Most of us fortunate enough to see 2001: A Space Odyssey in a theater when it was released never dreamed it would spawn a strange ‘twin.’ But as Larry Klaes explains in the essay that follows, Dark Star was to emerge as a telling satire on the themes of the Kubrick film. Originating in the ideas of USC film students John Carpenter and Dan O’Bannon, Dark Star likewise plays into the screenplay for 1979’s Alien in ways that have to be seen to be believed. Larry is quite a fan of the film, and explains how and why socially relevant screenplays like these would soon be swamped by blockbuster hits crammed with special effects (think Star Wars). But that orange ‘beach ball’ still has a place in film history. Read on.

By Larry Klaes

Science fiction has certainly played an important role in inspiring and influencing humanity’s future directions. The father of American rocketry, Robert H. Goddard, was moved to imagine sending a vessel to the planet Mars as a young man in 1899 after reading The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells published just a few years earlier. From that spark developed a life-long dedicated pursuit of space exploration by Goddard, whose work in turn influenced others which eventually led to real rockets carrying real spaceships to the Red Planet and far beyond.

Conversely, science fiction also reflects the era it is created in. This can be seen in the changing depictions of the future during the Twentieth Century. While there are always exceptions, up into the 1960s the future was most often shown as a wonderful utopia, extrapolating from the real scientific and technological progress made in the preceding decades and centuries. Destination Moon (1950) had a contemporary near-future with a nuclear-powered rocket taking the first men to Earth’s natural satellite. Six years later, Forbidden Planet assumed the 23rd Century will have humanity working together to explore and colonize other worlds across the galaxy in faster-than-light (FTL) starships.

On television, Walt Disney presented an amazing future in full animated color with series such as Man in Space (1955-1959) and Magic Highway, USA (1958). The Jetsons (1962-1963) gently spoofed many future tropes such as flying cars, robot maids, pushbutton conveniences, and vacations on the Moon while simultaneously reinforcing the preconceived notions of its contemporary audiences that its depictions of society in the year 2062 were going to become an overall accurate one by then.

The belief in a “shiny, happy” future, thanks to science and technology, was also heavily supported by World’s Fairs, especially the ones held in New York City in 1939 and 1964-1965 and Seattle in 1962. There visitors not only got to see the “wonders of tomorrow” but also interact with them, cementing their realities. That each fair had a time capsule meant for some distant epoch (the New York ones are to be opened together in the year 6939, five thousand years hence, which is roughly how long human civilization had already existed) showed their makers’ faith that not only would our species still exist in the far future, but they would also be capable of finding, opening, and appreciating these preserved gifts from their undoubtedly less sophisticated ancestors.

Even when 2001: A Space Odyssey came along in 1968 in the midst of major social and cultural changes throughout the United States and abroad – and 1968 was a particularly dramatic year in that regard – the film still contained many trappings of the technological utopia, in no small part due to co-screen writer Arthur C. Clarke and the numerous real space experts they consulted in the making of 2001.

Clarke was one of the leading authors from science fiction’s “golden” era, which most often depicted space travel as a wondrous marvel in itself. Not only was voyaging into outer space considered something noble, it was also a major objective humanity was expected to strive for in its relentless pursuit of progress and new frontiers to conquer. Space had become especially important since most of Earth’s surface had already been considered “conquered” by our civilization, with the exception of the planet’s vast oceans of water: They were still largely unknown, particularly the sea bottom, which lay in total darkness under miles of crushing pressure from all that salt water.

Produced and released on the advent of the first manned lunar expeditions, 2001 predicted that the next three decades of the Space Age would have sleek space planes making regular trips to huge wheeled space stations in Earth orbit (with Hilton Hotels and Howard Johnson’s restaurants), sophisticated bases on the Moon, and nuclear-powered spacecraft operated by a “thinking” artificial intelligence (AI) carrying astronauts all the way to the gas giant planet Jupiter (or Saturn in the film novelization by Clarke).

However, if one looked more closely at this rosy and exciting depiction of our space future, there were some definite shadows among all that sunshine. The first “astronauts” we meet in 2001 are not the macho test pilots contemporary audiences were well accustomed to by the end of the first decade of the Space Age, but more often than not were bureaucrats and businessmen. For them, a journey to the Moon to inspect a mysterious alien artifact found there was treated more like a standard terrestrial corporate trip than an exciting scientific adventure.

As for that mission to Jupiter, its real objective was to examine an even larger alien artifact orbiting that distant world, which the one dug up on the lunar surface had sent a signal to. The original planetary science mission of the USS Discovery had been co-opted by the governing authorities, who not only placed three operatives aboard the spaceship in suspended animation to secretly deal with the visitor from another star system, but also instructed the ship’s main computer, HAL 9000, to keep the true mission goals from the remaining two “awake” human crew members. In effect, they caused HAL to lie to his fellow astronauts, which created an ultimately fatal conflict for the AI, who was programmed to record and relay all information fully and accurately and could not deal with the contradictions.

Even the first act in 2001 contained a foreshadowing of the direction humanity would one day head in. When the hominid named Moonwatcher, who had learned to hunt and kill in order to survive thanks to the lessons from an alien device that resembled a large black monolith, flung his weapon – an animal bone – towards the sky in a combination of triumph and ecstatic joy, the bone symbolically turned into a spaceship circling Earth. While it was not made explicit in the film at director Stanley Kubrick’s insistence, that first satellite shown was in fact a nuclear weapons platform, along with several others from various nations later shown in that same scene. Then, at the end of the film, when Discovery astronaut David Bowman is transformed by the Monolith ETI into an evolved human called a Starchild who subsequently appears above Earth, the novelization adds that several nations reacted by launching nuclear missiles at the new being. Starchild responded to the attack by deflecting and then detonating the missiles in space with its profound mental powers.

Considered to be not only one of the best science fiction films ever made but also a watershed both for the genre and the cinema overall, 2001: A Space Odyssey was the epitome of the Golden Era of SF films. It combined state-of-the-art production and special effects technologies with a well-written and deep multilevel plot. 2001 also had a very large budget for a science fiction film of its day: Ten million dollars in total, or the equivalent of over 71 million dollars in 2017 currency.

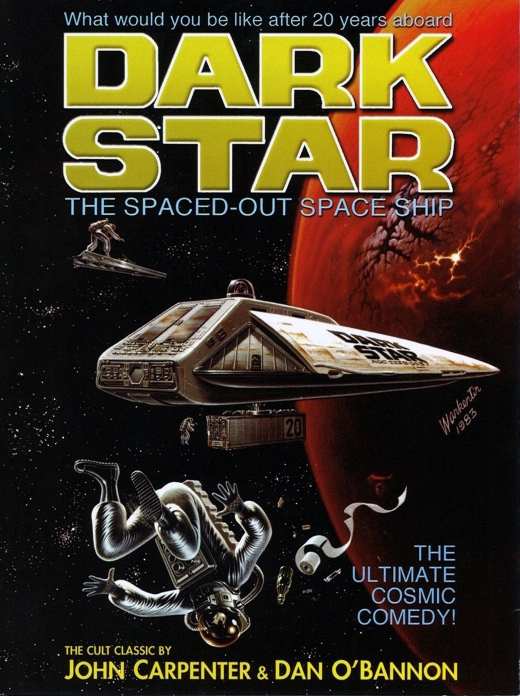

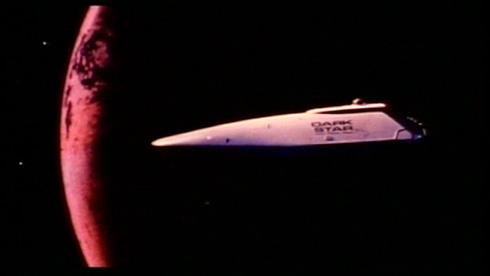

2001 made an important cultural shift in how space exploration was depicted across the entertainment and literary industries which has lasted to the present day. In addition, because the film was so serious and profound in its intent and messages, 2001 also invoked (or perhaps provoked) various satirical imitators. Among the best of those imitators was Dark Star, released into mainstream theaters in 1974, a film with a contrastingly very low budget by any era’s standards which managed to utilize its rather cheap effects and production values to its advantage when it came to telling its story and amusing its audiences. However, while it remains one of the best deliberate 2001 cinematic parodies to date, Dark Star also strongly reflects the general attitude of its era towards space exploration and humanity’s place in the Cosmos, which contrasted and conflicted with the earlier far more positive Manifest Destiny and overall faith in the benefits and progress of science and technology.

As a parody of 2001, Dark Star focused on the less glamorous and appealing aspects of life aboard a long-term deep space mission. 2001 had its share of space ennui on display, but this was certainly not its overriding focus. In the end, 2001 ultimately remained a part of the utopian space vision of the future, whereas Dark Star firmly belongs to the world where manned flights to the Moon ended in 1972 with no definite future plans in sight. There were certainly no serious efforts aimed at building a lunar base or sending a manned mission to Jupiter or any other world in the Sol system. There were two types of space stations in Earth orbit in the early 1970s – the American Skylab and the Soviet Salyut – but both were relatively small experimental hollow cylinders housing only a few astronauts and cosmonauts, respectively, for a matter of months at most. Neither stations were literal jumping off points to the Moon or any other celestial destinations.

On Earth, the major social issues of the late Twentieth Century such as war, racism, poverty, starvation, and class inequality were erupting everywhere, often in violent demonstrations, with those in power no longer able to fully suppress or control those most affected by society’s problems. It seemed rather than technology and science being the saviors of humanity as once touted, they were becoming increasingly responsible for our species’ potential demise by making it easier to harm and kill one another in multiple ways as never before.

In the midst of all this growing unrest, space felt like something remote and unrelated to the lives of the average citizen. Putting humans on the Moon with Project Apollo, once done as a way to display and foster Cold War national pride and geopolitical prestige on a grand scale, was instead being perceived as an extravagant waste of money and resources just so a few elite white military types could bring home some lunar rocks for a small group of scientists. Many thought the space agency received a disproportionate share of federal funding for this “esoteric” pursuit, though in truth the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) took but a small fraction of the government pie compared to most other agencies, a situation that remains to this day.

Many science fiction films of the Golden Era turned their focus away from space and looked inward at these societal problems. Some of the better known examples of this were Soylent Green, The Omega Man, Rollerball, A Clockwork Orange, Solaris, THX-1138, A Boy and His Dog, Zardoz, and the Planet of the Apes franchise. When space was mentioned in these films, it was generally in a negative light, either being aloof from helping with the dysfunctional human problems on the planet or interfering with potential solutions to the highlighted problem. To quote a character labeled Tramp in A Clockwork Orange: “What sort of a world is it at all? Men on the Moon, and men spinning around the Earth, and there’s not no attention paid to earthly law and order no more!”

When space was the focus in these SF films, it was largely there to further the theme that all solutions were to be found by returning to Earth in both the literal and cultural sense. Silent Running (1972) was among the most blatant films on this theme: Humanity had despoiled its home planet so badly through misuse and mismanagement that all remaining plants and animals were preserved in deep space inside biodomes attached to converted freighters. Instead of portraying space as the “savior” of what was left of Earth’s biosphere, the film emphasized that the Final Frontier was a temporary solution at most and certainly not a permanent place for the native organisms of the third world from Sol, including and especially humanity.

Tonight’s Themes for Discussion

Dark Star is indeed a satire, with the occasional venture into outright farce. Being a comedy of sorts does not let it off the hook in regards to having and making some serious and consequential points, even if it does contain an alien that is clearly made from a plastic beach ball with feet from a Halloween costume and produces fart noises, perhaps the basest tool of all humor.

Dark Star is also very existential in nature: The mission to deliberately destroy “unstable” planets is presented as absurd, the crew strive mightily to maintain their individuality in the face of their Sisyphean task, and then there is that wonderful discussion between Doolittle and Bomb 20 about whether or not anything exists outside one’s self, with literally explosive results. Carpenter even described Dark Star as “Waiting for Godot in space,” the 1953 minimalist play by Samuel Beckett about two vagabonds waiting by a dead tree for someone named Godot who never arrives.

So what does this all mean in terms of humanity expanding into space? Does it matter than one film skewers the concept, especially if that film is not well known or appreciated outside of science fiction circles to this very day? Does the message of a film have to affect all of its audience in order to be effective, or just enough of the people who can have an influence on the target of that message? Is there a “Sell by” date for such a film, even one with such seemingly timeless themes?

Did Dark Star contribute to the overall lackluster space efforts of the 1970s after the spectacular achievements and plans of the previous decades? Or did it just reflect the counterculture attitudes of the era? What does it benefit to say that manned space missions might consist of little more than boring and thankless tasks, as well as dangerous and even deadly?

Does Dark Star still have a point in regards to space exploration and colonization 43 years later? Or have times and attitudes changed in regards to space now that governments and their militaries are no longer the sole providers of access to the Final Frontier? Or perhaps Dark Star was showing us the proper way to expand into space without quite realizing it….

Our Story So Far…

This section presents to you my full plot summary of Dark Star. Therefore, I recommend that you watch the film first before following this essay any further in case you have not treated yourself in this manner already, or if you have seen this film but it has been a while since your last viewing and would like a refresher. Dark Star is available on disc and also on YouTube in its theatrical version unedited and unmodified. I have provided the hyperlink to the latter in the “References” section at the end of this piece should you decide to go that viewing route.

According to the opening narration from an early film script version which did not end up in the theatrical release, Dark Star takes place in the middle of the 22nd Century, with several sources pinpointing the year as 2150. Humanity has explored and colonized the Sol system and is now heading out into the wider Milky Way galaxy in what are described as “huge hyperdrive starships: Computer-driven, self-supporting, closed-system spacecraft that travel at mind-staggering post-light velocities. Man has begun to spread among the stars. Enormous ships embark with generations of colonists searching the depths of space for new earths, new homes, new beginnings.”

As may be expected when venturing into unknown realms like outer space, there are dangers in the universe of Dark Star. However, the potential cosmic threat to the human colonists expanding across the galaxy are not the usual marauding aliens but rather unstable exoplanets. Apparently there are enough alien worlds with orbits unsteady enough to one day send them plunging into their primary suns, smash into a moon or other planet, or fling them out of their systems entirely to languish in the bitter cold and dark of the interstellar void that an entire agency has been formed to deal with this problem.

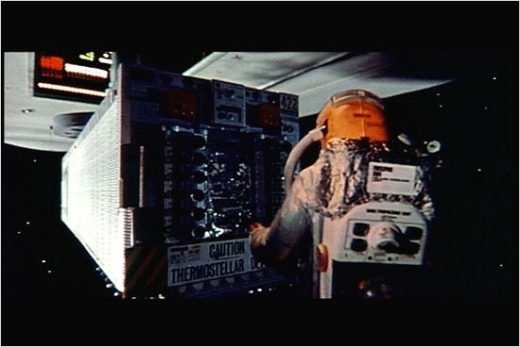

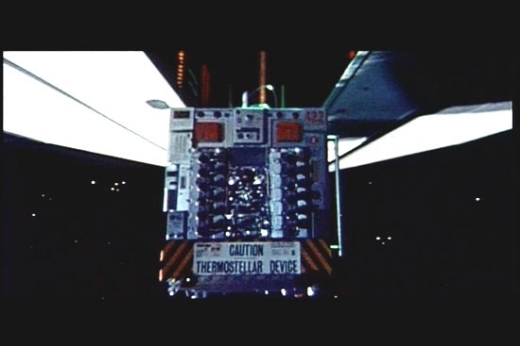

Called the Advance Exploration Corps (AEC), these “special breed of [men]” comb the depths of space in faster-than-light (FTL) scoutships carrying clusters of “chain-reaction bomb[s], otherwise known as an Exponential Thermostellar Device.” Equipped with “sophisticated thought and speech mechanisms, to allow them to make executive decisions in the event of a crisis situation,” these special weapons of massive destruction are capable of obliterating the entirety of an unstable globe, “whose existence poses a threat to the peaceful colonists that follow.”

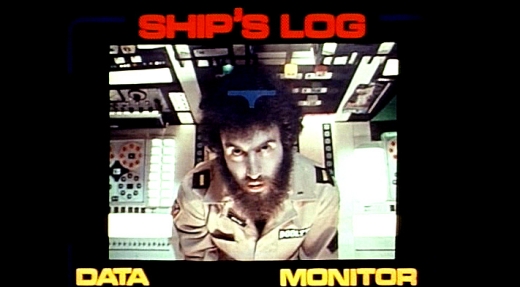

We meet up with one of these scoutships of the AEC called Dark Star (ADC 2239-5531), now in the twentieth year of their mission to “[open] up the farthest frontiers of space.” The crew of the Dark Star is in the process of removing yet another obstacle in humanity’s path of interstellar colonization. Just before we watch these men prepare Bomb Number 19 for its singular destiny, we learn via a transmission from Earth that the ship has recently suffered a loss with the accidental death of its leader, Commander Powell, who was electrocuted by a technical fault with his own command chair.

Once Bomb 19 has successfully and cheerfully completed its task of destroying an unnamed unstable exoplanet, the crew winds down a bit until their next bomb run, this time in the Veil Nebula system. Throughout the story, the audience bears witness to the distinct personalities of each of these men, who are in fact slowly falling apart in parallel with various ship systems after two decades in space. Lieutenant Doolittle, now in charge of the Dark Star, would much rather be back home in Malibu, California, surfing the waves of the Pacific Ocean. Sergeant Pinback constantly attempts to boost the crew’s morale, but only succeeds in making them increasingly resentful and dismissive of him. Boiler appears to be the most content with his job, even gleeful at some points. Talby prefers to spend most of his time in the observation dome at the top of the ship, watching the stars drift by and hoping one day to encounter the mysterious Phoenix Asteroids which he says circle the Universe once every 12.3 trillion years, glowing “with all the colors of the rainbow.”

The crew’s relaxation time is abruptly interrupted by the rather sensual female voice of the ship’s Computer warning them about an approaching asteroid storm that “appears to be bound together by an electromagnetic energy vortex” similar to the one they encountered two years prior. As the Computer’s defensive circuits were destroyed by that previous storm, the crew has to manually activate all of the ship’s defensive systems – within 35 seconds.

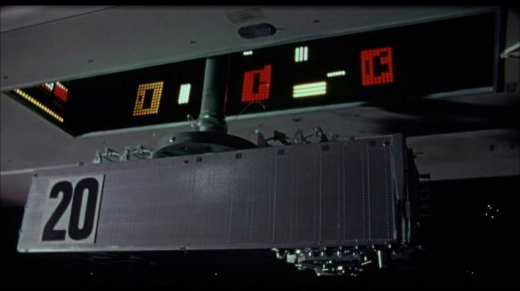

The crew succeeds in placing a protective force field around the Dark Star just before plunging through the asteroid storm, but one stray energy bolt breaches the field and hits the Emergency Airlock at the ship’s stern, damaging Communications Laser Number 17 located inside it, which we later learn “monitors the jettison primer on the bomb drop mechanism.” This causes Bomb Number 20 to receive a very premature operational signal to drop and lowers itself out of the bomb bay during the storm. The Computer informs Bomb 20 that the order was a technical error: Bomb 20 complies and returns to the bomb bay. The Computer attempts to discover the exact source of the problem, but the damaged laser has temporarily inactivated the Computer’s damage tracer circuits.

Later on, Pinback has to go feed the ship’s “mascot”, an alien creature they found while visiting the Magellanic Cloud. The alien, about half as tall as Pinback, resembles a large orange beach ball with two clawed feet. As Pinback is sweeping up the alien’s living area, the creature attacks him and escapes into the depths of the ship. Pinback gives chase, only to be outmaneuvered by the alien and ending up stuck in the ship’s elevator shaft, first hanging from the bottom of the elevator car and later wedged tight in the emergency access hatch in the floor of the elevator itself. Pinback eventually escapes his predicament, but only after he accidentally activates the hatch’s explosive bolts while methodically pressing buttons on the elevator control panel urgently seeking help.

While Pinback is thus preoccupied, the alien roams about the Dark Star, making its way to the damaged communications laser and inadvertently creating even further problems with it. This event causes Bomb 20 to prematurely receive the drop order again and makes ready for its run. Once more the Computer has to convince Bomb 20 not to drop yet, although this time it takes more effort to dissuade the bomb, who states that ignoring the signal to drop runs counter to its programming. Bomb 20 reluctantly returns to the ship’s bomb bay, but declares that “this is the last time” it will ignore the drop signal.

Doolittle and Talby are up in the dome, sharing their dreams about what they would prefer to be doing with their lives. As Doolittle waxes nostalgic about his surf board, Talby receives a general alert about the communications malfunction on his panel readout and informs Doolittle, who merely tells him not to worry about it, that they will “find out what it is when it goes bad.”

Being more concerned about the malfunction than his commander, Talby heads to the Computer Room to determine exactly what the problem is and repair it. Eventually the malfunction is pinpointed to the communications laser damaged earlier. Talby puts on a starsuit and heads down to the Emergency Airlock with a tool kit, informing Doolittle of his plans to fix the laser.

Pinback eventually finds the alien and attempts to render it unconscious with a dart from an anesthetic gun, but instead ends up killing the creature, which reacts to the dart’s impact by explosively releasing gas from its body and flying about the room before landing on the floor completely deflated. Pinback tries to inform Doolittle and Boiler about his battle with the alien as they go to eat lunch, asking how the creature could have been alive “if it was just filled with gas?” Pinback’s companions ignore him as they focus on their meal, which is labeled “ham” but looks instead like packets of multicolored liquid.

Undaunted, Pinback tries to engage the men in a lunchtime discussion about how he isn’t really Sergeant Pinback, but rather a starship Fuel Maintenance Technician named Bill Froug who was mistaken for Pinback after the real astronaut went crazy just before the launch of the Dark Star and jumped “stark naked” into a vat of liquid fuel which Froug was maintaining. Froug attempted to rescue Pinback from the vat by putting on his starsuit for protection and diving in after him, but a member of the launch crew appeared and mistook Froug for Pinback, hurrying him aboard the ship. Froug did not know how to operate the suit’s helmet radio, rendering him unable to explain what had just happened or who he really was.

Doolittle and Boiler barely react to Pinback’s story, except to acknowledge to each other that Pinback had already told them about this four years earlier. We later see Pinback reviewing his personal video diary in private, which confirms his story about being Bill Froug and gives us further examples of how Pinback thinks he has “something of value to contribute to this mission if [the rest of the crew] would only recognize it,” which they clearly do not.

At last the Dark Star arrives at the unstable planet in the Veil Nebula system. As Doolittle, Boiler, and Pinback prepare for this latest bomb run, Talby is in the airlock about to fix Communications Laser Number 17. Talby radios Doolittle in an effort to tell the lieutenant to hold off on dropping Bomb 20 until he can solve the laser issue, but Doolittle is too busy to be bothered and cuts off their communications.

Talby activates the laser’s test mode, making two bright red beams of light shoot across the room. As he attempts to adjust the “cue switch” in the laser mechanism, Talby inadvertently steps into the path of the lasers, becoming temporarily blinded by them and falling to the floor unconscious. His actions create even further damage to both the ship’s Computer and the laser, disrupting the signal that would jettison Bomb 20 away from the ship and towards the target planet.

The rest of the crew discover this rather critical problem when they attempt to drop Bomb 20, which remains attached to the Dark Star – yet still intends to detonate in just over fourteen minutes! Doolittle tries to order the bomb to disarm and return to the bomb bay, but Bomb 20 refuses and states that it will detonate at its programmed time regardless. The damaged Computer is unable to resolve this dilemma, saying that the best it can do is to confine the bomb’s explosion to a radius of one mile using automatic dampers.

Doolittle realizes he has but one final option: To ask Commander Powell what to do.

While Commander Powell was indeed electrocuted by his chair, the crew had placed their leader into a Cryogenic Freezer Compartment in the ship’s Freezer Room, where he remains alive and conscious in a state of “absolute zero,” although Powell’s memory is starting to fade and he is hurt that the crew only visits him when there is a problem they cannot solve themselves.

Talking to Powell through a microphone, Doolittle is able to explain the current situation after some initial difficulty, such as Powell unexpectedly asking Doolittle how a certain Major League baseball team from Los Angeles is doing. “They broke up, they disbanded over fifteen years ago!” replies Doolittle about the Dodgers. “Ah… pity, pity…” says Powell in turn.

Powell initially offers a technical suggestion to stop Bomb 20, the “azimuth clutch,” but Doolittle informs his former captain that it has already been tried without success. The commander then tells Doolittle to talk to the bomb to teach it phenomenology, a field of study which involves the conscious mind and how it relates to the world around it through direct experience.

With just six minutes left before Bomb 20 detonates, Doolittle dons a starsuit with a jetpack and goes outside the ship to speak with the bomb face-to-face, in a fashion. As the two float in space together high above the alien planet, the lieutenant first asks Bomb 20 how it knows it actually exists, to which it replies that this state of being is “intuitively obvious.” Doolittle counters that “intuition is no proof. What concrete evidence do you have that you exist?” Bomb 20 offers the phrase “I think, therefore I am,” made famous by the 17th Century French philosopher René Descartes. Bomb 20 then adds that its collection of various sensors reveal the existence of the outside world to it.

Doolittle explains that Bomb 20’s sensory data “is merely a stream of electrical impulses which stimulate your computing center.” The bomb realizes that since all it knows about the exterior world is what it receives from its electrical connections, it therefore does not “know what the outside universe is like at all, for certain.”

As Bomb 20 now realizes what it thinks it knows about existence may not actually be true, Doolittle moves to the next level of their discussion:

Doolittle: “Now bomb, consider this next question, very carefully. What is your one purpose in life?”

Bomb 20: “To explode, of course.”

Doolittle: “And you can only do it once, right?”

Bomb 20: “That is correct.”

Doolittle: “And you wouldn’t want to explode on the basis of false data, would you?”

Bomb 20: “Of course not.”

Doolittle: “Well then, you’ve already admitted that you have no real proof of the existence of the outside universe.”

Bomb 20: “Yes, well…”

Doolittle: “So you have no absolute proof that Sergeant Pinback ordered you to detonate.”

Bomb 20: “I recall distinctly the detonation order. My memory is good on matters like these.”

Doolittle: “Yes, of course you remember it, but… But all you’re remembering is merely a series of electrical impulses which you now realize have no real definite connection with, with outside reality.”

Bomb 20: “True, but since this is so, I have no proof that you are really telling me all this.”

Doolittle: “That’s all beside the point. I mean, the concept is valid, no matter where it originates.”

Bomb 20: “Hmmm…”

Doolittle: “So if you detonate in…”

Bomb 20: “…9 seconds.”

Doolittle: “You could be doing so on the basis of false data.”

Bomb 20: “I have no proof that it was false data.”

Doolittle: “You have no proof that it was correct data!”

Bomb 20: “I must think on this further.”

To Doolittle’s immense relief, Bomb 20 rises back up into the Dark Star’s bomb bay. While Doolittle and Bomb 20 were having their philosophical discussion, Boiler had the idea to use the ship’s laser rifle to shoot off the support pins holding the bomb so it would drop away. Pinback strongly disagreed with Boiler’s idea, telling him he was a bad shot and would probably end up hitting Bomb 20 instead and setting it off. The two men wrestled and fought for control of the rifle throughout the ship until the Computer informed them that the bomb had returned to its holding area.

As Boiler and Pinback returned to their stations to disarm Bomb 20, Doolittle radios Pinback to ask if he could blow the seal on the hatch to the Emergency Airlock so he can reenter the ship faster than going through the Dorsal Lock he originally emerged from for his spacewalk to Bomb 20. Pinback complies, unaware that Talby is still in the airlock. The sudden release of air from that compartment as the hatch is opened sends Talby shooting out and away from the ship like a rocket, where he tumbles through space without a jetpack to help him return to the Dark Star. Doolittle witnesses this and informs Pinback that he is going off to rescue Talby.

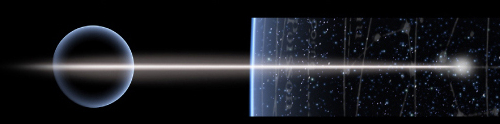

Pinback contacts Bomb 20, telling it to prepare to receive new orders. Bomb 20 replies that the sergeant is “false data.” As the bomb now views everything outside of itself as a lie and a distraction, it thinks the only thing that truly exists is itself. Bomb 20 begins to paraphrase the first lines from the biblical Genesis:

“In the beginning there was darkness, and the darkness was without form and void. And in addition to the darkness, there was also me. And I moved upon the face of the darkness. And I saw that I was alone…. Let there be light.”

A blinding white light suddenly fills the screen. Bomb 20 has detonated, destroying the Dark Star and instantly killing Boiler and Pinback. Commander Powell survives, still encased in a block of ice, tumbling off into the void wondering aloud what had just happened. Doolittle and Talby are pushed away from each other by the explosion in opposite directions (despite Doolittle being on the verge of reaching Talby just before Bomb 20 went off). Doolittle finds himself heading towards the planet they had planned to destroy, with Talby noting that when the lieutenant hits the atmosphere, he will “start to burn. What a beautiful way to die… as a falling star.”

Talby drifts into the Phoenix Asteroids, which just happen to be coming by at that very moment, and is carried off to circle the Universe with them “forever.” Doolittle notices debris from the remains of the Dark Star flying past him. Grabbing a long metal ladder, Doolittle declares “I think I’ve figured out a way” and rides the debris like a surfboard into the planet’s atmosphere. For a brief moment, Doolittle does become a falling star before winking out of existence, while the theme song from the opening credits, “Benson, Arizona,” plays one more time.

As a Film…

Dark Star was one science fiction film I eagerly recall wanting to see after reading about its clever ending with the intelligent talking bomb that thought it was God. I finally had my chance in college with a course examining various science fiction novels and films. I was not disappointed. Dark Star was definitely one of the favorites of the class, which was no small feat as it was shown among other classic and often more renowned cinema of the genre. Then again, Dark Star was most often popular with the college crowds in general, hitting on themes that rose above the usual ones for most mainstream films and being just quirky and “hip” enough to gain its reputation on the college circuit. When I first saw the film, the scene where Doolittle convinced Bomb 20 that nothing existed outside of itself resonated, as in that same semester I had taken an introductory philosophy course which began with that very subject – Cartesian doubt, that is, not talking a literal smart bomb out of blowing up.

Dark Star originated as a project by two University of Southern California (USC) film students, John Carpenter and Dan O’Bannon, who worked on it from 1970 to 1972. O’Bannon played Sergeant Pinback in addition to his other roles and script writer and editor. The film was edited and expanded into its feature length version for release two years later. It was often reported that mainstream audiences did not tend to “get” Dark Star, especially the fact that it was a dark satire on 2001: A Space Odyssey. This is often one of the defining features of most SF films of the Golden Era, aiming above the average audience’s heads and being more widely appreciated only later. Dark Star’s obviously low budget – approximately $60,000, or just over 313K in 2017 dollars – no doubt added to the generally negative viewer response.

Carpenter would go on to have a very successful Hollywood career with some other science fiction films such as Starman (1987) and They Live (1988), but would mostly be known for his groundbreaking work in horror cinema. O’Bannon took his Dark Star scenes with the alien beach ball and greatly expanded upon them into the screenplay for Alien (1979), a very successful SF film (and later a whole franchise) about a very hostile alien creature that gets aboard a commercial starship in deep space and starts killing the hapless crew.

As a science fiction film, I consider Dark Star to still be among the smartest and best of its kind, even over four decades after its general release. This speaks well of the film, but it may also be due to the fact that just three years after Dark Star’s public debut, the first member of the Star Wars franchise arrived on the big screen and culturally body slammed Golden Era type SF films to the sidelines, from which it has yet to fully recover. Smart SF cinema with socially relevant commentary which took precedence over flashy and expensive special effects, already dancing on the margins of Hollywood, was submerged by the arrival of its simpler brethren, which – most importantly for its Tinseltown bosses – generated far more revenue.

Dark Star had a story and message to tell: It wasn’t worried about trying to be everything to everyone like so many mainstream films are today, largely because you have to generate double your film budget from ticket sales in the opening days just to break even. In fact the original incarnations of this film were even more esoteric: The filmmakers had an early scene where the starship crew went to bed after a bomb run and the film literally spent the next five minutes showing the men in their makeshift quarters just sleeping and snoring in the dark! This may not have been quite in the same running in terms of duration with Andy Warhol’s experimental eight-hour film from 1964 titled Empire, where a single camera was aimed at the Empire State Building in New York City and left running, but they are cinematically spiritual brethren.

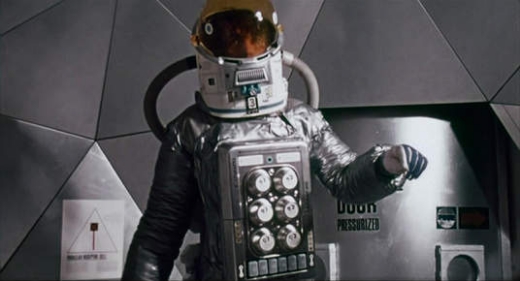

The famous – or infamous, depending on your point of view – inexpensive practical special effects of Dark Star not only did not detract from the story, they actually added to the film’s charm and in most cases looked pretty good, especially when you realize how many SF films in the post-Star Wars era have spent several hundred million dollars to achieve a similar appearance using complex computer graphics, yet they often lack both a deep, intelligent plot and genuine heart in comparison. These are just the key points of the many strong reasons why a remake of Dark Star would not only be unworkable but tantamount to a cultural crime. It is also fun figuring out exactly what was used to make the various props: The cupcake/muffin tin on the front of Talby’s starsuit and the Styrofoam packing material for its backpack, the inverted ice cube trays lit from beneath serving as control panel buttons in the bomb drop control room, the alien that looks like an inflated beach ball because it is an inflated beach ball, and the use of Major Matt Mason action figures as models for certain scenes with Doolittle and Talby in space, which the full-size starsuit designs were based on.

There is even symbolic meaning with some of the special effect choices. The AI bombs look like long-haul truck trailers because they were made from model trailer trucks. This in turn is symbolic of how the scoutship crew is portrayed, not as the brave and noble astronauts exploring the Universe for science and daring adventure as NASA presented to the world, but as a bunch of regular guys just doing the equivalent of an Earth-bound blue-collar job, an occupation that feels unglamorous, pointless, and never-ending, yet they are committed to seeing the task to its completion, if there really is an end point.

Dark Star’s sound effects were rather unique and distinctive: They manage to be serious enough with a flavoring of genre tweak, just like the overall film in general. Playing on the use of electronic music as the presumed sound of the future going back to Forbidden Planet in 1956, the main soundtrack for Dark Star can be seen in the same light as the sounds effects, as both a genuine tribute and an ironic comment on one of the key elements in many science fiction films and television series of its day right to the present. Even more ironic is that the film which Dark Star chiefly satirizes, 2001, actually broke the mold when it came to science fiction cinematic soundtracks, making effective and now legendary use of several classical orchestral pieces: Kubrick deliberately eschewed a more traditional score composed just for it. John Carpenter himself created the Dark Star soundtrack using a modular synthesizer. He also wrote the music for “Benson, Arizona” which played during the opening and closing credit titles.

The humor certainly worked on multiple levels throughout Dark Star: It was smart to have the cast play their roles straight for the most part, even though this idea probably contributed to those audiences who didn’t seem to get the jokes. Science fiction is usually not seen as part of the comedy genre unless it is deliberately and obviously made absurd at slapstick and cartoonish levels. The marketing verbiage of Dark Star often emphasized the film’s comedic aspects (“The Ultimate Cosmic Comedy!”), but it is questionable just how much of that got across to some audiences. I also wonder if other promotional advertising phrases such as “The Spaced Out Odyssey” and “Bombed out in space with a spaced out bomb!” actually helped or only confused and ultimately disappointed early viewers who were expecting a wacky, light, and even psychedelic romp with a bunch of hippy types who would use lots of recreational drugs.

To its everlasting credit, Dark Star did not take the easy and more marketable route, nor did any of the characters ever resort to using drugs or even drink alcohol, which frankly would not have been out of place in a film from the early 1970s. Boiler did smoke a cigar and Pinback held an unlit cigarette briefly when they were relaxing in their makeshift sleeping quarters, but that was the extent. As for the cast often being regarded as hippies, those reviewers are undoubtedly referring to their head and facial hair styles, which were typical for many young white American males of that era, hippy or otherwise.

Like the contemporary attitude on exploring and colonizing space, short hair and a shorn face on a man were considered either to be a relic of an earlier era and/or an indication of a conservative and even militaristic bent, which did not go over well with the counterculture generation. Note the deliberate contrast of the clean-cut military official in the opening scene of Dark Star: He helped to make it obvious who the filmmakers wanted us to root for and who we were to distrust. Of course Doolittle talking about California surfing, Talby getting all mystical about the legendary Phoenix Asteroids, and Commander Powell’s sometimes rambling conversation did play their roles in this perception of the main characters being futuristic descendants of the late 20th Century counterculture.

The quality of the acting was rather well done for the most part, especially considering that the cast were not exactly veterans of the craft and that Dark Star had begun as an even lower budget college film school project. The scenes with the scoutship suddenly stopping when it came out of hyperspace are always amusing, as are the voices and dialogues of Bombs 19 and 20.

On the other hand, the scenes with Pinback and his struggles with the ship’s elevator were often a bit too farcical and went on much too long for my taste; they were clearly meant to pad out the film for mainstream release. Nevertheless, they are now part of the overall film and history of Dark Star, and life carries on. On the plus side, the reason Pinback ended up in this predicament in the first place, his encounter with the alien beach ball mascot, was eventually expanded by Dan O’Bannon into the first and very successful Alien film, which spawned an entire franchise that is now an integral part of our entertainment culture and still churning out films and other products. While I think most of the later films of this franchise were a downgrade in terms of story quality, the entire Alien franchise to date still retains the underlying theme and messages from Dark Star, rendering them a notch above most cinematic SF. Dark Star has also influenced other science fiction media and even some real life events, including the British SF comedy television series Red Dwarf.

Now let’s get down to business….

Same Ship, Different Day

Had Dark Star included the opening narration as written in an earlier script version and presented next, viewers would have found themselves on familiar SF ground:

“It is the mid-22nd Century. Mankind has explored the boundaries of his own solar system, and now he reaches out to the endless interstellar distances of the Universe. He moves away from his own small planetary system in huge hyperdrive starships: Computer-driven, self-supporting, closed-system spacecraft that travel at mind-staggering post-light velocities. Man has begun to spread among the stars. Enormous ships embark with generations of colonists searching the depths of space for new earths, new homes, new beginnings.

“Far in advance of these colony ships goes a new pioneer: The scouts, the pathfinders, a special breed of man who has dedicated his life to blazing the trail through the most distant, unexplored galaxies, opening up the farthest frontiers of space. These are the men of the Advance Exploration Corps. The task they face is one of unbelievable isolation and loneliness. So far from home that Earth is no longer even a point of light in the sky, they must comb the Universe for those unstable planets whose existence poses a threat to the peaceful colonists that follow. They must find these rogue planets — and destroy them. Among these commandos are the men of the scoutship Dark Star.”

This is a well-worn utopian future scenario that goes back to early modern science fiction: Humanity expands into space after conquering all the frontiers on Earth as part of its Manifest Destiny. Once they have settled the Sol system, they look outward to the stars, develop an FTL method of interstellar propulsion, and start exploring and colonizing the rest of the Milky Way galaxy. Adventures ensue and usually humanity dominates the scene despite the odds.

Dark Star throws in a twist on this trope by having an entire space agency devoted to the complete removal of alien planets deemed unsafe for potential colonists by using highly sophisticated and insanely powerful bombs with AI brains to ensure that the task is accomplished. It might have been a lot easier and cheaper to just continually update everyone’s star charts about the state of exoplanets across the galaxy, or even place a beacon satellite in those planets’ version of geosynchronous orbit as an extra layer of warning for any visitors, but then such actions would not be nearly as compelling plot-wise – or as absurd.

Destroying entire worlds in such an utter and violent manner makes two statements: That humans are a dangerous and violent species who will not change their base behaviors and actions even when they reach the stars. The other point being made here is that those in power in such a future will be no different than the rulers we have now, promising a shining future for all while justifying the current sacrifices of certain “undesirable” people and places in the name of progress, safety, and survival.

In our world, governments use their military soldiers to make these often ultimate sacrifices while pushing their particular agendas, which are usually about grabbing territory and resources from rival powers. These soldiers are projected and lauded as brave heroes protecting their homes and families from some terrible enemy, when more often than not they are treated as pawns in a global game of chess.

This cultural viewpoint was certainly well in force when Dark Star was being put together: The Cold War was into its fourth decade, with the threat of nuclear annihilation always seeming to be but the push of a button from becoming a reality. One branch of that era was the Vietnam War, which had done much to jumpstart the counterculture movement and was bitterly argued about and rebelled against on college campuses across America. It does not take much effort to see the analogies with the planet-destroying bombs carried by the Dark Star and the “soldiers” of the AEC carrying out their tasks at the behest of unseen authorities whose only real concern is that their objectives are met.

It is indeed quite the irony to call these interstellar scouts the Advance Exploration Corps when they only explore the galaxy to find planets to blow up as part of an expansionist agenda, not to study for the sake of scientific knowledge. In fact we get no indication that human civilization is doing much of anything in regards to space other than spreading itself to every available alien world for the sake of expanding. Science and technology exist largely to serve this plan, not as any means in themselves. When the ship’s sensors detect a new star right after Bomb 19 destroys its assigned unstable exoplanet, a red dwarf with a system of eight planets, Doolittle inquires if any of these worlds are “any good?” Pinback knows exactly what Doolittle is looking for and replies with “Naah. All stable.”

There are some definite parallels between the mission of the Dark Star and the early Space Age, especially the race to put a “man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth” as President John F. Kennedy first declared before the United States Congress in 1961. While Project Apollo was often touted as humanity finally putting into physical form its ancient desire to reach Earth’s celestial companion and wrest its secrets for science, the main reason such an extraordinary effort took place so soon after the first artificial satellite was placed into orbit had far more to do with Cold War geopolitical posturing than pure science and adventure. Even the start of the Space Age in 1957 was officially declared as part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), but only the most politically naive would have swallowed that claim whole as the real reason Sputnik 1 was circling Earth and beeping its presence to anyone with the proper radio receiver.

The origins of the Space Age itself, despite numerous statements and propaganda to the contrary, were no more “pure” than the real reasons Europeans began venturing to the New Worlds of North and South America. Rulers and politicians then as now, and no doubt into the future, only bankrolled such ventures if there were new lands and riches to be gained. Note how Apollo faded away not long after the United States “won” the Moon race, even though there was still so much of that world to explore for science, and how not a single human being has set foot there again since. Even the number of lunar robotic missions dropped off dramatically after Project Apollo, as many of them were primarily meant as support for the manned conquest of our celestial neighbor. There has been an increase in automated explorers to the Moon in the last decade, but the earlier vision of manned lunar colonies, industrial mining complexes, radio telescopes on the lunar farside, and even vacation hotels remain just visions for now.

Is this what might happen how and when we become a deep spacefaring society? Will we be exploring primarily to serve our expansionist drive? Note how the exoplanet “Holy Grail” for astronomers are alien worlds that most resemble our Earth. The purpose in humanity’s hunt for them is to see if they contain life, since we know our planet best when it comes to which celestial bodies might support organisms.

However, there is also often an underlying theme, especially in popular works on this subject, that these same worlds might be ideal for colonizing some day. At the same time, these writers and often the scientists, engineers, and even managerial and political leaders behind such plans never address (or at least not very loudly) several pertinent issues: If these Earthlike alien worlds can and do support native life, these organisms and their atmospheres may not be compatible with terrestrial life. If this life also happens to be highly intelligent and civilized, then we will be dealing with a whole different range of situations which will complicate any colonization plans, to put it mildly.

It is also ironic that when humans consider the possibility that advanced ETI may have their own ambitions about colonizing the galaxy, they usually do so with the fear that such beings may not be interesting in sharing or otherwise cooperating with us when it comes to our home world and solar system. Yet of course should we wish to colonize an already occupied world or system, such actions are seen as the need for survival, healthy competition, and even an opportunity to “uplift” the natives on the wonders of being human.

Of course all these ideas and concerns remain academic in a world where interstellar vessels of any type are not only conjectural but riddled with significant show-stoppers, be they slower or faster than light speed. Sixty years after the launch of Sputnik 1, humanity has yet to colonize any worlds in their home solar system, let alone those circling another star, or have explorers spend even two years at one shot in low Earth orbit. Methods for robotic interstellar travel and exploration and searching for extraterrestrial intelligences (SETI) are finally starting to be taken seriously, thanks to Breakthrough Initiatives, but how long this effort will last remains to be seen. As with so many other things in our society, support and funding are at the whims of those in power.

It is quite obvious in Dark Star that if the crew of the film’s scoutship represents the thoughts and feelings of the other AEC scoutships spending years scouring the galaxy for unstable planets to destroy, then we have a bunch of workers for humanity’s interstellar civilization ranging from bored to annoyed to indifferent to hostile. Then add on the fact that these folks are in the possession of multiple devices that can individually vaporize an entire world aboard ships that are slowly falling apart with apparently little support from home beyond some hollow rhetoric.

This should make one wonder how many other jobs there are in this interstellar society which have become drudgery for those having to do such work and what effects they are having on them and those people and places around them.

The reactions of Lieutenant Doolittle are a prime example of what can happen to any person who is oppressed even in ways that are not consciously deliberate by others, but societal neglect for the individual in the striving for the “greater good” such as an interstellar colonization effort.

We hear Doolittle plainly state early on that he does not want them to look for “any of that intelligent life stuff. Find me something I can blow up!” when Boiler says there is “a 95% probability of intelligent life in the Horsehead Nebula sector” as they search for their next unstable planet to remove. When they detect a new star, a red dwarf with eight planets, Doolittle only cares if any of them are unstable and has no interest at all in naming the alien sun when Pinback suggests they give it one.

“Commander Powell would have named it,” Pinback replies petulantly. “Commander Powell is dead,” retorts Doolittle, shutting down their brief debate.

Dark Star’s new leader also has nothing but contempt for the beach ball alien they found in the “Magellanic Cloud” and took aboard, nor does he care if there is any intelligent life at their next target in the Veil Nebula. All this is played for laughs on the surface and it does have the desired effect, but one does not have to look too hard to see a man on the verge of becoming even less human than the machines that supposedly serve his purposes, or perhaps suffer an even worse fate.

When we look at the character of Doolittle throughout the film, we do not get the impression of a man who is either cruel or unintelligent. He does seem to care about others and his fondest desire is to go home to Earth and surf. Doolittle even plays a musical instrument of his own design in his off-hours as a way to relieve stress and hold on to his individuality and humanity in the face of an indifferent society and Universe. He is the Everyman for the film audience to relate to, which has its good and bad points in terms of how the viewing public is led to think about space travel and utilization. For Dark Star is certainly no recruiting poster for the space program, and watching the one character who most people would want to relate to show clear indifference to and contempt with the wider Universe does have an effect on the thinking process of its viewing public, even if subconsciously.

Doolittle also clings to the hope that he and the rest of the ship’s crew can go home once they have completed their mission. When Talby tells him how much he enjoys sitting up in the observation dome watching the Cosmos pass by, Doolittle tells Talby he will have “plenty of time later on for staring around.” For Doolittle, the only things he truly misses and wants are “the waves and my board more than anything.” Doolittle would even settle for just having his surfboard with him on the ship so he could wax it once in a while.

Although Doolittle and Talby are roughly equal in terms of intelligence and social standing – which is why they are respectively in charge of the more important areas of the scoutship and their mission – they seem at first glance to have very different ideas and desires about what matters: Talby wants to see the literal Universe and ultimately become a part of the mystical Phoenix Asteroids, while Doolittle wants to go home to Malibu and ride the ocean waves on his surfboard. Of course they are really not that different when you listen to how they talk about their respective dreams, it’s only that Talby’s is a macro vision on a truly cosmic scale, while Doolittle embodies a micro vision confined to one particular place on Earth.

Contrast this with the other two truly living characters of Dark Star, Boiler and Pinback, both of whom represent the so-called “working class.” Boiler appears to be the most content with his situation aboard the ship, or at least the one with the least angst about it all. He relishes blowing up alien planets for the sake of destroying things. We hear no deep, intellectual musings from Boiler, nor even any exterior dreams he might have. No doubt the authorities who sent out these missions would love to have entire crews comprised of Boilers.

Ironically, because Dark Star’s mission is one of bureaucracy and physical labor of a sort and not directly for science and expanding human knowledge, Boiler may have been the one with the best solution to the crisis with Bomb 20 when he suddenly considers getting the Exponential Thermostellar Device away from the ship by using their laser rifle to shoot out the support pins holding Bomb 20 in place, where he says it will fall away and then the crew could presumably hyperdrive to safety in time. It is a seemingly practical and direction solution, if not nearly as entertaining as using Cartesian philosophy to stop Bomb 20 from exploding while still attached to the ship.

However, I do have to wonder how and if the bomb would just “drop away” from the ship if its support pins were removed due to the fact that they were in space, specifically in orbit about a planet. In such a microgravity environment, the bomb would only fall away from the Dark Star if it were also pushed after being separated from the pins which held it to the ship. Perhaps the violent act of shooting off the pins would create such a repulsive force, but would it be enough to get Bomb 20 far enough away for them to survive the impending explosion?

Presumably Boiler would have also needed time to put on a starsuit, since the bomb bay doors were open and exposing the hold to outer space, although putting on such outfits in the mid-22nd Century are apparently a fast and relatively trivial procedure. After all, Pinback was able to quickly don one when he had his one and only encounter with the real Sergeant Pinback, who jumped into a vat of liquid fuel. In comparison, contemporary astronauts and cosmonauts embarking on an extravehicular activity (EVA) or “spacewalk” outside the International Space Station (ISS) require up to two hours to put on their spacesuits and ensure that all is secure before placing themselves in the vacuum of space.

Pinback also strongly expressed concerns that Boiler would miss the support pins and instead shoot Bomb 20, causing it to prematurely detonate. “You’re a bad shot! You’ll hit the bomb! Doolittle’s talking to the bomb…. He’ll save us, you can’t do that!” Pinback shouted at Boiler when the latter declared his intentions. “You don’t know what you are doing!” he later added. Whether Pinback’s concerns about Boiler’s skills as a marksman were justified or he was only expressing his own fears combined with an automatic deference to any and all authority figures along with the potential loss of his only home are subject to debate. One also has to suspect that these thermostellar bombs have a number of features designed to prevent premature detonation from various sources such as a hit from a weaponized laser beam, seeing as they are so incredibly powerful and therefore extremely dangerous. Of course in at least one known case there are some fatal gaps in the system.

Now had Boiler been able to successfully implement his plan, would Bomb 20 have remained on its original countdown schedule even as it presumably fell away from the Dark Star? Might the sudden release of the bomb from the ship cause it to automatically detonate? Or was there a safeguard in place for such a situation? And would there have been enough time for Doolittle to get back into the scoutship, seeing as he had been focused on talking to Bomb 20 and was unaware of the rest of the crew’s own plans?

Of all the crewmen aboard the Dark Star, perhaps the one who had the most to gain both socially and individually by being there was Sergeant Pinback, or rather the person who ended up taking his name and place aboard the ship, Fuel Maintenance Technician Bill Froug. As Pinback explained (several times) to his crewmates, astronaut candidates had to score 700 points on the SAREs for the Officer Corps and he only achieved a 58. Froug was subsequently placed on “liquid fuel maintenance on the launch pad,” where he no doubt might have remained indefinitely until his fateful encounter with the real Pinback.

Although one might wonder how Froug was accepted by the rest of the Dark Star crew at first, assuming they would have trained together and therefore have known each other quite well as real astronauts do for a space mission, Pinback obviously did well enough to eventually learn his counterpart’s role aboard the ship. Perhaps as part of the plot joke and also a reflection on their growing apathy, the rest of the crew did not seem to care much that Froug had taken the place of the real Sergeant Pinback.

Considering that the real Pinback had gone apparently insane and committed suicide by jumping “stark naked” into the vat of rocket fuel that Froug was maintaining, I wonder if he had shown earlier signs of mental instability at least to his crewmates? Did the other men rather callously figure that Froug would make an acceptable if not better Pinback replacement, assuming they had any say in the matter at all once the scoutship headed off into the wider galaxy?

As for the original Sergeant Pinback, was his final act in life the only “sane” response to a mission as insane and absurd as spending decades obliterating whole planets with intelligent bombs just because they might one day become unstable for a permanent human colony to settle upon? Perhaps that is what truly concerned the other crewmembers and they felt it was best to ignore what had happened, lest they too take Pinback’s societal escape route.

Is it better to be alive even in a soulless technologically-dominated society with an equally soulless and ultimately absurd profession in the hope that one day either you or your children will break this cycle to enjoy more meaningful lives? As the narrator proclaimed in the unused beginning of Dark Star, the stated purpose of humanity expanding into the Milky Way galaxy is to find “new earths, new homes, new beginnings,” with the underlying message that better lives will follow with a new mailing address and a change of scenery.

On the surface, Pinback’s efforts to maintain crew morale and order should seem to be of benefit to the overall well-being of the ship almost as important as having enough consumables. However, Pinback is not only woefully inadequate at his self-proclaimed role, it is plainly obvious to his colleagues that Pinback tries to uplift them primarily to improve his own social standing among the crew. He and they know his being aboard the Dark Star was an accident, one that benefits Pinback in one respect, but his social and intellectual limitations ensure that his time with the AEC will be the highlight of what would soon become his truncated life. Ultimately, the best role Pinback can serve is as a suck-up and yes-man to those in authority, the ones who sent them all into the void to spend decades blowing up unfavorable alien worlds. So it becomes little wonder that the rest of the surviving crew resents and disrespects Pinback as much and as often as they do.

When Froug/Pinback complains in his video diary (a prop made from an 8-track tape and a microfiche reader) that the real Sergeant Pinback’s uniforms do not fit him and “the underwear is too loose,” it is not just a comment that the real Pinback was a man physically larger than himself: Pinback/Froug is also revealing that he is literally unfit for the mission, that he cannot metaphorically fit in the man’s shoes or anything else for that matter. Of course in case anyone misses this observation, Pinback/Froug immediately adds to his underwear comment that “I do not belong on this mission and I want to return to Earth.”

Further revelations as to how Pinback’s subsequently overinflated view of himself and his conformist role on the ship follow as we review his video diary, which we learn is programmed to automatically censor curse words and obscene gestures:

“Doolittle says he’s assuming command of this ship [upon the death of Commander Powell] and I say that’s …. I say that he’s exceeding his authority. Because I’m the only one with any objectivity on this ship and I should be the one to assume command! I’m filing a report on this to Headquarters, this is a lot of ….”

“This mission has fallen apart since Commander Powell died! Doolittle treats me like an idiot! Talby thinks he’s so smart. And Boiler punches me in the arm when no one is looking! I’m tired of being treated like an old washrag!”

“I do not like the men on this space ship. They are uncouth and fail to appreciate my better qualities. I have something of value to contribute to this mission if they would only recognize it. Today over lunch I tried to improve morale and build a sense of comradery among the men by holding a humorous round robin discussion of the early days of the mission. My overtures were brutally rejected. These men do not want a happy ship. They are deeply sick and try to compensate by making me feel miserable. Last week was my birthday. Nobody even said Happy Birthday to me. Someday this tape will be played and then they’ll feel sorry.”

Carpenter and O’Bannon played with the image of the space explorer as demigod, cultivated from the earliest days of the Space Age as part of the Cold War agenda to show that the men (and just one woman in the beginning) of their respective superpowers were the finest of what each nation (and ideology) had to offer. This image was still mostly in place when Dark Star premiered: The memories of Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Vostok, Voskhod, and Soyuz were still quite strong, with Apollo and Soyuz continuing with their post-lunar application projects. In essence, astronauts and cosmonauts remained part of that societal image of an elite group of modern-day heroes vaulting themselves into a vast, ancient, and mysterious realm full of wondrous marvels and dangers.

The idea of these space adventurers becoming just regular working Joes doing a job like the majority of the adult population was relegated to a future era when space travel would be considered routine, such as the then-upcoming Space Transportation System (STS), or Space Shuttle program, NASA was promising (but never quite happened as the future turned out). So watching a group of guys who are supposed to be amazing interstellar explorers flying across the galaxy at superlight speeds in the name of science and adventure instead act like a bored, tired, and cranky construction gang who have been at their demolition jobs for too long is simultaneously amusing and concerning for those who thought what they saw on Star Trek and what NASA had been claiming for years were the real blueprints for the future.

The public may have known in their hearts that human beings will remain what makes them human at their cores no matter what they accomplish and where they may go, especially into a realm like space, but they also hoped – fueled by the aforementioned propaganda – that somehow their species would be transformed for the better on multiple levels, yet somehow remain physically the same while also retaining recognizable behavior traits, morals, and goals. Instead, Dark Star told them that humans will be humans, warts and all, no matter where they go or how fast they can get there, so long as the cultural and biological trappings that brought us to where we are now remain essentially the same. If you really do want superheroes in the Final Frontier, then they are going to have to become radically transformed beyond the shiny toys and ships that the comfort food of lesser science fiction stories depict our space future as.

“I thought you were cute”: Aliens in Dark Star

As a general rule, if your science fiction film has aliens in its plot and is a notch above the usual Grade B melodrama, the beings or creatures representing nonterrestrial life forms serve as more than just monstrous villains, if they serve that purpose at all. They can stand in for everything from representing various human social issues to virtual deities and forces of nature, much like the White Whale in Herman Melville’s great novel, Moby Dick, or the alien ocean in Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris. Sometimes they are only hinted at and never directly seen, but can still have a major influence on the story. See Forbidden Planet, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Contact as three prime examples of cinematic ETI who let their technologies be their representatives.

In the case of Dark Star, the aliens on display are a parody of the creatures often found in the lesser grade SF I mentioned. According to a review article on the film written by John Fleming for the December, 1978 issue of Starburst: Science Fantasy in Television, Cinema and Comics (Volume 1, Number 5), which described itself as “Britain’s only media science fiction magazine,” apparently blowing up unstable planets was not the scoutship’s only assignment:

“Part of the original idea was that the crew’s mission included a search for intelligent life. There was to have been a specimen room in the ship: a ‘psychedelic zoo’ with hundreds of bizarre creatures (rather like those which appeared later in the Star Wars canteen). But the cost was too high and the idea was cut back to the one ‘beachball with claws’.”

Yet, with just a little more observing, the aliens which did survive the production’s budget cuts are more than just a genre joke and a way to stretch out the film’s running time.

Did I say aliens plural? Yes I did. Everyone who has seen Dark Star cannot help but remember the beach ball alien taken from the “Magellanic Cloud,” but there was a second known extraterrestrial species aboard the scoutship. When Pinback has to feed the ship’s “mascot” and clean up its makeshift living area in a converted storage room, we see that the beach ball is not alone. Floating behind a translucent wall in the background are four glowing, multicolored creatures of unknown name and origin. Looking like hexagonal-shaped spoked wheels, these aliens silently gravitate towards Pinback, who only responds with an agitated “Get away!” and shoos them off with a gesture. The aliens quickly return to Pinback when he becomes preoccupied with the beach ball alien, who first ignores and then completely forgets about them when the mascot goes on the attack after rejecting its dinner and then escapes into the bowels of the vessel.

We never learn anything of substance about these mysterious creatures, nor are they seen again for the rest of the film. Presumably they were killed when the Dark Star is destroyed by the premature detonation of Bomb 20. On the surface, they serve as an atmospheric filler to the scene, which is appropriate in one respect as the beach ball alien went from existing only in that brief disparaging mention by Doolittle in an early script to eventually have numerous memorable scenes to pad the film with enough running time to be acceptable for wide theatrical release.

Nevertheless, the hexagonal aliens do present the audience with a few tidbits of information about the Dark Star universe: They are proof that some rather exotic extraterrestrial organisms exist and were probably different and interesting enough to the crew that they warranted being brought aboard – no small matter considering the general attitude towards aliens by the men. I wonder if there is a rule that AEC crews are obliged to collect interesting specimens they come across while conducting their main mission? Were these particular aliens rescued from a world that warranted removal under their parameters? Or did Pinback or another crewmember just happen to think they were “cute” like the beach ball alien, or maybe even just “pretty”? Personally I find them to be much more aesthetically pleasing than the beach ball, but far less comically expressive.

As I pondered on whether the hexagonal aliens were truly intelligent or not – the human crew did not seem to think so, seeing as they were in a cage of sorts in a rather dark storage room, though I hesitate to consider them as experts on the subject – another thought occurred to me: These little wagon wheels from some unknown corner of the galaxy reminded me of the Phoenix Asteroids, which we see near the very end of the film looking as Talby first described them, “glow[ing] with all the colors of the rainbow. Nobody knows why. They just glow as they drift around the Universe.” Even the early script version describes the Phoenix Asteroids as “frost-like shapes, expanding and glowing and spinning, slowly refracting all the colors of the spectrum with a cold glow.” Those four little aliens also have a shape similar to frost and snowflakes.

Of course they very likely are not members of the actual Phoenix Asteroids, if for no other reason than Talby would certainly not have allowed them to be kept in such lowly conditions. However, they do share some characteristics, including the question of their being actually “alive” and whether or not they are conscious entities. At the least no one can accuse Dark Star of presenting cinematic aliens which merely resemble humans with mildly exotic prosthetics, a. k. a. actors in rubber suits.

All in all, the hexagonal aliens are pretty intriguing for a collection of “characters” that had no speaking roles and only a few minutes of screen time where they never moved more than a few feet on the set.

As for the beach ball alien, while it may have been initially conceived as a relatively rough joke and time filler, the reluctantly labeled mascot of the Dark Star actually fits in very well with the film being existential in its nature in terms of the absurdity of existence. A thing with the appearance of a large orange balloon with big clawed feet and emits sounds reminiscent of fart noises that is not only alive but smart enough to outwit a human, albeit that human is Pinback. The creature consumes food (and presumably expels bodily waste), has a favorite toy (a rubber mouse), displays curiosity, knows how to use tools and turn them into weapons (the alien effectively turned a broom into a club on Pinback), and even has what could be considered a personality by displaying a range of emotions and reactions despite the lack of anything resembling a face.

Not everyone aboard the scoutship shared such enthusiasm for this extraterrestrial life form, however. Doolittle called it “a damn mindless vegetable [that] looked like a limp balloon. Fourteen light years for a vegetable that went squawk and let a fart when you touch it!” Even Pinback eventually referred to the alien as a “worthless piece of garbage” after it had pushed Pinback to his emotional limits.

When Pinback accidentally dispatches the alien with an anesthetic gun, it is revealed that beneath its orange skin, the creature contained only some form of gas. As a being composed of numerous biological organs among other anatomical features, Pinback naturally asks “how could it live if it was just filled with gas?”

Could creatures exist in the Universe which are little more than a ball of gas? Or glowing, floating hexagons for that matter? Some scientists have speculated that life could evolve from gas and dust in interstellar space, forming helical structures and combining into the fourth state of matter called plasma. At the high end of this hypothetical scale, British astrophysicist Fred Hoyle imagined an ancient, massive, and intelligent version of such a being encountering the Sol system in his 1957 science fiction novel The Black Cloud.

In the case of the beach ball alien, the creature clearly evolved on a planet and not in deep space, but seeing how little we know of the various states of extraterrestrial life at present, it cannot be declared impossible. From the perspective of an ETI with a very different evolution than ours, terrestrial organisms might seem just as improbable to them, possibly even to the point that humans would not be seen as intelligent or even alive by their definition of the word. Hoyle’s intelligent interstellar cloud did not imagine that conscious life could exist on planets until it encountered humanity.

Since existentialism declares the mere existence of reality as fundamentally absurd, the existence of bipedal beings flying around the galaxy blowing up planets they don’t approve of or an orange bag of flatulent gas are not only no less absurd, but therefore no less improbable as a reality by this logic. It certainly gives one both the inspiration and cause to want to seek out these possibilities and also makes us keep an open mind in the process.

In regards to our attitudes on extraterrestrial life, Dark Star does bring up the concerning possibility that as we expand into the galaxy and working and living in space become routine, we may lose that wonder and curiosity about other beings, or only show interest in those life forms which entertain us and/or prove useful to our species in some way. Note how just over two decades ago, the discovery of any exoplanets generated headlines and major excitement across the professional and cultural board. Nowadays, with thousands of confirmed alien worlds, only ones which are considered to be exceptionally bizarre, or relatively close to the Sol system, or appear to be Earthlike – or some combination of all three – warrant public announcement and further attention.

The crew of the scoutship Dark Star, focused on their mission of destruction under the guise of progress and salvation and distracted by such things as the socially destabilizing death of their former commander, the ever increasing number of ship systems failing, and their desire to be anywhere but stuck inside that claustrophobic environment with each other, have become desensitized to such otherwise exciting concepts as alien beings.