A flattened envelope of gas and dust surrounding the young protostar L1157 gives us some idea of what our Solar System may have looked like as it began to form. The object is only a few thousand years old, the central star hidden, with its envelope detectable in silhouette as a black bar. The view from the Spitzer Space Telescope (below) shows how infrared can look within the dust to see structure. While the telescope cannot penetrate the envelope (itself hard to see in this image), enormous jets whose hottest points appear in white are clearly defined.

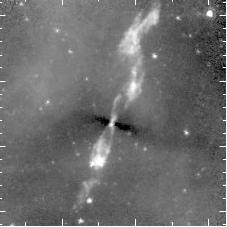

These jets are interesting. They’re being emitted from the protostar’s two magnetic poles, and are approximately one and one half light years from end to end. The envelope of material is too thick for Spitzer to penetrate and appears in black, its thickest part visible as a black line crossing the jets. The envelope is roughly centered on the polar jets and perpendicular to them, showing up more clearly in the grayscale image below, which is drawn from the paper soon to be published on this work.

Image (above): A rare, infrared view of a developing star and its flaring jets taken by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope shows us what our own solar system might have looked like billions of years ago. In visible light, this star and its surrounding regions are completely hidden in darkness. The color white shows the hottest parts of the jets, with temperatures around 100 degrees Celsius. Most of the material in the jets, seen in orange, is roughly zero degrees on the Celsius and Fahrenheit scales. The reddish haze all around the picture is dust. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UIUC.

The collapsing cloud that will give rise to this system rotates faster as it coalesces, the growing magnetic field ejecting some of the gas and dust along the magnetic axis. Leslie Looney (UIUC) notes the significance of the jets: “If material was not shed in this fashion, the protostar’s spin would speed up so fast it would break apart.”

Image: This grayscale view of L1157 makes the presence (and size) of the surrounding envelope more apparent. Credit: Leslie Looney/UIUC.

Some 800 light years from Earth in the constellation Cepheus, L1157 appears black in visible light but infrared reveals the structures that should one day produce planets around this star. But keep the scale in mind. Although L1157 will one day be a star of about solar mass, the envelope of gas and dust around it is huge, big enough to hold tens of thousands of solar systems like ours. What will eventually become a planet-forming disk would be in the first photograph smaller than a pixel.

The paper is Looney, Tobin et al., “A Flattened Protostellar Envelope in Absorption around L1157,” accepted for publication in Astrophysical Journal Letters and available online.

Vertical Shearing Instabilities in Radially Shearing Disks: The Dustiest Layers of the Protoplanetary Nebula

Authors: E. Chiang (UC Berkeley)

(Submitted on 28 Nov 2007)

Abstract: Gravitational instability of a vertically thin, dusty sheet near the midplane of a protoplanetary disk has long been proposed as a way of forming planetesimals. Before Roche densities can be achieved, however, the dust-rich layer, sandwiched from above and below by more slowly rotating dust-poor gas, threatens to overturn and mix by the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability (KHI). Whether such a threat is real has never been demonstrated: the Richardson criterion for the KHI is derived for 2-D Cartesian shear flow and does not account for rotational forces. Here we present 3-D numerical simulations of gas-dust mixtures in a shearing box, accounting for the full suite of disk-related forces: the Coriolis and centrifugal forces, and radial tidal gravity. Dust particles are assumed small enough to be perfectly entrained in gas; the two fluids share the same velocity field but obey separate continuity equations. We find that the Richardson number Ri does not alone determine stability. The critical value of Ri below which the dust layer overturns and mixes depends on the height-integrated metallicity Z (surface density ratio of dust to gas). Nevertheless, for Z between one and five times solar, the critical Ri is nearly constant at 0.1. Keplerian radial shear stabilizes those modes that would otherwise disrupt the layer at large Ri. If Z is at least 5 times greater than the solar value of 0.01, then midplane dust densities can approach Roche densities. Such an environment might be expected to produce gas giant planets having similarly super-solar metallicities.

Comments: ApJ, in press. Connections made to baroclinic instability. Movies available at this http URL

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0711.4349v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Eugene Chiang [view email]

[v1] Wed, 28 Nov 2007 17:45:29 GMT (547kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0711.4349

Three-Dimensional Simulations of Kelvin-Helmholtz Instability in Settled Dust Layers in Protoplanetary Disks

Authors: Joseph A. Barranco (San Francisco State University)

(Submitted on 28 Nov 2007)

Abstract: As dust settles in a protoplanetary disk, a vertical shear develops because the dust-rich gas in the midplane orbits at a rate closer to true Keplerian than the slower-moving dust-depleted gas above and below. A classical analysis (neglecting the Coriolis force and differential rotation) predicts that Kelvin-Helmholtz instability occurs when the Richardson number of the stratified shear flow is below roughly one-quarter. However, earlier numerical studies showed that the Coriolis force makes layers more unstable, whereas horizontal shear may stabilize the layers. Simulations with a 3D spectral code were used to investigate these opposing influences on the instability in order to resolve whether such layers can ever reach the dense enough conditions for the onset of gravitational instability. I confirm that the Coriolis force, in the absence of radial shear, does indeed make dust layers more unstable, however the instability sets in at high spatial wavenumber for thicker layers. When radial shear is introduced, the onset of instability depends on the amplitude of perturbations: small amplitude perturbations are sheared to high wavenumber where further growth is damped; whereas larger amplitude perturbations grow to magnitudes that disrupt the dust layer. However, this critical amplitude decreases sharply for thinner, more unstable layers. In 3D simulations of unstable layers, turbulence mixes the dust and gas, creating thicker, more stable layers. I find that layers with minimum Richardson numbers in the approximate range 0.2 — 0.4 are stable in simulations with horizontal shear.

Comments: 33 pages, 11 figures (5 color, low-resolution versions), Submitted to The Astrophysical Journal, see this http URL for higher resolution color figures and associated avi animation files

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0711.4410v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Joseph Barranco [view email]

[v1] Wed, 28 Nov 2007 02:47:35 GMT (341kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0711.4410

Debris Disks Around Nearby Stars with Circumstellar Gas

Authors: Aki Roberge, Alycia J. Weinberger

(Submitted on 28 Nov 2007)

Abstract: We conducted a survey for infrared excess emission from 16 nearby main sequence shell stars using the Multiband Imaging Photometer for Spitzer (MIPS) on the Spitzer Space Telescope. Shell stars are early-type stars with narrow absorption lines in their spectra that appear to arise from circumstellar (CS) gas. Four of the 16 stars in our survey showed excess emission at 24 microns and 70 microns characteristic of cool CS dust and are likely to be edge-on debris disks. Including previously known disks, it appears that the fraction of protoplanetary and debris disks among the main sequence shell stars is at least 48% +/- 14%. While dust in debris disks has been extensively studied, relatively little is known about their gas content. In the case of Beta Pictoris, extensive observations of gaseous species have provided insights into the dynamics of the CS material and surprises about the composition of the CS gas coming from young planetesimals (e.g. Roberge et al. 2006). To understand the co-evolution of gas and dust through the terrestrial planet formation phase, we need to study the gas in additional debris disks. The new debris disk candidates from this Spitzer survey double the number of systems in which the gas can be observed right now with sensitive line of sight absorption spectroscopy.

Comments: 10 pages including 4 figures. Accepted for publication in ApJ

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0711.4561v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Aki Roberge [view email]

[v1] Wed, 28 Nov 2007 19:26:16 GMT (115kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0711.4561

Observational Tests of Planet Formation Models

Authors: A. Sozzetti (1,2), G. Torres (1), D.W. Latham (1), B.W. Carney (3), J.B. Laird (4), R.P. Stefanik (1), A.P. Boss (5), D. Charbonneau (1), F.T. O’Donovan (6), M.J. Holman (1), J.N. Winn (7) ((1) CfA, (2) OATo, (3) UNC, (4) BGSU, (5) CIW, (6), NASA Goddard, (7) MIT)

(Submitted on 30 Nov 2007)

Abstract: We summarize the results of two experiments to address important issues related to the correlation between planet frequencies and properties and the metallicity of the hosts. Our results can usefully inform formation, structural, and evolutionary models of gas giant planets.

Comments: 2 pages, no figures. To appear in the proceedings of “IAU conference 249: Exoplanets: Detection, Formation and Dynamics”, held in Suzhou, China, 22-26 Oct. 2007

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0711.4901v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Alessandro Sozzetti [view email]

[v1] Fri, 30 Nov 2007 11:00:50 GMT (16kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0711.4901

From discs to planetesimals I: evolution of gas and dust discs

Authors: Richard Alexander

(Submitted on 3 Dec 2007)

Abstract: I review the processes that shape the evolution of protoplanetary discs around young, solar-mass stars. I first discuss observations of protoplanetary discs, and note in particular the constraints these observations place on models of disc evolution. The processes that affect the evolution of gas discs are then discussed, with the focus in particular on viscous accretion and photoevaporation, and recent models which combine the two. I then discuss the dynamics and growth of dust grains in discs, considering models of grain growth, the gas-grain interaction and planetesimal formation, and review recent research in this area. Lastly, I consider the so-called “transitional” discs, which are thought to be observed during disc dispersal. Recent observations and models of these systems are reviewed, and prospects for using statistical surveys to distinguish between the various proposed models are discussed.

Comments: 28 pages, 9 figures. Refereed review chapter for proceedings of VLTI summer school on “Circumstellar discs and planets at very high angular resolution”, to appear in New Astronomy Reviews. See this http URL for more details

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0712.0388v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Richard Alexander [view email]

[v1] Mon, 3 Dec 2007 21:02:08 GMT (223kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0712.0388