Growing up in the American Midwest, I used to haunt the library in Kirkwood, Missouri looking for books on astronomy. I had it in mind to read all of them and I pretty much did, looking with fascination at fuzzy images of distant objects I yearned to see close up. What did Saturn look like from Titan? What would it be like to be close enough to see the Crab Nebula fill the sky? Breathtakingly, what would it look like to be inside one of the great globular clusters?

Early on in Vernor Vinge’s A Fire Upon the Deep the character Ravna finds herself looking out a window at the entire Milky Way from a distance sufficient to view it whole:

She’d guessed right: tonight the Galaxy owned the sky… Without enhancement, the light was faint. Twenty thousand light-years is a long, long way. At first there was just a suggestion of mist, and an occasional star. As her eyes adapted, the mist took shape, curving arcs, some places brighter, some dimmer. A minute more and … there were knots in the mist … there were streaks of utter black that separated the curving arms … complexity on complexity, twisting toward the pale hub that was the Core. Maelstrom. Whirlpool. Frozen, still, across half the sky.

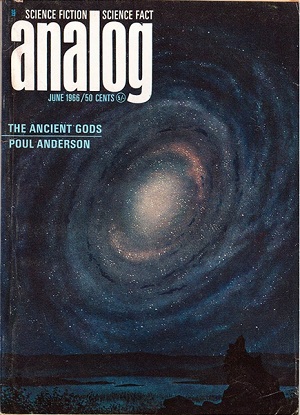

When I read that, all I could think was that I’d like to know what Chesley Bonestell would have done with the scene. The memory stuck with me, enough so that last weekend, I went digging through my collection of old magazines in search of a particular cover. We had been talking on Centauri Dreams about a Poul Anderson story called World Without Stars, and having been reminded of it by several readers, I kept thinking it was in a 1960s era Analog, and that Bonestell had indeed done a cover showing the Milky Way.

Soon I had magazines spread all over my office floor but couldn’t put my hands on the right one. The problem was that while I remembered (vaguely) the plot, about a crew that found itself tens of thousands of light years outside the galaxy on a mission to an isolated technical civilization, I had forgotten the original title. Finally I did the obvious and ran World Without Stars through the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, where I found the issue numbers. It turns out the story was serialized in Analog’s June and July, 1966 issues as The Ancient Gods, and my memory of a Chesley Bonestell cover was correct.

But serendipitous things happen when you collect old magazines. In leafing through the June issue, I came across a letter Poul Anderson had written to John Campbell, then in the latter part of his long run at the magazine — Campbell published it in Brass Tacks, his letter column, even though it was really just directed at the editor. Anderson talks about having been at Bonestell’s place and seeing the cover art for The Ancient Gods.

Did you notice in the Vinge paragraph above how dim the galaxy is depicted as being? Ravna thinks to herself that 20,000 light years is a long way out, and Anderson’s crew was to be a lot further out than that. Bonestell had been thinking all this over and had to find a way to work it into his painting. Thus Anderson to Campbell in the letter:

One point came up which may interest you. Though the galaxy would be a huge object in the sky, covering some 20? of arc, it would not be bright. In fact, I make its luminosity, as far as this planet is concerned, somewhere between 1% and 0.1% of the total sky-glow (stars, zodiacal light, and permanent aurora) on a clear moonless Earth night. Sure, there are a lot of stars there — but they’re an awfully long ways off!

If you look at the Bonestell cover, it does appear to be glowing more brightly than this, but Anderson says this is not a contradiction. His imagined planet’s natives, he points out, are adapted to the dim light of the red dwarf they orbit (no tidal lock here, evidently), and the galaxy in their night would appear luminous enough. Anderson adds: “To us, galaxies look brilliant in an astronomical photograph — but that picture involved a huge light-gathering mechanism plus hours of exposure. We could make the Milky Way look just as bright if we wanted to.”

Anyway, Bonestell had to come up with something that would be bright enough to be interesting while still suggesting the distances involved, and he certainly manages this. For the humans who have just landed on this remote world, the galaxy at 200,000 light years out is indeed a dim spectacle, as described in the story:

This evening the galaxy rose directly after sunset. In spite of its angular diameter, twenty-two degrees along the major axis, our unaided eyes saw it ghostly pale across seventy thousand parsecs. By day it would be invisible. Except for what supergiants we could see as tiny sparks within it, we had no stars at night, and little of that permanent aurora which gives the planets of more active suns a sky-glow.

And later:

Vast and beautiful, it had barely cleared the horizon, which made it seem yet more huge. I could just trace out the arms, curling from a lambent nucleus… yes, there was the coil whence man had come, though if I could see man by these photons he would still be a naked half-ape running the forests of the Earth…

Keep going further out and galaxies tend to all but disappear. Greg Laughlin noted this back in 2005 on his systemic site, where he discussed the beauty of objects like M104, the Sombrero Galaxy, which seen from a distance a bit further than Anderson’s 200,000 light years, would appear as “only a faintly ominous, faintly glowing flying saucer.” M31, the great Andromeda galaxy, is larger than the full Moon in the sky, but go out tonight and try to find it. Laughlin adds: “Our Galaxy, the Andromeda Galaxy, and the Sombrero Galaxy are all essentially just empty space. To zeroth, to first, to second approximation, a galaxy is nothing at all.”

More power, then, to long CCD time exposures and big mirrors, allowing us to see the things our eyes would perceive only dimly. Part of the thrill of those early library days was in looking at spectacular objects and trying to imagine them close up. But it was a thrill of equal measure to begin to learn about the wavelengths of light, about the gathering of photons, and the way we can tease out information about the universe with instruments designed to surmount our limitations.

Compared to the vast emptiness of galaxies, planetary systems are practically solid objects. And compared to the unimaginable void between galaxies, the galaxies themselves are practically solid objects.

Over the decades I have read so many descriptions

like that; that I want to go visit, in a real ship

not some Acme rocket.

Bonestell did a number of views of the galaxy with widely varying intensities and looks. I’ve posted some scans from “The Art of Chesley Bonestell” and “Beyond the Solar System”.

http://imgur.com/EbdbBzp

http://imgur.com/s3rKuVV

http://imgur.com/5wg0fVK

http://imgur.com/pOEuPX2

http://imgur.com/nKMPwg6

Interesting if we shot out of the plane of the Milky way at greater than say 0.999c we would see the whole of the Milky way as if we were looking down on it (distorted though). In fact as we get faster and faster towards c the whole Universe appears to emanate from the front. Weird huh?

I’m not comparing myself to Bonestell, but I made this composite image of our galaxy as seen from 10K LY above the core. The arms are wrong – I was just illustrating the central bar and low surface brightness to a group.

It may still be too bright:

http://imgur.com/4uliY8s

This is clearly written by and commented on by Northern Hemispherites. Your reference is Andromeda: App mag 3.4

Ours is the LMC at 0.9 and the SGM at 2.7, and the larger of those is very easy to find and see beyond city lights.

I am surprised at your poor descriptions, and have heard form an astronomer here that our own galactic nucleus would be bright enough to cast shadows at Magellanic cloud distances (we are shielded from it by masses of dust in the galactic plane). This sounds more realistic to me, as given the abnormally low surface brightness of the LMC, our nucleus must be spectacular – though I could well believe our spiral arms might prove a let down.

Ah – growing up in the southern hemisphere we experience this when looking for the Magellanic Clouds. These faint wisps in the sky at first tease you from the corner of your eye and you look at them thinking you’re mistaken. And then they slowly brighten, you look away and in the corner of your eye they are there. So you look again but you’re not sure they are not just puffs of cloud.

Most people never see the clouds or realise what they are.

Well, Bonestell takes the biscuit and I think I have every book that ever collected his astronomical and space flight artwork… and I know of more than a dozen other space artists …. who are excellent…

However I remember when Astronomy Magazine first started , back in 1973, for years (I don’t know how many years) it featured the work of artist Adolf Schaller on it’s cover, the reason I subscribed to the magazine, besides it being a good astronomy magazine, it’s still around, … was because of those Schaller’s.

Schaller is still about, he did work for three books, the most famous of which is Extraterrestrials: A Field Guide for Earthlings …

I did know he worked on Sagan’s Cosmos and is still around….

but there has never, as far as I know, been a book collecting his astronomical art. I would love to have one!

I don’t even know how to buy prints of his works!

http://www.omnicosm.com/

It’s a fascinating topic, what is our own galaxy actually like, and it’s far from settled in the literature. It seems to becoming settled that it is a barred spiral, and that the rotation speed is about 240km/s, significantly higher than the standard value of 220km/s. There is a large dispersion in the mass determinations by other methods though.

Another interesting thing is that active star-forming regions have been detected at over 20kpc galactic radius, and disk stars can be detected out to at least 23kpc. So, the galaxy goes on for quite a bit further than the traditional 100,000LY disk diameter.

There have been papers claiming that the Milky Way galaxy is underluminous for its mass. It is a 2-sigma outlier from the Tully-Fisher relation, and this seems to be the consensus. But there is another paper which says the luminosity has been underestimated, because our locality is between spiral arms. Hence, less luminous than average for its galactic radius.

Okay, let us see. It is often said we are similar to Andromeda. Now the SMC is close on a quarter its angular area, so for misleading comparison

(that I think is being done here), we bring it twice as close. The problem is, most of that luminosity is in the core, which can’t be more than a fifth its diameter, so we must bring it ten times closer. That would give it a magnitude of -1.6 for the same area. It should be very easy to see even for us at a quarter million light years distance with a full moon. Here we are ten times closer still, with 100 times more light. I bags that the human eye would have a spectacular view of the brightest parts of the nucleus, and a clear view of the rest of it. I further bags that those wispy bits that we must look carefully to see will prove to be only arms – though I am extremely doubtful of the gaps between them appearing very dark (what was that bit of prose suppose to mean? – that the blinding light of the distant galaxies behind was blocked by dust lanes!?)

Surface brightness (i.e light per unit area on the sky from an extended object rather than a point source) does not change with distance (neglecting red shift and other cosmological effects).

That’s not to say a large object wouldn’t be more noticeable than a small object of the same surface brightness of course.

Also, there is much less light pollution in space and your “sky” is darker than it is on Earth, so you undoubtedly could make out lower surface brightness areas better than here. But I think that’s what it would be, allowing your eyes to dark adapt to the max. I think the spiral arms would be comparable brightness to to the Milky Way as seen from Earth.

Space artist Jon Lomberg has done a number of artworks depicting the Milky Way galaxy from the outside. Here is one from the perspective of one of the Magellanic Cloud galaxies:

http://www.jonlomberg.com/original_art/oa_barred_spiral_galaxy.html

And one titled Portrait of the Milky Way:

http://www.jonlomberg.com/original_art/oa_portrait_of_milky_way.html

This one was made famous in the original Carl Sagan Cosmos series:

http://www.jonlomberg.com/limited_edition/le_approaching_milkyway.html

And on the cover of the original 1985 edition of the novel Contact, also by Sagan:

http://www.jonlomberg.com/limited_edition/le_contact.html

kzb writes

“Surface brightness (i.e light per unit area on the sky from an extended object rather than a point source) does not change with distance (neglecting red shift and other cosmological effects).”

And he is almost right.

At sufficient distance this is correct, but where angular areas are high this is wrong. Think of the Earth and sun. Now place it at one solar radius (not recommended) and it takes up exactly half the sky. Now place it at two radii and it distends an angle of 60 deg, which equates to 13.4% of a hemisphere. The problem is, that at twice the distance we intercept four times as much light, so reducing its average surface brightness by 46%. At just 20,000 light years fron the galactic core, such effects are important, but, subjectively, kzb’s statement will ‘ pass with a push’ for most purposes.

Rob Henry: hmmm not sure if you are right. In these close geometry situations with extended sources it gets very complicated. I know this from radiation detectors, where the geometry factor is usually modelled (Monte Carlo) rather than calculated.

When you say ‘at twice (think you mean half) the distance we intercept four times as much light’, this is only true for a point source (the flux per unit area at distance r is 1/4pir^2). For an extended source, the flux received per unit area versus perpendicular distance from the source centre won’t be a simple 1/r^2 ratio.

Once more interesting kzb

For the case I gave the object (the sun) is completely rotationally symmetrical, and there is only one point on Earth where it distends the entire sky. That makes it easy to prove (in this case) that the luminosity drops off with the square of distance right up to the very surface. If you can’t quite visualise it, just imagine covering a sphere around the entire sun with Earth subsolar viewing points. This area MUST be the exact inverse of the luminosity since light rays cross it just once, so cross each successive sphere counts the same number of solar photons. Calculating The angular area relation is far more complex and therein lies the problem.

I didn’t realise we were treating it as a 3D object. In the situation you described earlier, because the radius of the sun is significant compared to the Earth-Sun distance, then yes you have to take that into account as well.

Assuming for now that the source is a flat disk with neglible depth, I think what you are not taking into account is the distance to the edge of the disk is further than to its centre. It’s the hypotenuse of a triangle.

As to what it all means I will have to work that out for myself. In the meantime do you have a reference for your argument or is it something you have worked out?

Space artist Joe Tucciarone has made several pieces of the Milky Way galaxy as seen from a distance. See here:

http://www.joetucciarone.com/g_gallery.html

@kzb -I first noticed it long ago when I found it put out certain calculations I made a percent of so from seemingly equivalent alternative methods, but I have never seen anything written on it.

And yes, I have also thought of how the effect would differ from approaching a disk along its axis, but just too many extra simplifying assumptions are need, such as what is the function of unit surface luminosity with radius, and is the light transmitted evenly in all directions from each point on its surface (true for a galaxy, but what of light generated in an accretion disc beneath its surface then refracted through the outer layer.)

I think there is a lot of artistic licence in these pictures ! Whatever the arguments about the geometry factor, the fact remains that all large galaxies have a limiting maximum surface brightness (this was an empirical law until low surface brightness galaxies were discovered). And that surface brightness is so low is actually difficult to see with the naked eye.

This is definitely a fascinating topic- I’d love to see what our galaxy really looks like from outside. I imagine it would be faint, but spectacular to dark-adapted eyes… however, you don’t have to leave the Milky Way in order to see our galaxy.

If you want to see what our galaxy looks like from the inside, just go to a place with a reasonably dark sky away from city lights. At the right times of year, the Milky Way appears as a palely glowing band of light stretching across the sky with mysterious dark patches scattered across its length. Those are the dust clouds that obscure our view of the galactic center. On a dark night, it is easy to see why earlier people thought that our galaxy looked like spilt milk from a goddess’s breast.

Back on seeing the galaxy from outside, the angle you were viewing the galaxy from would matter. Viewed from above the galactic plane, you would see both the spiral arms and the nucleus- viewed straight on, the galaxy would appear like a giant, glowing sunflower. From what I know of galaxies, the nucleus tends to be the brightest part- and is actually what we see when we find the Andromeda Galaxy, so the nucleus would be the brightest part of our galaxy seen from outside. But, if we are viewing the Milky Way “sideways”, from a point outside in line with the galactic plane, it would probably look much the same as it does on a dark summer night on Earth, only smaller and fainter. You’d see a streak of light running through part of the sky.

As fantastic as these views would be, today I find it hard imagine that humans will ever explore outside of our galaxy. The distances stagger the imagination. By comparison Alpha C is just a short hop. It is possible in principle to imagine such voyages, but harder to see how to achieve them without resorting to the sort of millennial mega-engineering that went into Robert Page Burruss’s galaxy-ship… or waiting for the development of hyper-space warp drive, perhaps forever. Also, the Milky Way contains hundreds of billions of stars and undoubtedly countless planets as well, of which a small fraction could be habitable. More than enough to keep us occupied for a long time to come. Galaxy Survey will have a large job on its hands, that is for sure.

The funny thing is, though, that when one factors in the relative distance between galaxies compared to their size, they don’t seem quite so far apart, relative to their own size, than do stars and solar systems in galaxies. For instance, the Andromeda Galaxy is 1.5 million Ly away- approximately 25 Milky Way galaxy- lengths, as the Milky Way is 100,000- 120,000 Ly across. But, if our solar system were reduced to a 5 cm. model, the nearest stars would still be two-and-a-half football fields away. If one had truly galaxy-spanning stardrives able to take you around the galaxy in, say, a week, hops to other galaxies would become relatively easy. But, you would still have the problem of finding time to survey all those stars- and filing cabinets large enough to keep all those survey reports in!!

“The funny thing is, though, that when one factors in the relative distance between galaxies compared to their size, they don’t seem quite so far apart, relative to their own size, than do stars and solar systems in galaxies.”

Unfair comparison Christopher Phoenix, you are comparing systems of bodies with bodies. The Sun might be 12,000 earth diameters away, but it is 390 Earth-moon diameters. Likewise, Jupiter is 5,500 diameters away, but the real comparison is to take its Galilean system giving 200. So Sol is roughly ten x as ‘spaced out’ by my reckoning.

Christopher Phoenix:

A Terabyte drive that you can get for less than $100 will easily hold the coordinates of all the stars in the galaxy. Modern sky surveys are more expensive, but in principle able to produce this data in a very short time, (kilo- or mega-stars per second, I suppose). I think the main problem is that most of the stars are obscured or too far away to make out, not the data acquisition rate.

Coordinates is not all, of course, and you are talking of actually going there and looking at things. This will happen in time as humanity expands, exponentially. After a surprisingly short time (given FTL travel) there could be an outpost for every star, and finding filing cabinet space would suddenly not be as much of an issue. Given a galactic internet (also FTL), you could have instantaneous access to all hundreds of billions of survey reports, as if they all were in one gigantic cabinet.

Mind-boggling, really.

Putting the data problem more simply: We have 6 billion people on Earth. We are managing detailed data on those quite well (using real old-fashioned filing cabinets in most cases, too), and another two orders of magnitude does not seem all that daunting.

Rob Henry: consider this !

(1) If you are one solar radius away from the sun’s surface, you cannot see its full diameter. If you were above the pole, you could not see a sunspot on the equator. This is akin to the distance of the horizon when at a certain distance above ground.

(2) I don’t think the luminosity drops off with the square of distance right down to the surface. I’ve had an epiphany about this. Just like with gravity, I suspect a luminous sphere can be modelled as a point source as you say. But the key point for photon flux is, the distance is measured in multiples of distance to its CENTRE, not its surface.

Let’s say a star is 500,000 km in radius, and the observer is one radius away from its surface. He or she is 1 million km from its centre. If he or she then moves to 2 million km from the star’s centre, the photon flux follows 1/r^2 and is one-quarter. But the key thing is, distance from the star’s surface is not doubled, it has gone from 0.5 to 1.5 million km (i.e tripled). How’s that?