Centauri Dreams‘ rarely spends time close to the Sun, preferring to focus on stars other than our own, and their planets. But the MESSENGER spacecraft’s close pass by Mercury, leading eventually to orbit, does have an interstellar connection in the person of project scientist Ralph McNutt, who is prominent not only in exploring the closest planet to Sol but also in planning a mission that would be our farthest yet, the Innovative Interstellar Explorer attempt to study nearby interstellar space.

Fire and ice. McNutt (Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory) obviously enjoys working at the extremes, and one hopes for an outcome for IIE just as successful as MESSENGER has enjoyed thus far. Meanwhile, Mercury looks more or less as expected, but don’t let that fool you. As Greg Laughlin points out at his systemic site, we’re looking at vast stretches of terrain that have never before been seen, our earlier views of Mercury having been delivered by Mariner 10 flybys that saw only parts of this world.

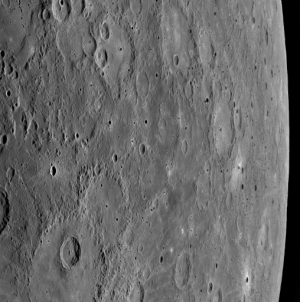

Image (click to enlarge): Just nine minutes after the MESSENGER spacecraft passed 200 kilometers (124 miles) above the surface of Mercury, its closest distance to the planet during the January 14, 2008 flyby, the Wide Angle Camera (WAC) on the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) snapped this image. The WAC is equipped with 11 different narrow-band filters, and this image was taken in filter 7, which is sensitive to light near the red end of the visible spectrum (750 nm). This view, also imaged through the remaining 10 WAC filters, is from the first set of images taken following MESSENGER’s closest approach to Mercury. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Does any of this remind you of the poignancy that accompanied the Voyager images from Neptune? In that case, we were looking at the last planetary discoveries the Voyager mission would make before the two spacecraft set forth into the outer reaches, where they still perform helpful science. In this case, we’re looking at the last rocky, ‘terrestrial’ class world we haven’t visited in our Solar System. Laughlin, always an elegant writer, catches the excitement of such discovery perfectly:

Nevertheless, we do gain something extraordinary whenever a new vista onto a terrestrial world is opened up. Galileo was the first to achieve this, when he turned his telescope to the Moon and saw its three-dimensional relief for the first time. Mariner 4 and Mariner 9 accomplished a similar feat for Mars. The Magellan spacecraft revealed the Venusian topography. And once Messenger has photographed the full surface of Mercury, there will be a profoundly significant interval before we get our next up-close view of an unmapped terrestrial planet. My guess is that it’ll be Alpha Centauri B b.

Just how significant that interval will be is, of course, unknown, for by ‘up-close,’ I assume Laughlin is talking about imagery from a probe within the Centauri system, a feat we are many decades (at least) away from achieving. Meanwhile, we do have New Horizons, taking us out to the icy worlds of Pluto and Charon and on into the Edgeworth/Kuiper belt.

Doubtless there are still surprises in the deep ranges of that belt, perhaps even a few rocky worlds displaced from inner orbits during the earliest stages of our system’s formation (see the comments on the systemic post for more). But if they are there, New Horizons is unlikely to stumble upon one, nor would it be able to view such a world closely if it did. I think Laughlin is right: Our next detailed look at an unmapped terrestrial planet will take place among the Centauri stars, unless they defy the growing odds and turn out to have no planets at all.

I wonder how many worlds in our solar system qualify as terrestrials: Mercury, Venus, the Earth and Mars are the traditional ones, but if you relax certain conditions such as the requirement to be traditional planets, you can add the Moon, Io and Europa (probably more like a terrestrial planet with a global ocean than an “ocean world” or ice planet, which has a significant icy mantle), perhaps Vesta too…

andy: You could stretch that out to potential Earth-type worlds that could be moons of extra-solar gas giant planets.

Would it be a moon, or planet?

I think such pre-conditions would need to be relaxed.

dad2059: I’m not entirely sure such a distinction is worthwhile. Surely the term “planet” depends on the context you use it in… a discussion of the properties of terrestrial planets probably should consider the Moon, Io and Europa, so for the purposes of such a discussion why not consider them planets? If you want to find out about the overall dynamics of the solar system, they are clearly not so important, so in such a discussion it isn’t worth calling them planets. I’m not a fan of applying rigid definitions to terms which are merely relatively arbitrary subsets of a vast continuum of objects.

Have any flyby anomalies been detected?

Hi All

The gravitationally dominant object in a certain orbit is, I think, part of the current definition of “planet” – thus Pluto’s demotion. Moons will always be moons, as they’re always the secondary bodies, but to anyone living on them they will be “the World” or “earth”.

“Planet” once meant the objects that moved relative to the fixed stars, thus the Moon and Sun qualified, but – oddly – Earth didn’t, as it supposedly didn’t move. We now know better. Once we survey a few more solar systems perhaps we will know what to call habitable moons.

Eric, no word on flyby anomalies at this point, but it will be intriguing to see if any turn up. I also note a paper titled “Can the flyby anomalies be explained by a modification of inertia?”:

http://arxiv.org/abs/0712.3022

from the recent BIS session; Larry also linked to it this morning.

None of the major asteroids have yet been seen close-up, I expect there will be a few surprises, particularly with Ceres.

This article in the latest online Sky & Telescope newsletter

shows an image of Mercury taken from Earth that matches

well with what MESSENGER has seen:

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/observing/objects/planets/14029937.html

Mercurian impact ejecta: Meterorites and mantle

Authors: B. Gladman, J. Coffey

(Submitted on 25 Jan 2008)

Abstract: We have examined the fate of impact ejecta liberated from the surface of Mercury due to impacts by comets or asteroids, in order to study (1) meteorite transfer to Earth, and (2) re-accumulation of an expelled mantle in giant-impact scenarios seeking to explain Mercury’s large core.

In the context of meteorite transfer, we note that Mercury’s impact ejecta leave the planet’s surface much faster (on average) than other planet’s in the Solar System because it is the only planet where impact speeds routinely range from 5-20 times the planet’s escape speed. Thus, a large fraction of mercurian ejecta may reach heliocentric orbit with speeds sufficiently high for Earth-crossing orbits to exist immediately after impact, resulting in larger fractions of the ejecta reaching Earth as meteorites.

We calculate the delivery rate to Earth on a time scale of 30 Myr and show that several percent of the high-speed ejecta reach Earth (a factor of -3 less than typical launches from Mars); this is one to two orders of magnitude more efficient than previous estimates. Similar quantities of material reach Venus.

These calculations also yield measurements of the re-accretion time scale of material ejected from Mercury in a putative giant impact (assuming gravity is dominant). For mercurian ejecta escaping the gravitational reach of the planet with excess speeds equal to Mercury’s escape speed, about one third of ejecta re-accretes in as little as 2 Myr. Thus collisional stripping of a silicate proto-mercurian mantle can only work effectively if the liberated mantle material remains in small enough particles that radiation forces can drag them into the Sun on time scale of a few million years, or Mercury would simply re-accrete the material.

Comments: 14 pages. Submitted to Meteoritics and Planetary Science

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0801.4038v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Brett Gladman [view email]

[v1] Fri, 25 Jan 2008 22:10:37 GMT (640kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0801.4038

Chaotic diffusion in the Solar System

Authors: Jacques Laskar

(Submitted on 22 Feb 2008)

Abstract: A statistical analysis is performed over more than 1001 different integrations of the secular equations of the Solar system over 5 Gyr. With this secular system, the probability of the eccentricity of Mercury to reach 0.6 in 5 Gyr is about 1 to 2 %. In order to compare with (Ito and Tanikawa, 2002), we have performed the same analysis without general relativity, and obtained even more orbits of large eccentricity for Mercury. We have performed as well a direct integration of the planetary orbits, without averaging, for a dynamical model that do not include the Moon or general relativity with 10 very close initial conditions over 3 Gyr. The statistics obtained with this reduced set are comparable to the statistics of the secular equations, and in particular we obtain two trajectories for which the eccentricity of Mercury increases beyond 0.8 in less than 1.3 Gyr and 2.8 Gyr respectively.

These strong instabilities in the orbital motion of Mecury results from secular resonance beween the perihelion of Jupiter and Mercury that are facilitated by the absence of general relativity. The statistical analysis of the 1001 orbits of the secular equations also provides probability density functions (PDF) for the eccentricity and inclination of the terrestrial planets.

Comments: 17 pages, Accepted in Icarus

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0802.3371v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Jacques Laskar [view email]

[v1] Fri, 22 Feb 2008 19:32:12 GMT (2069kb,D)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0802.3371

Will Mercury Hit Earth Someday?

April 24, 2008by Ken Croswell

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/news/home/18103199.html

Mercury as seen by Messenger on January 14, 2008, from about 17,000 miles away. Might this inner-solar-system body someday destroy all life on Earth? Perhaps.

NASA / JHU-APL / Carnegie Inst. of WashingtonFirst, the bad news: the inner solar system is unstable. Given enough time, Jupiter’s gravity could yank Mercury out of its present orbit.

Two new computer simulations of long-term planetary motion — one by Jacques Laskar (Paris Observatory), the other by Konstantin Batygin and Gregory Laughlin (University of California, Santa Cruz) — have both reached the same disturbing conclusion.

Says Laughlin, “The solar system isn’t as stable as we’d thought.” Both teams have found that Jupiter’s gravity can increase Mercury’s orbital eccentricity over time. Mercury’s path around the Sun is already nearly as elliptical as Pluto’s. But Jupiter can make Mercury’s orbit so out of round that it overlaps the path of Venus. A close encounter between them could send the innermost planet careening off wildly.

“Once Mercury crosses Venus’s orbit,” Laughlin says, “Mercury is in serious trouble.”

So is Earth.

At that point, the simulations predict Mercury will suffer generally one of four fates: it crashes into the Sun, gets ejected from the solar system, it crashes into Venus, or — worst of all — crashes into Earth.

To call this catastrophic is a gross understatement. Such an impact would kill all life on our planet. Nothing would survive. By contrast, the asteroid that doomed the dinosaurs 65 million years ago was likely just 6 miles in diameter; Mercury is 3,032 miles across. The last time an object about that size hit the Earth, the resulting debris formed our Moon.

Think we’ll escape the chaos by fleeing to Mars? Think again. Even Mars might not be safe. In one of the computer simulations, the Red Planet was tossed into the cold of interstellar space.

Now, the good news: there’s only about a 1% chance that Mercury will go crazy before the Sun bloats into a red giant billions of years from now. “If you’re an optimist,” says Laughlin, “then you say the glass is 99 percent full.”

Laskar, who discovered that Mercury could go wild back in 1994, will publish his paper in Icarus; Batygin (who’s still an undergraduate) and Laughlin will publish theirs in The Astrophysical Journal.