the possible motivations arising from improved scientific knowledge and access to extraterrestrial raw materials, he concludes that the ultimate benefits of space colonisation will be the increased opportunities for developing human (and post-human) diversity, intellectual and aesthetic potential and, especially, ‘spirituality’. By the latter concept he meant a striving for “sensitive and intelligent awareness of things in the universe (including persons), and of the universe as a whole.”

A key insight articulated by Stapledon in this lecture was that this should be the aspiration of all human development anyway, with or without space colonisation, but that the latter would greatly increase the scope for such developments.

Another key aspect of his vision was the development of a diverse, but connected, ‘Commonwealth of Worlds’ extending throughout the Solar System, and eventually beyond, within which human potential would be maximised.

In this paper I analyse Stapledon’s vision of space colonisation, and will conclude that his overall conclusions remain sound. However, I will also argue that he was overly utopian in believing that human social and political unity are prerequisites for space exploration (while agreeing that they are desirable objectives in their own right), and that he unnecessarily downplayed the more prosaic scientific and economic motivations which are likely to be key drivers for space exploration (if not colonisation) in the shorter term.

Finally, I draw attention to some recent developments in international space policy which, although probably not influenced by Stapledon’s work, are nevertheless congruent with his overarching philosophy as outlined in ‘Interplanetary Man?’

“Stapledon’s Interplanetary Man: A Commonwealth of Worlds and the Ultimate Purpose of Space Colonisation” by I. A. Crawford

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1207/1207.1498.pdf