Seeing a planet around another star means finding a way to mask the overwhelming glare that swamps the faint image. The job is, as a news release from the American Institute of Physics reminds us, something like trying to see the light of a match held next to an automobile’s headlight from a distance of 100 meters. Consider that the Earth is ten billion times less bright than the Sun at optical wavelengths and you see the enormity of the problem.

Among the possible solutions is an approach taken by Grover Swartzlander and his colleagues at the University of Arizona. Swartzlander eliminates excessive starlight by feeding it through a helical ‘mask’ — a kind of lens. The result is what the team calls an optical vortex coronagraph. From the news release:

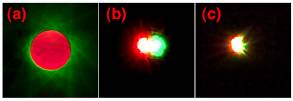

The process works in the following way: light passing through the thicker and central part of the mask is slowed down. Because of the graduated shape of the glass, an “optical vortex” is created: the light coming along the axis of the mask is, in effect, spun out of the image. It is nulled, as if an opaque mask had been placed across the image of the star, but leaving the light from the nearby planet unaffected.

Laboratory trials so far seem promising, with the light from mock stars reduced by factors of 100 to 1000 even as light from the nearby ‘planet’ was unaffected. This image gives some sense of the optical vortex at work.

Laboratory trials so far seem promising, with the light from mock stars reduced by factors of 100 to 1000 even as light from the nearby ‘planet’ was unaffected. This image gives some sense of the optical vortex at work.

Image: These laboratory images demonstrate how the optical vortex coronograph operates. They were obtained with a green “star” and red “planet” (point light sources). (a) shows how the green light is “spun out,” while the red light remains unaffected. Images of the point sources are shown when large (b) and small (c) apertures are used to limit the transmission of light from (a). Credit: Grover Swartzlander, University of Arizona.

For more, a preprint of an article slated to appear in mid-December in Optics Letters is available (PDF warning).