Our theories of planet formation grow more mature as the exoplanet census continues, but I’ve always speculated about the first planets discovered and how they could have possibly been where we found them. The discovery of the planets around the pulsar PSR B1257+12 occurred in 1992, the work of the Polish astronomer Aleksander Wolszczan. Anomalies in its pulsation period — this is a millisecond pulsar with a period of 6.22 milliseconds — led Wolszczan and Dale Frail to produce a paper on the first extrasolar planets ever found.

We wouldn’t find such planets at all if it were not for the effect of their gravitational pull on the otherwise regular pulses from the pulsar. But how could the planets now know as Draugr, Poltergeist and Phobetor, the latter found in 1994, possibly have formed in such an environment? After all, a dense neutron star (a pulsar is a highly magnetized, rotating neutron star) is the result of a supernova that should have destroyed any planets nearby, making it necessary for planet formation to occur from raw materials around the resulting object.

Jane Greaves (University of Cardiff), working with Wayne Holland (UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Edinburgh) presented results at the recent National Astronomy Meeting that the duo have assembled into a new paper. The researchers focused on the Geminga pulsar, about 800 light years from the Sun in the constellation Gemini. A quick check of Wikipedia produced this delightful bit about the name Geminga: It’s a contraction of ‘Gemini gamma-ray source’ as well as a transcription of words meaning ‘it’s not there’ in the Lombard dialect of northern Italy.

Geminga really is there, and at one point the explosion that created it was considered the reason for the low density of the interstellar medium through which the Sun now passes, a theory that is now out of favor. Greaves and Holland observed Geminga at submillimeter wavelengths with the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii. The pulsar is surrounded by a pulsar wind nebula (PWN), a type of nebula found inside the shells of supernova remnants that is powered by pulsar ‘winds’ driven by the central pulsar.

Indeed, earlier data from the WISE mission had suggested a ‘shell-like parabolic structure comprising a number of clumps’ around Geminga, and the authors’ new work amplifies on that discovery. Multiple observing runs with different cameras showed Greaves and Holland faint material near the pulsar and an arc around it. Says Greaves:

“This seems to be like a bow-wave – Geminga is moving incredibly fast through our Galaxy, much faster than the speed of sound in interstellar gas. We think material gets caught up in the bow-wave, and then some solid particles drift in towards the pulsar.”

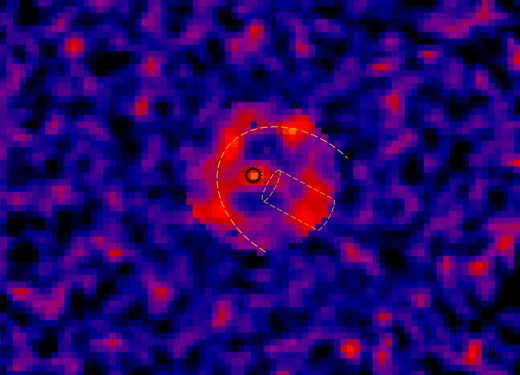

Image: Data at wavelength of 0.45 mm, combined from SCUBA and SCUBA-2 [the cameras used in this work] in a false-colour image. The Geminga pulsar (inside the black circle) is moving towards the upper left, and the orange dashed arc and cylinder show the ‘bow-wave’ and a ‘wake’. The region shown is 1.3 light-years across; the bow-wave probably stretches further behind Geminga, but SCUBA imaged only the 0.4 light-years in the centre. Credit: Jane Greaves / JCMT / EAO.

The hypothesis, then, is that dust from the interstellar medium interacting with the pulsar wind nebula around Geminga accumulates the raw materials for future planets, rather than interactions between the pulsar wind nebula and the pulsar itself. The pulsar’s movement through the interstellar medium is the key, at least for this pulsar. From the paper:

The origins of the rare pulsar planet systems are uncertain, with recent work (Margalit & Metzger 2017) favouring disruption of a companion over re-accretion of supernova fallback material. Here we find evidence that the middle-aged Geminga pulsar is surrounded by a shell of material which could have formed from compression of the local ISM. Preliminary calculations suggest that dust could penetrate the nebula, given the low space speed and local density, and this may provide an alternate source for dust near this pulsar. A candidate circum-pulsar disc would be the first to be found in the submillimetre, complementing the only infrared candidate (around the magnetar 4U 0142+61, Wang et al. 2006).

And the researchers seem to have found enough mass to do the job:

We are waiting for higher-resolution follow-up data, but can infer that any dust disc present around Geminga should exceed about 6 Earth-masses of dust. Thus it would have potential to form low-mass planets, such as the archetypes around PSR B1257+12 (Wolszczan & Frail 1992).

The authors have applied for time on the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), hoping to tease out more detail, enough to demonstrate that the faint debris they have spotted so far around Geminga really is associated with the object. A confirmation there would lead to work on other pulsar systems to probe deeper into planet formation in unusual environments.

The paper is Greaves & Holland, “The Geminga pulsar wind nebula in the mid-infrared and submillimetre,” published online by Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 15 June 2017 (abstract).

When I was a student in Astronomy, me and my Professor had a laugh at the proposal to look for pulsar planets that way. We thought it was like the joke of the drunk looking for his keys under a lamppost.

Have other pulsar planets been found?

Did you buy them a drink? ;)

The BIG question here is: Could ANY of that “dust” be composed of EITHER ice OR hydrated minerals so that a source of water could be available to any emerging planets, or would such planets be the ABSOLUTELY driest planets in the universe? I only ask this because it has been postulated that Draugr and Poltergeist could have had life develop on them DEEP UNDERGROUND, and evolve in a way that by-products of chemical reactions produced by extremely high radiation at the surface, and then transported underground via plate tectonics! A recent paper has even been bold enough to state that ATMOSPHERES are SUSTAINABLE on such planets if the pulsar ITSELF were the result of a white dwarf MERGER! Life on the SURFACES of pulsar planets would be an ABSOLUTE mind-blower!!!

SORRY: Include the following in the above comment: …tectonics, would be the energy source they use! A…

Habitable planets around pulsars theoretically possible

dinsdag 19 december 2017, 08:36

It is theoretically possible that habitable planets exist around pulsars. Such planets must have an enormous atmosphere that convert the deadly X-rays and high energy particles of the pulsar into heat.

That is stated in a scientific paper by astronomers Alessandro Patruno and Mihkel Kama, working in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. The paper appears today in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

http://www.astronomie.nl/#!/index/_detail/gli/habitable-pulsar-planets-theoretically-possible/

It is the first time that astronomers try to calculate so-called habitable zones near neutron stars. The calculations show that the habitable zone around a neutron star can be as large as the distance from our Earth to our Sun. An important premise is that the planet must be a super-Earth with a mass between one and ten times of our Earth. A smaller planet will lose its atmosphere within a few thousand years. Furthermore, the atmosphere must be a million times as thick as that of the Earth. The conditions on the pulsar planet surface might resemble those of the deep sea at Earth.