I recently wrote about EPOXI, the dual-purpose extended mission being flown by the Deep Impact spacecraft. Yes, this is the same spacecraft that delivered an impactor to comet Tempel 1 with such spectacular results back in 2005. The vehicle now proceeds to a flyby of comet Hartley 2, but along the way a second extended mission has been coaxed out of it, this one targeting several known transiting planets in a search for signs of undiscovered worlds in those same systems. The mission will also look for possible moons or rings around the giant planets already discovered.

Another goal: To study the Earth, by way of calibrating the kind of ‘pale blue dot’ imagery a future terrestrial planet finder might see. In fact, observations taking place this very day should be helpful because the Moon will ‘transit’ the Earth from the spacecraft’s perspective.

And yes, the nomenclature is confusing, but acronyms are the name of the game in space operations. EPOXI is actually a conflation of two other acronyms: DIXI is the Hartley 2 mission ((Deep Impact Extended Investigation), while the extrasolar observations operate under the name EPOCh (Extrasolar Planet Observation and Characterization).

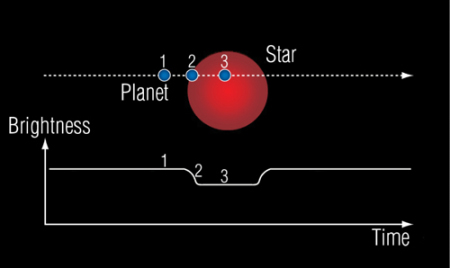

Image: During the EPOCh phase, the spacecraft will observe known transiting planets. This graphic shows approximately what we expect to see as the planet begins to cross in front of its parent star and how the light coming from that star will slightly lessen because the planet is blocking a little bit of the light. The details of the light curve — how deep the dip is, how wide, how steep the drop off — reveal subtle clues about the planet. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UMD/GSFC

The Hartley 2 encounter is scheduled for October, 2010, but the EPOCh work has been underway since late January. According to principal investigator Drake Deming, the most recent observations have focused on the red dwarf GJ 436, known to be orbited by a Neptune-class planet whose eccentric orbit may be caused by gravitational effects from a second planet, possibly with a mass comparable to that of Earth, and in an orbital period ranging from twenty to thirty days. It is conceivable that such a planet would fall within this small star’s habitable zone (but see below), making any transit measurements quite helpful, since EPOCh can detect transiting planets as small as half the size of Earth.

Absent a transit of a new planet, though, EPOCh can still study the known planet to collect further data about its orbital perturbations. Transits are useful not only for discovery purposes, but because they can help us peg the length of the planet’s orbital period and its diameter. Moreover, EPOCh will have a serious edge over ground-based observatories, being able to watch each target for weeks at a time and working without an atmosphere that could distort received data. You can find a target list for EPOCh here. Thus far, observations of the giant planet HAT-P-4 seem to have been a particularly successful, with confirmed transits in the voluminous data awaiting further investigation.

I mentioned how tricky some of our acronyms can be, but how about star designations? In a recent newsletter covering the EPOCh work, Deming noted that HAT-P-4 is also known, depending on the database you use, as SAO 64638 and TYC 2569-1599-1. We’re dealing with an 11th magnitude G-class star located in the constellation Boötes. Of the 293 planets thus far found around other stars, 51 are known to be transiting.

Because such transits are detectable with properly configured amateur equipment, do be aware of TransitSearch, which works with observers worldwide to observe candidate stars when transits might occur. Interestingly, GJ 436, the EPOCh target discussed above, is in need of all the observations it can get, recent work suggesting the proposed second planet may not in fact exist. EPOCh should be able to tell us more, but interested amateurs can help by getting involved with TransitSearch.

Great post! I’m anxiously awaiting the results from EPOXI’s observations of GJ436, and also the “Earth-as-an-exoplanet” observations. Hopefully those will be released sometime this summer.

Everyone is paying attention to EPOXI’s potential for finding other Earth-like worlds, but I’m very glad to see you mention its potential to find moons of the known giant exoplanets too. It will be interesting to see whether EPOXI bags the first “exomoon,” particularly since so many moons in the outer solar system seem to be promising sites for life (Europa, Titan, Enceladus, etc.), and our own moon appears to have been crucial for the development of advanced life on Earth. Finding extrasolar moons may become increasingly vital in the search for life and intelligence in the future.

There’s already been a good bit of research into detecting moons of extrasolar planets, surprisingly. Just in the last week, two papers appeared on the arXiv discussing how they might be detected using microlensing or pulsar-timing searches — they both contain several references to earlier papers that discussed finding moons via transit searches.

Microlensing Detections of Moons of Exoplanets

http://xxx.lanl.gov/abs/0805.2642

Possibility of Detecting Moons of Pulsar Planets Through Time-of-Arrival Analysis

http://arxiv.org/abs/0805.4263

Fascinating topic, Lee. And to think how short a time it has been since we were without a single detected exoplanet! Now we’re talking about detecting exoplanetary moons and rings, and taking dead aim at that first terrestrial-size world. The next few years should be packed with interesting things, Kepler not the least of them.

Hi Guys

Nice how they managed to recycle a space-probe to do it all too. Deep Impact was a cool mission, and now it gets an extended life as EPOXI and as a comet-flyby. Cassini will similarly still be going strong after its official mission end in July – the current 2 year extension just doesn’t do the $3 billion invested in it justice. Personally I’d like to see it aerobraked into a radar-mapping orbit of Titan and do a “Magellan” style radar-mapping mission of the whole globe. I’m sure some nervous nellies wouldn’t want it potentially contaminating Titan’s putative ecosystem, but it seems like such a shame to leave so much of Titan as just fuzzy infra-red pictures. Higher definition fuzzy radar pictures would be a great legacy for such a major mission.

Periastron Precession Measurements in Transiting Extrasolar Planetary Systems at the Level of General Relativity

Authors: András Pál (1,2), Bence Kocsis (1,2) ((1) Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, (2) Eötvös Loránd University)

(Submitted on 4 Jun 2008)

Abstract: Transiting exoplanetary systems are surpassingly important among the planetary systems since they provide the widest spectrum of information for both the planet and the host star. If a transiting planet is on an eccentric orbit, the duration of transits T_D is sensitive to the orientation of the orbital ellipse relative to the line of sight. The precession of the orbit results in a systematic variation in both the duration of individual transit events and the observed period between successive transits, P_obs. The periastron of the ellipse slowly precesses due to general relativity and possibly the presence of other planets in the system. This secular precession can be detected through the long-term change in P_obs (transit timing variations, TTV) or in T_D (transit duration variations, TDV).

We estimate the corresponding precession measurement precision for repeated future observations of the known eccentric transiting exoplanetary systems (XO-3b, HD 147506b, GJ 436b and HD 17156b) using existing or planned space-borne instruments. The TDV measurement improves the precession detection sensitivity by orders of magnitude over the TTV measurement. We find that TDV measurements over a ~4 year period can typically detect the precession rate to a precision well exceeding the level predicted by general relativity.

Comments: Accepted for publication in MNRAS, 8+epsilon pages, 2 figures

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0806.0629v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Andras Pal Mr. [view email]

[v1] Wed, 4 Jun 2008 02:56:39 GMT (37kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0806.0629

Observability of the General Relativistic Precession of Periastra in Exoplanets

Authors: Andres Jordan, Gaspar A. Bakos

(Submitted on 3 Jun 2008)

Abstract: The general relativistic precession rate of periastra in close-in exoplanets can be orders of magnitude larger than the magnitude of the same effect for Mercury. The realization that some of the close-in exoplanets have significant eccentricities raises the possibility that this precession might be detectable.

We explore in this work the observability of the periastra precession using radial velocity and transit light curve observations. Our analysis is independent of the source of precession, which can also have significant contributions due to additional planets and tidal deformations.

We find that precession of the periastra of the magnitude expected from general relativity can be detectable in timescales of <~ 10 years with current observational capabilities by measuring the change in the primary transit duration or in the time difference between primary and secondary transits. Radial velocity curves alone would be able to detect this precession for super-massive, close-in exoplanets orbiting inactive stars if they have ~100 datapoints at each of two epochs separated by ~20 years. We show that the contribution to the precession by tidal deformations may dominate the total precession in cases where the relativistic precession is detectable. Studies of transit durations with Kepler might need to take into account effects arising from the general relativistic and tidal induced precession of periastra for systems containing close-in, eccentric exoplanets.

Such studies may be able to detect additional planets with masses comparable to that of Earth by detecting secular variations in the transit duration induced by the changing longitude of periastron.

Comments: 13 pages, 5 figures. Accepted for publication in ApJ

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0806.0630v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Andres Jordan [view email]

[v1] Tue, 3 Jun 2008 20:06:22 GMT (54kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0806.0630

Deep Impact view of Earth and the Moon

Deep Impact took this photo of Earth and the Moon together as a

part of its EPOXI extended mission, a search for extrasolar planets.

The color image was snapped from nearly 50 milion kilometers

(30 million miles) away on May 29, 2008 at 06:40 UTC, at a time

when the Moon was transiting Earth as seen from Deep Impact.

Credit: NASA / JPL / UMD / GSFC

http://planetary.org/image/Earth-Moon.png

Vanderbilt astronomers getting into planet-finding game

NASHVILLE, Tenn. Vanderbilt astronomers have constructed a special-purpose

telescope that will allow them to participate in one of the

hottest areas in astronomy the hunt for earthlike planets circling other

stars.

The instrument, called the Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope

(KELT), has been assembled and is being tested at Vanderbilt’s Dyer

Observatory. Shortly, it will be shipped to South Africa where it will

become only the second dedicated planet-finder scanning the stars in the

southern sky.

The KELT project is a collaboration between Vanderbilt and the

University of Cape Town. The instrument will be set up at the South African

Astronomical Observatory located about 200 miles northeast of the city of

Cape Town. The South Africans have built a special enclosure to hold the

telescope. They will maintain the instrument and ship the data that it

produces back to Nashville. The telescope is designed for remote operation

so it can be controlled by astronomers at both universities.

As its name implies, KELT is a very small telescope, about the

size of some of the telescopes used by amateur astronomers. Its optics are

surprisingly modest: It uses a professional quality photographic lens. But

it has an extremely high quality imaging system that captures the light and

converts it to digital data. It cost about $50,000 to construct.

“The telescope has been designed to detect planets passing

across the face of bright stars,”says Joshua Pepper, the post-doctoral

fellow who is managing the project. As a doctoral student at Ohio State

University, he worked on the problem of finding planets around distant stars

using large amounts of data. If a planet crosses the face of the star, it

blocks a small percentage of the sunlight. KELT is designed to detect these

subtle fluctuations in nearby stars similar to the sun. It is a copy of a

similar instrument that Pepper helped design for OSU that has been set up in

Arizona.

Unlike large telescopes that focus in on small parts of the sky

in order to produce extremely high resolution images, KELT looks at large

areas of the sky that contain thousands of stars. In order to see variations

in brightness, it must frequently revisit each area many times every night.

As a result, the small scope will produce prodigious amounts of data (enough

to fill a typical laptop’ hard drive in a few days). In order to pick out

the variations caused by planets from other effects, such as dimming caused

by passing clouds or variations in a star’ overall brightness, the

astronomers will process the data with the supercomputer in Vanderbilt’s

Advanced Computing Center for Research & Education.

According to Associate Professor of Astronomy Keivan Stassun,

KELT is an example of a new program called the Vanderbilt Initiative in

Data-Intensive Astrophysics (VIDA) [http://www.vanderbilt.edu/astro/vida].

“Astronomy is now entering a period when the way astronomers do their work

is fundamentally changing,” Stassun says. “The traditional model has been

that of an individual astronomer, or a small team of astronomers, going to a

telescope and pointing it at a star or a galaxy, collecting data, analyzing

the data and publishing the results. But, with the advent of

high-performance computers, robotic telescopes and digital detectors that

are able to see large swaths of the sky at once, the quantities of data that

we can collect are rapidly increasing so we need new ways of analyzing them

in real time.” The purpose of VIDA, which is funded by the Office of the

Provost, is to give Vanderbilt astronomers the resources they need to become

leaders in this new way of conducting astronomical research.

The agreement to place the new telescope in South Africa was the

result of a second campus initiative coming from the Vanderbilt

International Office. “We are in the process of identifying peer

institutions in all parts of the world with whom we can collaborate on

research projects in a variety of disciplines,” explains Joel Harrington,

assistant provost for international affairs.

The Cape Town agreement is one of four “International core

partnerships” that Vanderbilt has established. The other three are with the

University of Melbourne in Australia, The University in Sao Paulo in Brazil

and Fudan University in Shanghai, China.

In addition to collaborating on research projects, the

partnerships involve the exchange of students. Two Nashville students have

gone to Cape Town to study and two Cape Town students will come to

Nashville. A number of the Nashville exchange students will be drawn from

the Fisk-Vanderbilt Masters-to-PhD Program, a joint program with Fisk

University, Nashville’s historically black university.

“An important goal of the new research partnership is building

and enhancing the scientific capacity among black South Africans and African

Americans,” according to a media statement issued by the University of Cape

Town.

For more news about Vanderbilt, visit the Vanderbilt News Service homepage

on the Internet at http://www.vanderbilt.edu/News.

A Hubble Space Telescope transit light curve for GJ436b

Authors: J. L. Bean, G. F. Benedict, D. Charbonneau, D. Homeier, D. C. Taylor, B. McArthur, A. Seifahrt, S. Dreizler, A. Reiners

(Submitted on 4 Jun 2008)

Abstract: We present time series photometry for six partial transits of GJ436b obtained with the Fine Guidance Sensor instrument on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). Our analysis of these data yields independent estimates of the host star’s radius R_star = 0.505 +0.029/-0.020 R_sun, and the planet’s orbital period P = 2.643882 +0.000060/-0.000058 d, orbital inclination i = 85.80 +0.21/-0.25 deg, mean central transit time T_c = 2454455.279241 +0.00026/-0.00025 HJD, and radius R_p = 4.90 +0.45/-0.33 R_earth.

The radius we determine for the planet is larger than the previous findings from analyses of an infrared light curve obtained with the Spitzer Space Telescope. Although this discrepancy has a 92% formal significance (1.7 sigma), it might be indicative of systematic errors that still influence the analyses of even the highest-precision transit light curves.

Comparisons of all the measured radii to theoretical models suggest that GJ436b has a H/He envelope of ~10% by mass. We also find that the transit times for GJ436b are constant to within 10 s over the 12 planetary orbits that the HST data span. However, the ensemble of published values exhibits a long-term drift and our mean transit time is 128 s later than that expected from the Spitzer ephemeris.

The sparseness of the currently available data hinders distinguishing between an error in the orbital period or perturbations arising from an additional object in the system as the cause of the apparent trend. Assuming the drift is due to an error in the orbital period we obtain an improved estimate for it of P = 2.643904 +/- 0.000005 d. This value and our measured transit times will serve as important benchmarks in future studies of the GJ436 system. (abridged)

Comments: Accepted for publication in A&A

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0806.0851v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Jacob Bean [view email]

[v1] Wed, 4 Jun 2008 20:26:09 GMT (48kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0806.0851

Observational Consequences of the Recently Proposed Super-Earth Orbiting GJ436

Authors: Jacob L. Bean, Andreas Seifahrt

(Submitted on 19 Jun 2008)

Abstract: Ribas and collaborators have recently proposed that an additional, ~5 M_earth planet orbits the transiting planet host star GJ436. Long-term dynamical interactions between the two planets leading to eccentricity excitation might provide an explanation for the transiting planet’s unexpectedly large orbital eccentricity.

In this paper we examine whether the existence of such a second planet is supported by the available observational data when the short-term interactions that would result from its presence are accounted for. We find that the model for the system suggested by Ribas and collaborators lead to predictions that are strongly inconsistent with the measured host star radial velocities, transiting planet primary and secondary eclipse times, and transiting planet orbital inclinations.

A search for an alternative two planet model that is consistent with the data yields a number of plausible solutions, although no single one stands out as particularly unique by giving a significantly better fit to the data than the nominal single planet model.

We conclude from this study that Ribas and collaborator’s general hypothesis of an additional short-period planet in the GJ436 system is still plausible, but that there is not sufficient evidence to support their claim of a planet detection.

Comments: Accepted for publication in A&A Letters

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0806.3270v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Jacob Bean [view email]

[v1] Thu, 19 Jun 2008 20:40:40 GMT (31kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0806.3270

EPOCh’s first target and May’s observing challenge HAT-P-4, a magnitude 11, G-class star, is still visible in the evening sky in the constellation Boötes. Another of EPOCh’s targets observed by the project during May was GJ 436. At about 33 light-years, it is one of the closer targets to be observed by the EPOXI mission.

GJ436 = LHS 310 = HIP 57087 is a magnitude 10.7, M2.5-class star located in the constellation Leo. The reddish-colored star will be a challenge to observe only because it is in a part of the sky that will soon be obscured by the sun and therefore not viewable again until the early morning hours in late September.

Chart: http://epoxi.umd.edu/2science/challenge.shtml

The case for a close-in perturber to GJ 436 b

Authors: Ignasi Ribas (CSIC-IEEC, Spain), Andreu Font-Ribera (CSIC-IEEC, Spain), Jean-Philippe Beaulieu (IAP, France), Juan Carlos Morales (IEEC, Spain), Enrique Garcia-Melendo (OED, Spain)

(Submitted on 1 Jul 2008)

Abstract: The increasing number of transiting planets raises the possibility of finding changes in their transit time, duration and depth that could be indicative of further planets in the system. Experience from eclipsing binaries indeed shows that such changes may be expected.

A first obvious candidate to look for a perturbing planet is GJ 436, which hosts a hot transiting Neptune-mass planet in an eccentric orbit. Ribas et al. (2008) suggested that such eccentricity and a possible change in the orbital inclination might be due to a perturbing small planet in a close-in orbit. A radial velocity signal of a 5 M_earth planet close to the 2:1 mean-motion resonance seemed to provide the perfect candidate. Recent new radial velocities have deemed such signal spurious.

Here we put all the available information in context and we evaluate the possibility of a small perturber to GJ 436 b to explain its eccentricity and possible inclination change. In particular, we discuss the constraints provided by the transit time variation data.

We conclude that, given the current data, the close-in perturber scenario still offers a plausible explanation to the observed orbital and physical properties of GJ 436 b.

Comments: 7 pages, 3 figures, to appear in the proceedings of IAU Symposium 253 on Transiting Planets

Subjects: Astrophysics (astro-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0807.0235v1 [astro-ph]

Submission history

From: Ignasi Ribas [view email]

[v1] Tue, 1 Jul 2008 20:19:01 GMT (817kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0807.0235

A Search for Additional Planets in the NASA EPOXI Observations of the Exoplanet System GJ 436

Authors: Sarah Ballard, Jessie L. Christiansen, David Charbonneau, Drake Deming, Matthew J. Holman, Daniel Fabrycky, Michael F. A’Hearn, Dennis D. Wellnitz, Richard K. Barry, Marc J. Kuchner, Timothy A. Livengood, Tilak Hewagama, Jessica M. Sunshine, Don L. Hampton, Carey M. Lisse, Sara Seager, Joseph F. Veverka

(Submitted on 15 Sep 2009)

Abstract: We present time series photometry of the M dwarf transiting exoplanet system GJ 436 obtained with the the EPOCh (Extrasolar Planet Observation and Characterization) component of the NASA EPOXI mission.

We conduct a search of the high-precision time series for additional planets around GJ 436, which could be revealed either directly through their photometric transits, or indirectly through the variations these second planets induce on the transits of the previously known planet.

In the case of GJ 436, the presence of a second planet is perhaps indicated by the residual orbital eccentricity of the known hot Neptune companion. We find no candidate transits with significance higher than our detection limit. From Monte Carlo tests of the time series, we rule out transiting planets larger than 1.0 R_Earth interior to GJ 436b with 95% confidence. Assuming coplanarity of additional planets with the orbit of GJ 436b, we cannot expect that putative planets with orbital periods longer than about 3.4 days will transit.

However, if such a planet were to transit, we rule out planets larger than 1.5 R_Earth with orbital periods less than 13 days with 95% confidence. We also place dynamical constraints on additional bodies in the GJ 436 system. Our analysis should serve as a useful guide for similar analyses for which radial velocity measurements are not available, such as those discovered by the Kepler mission.

These dynamical constraints on additional planets with periods from 0.5 to 9 days rule out coplanar secular perturbers as small as 10 M_Earth and non-coplanar secular perturbers as small as 1 M_Earth in orbits close in to GJ 436b.

We present refined estimates of the system parameters for GJ 436. We also report a sinusoidal modulation in the GJ 436 light curve that we attribute to star spots. [Abridged]

Comments: 28 pages, 8 figures, 3 tables, submitted to ApJ

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:0909.2875v1 [astro-ph.EP]

Submission history

From: Sarah Ballard [view email]

[v1] Tue, 15 Sep 2009 20:19:32 GMT (597kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.2875