Among the many indicators that we have much to learn about brown dwarfs is the fact that we don’t yet know how frequently they form. Recent work from Koraljka Muzic (University of Lisbon) and colleagues has pointed, however, to quite a robust galactic population (see How Many Brown Dwarfs in the Milky Way?). Working with observations at the Very Large Telescope, the study pegged the brown dwarf population at 25 billion, with a potential of as many as 100 billion.

Image: Stellar cluster NGC 1333 is home to a large number of brown dwarfs. Astronomers will use Webb’s powerful infrared instruments to learn more about these dim cousins to the cluster’s bright newborn stars. Credit: NASA/CXC/JPL.

Likewise in need of further data is our understanding of how brown dwarfs form, especially in the region where planet and star overlap. Recall that brown dwarfs are not main sequence stars, as they are not massive enough to ignite hydrogen fusion, even if deuterium and lithium fusion may occur. If we get down to brown dwarfs less than 13 times the mass of Jupiter, are we dealing with planets or stars? And do these objects form as planets (within a circumstellar disk) or as stars (via the collapse of interstellar gas)?

Aleks Scholz (University of St Andrews, UK) will be using the James Webb Space Telescope (assuming successful launch and deployment next year, fingers crossed) to study the cluster in the image above, NGC 1333 in Perseus. A number of brown dwarfs have been located within the cloud, which is itself considered to be a stellar birthing ground for young stars. Usefully, NGC 1333 also appears to contain brown dwarfs at the very low end of the mass distribution.

“In more than a decade of searching, our team has found it is very difficult to locate brown dwarfs that are less than five Jupiter-masses – the mass where star and planet formation overlap. That is a job for the Webb telescope,” Scholz says. “It has been a long wait for Webb, but we are very excited to get an opportunity to break new ground and potentially discover an entirely new type of planets, unbound, roaming the Galaxy like stars.”

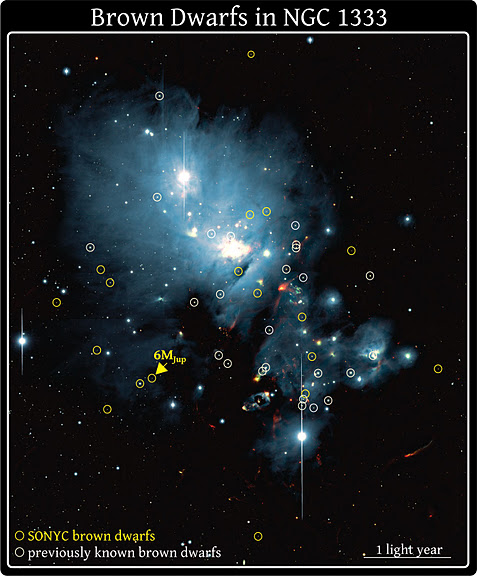

Note the the Substellar Objects in Nearby Young Clusters (SONYC) project, which Scholz leads. The goal is to study the frequency and properties of brown dwarfs in star-forming regions (Koraljka Muzic is part of this collaboration, which also includes Toronto’s Ray Jayawardhana). Below is an image showing brown dwarfs in NGC 1333 as identified by the survey.

Image: Brown dwarfs in the young star cluster NGC 1333. This photograph combines optical and infrared images taken with the Subaru Telescope. Brown dwarfs newly identified by our SONYC Survey are circled in yellow, while previously known brown dwarfs are circled in white. The arrow points to the least massive brown dwarf known in NGC 1333; it is only about six times heftier than Jupiter. Credit: SONYC Team/Subaru Telescope.

Likewise planning to use JWST to address brown dwarf issues is Étienne Artigau (Université de Montréal), who will be looking at an interesting low-mass brown dwarf called SIMP0136. We’ve looked previously at the work Jonathan Gagné (Carnegie Institution for Science) has performed on this one, a brown dwarf whose variability in brightness has been attributed to weather patterns moving into view during its short (2.4 hour) rotation period. Gagné’s team, studying SIMP0136’s membership in a nearby moving group, has pegged its mass at 12.7 Jupiter masses. See Exploring the Planet/Brown Dwarf Boundary for more.

This is an interesting object on a number of counts, not the least of which is the fact that it is a bit less than 20 light years out, making it one of the 100 nearest systems to the Sun. Also noteworthy is the fact that it is a free-floating object not associated with any star, a low-mass brown dwarf on the planet/brown dwarf boundary that in many ways resembles a gas giant. The Webb instrument should be just the ticket for pushing our understanding further.

“Very accurate spectroscopic measurements are challenging to obtain from the ground in the infrared due to variable absorption in our own atmosphere, hence the need for space-based infrared observation. Also, Webb allows us to probe features, such as water absorption, that are inaccessible from the ground at this level of precision,” Artigau explains.

Let’s place SIMP0136 into context, then, as we look toward the next generation of space-based exoplanet work. We know that a potent tool for atmospheric analysis will be transmission spectroscopy, conducted as a planet moves in front of its star as seen from Earth. In SIMP0136, we have an object with gas giant characteristics unhampered by proximity to a star. Artigau goes on to point out in this NASA news item that we can use it to better understand cloud decks in brown dwarf and planet atmospheres as we contrast the two kinds of observation.

One day we’ll have a better idea of how many unbound planetary-mass objects are out there. That they are hard to discover goes without saying, and we’ve only located a few on the brown dwarf/planet boundary. But it’s clear that the attention now being devoted to them through efforts like the Substellar Objects in Nearby Young Clusters project as well as the BANYAN All-Sky Survey-Ultracool (BASS-Ultracool) will, with the aid of space-based instruments, tell us much more. The resource list on the BASS-Ultracool page offers abundant references.

Why so binary? Why not assume a continuum based purely on size? BDs will be more “stellar” or more “planetary” depending on their mass, rather than their classification?

My interests lay in how the continuum of mass plays out in interesting properties and their implications. I would think (naively?) this must be a bountiful area for simulations and confirming them eventually with observations.

Astrophysicists consider a planet to be a brown dwarf based on mass where deuterium fusion begins. Deuterium is believed to be fused into helium three at after 13 Jupiter mass; The core temperature increases the larger the gas giant so that it is over 500, 000 kelvin where deuterium or helium 2 fuses into helium three. To make a star and the fusion of hydrogen into helium one needs 79 Jupiter masses and it becomes a red dwarf star.

Not everyone accepts the 13 Jupiter mass limit, as far as I can see in the literature, at least in terms of marking the boundary between planet and brown dwarf.

Yes and also Isabelle Baraffe and her collaborators have shown that the commonly quoted 13 Jupiter mass lower limit for Lithium burning is misleading as the limit depends on making some simplifications such as composition. If I remember correctly, they showed that a 10 M Jupiter mass object with an iron core can in some cases undergo Lithium burning.

Would be interesting to know the effect Oumuamua might have had on our consciousness had it been a 10 Jovian mass or greater brown dwarf.

…Or any planetary body…

This should also work for planets around Brown Dwarfs:

DIRECT DETECTION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF M-DWARF PLANETS USING LIGHT ECHOES.

“Exoplanets orbiting M dwarf stars are a prime target in the search for life in the Universe. M dwarf stars are active, with powerful flares that could adversely impact prospects for life, though there are counter-arguments. Here, we turn flaring to advantage and describe ways in which it can be used to enhance the detectability of planets, in the absence of transits or a coronagraph, significantly expanding the accessible discovery and characterization space. Flares produce brief bursts of intense luminosity, after which the star dims. Due to the light travel time between the star and planet, the planet receives the high intensity pulse, which it re-emits through scattering (a light echo) or intrinsic emission when the star is much fainter, thereby increasing the planet’s detectability. The planet’s light echo emission can potentially be discriminated from that of the host star by means of a time delay, Doppler shift, spatial shift, and polarization, each of which can improve the contrast of the planet to the star. Scattered light can reveal the albedo spectrum of the planet to within a size scale factor, and is likely to be polarized. Intrinsic emission mechanisms include fluorescent pumping of multiple molecular hydrogen and neutral oxygen lines by intense Ly? and Ly? flare emission, recombination radiation of ionized and photodissociated species, and atmospheric processes such as terrestrial upper atmosphere airglow and near infrared hydroxyl emission. We discuss the feasibility of detecting light echoes and find that under favorable circumstances, echo detection is possible”.

They specifically relate this to use on Proxima Cen b.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.01144

Brown dwarfs also flare and this should work better then with M dwarfs because there is no starlight after the flare subsides.

Substellar brown dwarfs can still pack a star-like punch.

“A brown dwarf was found with “solar” flares that outshine our own sun, despite not making the grade as a star”.

http://www.astronomy.com/news/2016/06/substellar-brown-dwarfs-can-still-pack-a-star-like-punch

Could Ultracool Dwarfs Have Sun-Like Activity?

http://aasnova.org/2016/11/09/could-ultracool-dwarfs-have-sun-like-activity/

K2 Ultracool Dwarfs Survey II: The White Light Flare Rate of Young Brown Dwarfs.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.08745

The temperature increases in proportion to mass in the core because the pressure increase causes the atoms and molecules to vibrate and rotate faster or move faster. Eventually, it gets hot enough for fusion to begin. When the atoms like deuterium and helium three move fast enough and collide, the proton repulsion based on the electromagnetic repulsion between their protons is overcome, and they get close enough for the strong nuclear force to attract them and deuterium fuses into helium three. A gamma ray is emitted in that process, the same thing happens in the proton proton chain fusion process in all stars. The speed is really fast like several hundred kilometers per second and the pressures are enormous.

Pardon me, the deuterium and helium three don’t collide. deuterium collides with a hydrogen atom and becomes helium three which is made of two hydrogen atoms and one neutron. A gamma ray is released in this process, at the end of the 2nd stage of the proton proton chain.

“But it’s clear that the attention now being devoted to them through efforts like the Substellar Objects in Nearby Young Clusters project as well as the BANYAN All-Sky Survey-Ultracool (BASS-Ultracool) will, with the aid of space-based instruments, tell us much more.”

And don’t forget Backyard Worlds (which as it happens Jonathan Gagne is a part of);

https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/marckuchner/backyard-worlds-planet-9

We may have a couple in the pipeline if we’re lucky…

Absolutely, Sam. Thanks for the reminder!

11 January 2018

Text & Graphics:

http://hubblesite.org/news_release/news/2018-03

HUBBLE FINDS SUBSTELLAR OBJECTS IN THE ORION NEBULA

In an unprecedented deep survey for small, faint objects in the Orion Nebula, astronomers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (http://www.nasa.gov/hubble) have uncovered the largest known population of brown dwarfs sprinkled among newborn stars. Looking in the vicinity of the survey stars, researchers not only found several very-low-mass brown dwarf companions, but also three giant planets. They even found an example of binary planets where two planets orbit each other in the absence of a parent star.