Back in the 1950’s, science fiction magazines were all over the newsstands. That’s significant for Centauri Dreams‘ purposes because these titles spurred many a career in science and a fascination with astronomy, astrophysics and engineering. Many is the scientist I’ve talked to who fondly reminisces about stories that proved inspirational, and in today’s math-challenged world, getting students to start thinking about pursuing work in physics or other sciences is a serious concern.

Which is one reason Paul Raven’s recent essay on the declining fortunes of the science fiction magazines caught my eye. Paul writes Velcro City Tourist Board, the site I turn to when I want to know what’s worth reading on the modern SF scene. He’s well plugged in — Paul writes reviews for Interzone, the fine British magazine, among other things — and for those of us whose SF tastes run to older material, he provides a wonderful way of keeping up with new trends and making sense out of where the field is going.

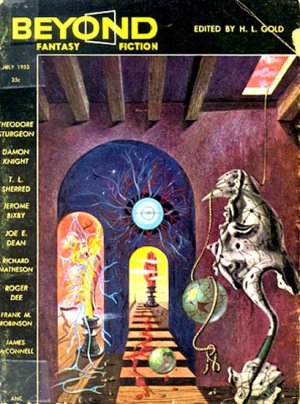

Image: The first issue of Beyond Fantasy Fiction, from July of 1953. Note the distinctive cover art by Richard Powers. The 1950’s produced many solid titles that have long since vanished. What can we do to recapture that era’s publishing vitality?

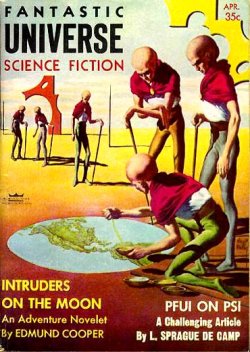

Jump back to that 1950’s newsstand a moment. I can remember seeing, at just one drugstore in suburban St. Louis, a wide range of titles: Galaxy, Infinity, Worlds of IF, Astounding, Venture, Amazing, Fantastic Stories, Fantasy & Science Fiction, Fantastic Universe and Satellite. Others were available around town, some of them only briefly (I recall Damon’s Knight’s Worlds Beyond, for example). And a magazine called Beyond, the fantasy offshoot of Galaxy, is a wonderful memory, its exotic covers capturing fascinating and always well-written tales of the unknown.

Compared to that scene, today’s magazine drought is a sad thing indeed. And even among the survivors, which in the US include Analog (the old Astounding), F&SF and Asimov’s, subscriber numbers are nowhere near what they might be, while the brave attempt to translate short fiction markets to the Web still tries to define itself. I suspect good things will eventually come from that attempt (check Strange Horizons), but until then, I worry like Paul Raven about the effect of genre magazine loss:

The magazine markets have always been the proving ground for new novelists in genre, and that’s the best argument for wanting to them to survive that I can think of. Novels will take much longer to die off in dead tree format for an assortment of reasons – the iconic status of the book, the inconvenience and user cost of printing out a novel length manuscript, and so on – although the big publishers are starting to realise that digital is as unavoidable as death and taxes if they want to stay relevant in a wired world. But magazines of all types are already suffering, because there are so many more efficient ways to get hold of bite-sized content.

Internet content is indeed changing the equation. Is it both the cause of the problem and its solution? The major US magazines are available in digital form through venues like Fictionwise, and as one who does a lot of reading on a Palm TX, I see this as an exploitable market. The key will be figuring out how to turn the necessary profit to support an ongoing venture — writers do like to be paid, and so do editors and publishers.

As the experimentation proceeds, one good thing will be a larger marketplace for writers. The current magazines are largely filled with the same names month after month. The lively market of years past has become a much diminished club of insiders with few membership slots open. Paul believes that free content supported by advertising will reinvigorate the magazine scene and provide new opportunities. Perhaps, but I have my doubts in a world that seems to be turning away from text entirely thanks to the enticement of video in all its venues.

Image: The April 1957 issue of Fantastic Universe. Covers like these prompted endless speculation in this young reader about possible futures and our place in the cosmos.

Even as I write that, though, I’m reminded that one thing I’ve always missed when reading magazines in digital format is not just the illustrations but the advertising itself. I like to look at the cover art of new books, for example, and I miss the print formatting of the paper magazine. The online solution will gradually have to work out file formats (and I am not talking about PDF!) that incorporate as much of the visual appeal of a printed volume as possible, while including the digital benefits that are so obvious, such as the search function. And needless to say, doing this without over-burdening the result with DRM (digital rights management) would allow portability between devices.

The key question persists. As SF magazines make the online transition, will they be able to generate readers in sufficient numbers?

I have no answer to that one, but do believe that a viable science fiction scene is a stimulus to the scientific imagination, and one that acts as a powerful recruiter for many of the sciences. Genre magazines seem like a niche, but their effects have always been greater than their numbers suggest. It’s good to see editors like F&SF‘s Gordon van Gelder engaging on this issue (see the comments to Paul’s post), and searching for the model that will take us forward. Let’s hope such editors succeed.

Don’t fail to check out the work Jim Baen started before his untimely death.

http://www.baens-universe.com/ is an all-electronic quarterly magazine with a range of interests, including fantacy, classic SF, serials, etc.

And of course there’s the 1632-niverse, and the never-ending Grantville Gazette electronic magazines, they’re up to 10, now, with almost entirely new authors writing with professional editors to elevate things well above traditional fanzine levels.

The work Baen has done to make SF available in electronic form, without DRM restrictions, in HTML, Microsoft Reader, Palm/Psion/Window CE, Rocket eBook and good-old RTF is fascinating, and a great way to introduce new readers to the genre – with an entire library of free titles from top selling authors.

This is not a commercial – I’m an avid fan of what Baen (www.baen.com) is doing, and a regular reader of their offerings.

I’m glad you brought Baen into the discussion, Ed. I’ve been hearing what’s going on over there and I particularly like the lack of DRM restrictions. I’ll give the site a look this afternoon, as it’s been some time since I’ve checked it.

All pertinent, and all food for thought, but I’d like to take issue with ONE thing – possibly just slightly out of your context, but it’s something that keeps on popping up in these discussions, and I want to address it – tow wit, you quote Paul Raven as saying:

“The magazine markets have always been the proving ground for new novelists in genre, and that’s the best argument for wanting to them to survive that I can think”

As a natural novelist who writes the OCCASIONAL short story – and submits them to magazines so infrequently as to make it an almost negligible part of my output – I strongly disagree with that. Some of are blessed with being able to write both short and long; some of us DO graduate to novels from short stories and novellas. But the idea that the would-be novelist who hasn’t published a passel of short stories before trying to publish a novel, and who therefore hasn’t “proved” him or herself, is just something I want to squash – there are any number of REALLY successful novelists who haven’t gone the short story-to-novel route.

The way to “prove” yourself in this genre, as in any writing field, is to write well. Short OR long. If you can do both, that’s wonderful – but I would hate to see a potential new SF superstar never get out of the starting gate because his or her natural length lies more in the 90 000 words arena than in crafting 4000-word long short story gems.

As for the magazines being filled with the same names – a couple of things – YES, they are, but those are probably the natural short story writers in the genre – and YES, there could be more names, particularly since I find myself increasingly out of step with the kind of things that ARE published , particularly in the Big Three. I haven’t really read Asimov’s for years, simply because it’s been years since I’ve found a story in there that I am sympatico with. That’s an editorial issue, not a genre one, though. Editors publish what they like, after all.

I’ll continue to send in the occasional short story to the occasional magazine, when one gets written that’s suitable for submission. In the meantime – well – my track record speaks for itself – I’ve published five novels since the turn of the millennium, and have two more under contract which will be appearing over the next two years. I’m a long writer. I plan on writing more LONG works…

Alma, yes, fair enough, and I take your point about long vs. short fiction. Five novels since 2000 is quite impressive — congratulations! Whether they’re proving grounds for longer works or not, though, I still wonder about the best ways of making the digital transition for the magazines, in hopes of opening more markets. In the long run, how such online and other venues impact the novel itself will be a fascinating thing to watch.

In addition to the Internet as a sci-fi venue, I wonder to what degree the Sci-Fi channel could become an outlet. I’m reminded of the Twilight Zone, where Rod Serling assembled and brought to TV the inputs of a number of smaller authors.

Your talk of the decline in people reading jogged my memory about the site Escape Pod(http://www.escapepod.org/) which has its stories, read by actors (at least I assume they’re actors) downloadable as podcasts.

I’m not sure how well marketed they are, but this seems like an extremely smart way of adapting the short story to the media of the current day.

It does of course bring in a bunch of outside factors into the success of a story. A bad reading could kill the beauty of the spoken word, and more experimental texts (experimental at least in terms of how they are laid out on the printed page) would not translate. But it’s definitely a start.

Jonathan’s mention of Escape Pod and Marc’s reference to The Twilight Zone reminds me of Dimension X and X Minus One, the radio plays based on short stories by well known SF authors that ran in the 1950s. Science fiction has numerous venues outside the magazines that equally serve as triggers for interest in the sciences, and a good thing, too, considering how troubled the current publishing scene has become.

Baen’s Universe is up to issue five, it’s been a good read so far.

As for the SkiiFiii Channel, for every decent effort (the two Dune mini-series movies, Battlestar Galactica), you get about a dozen bombs (Mansquito, anyone?).

I keep hoping that they put on a SF/science-related talk show. Alas, instead we get wrestling.

For me one of the saddest things about the passing of the scifi pulps and magazines will be the end of collecting. I remember the thrill of discovering a trunk filled with old moldy, yellowing old pulps and comics in an uncle’s attic one summer. That’s never going to happen with material published online. And finding stuff on someone’s hard drive just isn’t the same. The sense of tradition that’s been part of scifi culture for almost 80 years will end. So I’m definitely not one of the cheerleaders of the new internet order, though I accept that it’s pretty much inevitable.

Chris, you’ve struck a chord, particularly as I look at my 1930s Astoundings and all the 50s-era stuff I still have around here. Collecting the old issues is one of life’s great enjoyments, and we’re losing all that.

Fred Kiesche

As for the SkiiFiii Channel, for every decent effort (the two Dune mini-series movies, Battlestar Galactica), you get about a dozen bombs (Mansquito, anyone?).

I wonder what the ratio of good to bleh stories was in the pulp era? 90% of everything is crap the man said ..

Just remember that enough manure can sometimes make

some very pretty flowers bloom.

If your audience is wide enough, simple non-offensive ads from Google’s Adsense alone can sustain a very decent income for writing. There are alternative forms to publishing science fiction (or any content) in the online medium which can generate a wide audience. Blogs are very popular example.

There are many subtle configuration requirements to get Adsense to generate better income. I’ve seen two very similar sites in both traffic and content, both with Adsense ads, one earning $250 a month, and the other earning $6500 per month. Both had about 300,000 visitors a month. The difference was the placement and configuration of the ads and how the content of the site was configured.

Content sites can generate a lot of advertising revenue done right. Although, to some degree it depends on the content. First, if the quality of the content is not good enough to attract a large audience, it won’t be effective. Second, if the content subject matter doesn’t generate interesting (and high paying) ads, that will reduce its effectiveness despite popularity. I’m sure it took a long time for magazine publishers to figure out what was effective to balance advertising with the real content. The same evolution is occurring in the online medium.

Think outside the box. I’m sure there are a number of different approaches to publishing science fiction content which could be better than simply throwing out an entire book with or without DRM. Baen is definitely a pioneer in exploring the possibilities. The 1632/Flint series has definitely exemplified some of the possibilities. Isn’t exploring the possibilities a significant part of what science fiction is all about?

“As for the SkiiFiii Channel, for every decent effort (the two Dune mini-series movies, Battlestar Galactica), you get about a dozen bombs (Mansquito, anyone?).”

Agreed. My wife and I gave up on made-for-sci-fi-channel movies a long time ago. Mansquito was a deciding factor in this.